I end 2012 with two posts related to my beloved Silicon Valley. This one is about the two great Venture Capital firms Sequoia Capital and Kleiner, Perkins, Caufield and Byers. The next one will be about Palo Alto-based author of thrillers, Keith Raffel.

I have already said a lot about these two firms. You can for example read again the following on KP:

– About KP first fund (3 posts)

– Tom Perkins, a Silicon Valley venture capitalist

– Robert Swanson, 1947-1999

and about Sequoia:

– When Valentine was talking (2 posts)

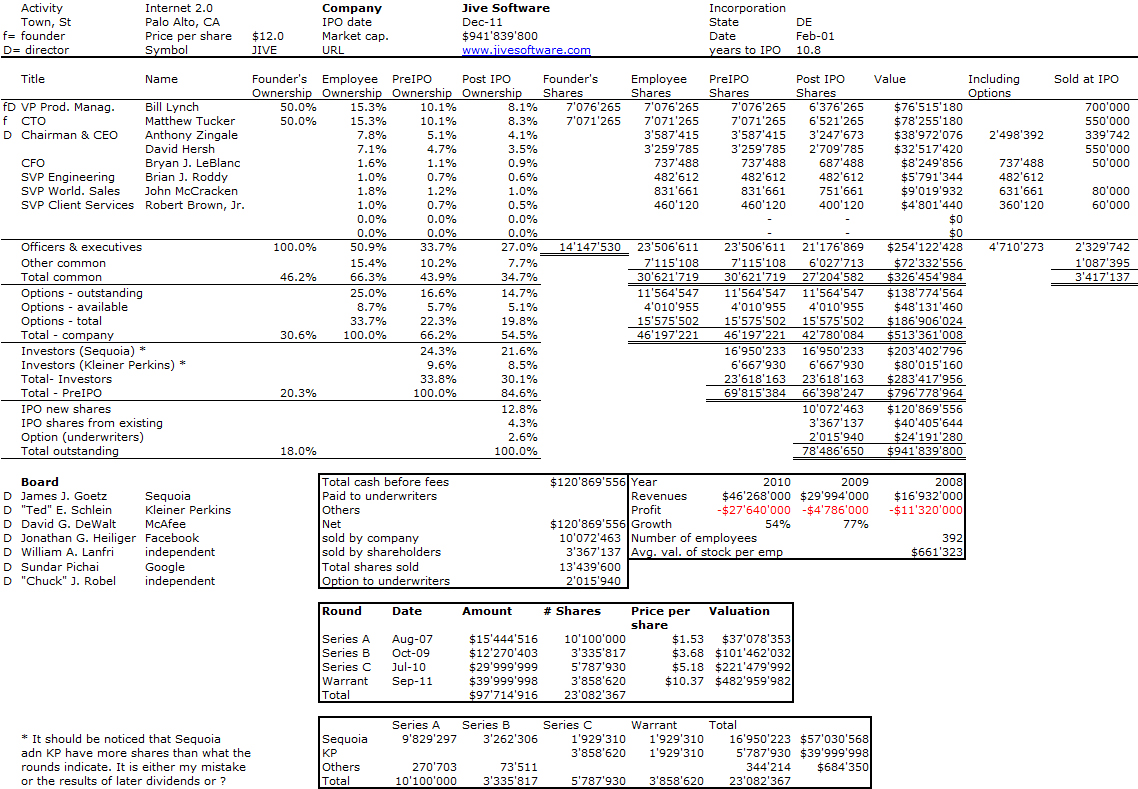

The recent IPO of Jive is the motivation for this new post because Jive has both funds as co-investors. I am obviously providing my now-usual cap. table and what you can discover here is the huge amounts of money both funds have poured in the start-up ($57M for Sequoia and $40M for KP) … is this still venture capital? I am not sure.

I am not writing an article on Jive here but let me add that we have again here two founders who had each 50% of the start-up at creation and end up with 8%, the investors have 30%. What is really unusual is that the company raised money in 2007, six years after inception. A sign of a new trend in high-tech?

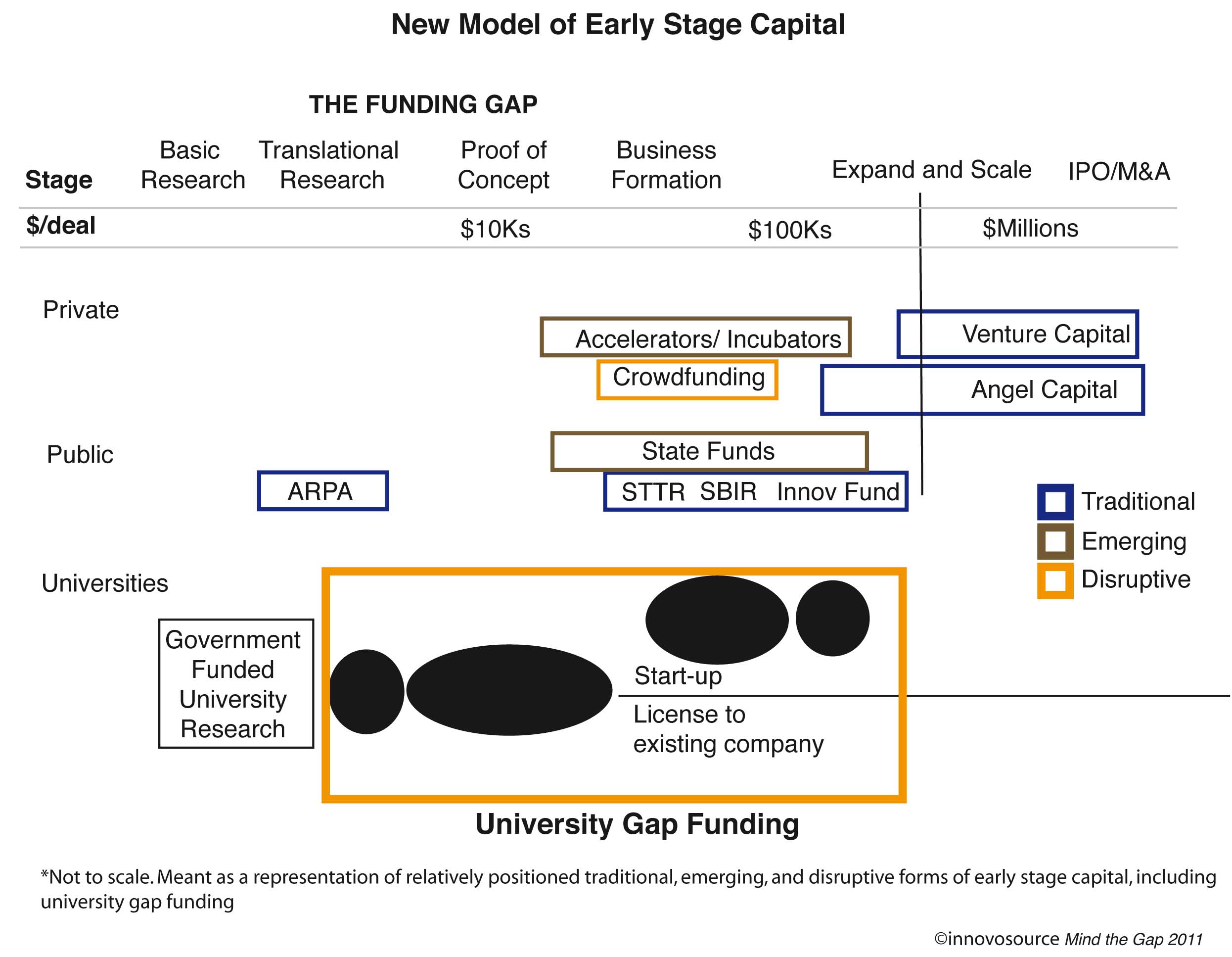

Now back to Sequoia and KP. When they co-invested in Google in 1999, I thought it had been a very unusual event. David Vise in his Google Story (pages 66-68; I also have mine!) explains how the start-up founders desired to have both funds to “divide and conquer”, hoping no single fund would control them. When I met Pierre Lamond, then at Sequoia, in 2006, I was surprised to learn from him that in fact the two funds has regularly co-invested together. As often in Silicon Valley, it is about co-opetition, not just competition.

So I did my short analysis. A first Internet search got me the following:

– The question on Quora “How unusual is it for both Kleiner Perkins and Sequoia to co-invest in a company?” (August 2010) gives 11 recent investments, including Jive and Google.

– Russ Garland in the Wall Street Journal adresses the topic in “Kleiner Perkins, Sequoia Combo Has Solid Track Record” (July 2010). He says: “But the two Menlo Park, Calif.-based firms have done plenty of other deals together – at least 53, according to VentureWire records. It’s been a fruitful relationship: 29 of them have gone public. They include Cypress Semiconductor Corp., Electronic Arts Inc., Flextronics International and Symantec Corp. That track record lends credibility to the excitement generated by the Jive investment. But most of those 53 deals were done prior to 2000; the two firms have been less collaborative since then. Of the handful of companies that both Kleiner Perkins and Sequoia have backed since 2000, at least one is out of business. That would be Abeona Networks, a developer of technology for Internet-based services.”

– Now in my own Equity List, I have 4 (Tandem, Cypress, EA, google) plus Jive.

So I did a more systematic analysis and found 55 companies. More than the WSJ! I will not put the full list here, but let me give more data: Kleiner has invested a total of $267M whereas Sequoia put $268M [this is strangely similar!], i.e. about $5M per start-up. On average, KP invested in round #2.07 and Sequoia in round #2.63, so a little later. Time to exit from foundation is 6.5 years. I found 27 IPOs (I miss two compared to the WSJ)

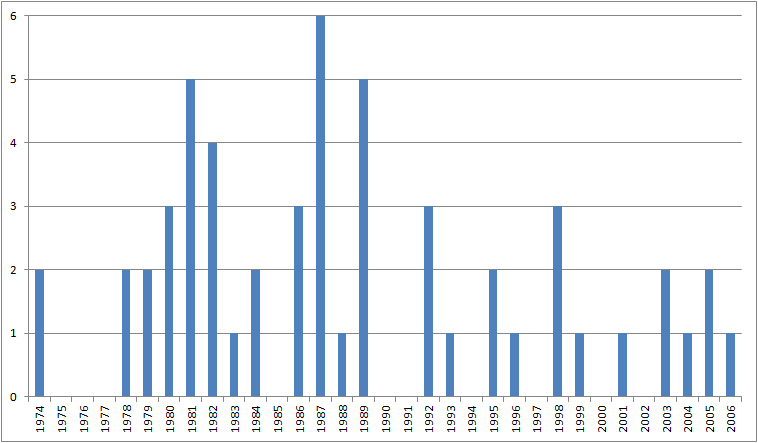

Is Garland right when he claims “But most of those 53 deals were done prior to 2000; the two firms have been less collaborative since then”? Here is my analysis:

Number of co-investments related to the start-up foundation year

If I look at the decades, it gives,

70s: 6,

80s: 30,

90s: 11,

00s: 7.

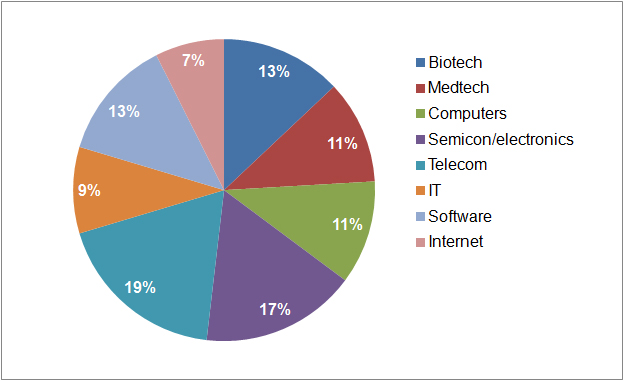

Clearly KP and Sequoia co-invested a lot in the 80s, much less in the 90s and 00s. Whereas the fields are

So what? I am not sure 🙂 . KP and Sequoia are clearly two impressive funds and as a conclusion, I’d like to thank Fredrik who pointed me to Business Week’s The Venture Capital Winners of 2011.

Sequoia and KP may not be #1 and #2, but their track record remains more than impressive. Here is a bad picture taken on an iPad!