– Part 1 covers the Innovation dilemmas and crises.

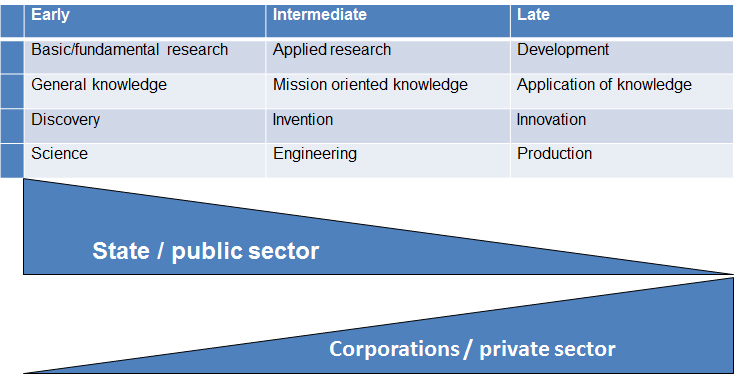

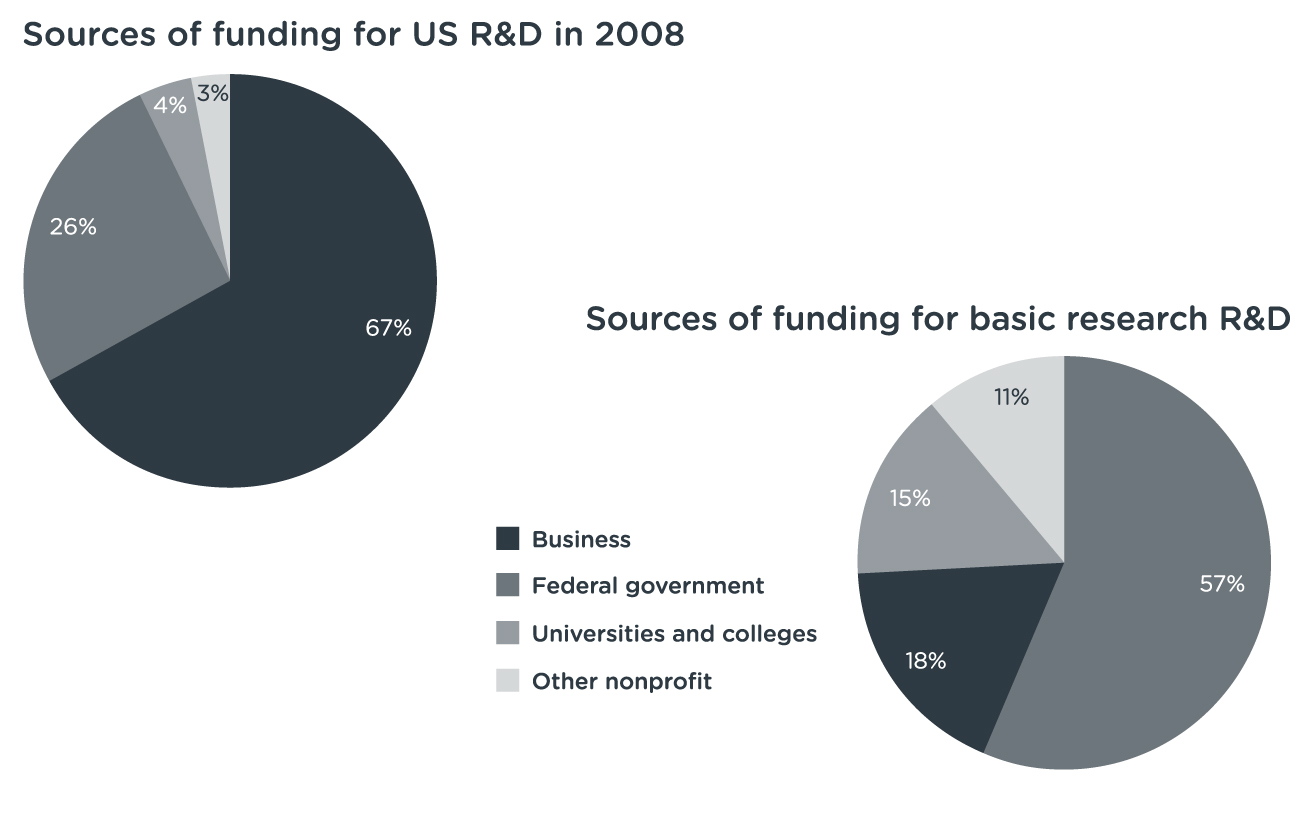

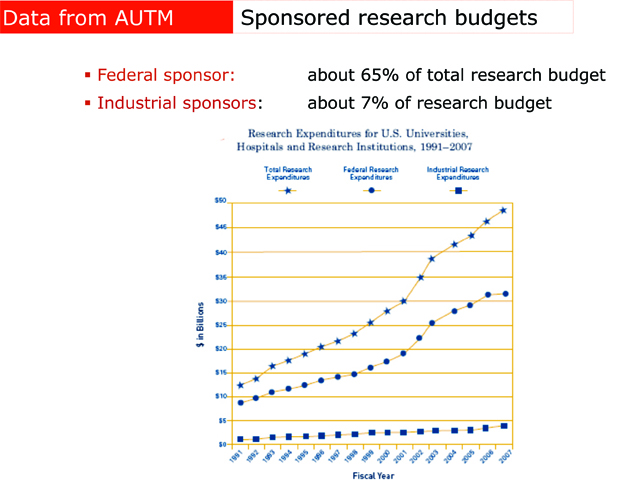

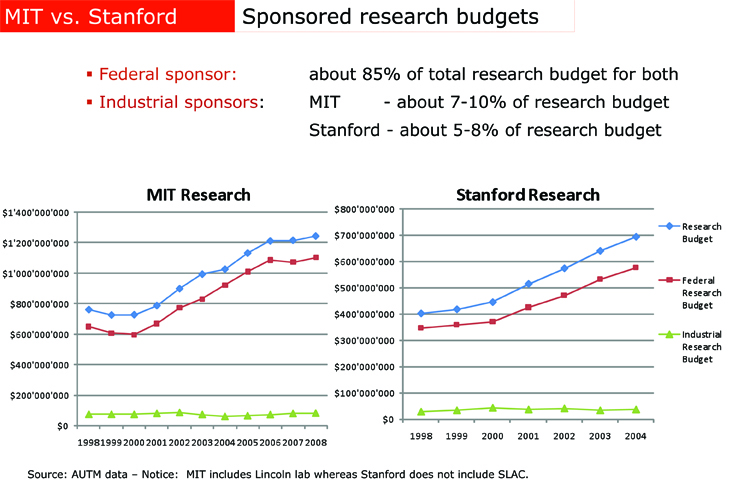

– Part 2 deals with the (forgotten or untold) role of the state in stimulating innovation through research.

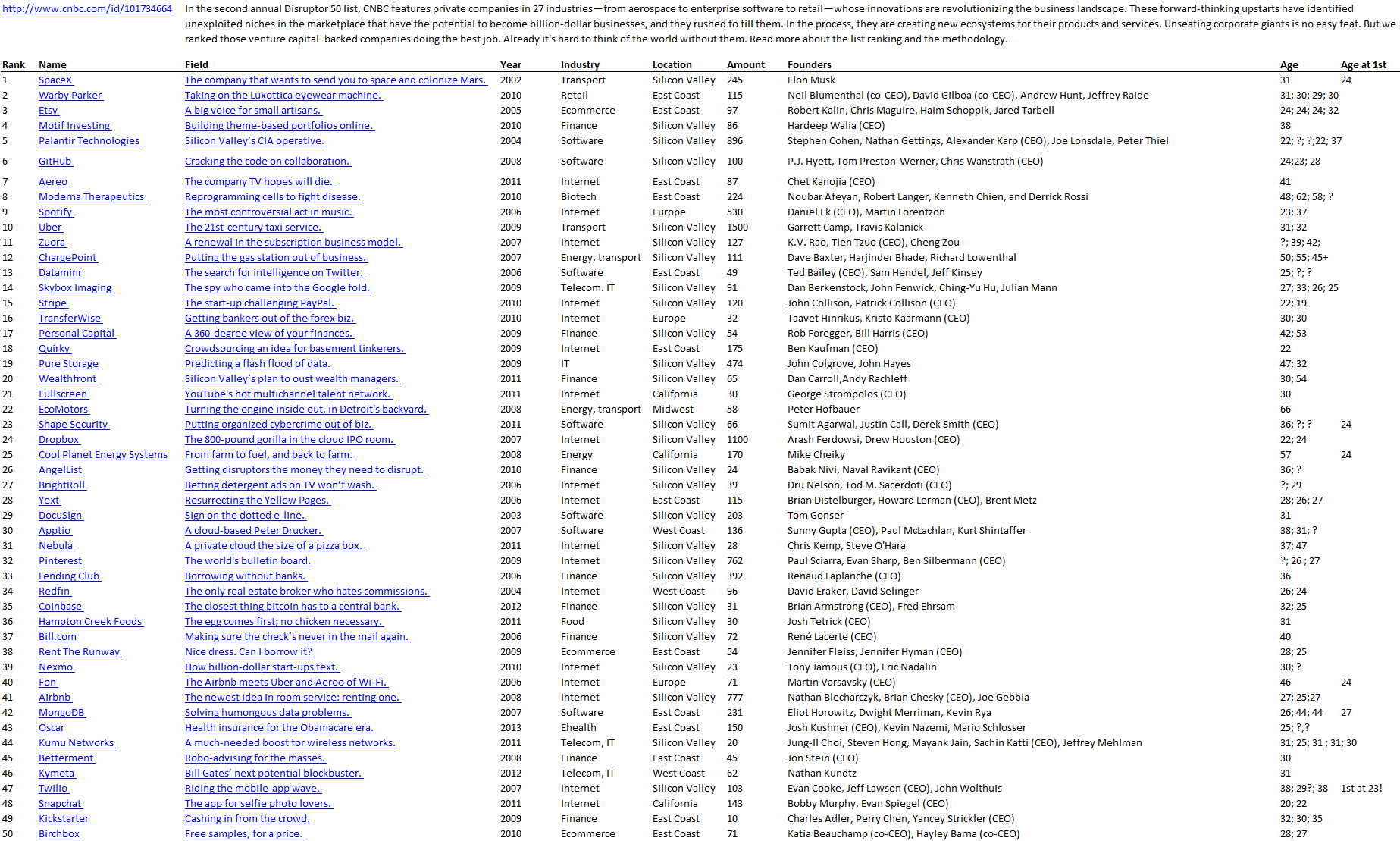

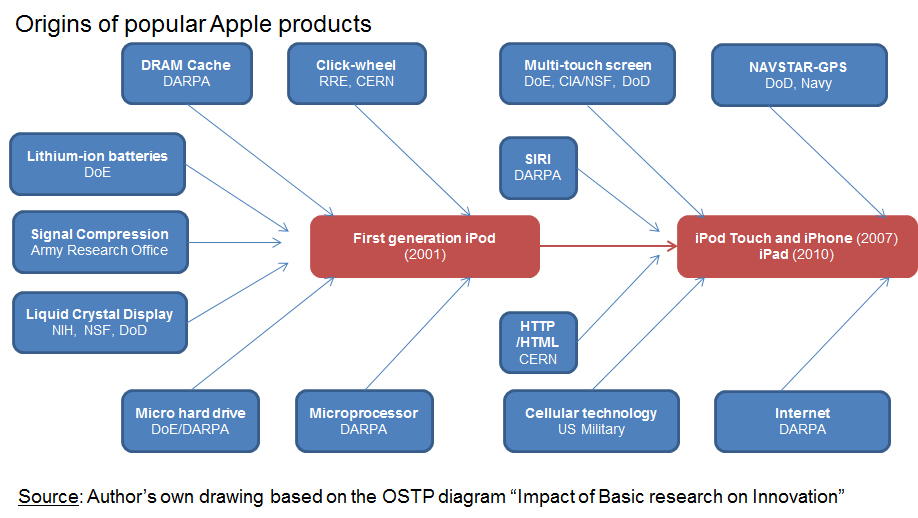

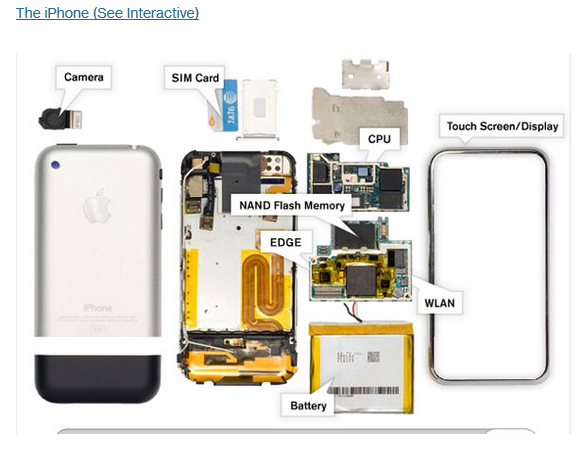

– Part 3 is about the role of the State in the iPhone technologies.

Now chapters 6 to 8:

Chapter 6 – Pushing vs. Nudging the Green Industrial Revolution.

The Green technology is another very interesting situation. “Until wind turbines and solar PV panels can produce energy at a cost equal to or lower than those of fossil fuels, they will likely continue to be marginal technologies that cannot accelerate the transition so badly needed to mitigate climate change.” [Page 114] “Demand-side policies (regulations) are critical but they too often become pleas for change. Supply side policies (energy generation) are important for putting the money were the mouth is.” [Page 155]

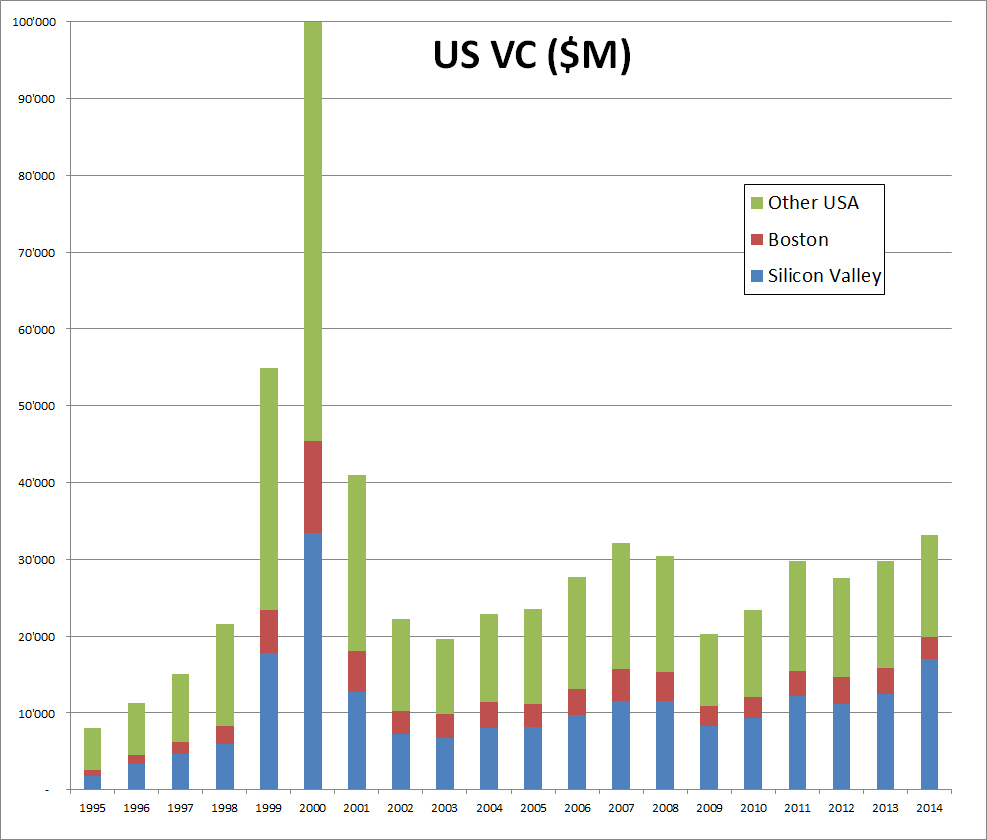

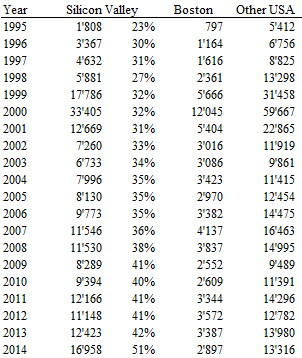

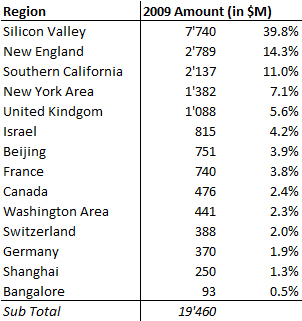

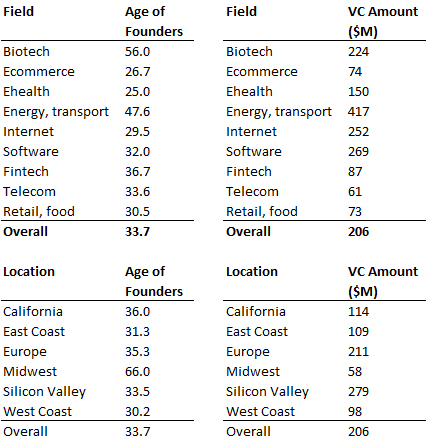

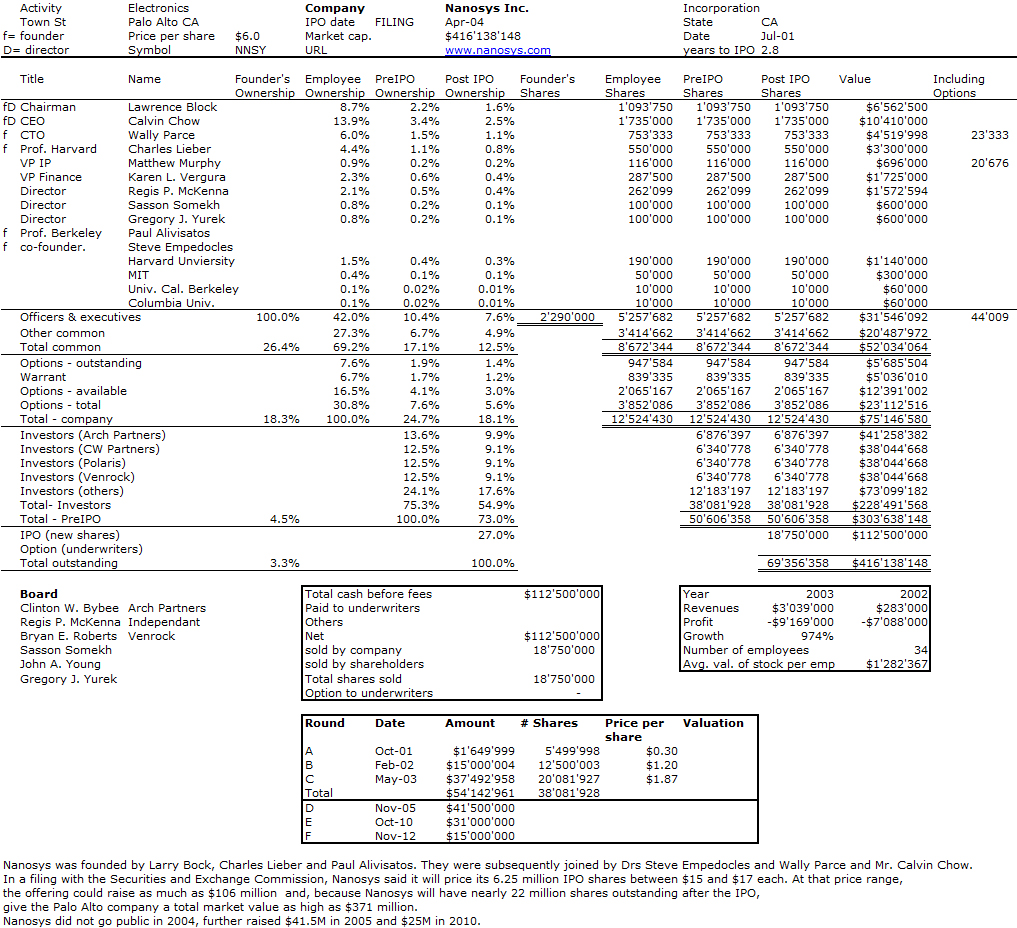

Again I have been a cautious observer of green technologies with Germany subsidizing many companies which went bankrupt when China arrived with much cheaper products, with France or Japan claiming nuclear energy as the cleanest… Mazzucato rightly describes “the US with a fund-everything approach, hoping that a breakthrough disruptive energy innovation will sooner or later emerge. This has not been the case because many clean technologies require long-term financial commitment of a kind VCs are not willing or able to undertake”. In my ongoing analysis of recent IPO filings, I noticed 11 companies in green technologies out of the 165 filings I have built since 2002. The oldest one was filed in 2009. These companies had raised more than $2B or about $180M per company. They had more than 5’000 employees in total. It looked to me like a speculative bubble so Mazzucato is right when saying investors are impatient. I am not sure they are shy with their money though.

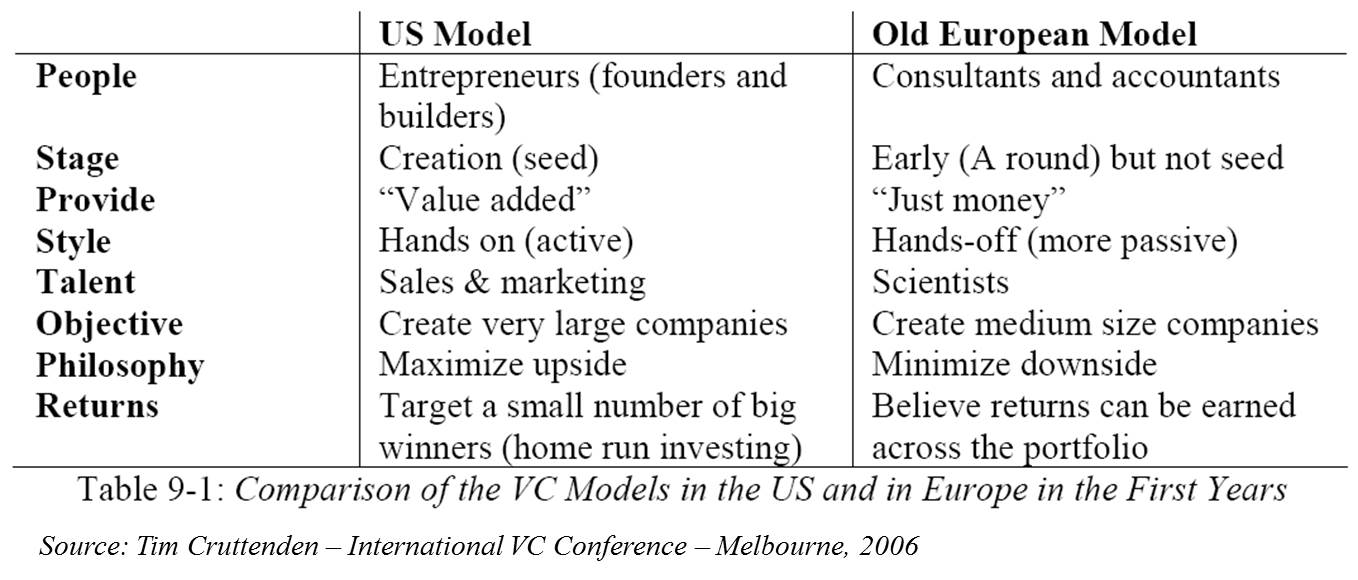

The US has been busy building on their understanding of what has worked in previous technological revolutions. (…) But while it has been good at connecting and leveraging academia, industry and entrepreneurship in its own push into clean technology, its performance has been uneven. (…) A key reason for uneven US performance has been its heavy reliance on venture capital to “nudge” the development of green technologies. (…) Since some clean technologies are still in early stages, when “Knightian uncertainty” is highest, VC funding is focused on some of the safer bets rather than on the radical innovation that is required to allow the sector to transform society. (Pages 126-127) The conclusion that might follow is that the government should focus exclusively on commissioning the development of the riskiest technologies.

Impatient capital can destroy firms promising to deliver government-financed technology. If VCs aren’t interested in capital-intensive industries, or in building factories, what exactly are they offering in terms of economic development? Their role should be seen for what it is: limited. (Page 131)

The expectation is that the opportunity to conduct high-risk and path-breaking research “will attract many of the US’s best and brightest minds – those of experienced scientists and engineers and especially those of students and young researchers, including persons in the entrepreneurial world.” (Page 134)

The history of US government investment in innovation, from the Internet to nanotech, shows that it has been critical for the government to have a hand in both basic and applied research. NIH is responsible for 75 percent of the most radical new drugs. So the assumption one can leave applied research to the business sector and that this will spur innovation is one with little evidence to support it (and may even deprive some countries of important breakthroughs.) (Page 136)

In reality government and business activities frequently overlap. Venture capitalists and entrepreneurs respond to government support in choosing technologies to invest in, but are rarely focused on the long term. In the absence of an appropriate investment model, VC will struggle to provide the “patient capital” required for the full development of radical innovations. It is crucial that finance be patient. (Page 138)

Public finance (such as provided by State development banks) is therefore superior to VC or commercial banking in fostering innovation, because it is committed and patient.

The financial and technological risks of developing modern renewable energy have been too high for VC to support. A key problem is that VCs are looking for returns that are not realistic with capital-intensive technologies. The speculative returns possible in ICT revolutions are not a “norm” to be replicated in all other high-tech industries. (Page 140)

My comments: I agree with the criticism on venture capital. Now the solution introduced of committed and patient development banks is new to me. I understand “patient”, I am less sure about “committed”. Does this mean hands-on, and competent?

But my main concern is again about the difference between inventing and innovating. I need to go back to Apple. According to Wikipedia, a classical definition of Entrepreneurship is “the pursuit of opportunity without regard to resources currently controlled”. The term puts emphasis on the risk and effort taken by individuals who both own and manage a business, and on the innovations resulting from their pursuit of economic success.

When Mazzucato describes the Entrepreneurial State, she describes as much an Inventing State as an Innovating State. There is nothing wrong with it. What Apple has been strong at is using inventions and mostly innovations to integrate them in new products. It is why Apple is doing so little R&D. Can the same company do research and explore new green fields and develop new technologies into new products. I am not sure this has been shown by clear evidence. But we should probably ask historians of technology.

There is one invention that shows how difficult the transfer from invention to innovation might be: the transistor was invented at Bell Labs in 1947. Some of the elements of the invention only were patented (as they had been prior art back in 1925.) By 1951 Bell Labs had licensed (under the government pressure) the technology to more than 40 companies and (then small firms) Texas Instruments and Sony are known for producing early commercial transistors. The inventors received the Nobel Prize in 1957 and one of them moved to Palo Alto and is probably at the origin of Silicon Valley because of his decision. Because of the threat of USSR as an emerging technology power, the US poured a lot of military and space money on the potential of the electronics of the transistor.

The difficulty with nanotechnologies and green technologies is that in the chicken and egg of pull and push, the market needs may be clear, but the technology push looks to me much less so. I am not sure to see where the equivalent of the transistor is for these “promising” fields.

Chapter 7 – Wind and Solar power

This chapter is about the history and current status of these two energies. Wind power players are GE and Vestra from Denmark. There is a long and interesting history. There is a similar long and painful history for solar power. First Solar, Solyndra, SunPower, Evergreen are described in details. Mazzacutto focuses on China’s long-term strategy vs. the more US short term one, as well as Germany’s innovative approach to the market. “Solyndra’s failure highlights the “parasitic” innovation system that the US has created for itself – where financial interests are always and everywhere the judge, jury and executioner of all innovations investment dilemmas.” “Clean technology is already teaching us that changing the world requires coordination and the investment of multiple States, otherwise R&D, support for manufacturing, and support for market creation and function will remain dead ends.” (Page 155)

A framework would include demand-side policies to promote increased consumption as well as supply-side policies that promote manufacture of the technologies with patient capital. (Page 159)

But McKay’s arguments on Sustainable energy – without the hot air makes me cautious…

Mazzacuto still reminds of us of some fundamental elements: coming back on Myth 2 (small is beautiful) “We should not underestimate the role of small firms nor assume that only big firms have the right resources at their disposal. (…) The willingness to disrupt existing market models is needed in order to manifest a real green industrial revolution. (…) It should be a subject of debate whether public support should be handed-off to large firms that could have made their own investments and it is also unclear how they would be willing to shift from the technologies which provide their major sources of revenues.“ As my friend Dominique (:- rightly mentioned as a reaction to a previous post on the topic: “Research funding and how early the research is funded by a company of course depends on its expectations but also on its margins. Back in the seventies large corporations could afford to fund early research because 1) they foresaw stable or growing markets and 2) because their margins were constantly high I believe. Today the speed @ which markets evolve is certainly a deterrent to early stage research by companies…”

Chapter 8 – Risks and rewards: from Rotten Apples to Symbiotic Ecosystems.

Risk taking has been a collective endeavor while the returns have been much less collectively distributed. [Page 165]

The story US taxpayers are told is that economic growth and innovation are outcomes of individual “genius”, Silicon Valley “entrepreneurs”, venture capitalists or “small businesses”, provided regulations are lax (or nonexistent) and taxes low – especially compared to the “Big State” behind much of Europe. [Page 166]

The real Knightian uncertainty that innovation entails, as well as the inevitable sunk costs and capital intensity that it requires, is in fact the reason that the private sector, including venture capital, often shies away from it. It is also the reason why the State is the stakeholder that so often takes the lead, not only to fix markets, but to create them. [Page 167]

Keeping that story untold has allowed Apple to avoid “paying back” share of its profits to the same State. Apple incrementally incorporated in each new generation of products technologies that the state sowed, cultivated and ripened. [Page 168]

Mazzucato has then a very interesting analysis of Old and New Economy Business Model with Old being about stability, generosity, equity and New about volatility, mobility, and low commitments. Jobs are not equal even at Apple, from R&D where products are designed, to China where they are produced, or back to the USA where they are sold by Apple-owned stores; but worse the mobility and globalization has enabled tax evasion and optimization. Apple has a subsidiary in Nevada, Braeburn Capital to avoid income or capital gain taxes. Then is has subsidiaries in Luxembourg, Ireland, the Netherlands and British Virgin Islands for low-tax advantages. Apple IP is owned by Irish subsidiaries, which receive royalties on Apple sales (!) and which ownership is co-owned by another Virgin Islands subsidiary, Baldwin Holdings… GE, Google, Oracle, Amazon and Intel are also famous for tax optimization and tax loss could be $60-80B for the US over a decade. [pages 168-175]

The ultimate purpose of putting tax dollars to use for the development of new technologies is to take on the risk that normally accompanies the pursuit of innovative complex products and systems required to achieve collective goals. [Page 176]

Mazzucato terminates this new chapter with “Where are Today’s Bell Labs?” “One of the reasons unveiled in a [recent MIT] study is the fact that large R&D centers – like bell Labs, Xerox PARC and Alcoa Research Lab – have become a thing of the past in big corporations. Long-term basic and applied research is not part of the strategy of Big Business anymore. What is not clear however is why and how this has changed over time. The wedge between private and social returns (arising from the spillovers of R&D) was just as true in the era of bell Labs as they are today. And what is missing most today is the private component of R&D working in real partnership with the public component, creating what I call later a less symbiotic ecosystem. It is crucial to understand not only how to build an effective innovation “ecosystem”, but also and perhaps especially, how to transform that ecosystem so that it is symbiotic rather than parasitic. [Page 179]

On one side, I see the success of former emerging countries such as Taiwan and Korea, but I was also in the country of the Concorde, TGV, Rafale and Nuclear Power Plants that France has been struggling in selling abroad.

And why is Tesla and Elon Musk such an (early) success if not money is available for disruptive green technologies…

Similarly why was (military and civil) nuclear fission such a success whereas civil nuclear fusion has not given any commercial output 50 years after the military use? I remember reading Richard Feynman about the Manhattan Project and the crazy (entrepreneurial) intensity of the project. Would entrepreneurship be missing at ITER? Innovation and entrepreneurship are very much related and still somehow a mystery.

Planned innovation is a very difficult challenge that Mazzucato is not pushing for and uncertainty remains. Just remember how artificial intelligence has been a disappointment for many decades not to say until now. I’d like to finish here with an interesting article form Newspaper Le Monde:

Innovation is not about planning.

LE MONDE | 30.09.2013 | By Armand Hatchuel.

On September 12, the French, Francois Hollande, and the Minister of productive recovery, Arnaud Montebourg, presented thirty-four “plans for reconquest” from “thermal renovation of buildings” to “the factory of the future” through the “airships for heavy loads”. This announcement was seen as the return of industrial policy planning, and aroused the usual criticism of public voluntarism.

The criticism is questionable because, in this case, it is not really about planning. The themes are primarily intended to stimulate innovation and new industries. However, numerous studies have shown that innovation policy – whether public or private – can only succeed if its design, control and evaluation is clearly away from a logic of planning (Philippe Lefebvre, researcher at the Ecole Nationale Superieure des Mines de Paris : ” Organizing deliberate innovation in knowledge clusters : from accidental to purposeful brokering brokering processes” [Organiser l’innovation dans les écosystèmes : au-delà de l’émergence accidentelle, un pilotage des interactions créatrices], International Journal of Technology Management , Vol. 63 , No. 3/4, 2013).

A LARGE PART OF UNCERTAINTY

For what is a “plan”? In order to guide future action, one builds representations. We “plan” our vacation, which route to take and the loss of a few pounds. Still, while conceding uncertainties, a plan assumes that the goal, the means and the partners are sufficiently known. We may, at the limit, think that the means and partners will be selected “along the way”. But we must at least specify the goal. Agricultural policy, telecommunications policy and housing policy are built as plans which aim is clearly displayed: for example, a quantified production or equipment amount at a national level.

This is not the case anymore for a genuine innovation agenda. One must admit that the purpose is necessarily largely unknown. It is not possible anymore to specify in advance the paths and the most interesting results of the project.

Paradoxically, this does not prevent an innovative concept from mobilizing resources. Who would want a car “consuming less than two liters per 100 km”? But we must recognize that we do not know how this value will be transformed to in effecient technologies and products: will these be small city cars? Intelligent control systems? New types of vehicles and fuels? And we ignore if new businesses or new markets will emerge in the adventure.

History confirms thoroughly the surprising rationality of major innovation programs . In 1854, Austria launched the Semmering Pass competition for the design of the first locomotive for mountains. Many solutions were proposed, but none could succeed. However, the major beneficiaries of the innovations were Semmering … new locomotives in the plains!

OPENING NEW PATHS

Closer to us, neither Toyota nor Apple have ever launched projects to produce the Prius or iPhone. Their success came from their ability to pilot open innovation programs (” green car”, man-machine “magic” interfaces) and take advantage, before their competitors, of the disappointments or discoveries encountered. It is important to open very contrasting paths and pay attention to the crossings and learning that each causes.

For uncertainty does not paralyze action: it prevents its management according to the rigid codes of planning. In recent years, research has clarified the cognitive and collective mechanisms that restrict or enhance the exploration of the unknown. One better understands the control rules adapted to innovation, whether innovative design approaches (expansion of alternatives, conceptual hybridizations, exploration prototyping…) or the management of the various values that emerge (new skills, new markets, new usages…). In this respect, classical rationality is often misleading.

In the logic of the plan, there is the project distinct from its “benefits”. The success of the project is the goal, the benefits being recorded afterwards. This distinction does no longer exist in an innovation program. A “benefit” may be more important than the project itself. Driving innovation is to be prepared for the changing identity of the project and actively cause unexpected “impact”. The indeterminacy between “project” and “benefits” multiplies the sources of value and minimizes financial risks.

Beyond the economic rationality that is optimized in the known world, the rationality of innovation is reflected in the ability of project managers to regenerate solutions, markets and partnerships.

Faced with the challenge of industrial revival, the question is not whether the State should use planning. It is especially important to ensure that major projects launched will be conducted by the State and its industrial partners in the most rigorous approaches and more consistent with the expected intensity of innovation .

Harmand Hatchuel is a professor at Mines ParisTech