“Our technocratic elite told us to expect an ever-wealthier future, and science hasn’t. Except for computers and the Internet, the idea that we’re experiencing rapid technological progress is a myth.”

So speaks Peter Thiel in an interview to the Wall Street Journal Technology = Salvation that I read while traveling to Helsinki to discover the Finnish high-tech ecosystem (I will come back on my trip when I am back home). I did not know Peter Thiel was German, I mean one more European migrant to Silicon Valley. For those who do not know him, Thiel was the business angel in Paypal and then Facebook.

Zina Saunders

“People don’t want to believe that technology is broken. . . . Pharmaceuticals, robotics, artificial intelligence, nanotechnology—all these areas where the progress has been a lot more limited than people think. And the question is why.” […] Innovation, he says, comes from a “frontier” culture, a culture of “exceptionalism,” where “people expect to do exceptional things”—in our world, still an almost uniquely American characteristic, and one we’re losing. […] The idea that technology is broken is taboo. Really taboo.

Peter Thiel is an interesting fellow. A unique character, I am not sure he is a conservative or a libertarian like T. J. Rodgers. You should read the full article (I am not sure the WSJ still offers it for free, but I copied it below) as well as the comments. The reason why I mention this is that it is also a concern of mine I have wrote about in my previous posts on the crisis or about books on the science crisis such as Smolin, or (in French) Zuppiroli or Ségalat

So here is the full interview but I am not sure the WSJ would like this…

Technology = Salvation

An early investor in Facebook and the founder of Clarium Capital on the subprime crisis and why American ingenuity has hit a dead end.

By HOLMAN W. JENKINS JR.

The housing bubble blew up so catastrophically because science and technology let us down. It blew up because our technocratic elite told us to expect an ever-wealthier future, and science hasn’t delivered. Except for computers and the Internet, the idea that we’re experiencing rapid technological progress is a myth.

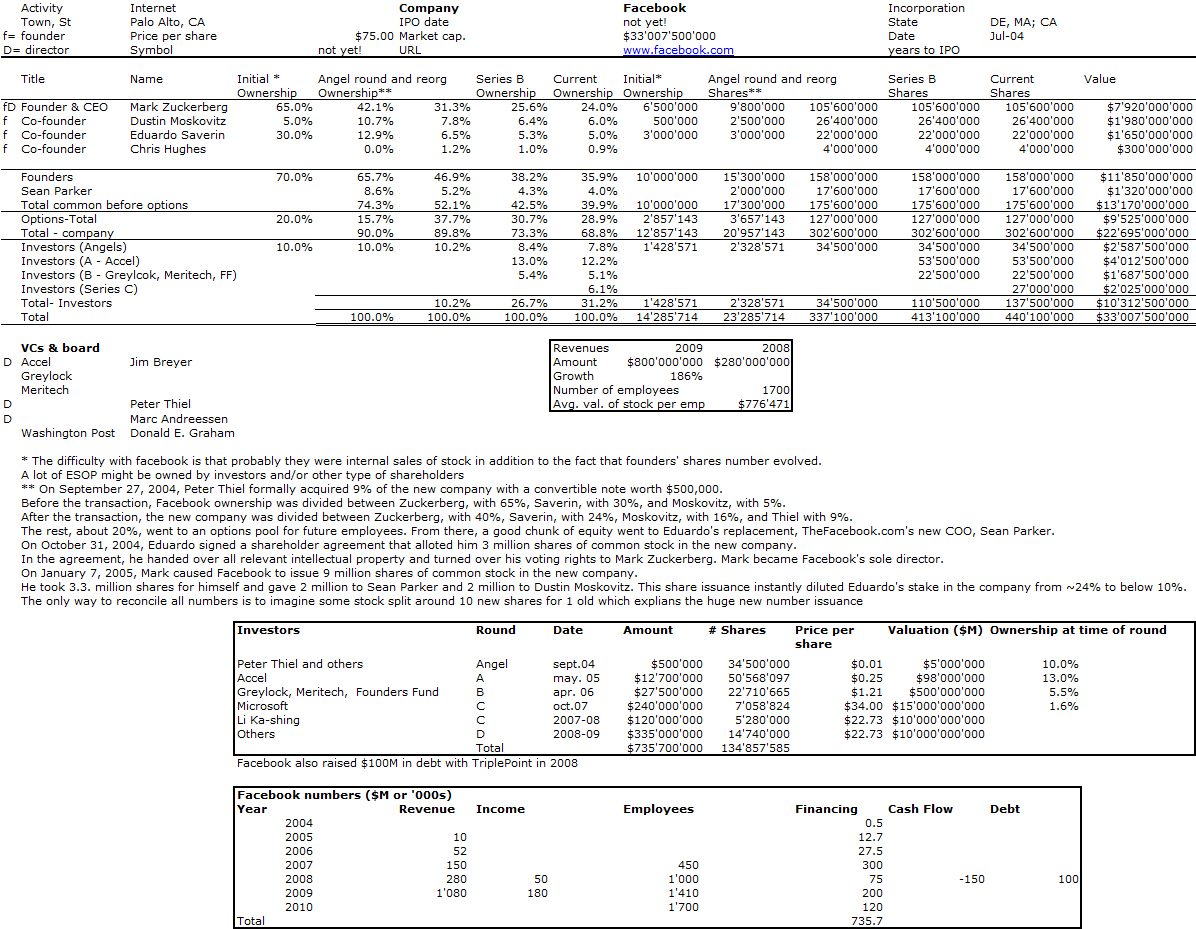

Such is the claim of Peter Thiel, who has either blundered into enough money that his crackpot ideas are taken seriously, or who is actually on to something. A cofounder of PayPal and an early investor in Facebook (his stake was recently reported to be around 3%), Mr. Thiel is the unofficial leader of a group known as the “PayPal mafia,” perhaps the most fecund informal network of entrepreneurs in the world, behind companies as diverse as Tesla (electric cars) and YouTube.

Mr. Thiel, whose family moved from Germany when he was a toddler, studied at Stanford and became a securities lawyer. After PayPal, he imparted a second twist to his career by launching a global macro hedge fund, Clarium Capital. He now matches wits with some of the great macro investors, such as George Soros and Stanley Druckenmiller, by betting on the direction of world markets.

Those two realms of investing—narrow technology and broad macro—are behind his singular diagnosis of our economic crisis. “All sorts of things are possible in a world where you have massive progress in technology and related gains in productivity,” he says. “In a world where wealth is growing, you can get away with printing money. Doubling the debt over the next 20 years is not a problem.”

“This is where [today is] very different from the 1930s. In the ’30s, the Keynesian stuff worked at least in the sense that you could print money without inflation because there was all this productivity growth happening. That’s not going to work today.

“The people who bought subprime houses in Miami were betting on technological progress. They were betting on energy prices coming down and living standards going up.” They were betting, in short, on the productivity gains to make our debts affordable.

We’ll get back to what all this means. Mr. Thiel wants to meet me at a noisy coffee shop near Union Square in Manhattan. Because a Fortune writer invited to his condo wrote about his butler? “No,” Mr. Thiel tells me. “And I don’t have a “butler.”

His mundane thoughts these days include whether Facebook should go public. Answer: Not anytime soon.

As a general principle, he says, “It’s somewhat dangerous to be a public company that’s succeeding in a context where other things aren’t.”

On the specific question of a Facebook initial public offering, he harks back to the Google IPO in 2004. Many at the time said Google’s debut had reopened the IPO window that had closed with the bursting of the tech bubble, and a flood of new tech companies would come to market. It didn’t happen.

What Google showed, Mr. Thiel says, is that the “threshold” for going public had ratcheted up in a Sarbanes-Oxley world. Even for a well-established, profitable company—which Google was at the time—the “cost-benefit trade-off” was firmly on the side of staying private for as long as possible.

Mr. Thiel was early enough in the Facebook story to see himself portrayed in the fictionalized movie about its birth, “The Social Network.” (He’s the stocky venture capitalist who implicitly—very implicitly—sets the ball rolling toward cutting out Facebook’s allegedly victimized cofounder, Eduardo Saverin.)

Today, Mr. Thiel (the real one) has no remit to discuss the company’s many controversies. Suffice it to say, though, he believes the right company “won” the social media wars—the company that was “about meeting real people at Harvard.”

Its great rival, MySpace, founded in Los Angeles, “is about being someone fake on the Internet; everyone could be a movie star,” he says. He considers it “very healthy,” he adds, “that the real people have won out over the fake people.”

Only one thing troubles him: “I think it’s a problem that we don’t have more companies like Facebook. It shouldn’t be the only company that’s doing this well.” Maybe this explains why he recently launched a $2 million fund to support college kids who drop out to pursue entrepreneurial ventures.

Mr. Thiel is phlegmatic about his own hedge fund, which took a nasty hit last year after being blindsided by the market’s partial recovery from the panic of 2008. Listening between the lines, one senses he faces an uphill battle to convince others of his long-term view, which he insists is “not hopelessly pessimistic.”

“People don’t want to believe that technology is broken. . . . Pharmaceuticals, robotics, artificial intelligence, nanotechnology—all these areas where the progress has been a lot more limited than people think. And the question is why.”

In true macro sense, he sees that failure as central to our current fiscal fix. Credit is about the future, he says, and a credit crisis is when the future turns out not as expected. Our policy leaders, though, have yet to see this bigger picture. “Bernanke, Geithner, Summers—you may not agree with the them ideologically, but they’re quite good as macroeconomists go,” Mr. Thiel says. “But the big variable that they’re betting on is that there’s all this technological progress happening in the background. And if that’s wrong, it’s just not going to work. You will not get this incredible, self-sustaining recovery.

And President Obama? “I’m not sure I’d describe him as a socialist. I might even say he has a naive and touching faith in capitalism. He believes you can impose all sorts of burdens on the system and it will still work.”

The system is telling him otherwise. Mankind, says Mr. Thiel, has no inalienable right to the progress that has characterized the last 200 years. Today’s heightened political acrimony is but a foretaste of the “grim Malthusian” politics ahead, with politicians increasingly trying to redistribute the fruits of a stagnant economy, loosing even more forces of stagnation.

Question: How can anyone know science and technology are under-performing compared to potential? It’s hard, he admits. Those who know—”university professors, the entrepreneurs, the venture capitalists”—are “biased” in favor of the idea that rapid progress is happening, he says, because they’re raising money. “The other 98%”—he means you and me, who in this age of specialization treat science and technology as akin to magic—”don’t know anything.”

But look, he says, at the future we once portrayed for ourselves in “The Jetsons.” We don’t have flying cars. Space exploration is stalled. There are no undersea cities. Household robots do not cater to our needs. Nuclear power “we should be building like crazy,” he says, but we’re sitting on our hands. Or look at today’s science fiction compared to the optimistic vision of the original “Star Trek”: Contemporary science fiction has become uniformly “dystopian,” he says. “It’s about technology that doesn’t work or that is bad.”

The great exception is information technology, whose rapid advance is no fluke: “So far computers and the Internet have been the one sector immune from excessive regulation.”

Mr. Thiel delivers his views with an extraordinary, almost physical effort to put his thoughts in order and phrase them pithily. Somewhere in his 42 years, he obviously discovered the improbability of getting a bold, unusual argument translated successfully into popular journalism.

Mr. Thiel sees truth in three different analyses of our dilemma. Liberals, he says, blame our education system, but liberals are the last ones to fix it, just wanting to throw money at what he calls a “higher education bubble.”

“University administrators are the equivalent of subprime mortgage brokers,” he says, “selling you a story that you should go into debt massively, that it’s not a consumption decision, it’s an investment decision. Actually, no, it’s a bad consumption decision. Most colleges are four-year parties.”

Libertarians blame too much regulation, a view he also shares (“Get rid of the FDA,” he says), but “libertarians seem incapable of winning elections. . . . There are a lot of people you can’t sell libertarian politics to.”

A conservative diagnosis would emphasize an unwillingness to sacrifice, necessary for great progress, and once motivated by war. “Technology has made war so catastrophic,” he says, “that it has unraveled the whole desirability of it [as a spur to technology].”

Mr. Thiel has dabbled in activism to the minor extent of co-hosting in Manhattan last month a fund raiser for gay Republicans, but he has little taste for politics. Still, he considers it a duty to put on the table the idea that technological progress has stalled and why. (To this end, he’s working on a book with Russian chess champion and democracy activist Garry Kasparov.)

You don’t have to agree with every jot to recognize that his view is essentially undisputable: With faster innovation, it would be easier to dig out of our hole. With enough robots, even Social Security and Medicare become affordable.

Mr. Thiel has not found any straight line, however, between his macro insight and macro-investing success. “It’s hard to know how to play the macro trend,” he acknowledges. “I don’t think it necessarily means you should be short everything. But it does mean we’re stuck in a period of long-term stagnation.”

Some companies and countries will do better than others. “In China and India,” he says, “there’s no need for any innovation. Their business model for the next 20 years is copy the West.” The West, he says, needs to do “new things.” Innovation, he says, comes from a “frontier” culture, a culture of “exceptionalism,” where “people expect to do exceptional things”—in our world, still an almost uniquely American characteristic, and one we’re losing.

“If the universities are dominated by politicians instead of scientists, if there are ways the government is too inefficient to work, and we’re just throwing good money after bad, you end up with a nearly revolutionary situation. That’s why the idea that technology is broken is taboo. Really taboo. You probably have to get rid of the welfare state. You have to throw out Keynesian economics. All these things would not work in a world where technology is broken,” he says.

Perhaps it really does fall to some dystopian science fiction writer to tell us what such a world will be like—when nations are unraveling even as a cyber-nation called “Facebook” is becoming the most populous on the planet.

Mr. Jenkins writes the Journal’s Business World column.