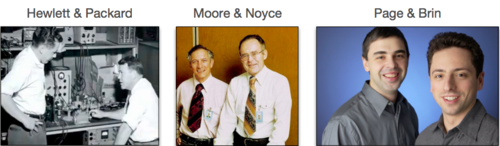

I am still not sure how Thiel’s class notes on start-ups will finish, but they are more and more fascinating, class after class. At least his vision of this world is.

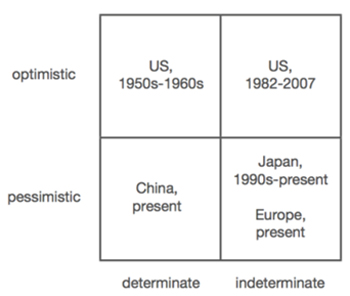

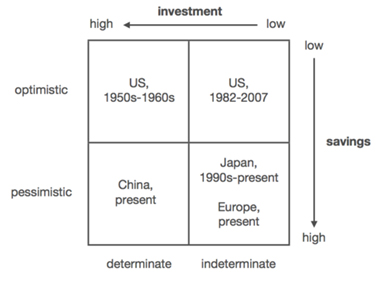

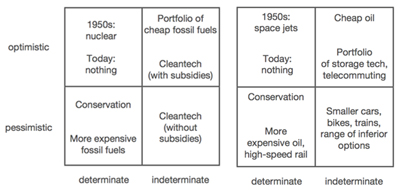

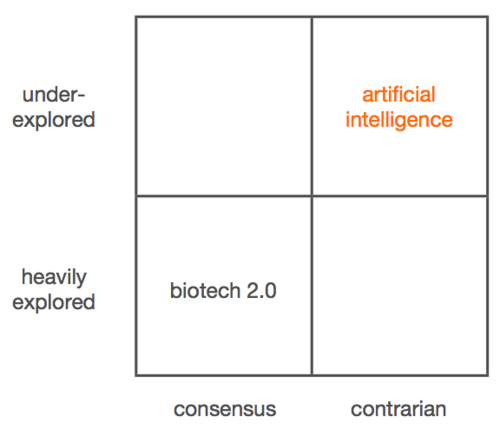

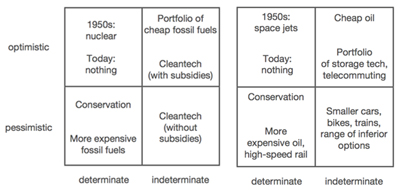

Class 14 is about cleantech and energy. “Alternative energy and cleantech have attracted an enormous amount of investment capital and attention over the last decade. Almost nothing has worked as well as people expected. The cleantech experience can thus be quite instructive. […] To think about the future of energy, we can use the [another] matrix. The quadrants shake out like this:

– Determinate, optimistic: one specific type of energy is best, and needs to be developed

– Determinate, pessimistic: no technology or energy source is considerably better. You have what you have. So ration and conserve it.

– Indeterminate, optimistic: there are better and cheaper energy sources. We just don’t know what they are. So do a whole portfolio of things.

– Indeterminate, pessimistic: we don’t know what the right energy sources are, but they’re likely going to be worse and expensive. Take a portfolio approach.”

Both for energy and transportation, Thiel’s fills his quadrants with interesting examples:

and he adds: “Petroleum has dominated transportation. Coal has dominated in power generation. […] Typically a single source dominates at any given time. There is a logical reason for this. It doesn’t make sense that the universe would be ordered such that many different kinds of energy sources are almost exactly equal. Solar is very different from wind, which is very different from nuclear. It would be extremely odd if pricing and effectiveness across all these varied sources turned out to be virtually identical. So there’s a decent ex ante reason why we should expect to see one dominant source. This can be framed as a power law function. Energy sources are probably not normally distributed in cost or effectiveness. There is probably one that is dramatically better than all others.”

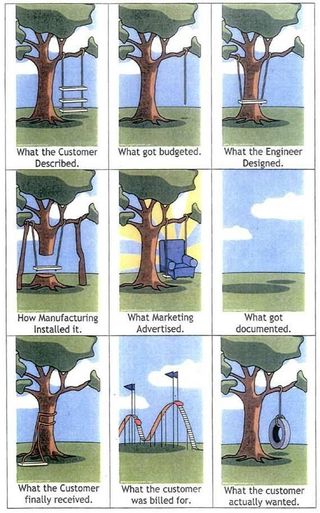

But the analysis explaining the cleantech bubble were far from clear. “One problem was that people were ambiguous on what was scarce or problematic. Was there resource scarcity? Or were the main problems environmental?” […] “To have a successful startup, you must have good answers—or at least a good plan for getting those answers.” Answers to many issues such as

– the market

– the secrets

– the team and its culture

– the funding

and unfortunately many mistakes were made.

Regarding the market, there was the issue of both explaining how to become a leader of one segment (PV, wind,…) and why a segment was better. Regarding the secret: “If you want to start a company, you should have some important secret. But in practice, most wind, solar, and cleantech ventures relied on incremental improvements.” Even worse, “most cleantech companies in the last decade have had shockingly non-technical teams and cultures. Culture defaulted toward zero-sum competition. Savvy observers would have seen the trouble coming when cleantech people started wearing suits and ties. Tech people and computer people wear t-shirts and jeans. Cleantech people, by contrast, looked like salesmen. And indeed they were. This is not a trivial point. If you’re dealing in something that’s incremental and of questionable durability, you actually have to be a really good salesman to convince people that it’s dramatically better.” Finally “a good, broad rule of thumb is to never invest in companies who are looking for less than $1 million or more than $1 billion. If companies can do everything they want for less than a million dollars, things may be a little too easy. There may be nothing that is very hard to build, and it’s just a timing game. On the other extreme, if a company needs more than a billion dollars to be successful, it has to become so big that the story starts to become implausible.”

If Thiel were to bet on soemthing, it would apparently be Thorium as a nuclear fuel.

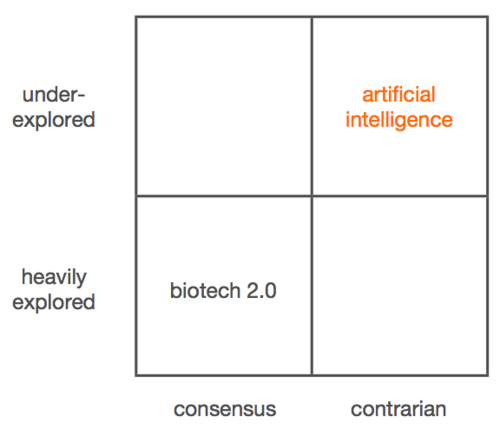

Class 15 is about other future bets.

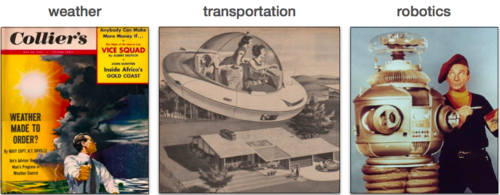

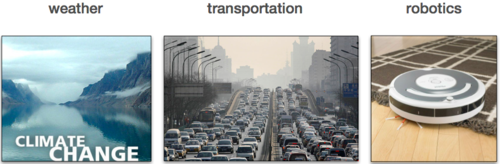

Thiel is a strong believer in contrarian (and sometimes huge) bets. He is interested in or at least puzzled by transportation, robotics, weather and energy storage. And his way of choosing is to look at what did not work (yet) in the past: “Various VC firms in Silicon Valley warned expressed concern about [investing in unique technologies]. They warned us that investing in SpaceX was risky and maybe even crazy. And this wasn’t even at the very early stage. […] (Danielle Fong:) People like to act like they like being disruptive and taking risks. But usually it’s just an act. They don’t mean it. Or if they do, they don’t necessarily have the clout within the partnership to make it happen. (Peter Thiel:) It is very hard hard for investors to invest in things that are unique. The psychological struggle is hard to overstate. People gravitate to the modern portfolio approach. The narrative that people tell is that their portfolio will be a portfolio of different things. But that seems odd. Things that are truly different are hard to evaluate. […] The upside to doing something that you’re unfamiliar with, like rockets, is that it’s likely that no one else is familiar with it, either. The competitive bar is lowered. You can focus on learning and substantive things over process, which is perhaps better than competing against experts.”

Class 16 is about maybe the highest of all bets: life and death.

I have not so far mentioned the sentence which comes at the top of each series of class notes: “Your mind is software. Program it. Your body is a shell. Change it. Death is a disease. Cure it. Extinction is approaching. Fight it.”

The problem.

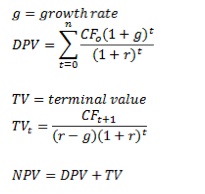

“Like death itself, modern drug discovery is probably too much a matter of luck. Scientists start with something like 10,000 different compounds. After an extensive screening process, those 10,000 are reduced to maybe 5 that might make it to Phase 3 testing. Maybe 1 makes it through testing and is approved by the FDA. It is an extremely long and fairly random process. This is why starting a biotech company is usually a brutal undertaking. Most last 10 to 15 years. There’s little to no control along the way. What looks promising may not work. There’s no iteration or sense of progress. There is just a binary outcome at end of a largely stochastic process. You can work hard for 10 years and still not know if you’ve just wasted your time.

To be fair, we must acknowledge that all the luck-driven, stats-driven processes that have dominated people’s thinking have worked pretty well over the last few decades. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that indeterminacy is sound practice. Its costs may be rising quickly. Perhaps we’ve found everything that is easy to find. If so, it will be hard to improve armed with nothing but further random processes. This is reflected in escalating development costs. It cost $100 million to develop a new drug in 1975. Today it costs $1.3 billion. Probably all life sciences investment funds have lost money. Biotech investment has been roughly as bad a cleantech.”

The perspectives.

“Drug discovery is fundamentally a search problem. The search space is extremely big. There are lots of possible compounds. An important question is thus whether we can use computer technology to reduce scope of luck. Can Computer Science make biotech more determinative?”

“These are big secrets that play out over long time horizons, not web apps that have a 6-week window to take over the world.”

“The sequencing of the genome is like the first packets being sent over ARPANET. It’s a proof of concept. This technology is happening, but it isn’t yet compelling. So there is a huge market if one can make something compelling enough for people to actually go and get a genome sequenced. It’s like e-mail or word processing. Initially these things were uncomfortable. But when they become demonstrably useful, people leave their comfort zones and adopt them.”

“Biotech got quite a burst in late 70s early 80s, with new recombinant DNA and molecular biology techniques. Genentech led the way from the late 70s to the early 80s. Nine of the 10 biggest American biotech companies were founded during this really short time. Their technology came out some 7-8 years later. And that was the window; not very many integrated biotech companies have emerged since then. There was a certain amount of stuff to find. People found it. And before Genentech, the paradigm was pharma, not biotech. That window (becoming an integrated pharmaceutical company) had been closed for about 30 years before Genentech. So the bet is that while the traditional biotech window may be closed, the comp bio window is just opening.”

“There’s really no rush to spill the secret plans. This space is very much unlike fast-moving consumer Internet startups. Here, if you have something unique, you should nurse it.”

“Slow iteration is not law of nature. Pharma and biotech usually move very slowly, but both have moved pretty fast at times. From 1920-1923 Insulin moved at the speed of software. Today, platforms like Heroku have greatly reduced iteration times. The question is whether we can do that for biotech. Nowhere is it written in stone that you can’t go from conception to market in 18 months. That depends very much on what you’re doing. Genentech was founded the same year as Apple was, in 1976. Building a platform and building infrastructure take time. There can be lots of overhead. Ancillary things can take longer than a single product lifecycle to accumulate. [… the] VC is broken with respect biotech. Biotech VCs have all lost money. They usually have time horizons that are far too short. VCs that say they want biotech tend to really want products brought to market extremely quickly. “Integrated drug platform” is an ominous phrase for VCs. More biotech VCs are focused on globalization than on real technical innovation. VCs typically found a company around a single compound and then pour a bunch of money into it to push it through the capital-intensive trial process. Most VCs not interested in multi-compound companies doing serious pre-clinical research.”

And as a conclusion of class 16, “Startups are always hard at the start. There are futons and ironing boards in the office. You have to rush to clean up for meetings. But maybe the hardest thing is just to get your foundation right and make sure you plan to build something valuable. You don’t have to do a science fair project at the start. You just have to do your analytical homework and make sure what you’re doing is valid. You have to give yourself the best chance of success as things unfold in the future.”

Class 17 is about the brain, artificial intelligence, maybe the last frontier in technology, certainly going further than the previous topics addressed here.

Not much more to add except maybe the short description of the approach by 3 start-ups:

– Vicarious is trying to build AI by develop algorithms that use the underlying principles of the human brain. They believe that higher-level concepts are derived from grounded experiences in the world, and thus creating AI requires first solving a human sensory modality.

– Prior Knowledge (acquired by Salesforce since Thiel’s class) is taking a different approach to building AI. Their goal is less to emulate brain function and more to try to come up with different ways to process large amounts of data. They apply a variety of Bayesian probabilistic techniques to identifying patterns and ascertaining causation in large data sets. In a sense, it’s the opposite of simulating human brains.

– The big insight at Palantir (…) isn’t regression analysis, where you look at what was done in the past to try to predict what’s going to be next. A better approach is more game theoretic. Palantir’s framework is not fundamentally about AI, but rather about intelligence augmentation.

And one more comment: “For the most part, academics aren’t (working on strong AI or crazy things) because their incentive structure is so weird. They have perverse incentive to make only marginally better things. And most private companies aren’t working on it because they’re trying to make money now.(…) Bold claims also require extraordinary proof. If you’re pitching a time machine, you’d need to be able to show incremental progress before anyone would believe you. Maybe your investor demo is sending a shoe back in time. That’d be great. You can show that prototype, and explain to investors what will be required to make the machine work on more valuable problems. It’s worth noting that, if you’re pitching a revolutionary technology as opposed to an incremental one, it is much better to find VCs who can think through the tech themselves. When Trilogy was trying to raise their first round, the VCs had professors evaluate their approach to the configurator problem. Trilogy’s strategy was too different from the status quo, and the professors told the VCs that it would never work. That was an expensive mistake for those VCs. When there’s contrarian knowledge involved, you want investors who have the ability to think through these things on their own.”

End of part 5!