Following my recent post about Wasserman’s book, The Founder’s Dilemmas, let me react about recent (and less recent) events related to Swiss start-ups and founders. Do we have here the same dilemmas Americans face, that is building a company which is either control-oriented or wealth-oriented? If you do not know what I mean, read the blog or let me just add that there is this binary model of either slowly creating value with your customers and partners with not much investor money or taking the risk of fast growth with investors, in anticipation of customer demand.

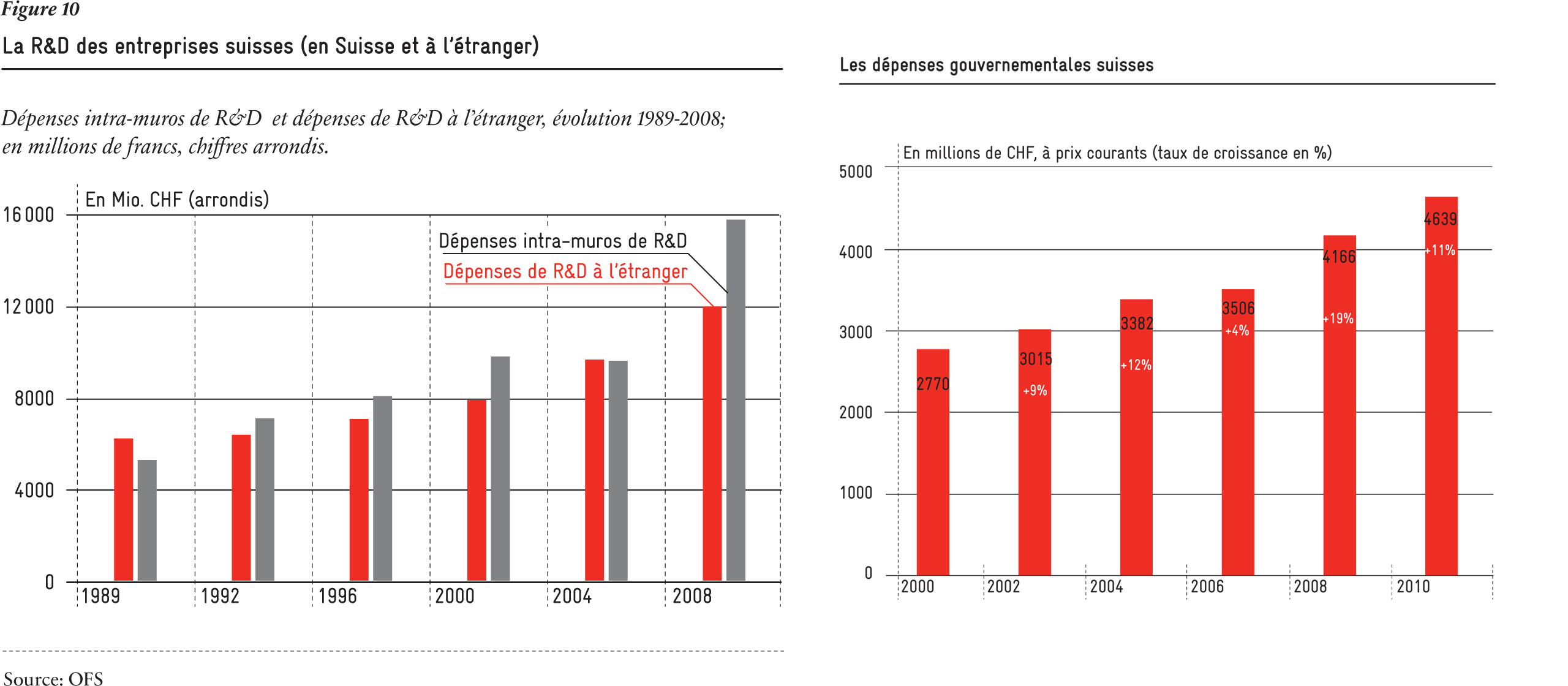

The ultimate example of this in Wasserman’s book is Evan Williams who founded Blogger, Oddeo and then Twitter, with diverse strategies. Paul Graham addresses the issue often (for example in Startup = Growth or in How to Make Wealth) and for a young entrepreneur, getting a million can be very important. At the macro-economic level, there is also a debate which I honestly never really understood. I think an ecosystem is (or should be) interested in fast growing companies, and slow growth should be less of a focus, not because it would not be important, but because it has always existed and will continue to exist with or without public support… However, because there are many SMEs in Switzerland, the support to small firms seems to be important. So is the situation very different from what I know in the USA? Let me try a simple description.

Sensirion is a very succesful Swiss start-up which is a good illustration of the debate. In an article written in 2008, its co-founder, Felix Mayer wrote about “How to finance the Growth? Being somewhere in the middle between the “US American” who is shooting for the moon and the Swiss who develops his technology on the cash flow of a one man company we did not choose the classical venture capital path to finance the first growth phase of the company but were able to find a private investor. In Switzerland, if you look for private investors, you may find experienced entrepreneurs who are willing to invest into a promising business. They are also known as “business angels”. It took quite a while to get from a prototype to a product family or from 1 to 10 to 100 as described before. You need knowledgeable and patient partners to survive this phase with many ups and downs. Usually, it takes longer than you expect. Nevertheless, at the end of the day, you have to get to the point where you generate growth by your own cash flow, which Sensirion reached 6 years after its incorporation. Since then, we generate enough cash flow to finance our yearly growth of around 30%-40%. In order to manage this growth we are of course continuously looking for excellent people!”

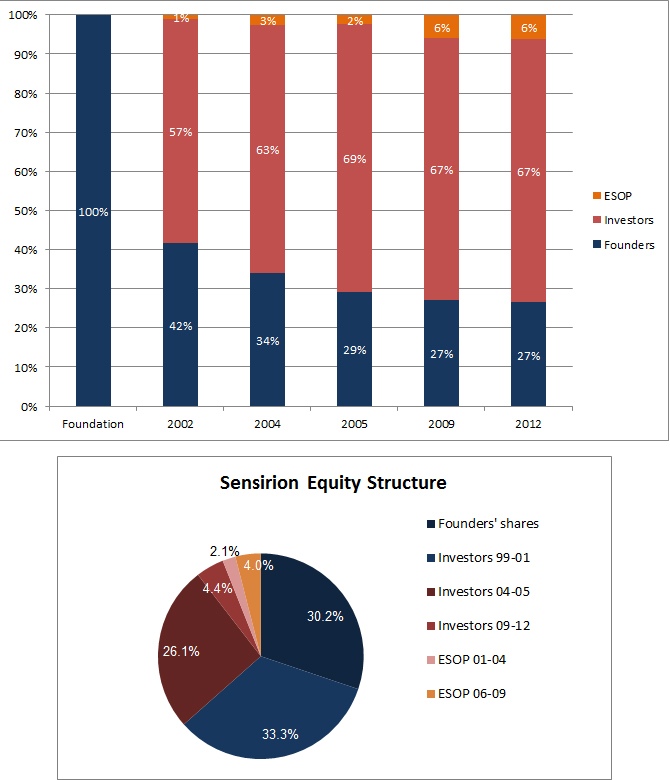

Is Sensirion a different model? I went to the Swiss register of commerce and looked at Sensirion financing (the Canton of Zurich is offering very detailed information). It was not an easy exercice and I am not sure about the accuracy (You will see the figures differ slightly!). I tried also to show the dilution of founders over time:

and here is Sensirion employee growth since its inception

Sensirion is clearly a success story, but is it that different from the US model? There might be no VC, but the private investor(s) have put a total of CHF13M with a valuation of CHF190M at the last round. The growth was as fast as many VC-backed start-ups, so I am not sure the investors were more patient and the exit might be less of a priority. This is very similar to many US start-ups… But Sensirion is often mentioned as an example that start-ups would not need venture capital (hence investors). There is not that much difference between a private investor and a VC (or is there?)

Now it is true that many of the Top 100 Swiss Start-ups raise very little money with business angels In the order of CHF1-2M. Recently EPFL’s Jilion has been acquired by Dailymotion for an undisclosed amount and the local press mentions Jilion had raised about one million. Optotune in Zurich is a similar model with 200’000 raised according to the register of commerce. Techcrunch was concerned recently about BugBuster (small) CHF1M A round. Dacuda raised about one million too at a CHF7M valuation. LiberoVision raised CHF200k with Swisscom at a CHF2.5M value before being bought for about CHF8M (it might have been more with upsides). Netbreeze was acquired by Microsoft after raising about CHF5M from one group of investors which owned 80% of the company. Wuala was acquired by LaCie 2 years after its creation and it was totally self-funded. And the list is nearly endless.

But there are also fast growing companies. Covagen, GlyxoVaxyn, GetYourGuide, InSphero, Molecular Partners, Nexthink, TypeSafe, UrTurn have raised a lot of money with VCs. And people who would say Switerland is about health related firms will see it is more diverse…

| Company | Field | Money raised | Latest valuation | Investors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covagen | Biotech | 56M | NA | Gimv, Ventech, Rotschild |

| GetYourGuide | Internet | 16M | 50M | Highland |

| GlycoVaxyn | Biotech | 50M | 37M | Sofinnova, Index, Rotschild |

| InSphero | Biotech | 4M | 16M | Redalpine, ZKB |

| Molecular Partners | Biotech | 56M | 115M | Index, BB Biotech |

| Nexthink | Software | 15M | NA | VI, Auriga |

| Sensirion | Electronics | 13M | 190M | Undisclosed |

| TypeSafe | Software | 16M | NA | Greylock |

| UrTurn | Internet | 12M | 36M | Balderton |

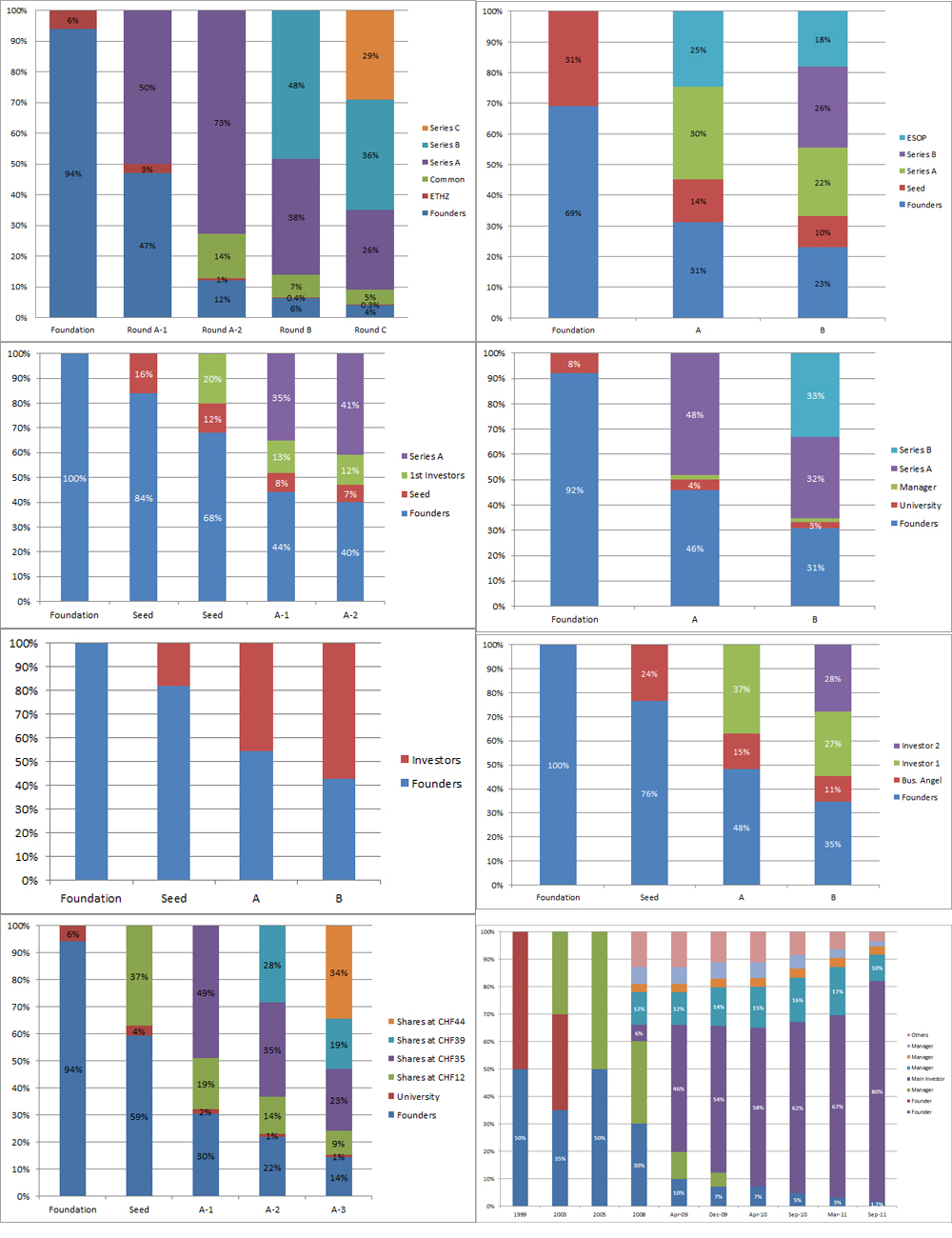

And of course, the founders have been diluted. I will not specifically show the dilution in each company but anonymously illustrate this with the data I could found online (non confidential data).

| Company | Founders | Seed | A | B & Later | ESOP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9% | 26% | 65% | ||

| 2 | 30% | 33% | 31% | 6% | |

| 3 | 34% | 32% | 33% | ||

| 4 | 40% | 7% | 12% | 41% | |

| 5 | 43% | 47% | 10% | ||

| 6 | 35% | 11% | 27% | 28% |

I am not sure, with all this data, that Switzerland is qualitatively that different… I will finish with an interview of Daniel Borel, the co-founder of Logitech: “The only answer that I may provide is the cultural difference between the USA and Switzerland. When we founded Logitech, as Swiss entrepreneurs, we had to enter very soon the international scene. The technology was Swiss but the USA, and later the world, defined our market, whereas production quickly moved to Asia. I would not like to look too affirmative because many things change and many good things are done in Switzerland. But I feel that in the USA, people are more opened. When you receive funds from venture capitalists, you automatically accept an external shareholder who will help you in managing your company and who may even fire you. In Switzerland is not very well accepted. One prefers a small pie that is fully controled to a big pie that one only controls at 10%, and this may be a limiting factor”