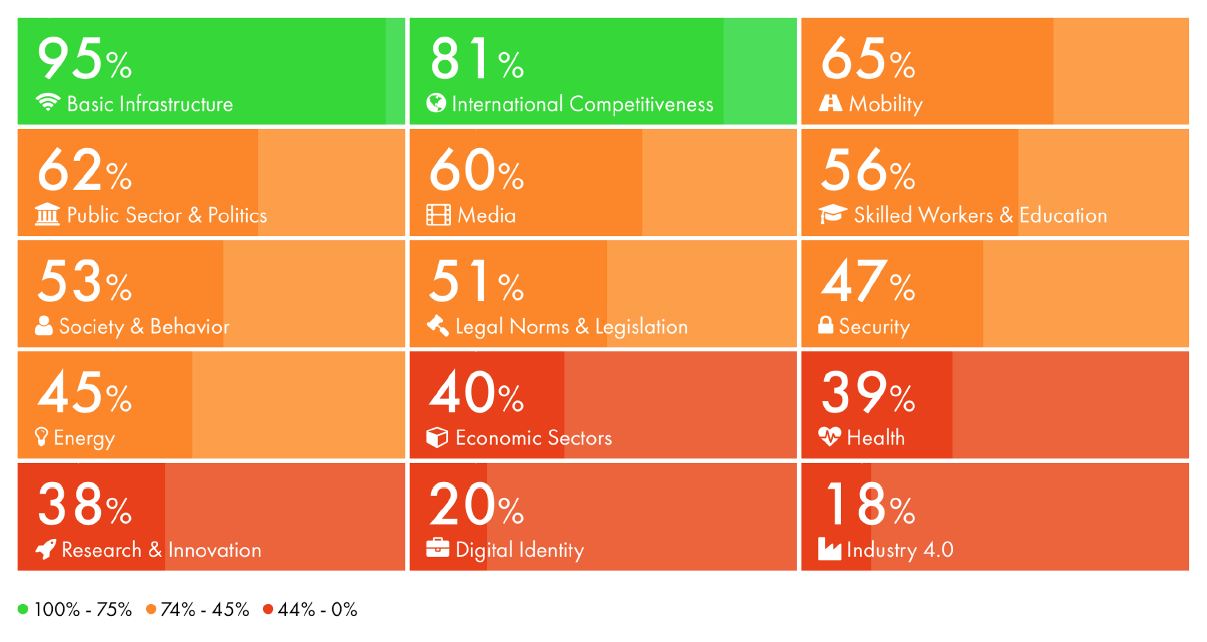

I just read two great reports about entrepreneurship. The first one is the Global Entrepreneurship Index 2016 (GEI). The second one is the Startup Playbook by Sam Altman (Ycombinator). Whereas the second one is about the micro features of entrepreneurship, the GEI is a worldwide macro-economic analysis. I will cover the Startup Playbook in the part 2 of these series of posts, so let me focus here in the GEI.

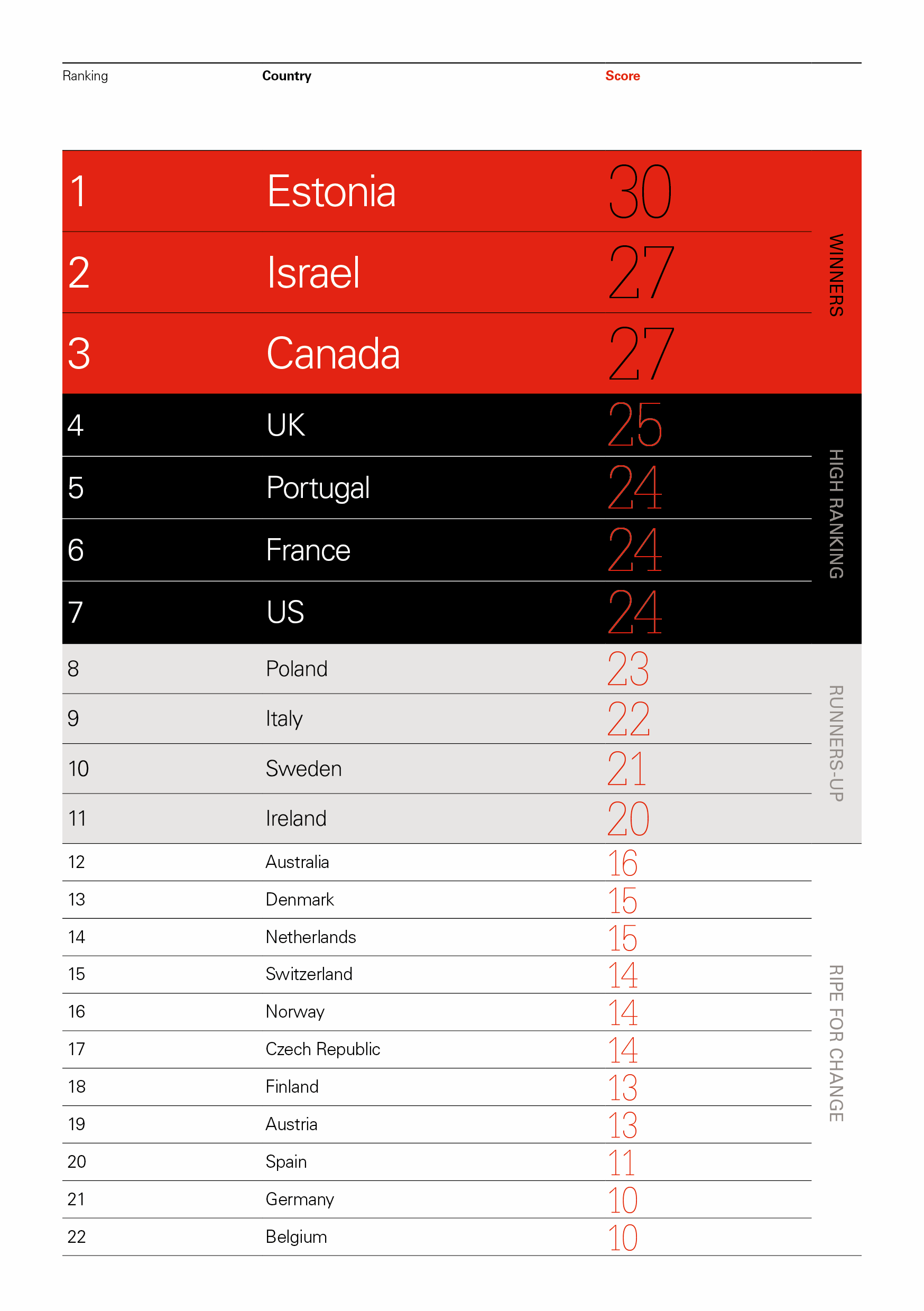

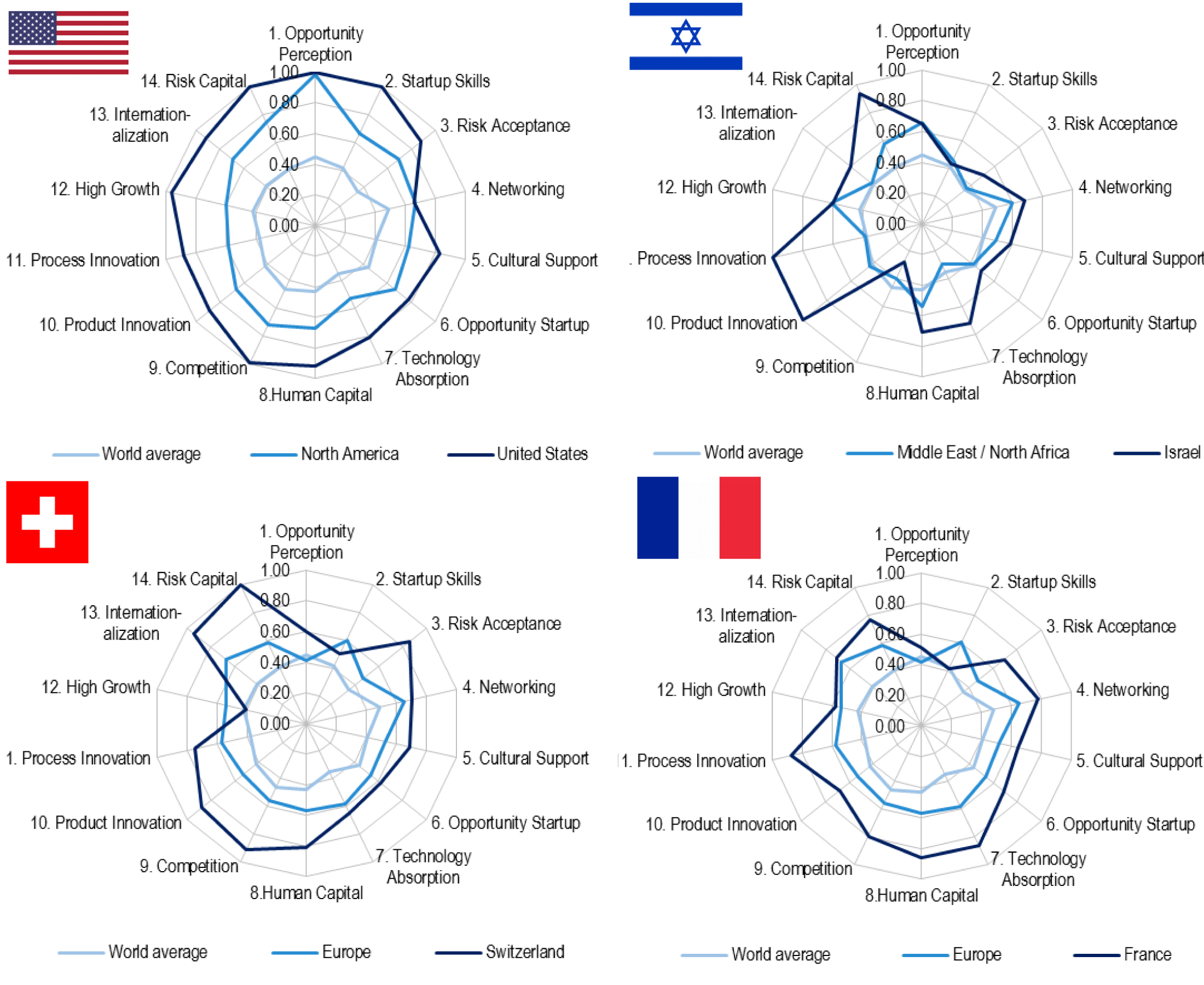

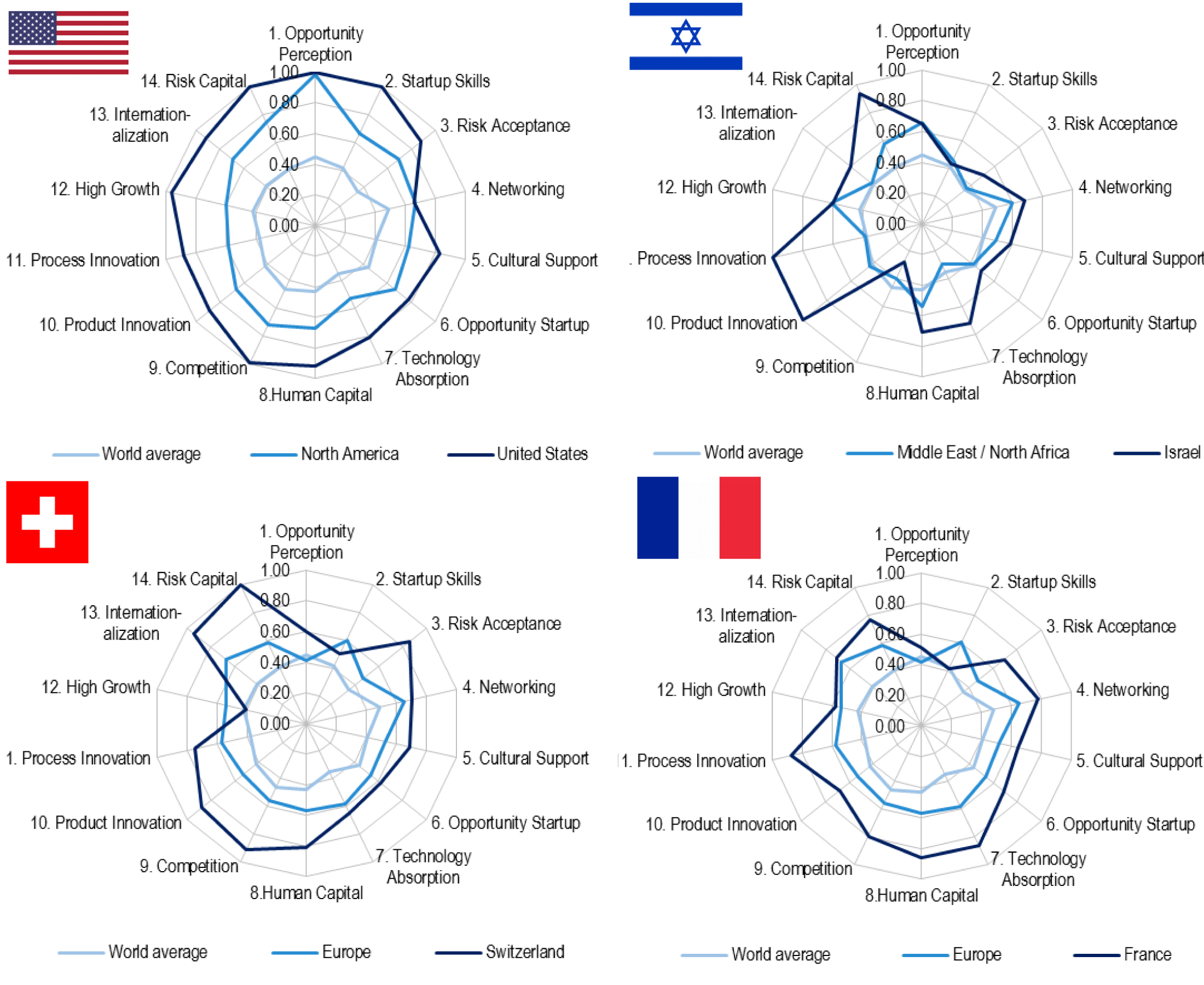

What I found really interesting is that compared to the Global Innovation Index (GII) about which I always have doubts – I think it measures more the inputs necessary for innovation than the outputs – I feel much more comfortable with the criteria and results of the GEI. For example, the USA is number one which makes a lot of sense and Switzerland is #8. Switzerland is #1 in the GII which is some kind of a mystery to me. France and Israel are #10 and #21 in the GEI but #20 and #21 in the GII.

The 3 As of Entrepreneurship

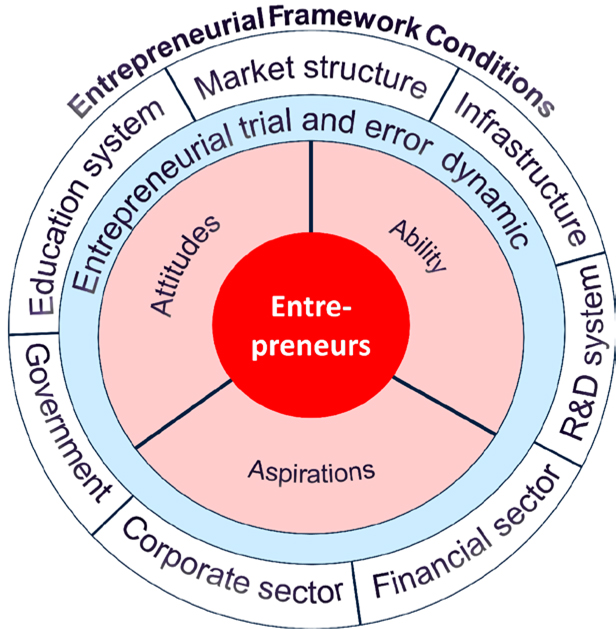

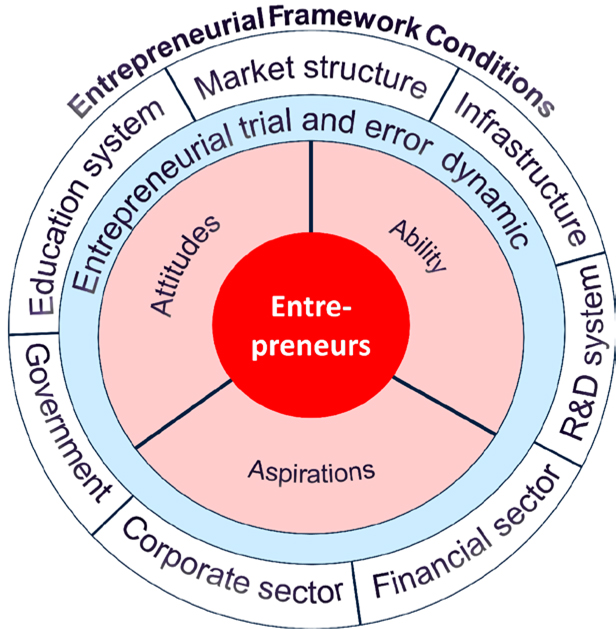

So how is this measured? The authors define 3 framework conditions entrepreneurship: attitudes, abilities and aspirations.[Pages 26-27 of the document or 49-50 of the pdf]. They also define 14 related pillars [Pages 19-22 of the document or 42-45 of the pdf]

Entrepreneurial attitudes are societies’ attitudes toward entrepreneurship, which we define as a population’s general feelings about recognizing opportunities, knowing entrepreneurs personally, endowing entrepreneurs with high status, accepting the risks associated with business startups, and having the skills to launch a business successfully. The benchmark individuals are those who can recognize valuable business opportunities and have the skills to exploit them; who attach high status to entrepreneurs; who can bear and handle startup risks; who know other entrepreneurs personally (i.e., have a network or role models); and who can generate future entrepreneurial activities.

Moreover, these people can provide the cultural support, financial resources, and networking potential to those who are already entrepreneurs or want to start a business. Entrepreneurial attitudes are important because they express the general feeling of the population toward entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship. Countries need people who can recognize valuable business opportunities, and who perceive that they have the required skills to exploit these opportunities. Moreover, if national attitudes toward entrepreneurship are positive, it will generate cultural support, financial support, and networking benefits for those who want to start businesses.

Entrepreneurial abilities refer to the entrepreneurs’ characteristics and those of their businesses. Different types of entrepreneurial abilities can be distinguished within the realm of new business efforts. Creating businesses may vary by industry sector, the legal form of organization, and demographics—age, education, etc. We define entrepreneurial abilities as startups in the medium- or high-technology sectors that are initiated by educated entrepreneurs, and launched because of someone being motivated by an opportunity in an environment that is not overly competitive. In order to calculate the opportunity startup rate, we use the GEM TEA Opportunity Index. TEA captures new startups not only as the creation of new ventures but also as startups within existing businesses, such as a spinoff or other entrepreneurial effort. Differences in the quality of startups are quantified by the entrepreneur’s education level—that is, if they have a postsecondary education—and the uniqueness of the product or service as measured by the level of competition. Moreover, it is generally maintained that opportunity motivation is a sign of better planning, a more sophisticated strategy, and higher growth expectations than “necessity” motivation in startups.

Entrepreneurial aspiration reflects the quality aspects of startups and new businesses. Some people just hate their employer and want to be their own boss, while others want to create the next Microsoft. Entrepreneurial aspiration is defined as the early-stage entrepreneur’s effort to introduce new products and/or services, develop new production processes, penetrate foreign markets, substantially increase their company’s staff, and finance their business with formal and/or informal venture capital. Product and process innovation, internationalization, and high growth are considered the key characteristics of entrepreneurship. Here we added a finance variable to capture the informal and formal venture capital potential that is vital for innovative startups and high-growth firms.

Each of these three building blocks of entrepreneurship influences the other two. For example, entrepreneurial attitudes influence entrepreneurial abilities and entrepreneurial aspirations, while entrepreneurial aspirations and abilities also influence entrepreneurial attitudes.

The 14 Pillars of Entrepreneurship

The pillars of entrepreneurship are many and complex. While a widely accepted definition of

entrepreneurship is lacking, there is general agreement that the concept has numerous dimensions. […] Considering all of these possibilities and limitations, we define entrepreneurship as “the dynamic, institutionally embedded interaction between entrepreneurial attitudes, entrepreneurial abilities, and entrepreneurial aspirations by individuals, which drives the allocation of resources through the creation and operation of new ventures.”

Entrepreneurial Attitudes Pillars

Pillar 1: Opportunity Perception. This pillar captures the potential “opportunity perception” of a population by considering the size of its country’s domestic market and level of urbanization. Within this pillar is the individual variable, Opportunity Recognition, which measures the percentage of the population that can identify good opportunities to start a business in the area where they live. However, the value of these opportunities also depends on the size of the market. The institutional variable Market Agglomeration consists of two smaller variables: the size of the domestic market (Domestic Market) and urbanization (Urbanization). The Urbanization variable is intended to capture which opportunities have better prospects in developed urban areas than they do in poorer rural areas.

Pillar 2: Startup Skills. Launching a successful venture requires the potential entrepreneur to have the necessary startup skills. Skill Perception measures the percentage of the population who believe they have adequate startup skills. Most people in developing countries think they have the skills needed to start a business, but their skills usually were acquired through workplace trial and error in relatively simple business activities. In developed countries, business formation, operation, management, etc., requires skills that are acquired through formal education and training. Hence education, especially postsecondary education, plays a vital role in teaching and developing entrepreneurial skills.

Pillar 3: Risk Acceptance. Of the personal entrepreneurial traits, fear of failure is one of the most important obstacles to a startup.

Pillar 4: Networking. Networking combines an entrepreneur’s personal knowledge with their ability to use the Internet for business purposes. This combination serves as a proxy for networking, which is also an important ingredient of successful venture creation and entrepreneurship.

Pillar 5: Cultural Support. This pillar is a combined measure of how a country’s inhabitants view entrepreneurs in terms of status and career choice, and how the level of corruption in that country affects this view.

Entrepreneurial Abilities Pillars

Pillar 6: Opportunity Startup. This is a measure of startups by people who are motivated by opportunity but face regulatory constraints. An entrepreneur’s motivation for starting a business is an important signal of quality. Opportunity entrepreneurs are believed to be better prepared, to have superior skills, and to earn more than what we call necessity entrepreneurs.

Pillar 7: Technology Absorption. In the modern knowledge economy, information and communication technologies (ICT) play a crucial role in economic development. Not all sectors provide the same chances for businesses to survive and or their potential for growth. The Technology Level variable is a measure of the businesses that are in technology sectors.

Pillar 8: Human Capital. The prevalence of high-quality human capital is vitally important for ventures that are highly innovative and require an educated, experienced, and healthy workforce to continue to grow.

Pillar 9: Competition. Competition is a measure of a business’s product or market uniqueness, combined with the market power of existing businesses and business groups.

Entrepreneurial Aspirations Pillars

Pillar 10: Product Innovation. New products play a crucial role in the economy of all countries. New Product is a measure of a country’s potential to generate new products and to adopt or imitate existing products.

Pillar 11: Process Innovation. Applying and/or creating new technology is another important feature of businesses with high growth potential. New Tech is defined as the percentage of businesses whose principal underlying technology is less than five years old.

Pillar 12: High Growth. This is a combined measure of the percentage of high-growth businesses that intend to employ at least ten people and plan to grow more than 50 percent in five years (Gazelle variable) with business strategy sophistication (Business Strategy variable).

Pillar 13: Internationalization. Internationalization is believed to be a major determinant of growth. A widely applied proxy for internationalization is exporting.

Pillar 14: Risk Capital. The availability of risk finance, particularly equity rather than debt, is an essential precondition for fulfilling entrepreneurial aspirations that are beyond an individual entrepreneur’s personal financial resources.

The reason I really felt synchronized with the authors (congrats to Zoltán J. Ács, László Szerb, Erkko Autio for the great work!) is a final extract from pages 63-64 (86-87 of the pdf): they explain the challenges and related mistakes and describe better approaches.

Unfortunately, although high-growth entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial ecosystems are high on many policy agendas, there is fairly little understanding of how policy can foster them most effectively. Most entrepreneurship policy playbooks remain stuck with old world policy approaches, which focus on identifying and fixing “market failures” and “structural failures.” Such approaches, while effective in addressing well-specified market and structural failures, are hopelessly inadequate to deal with the complexities of entrepreneurial ecosystems.

A classic example of a market failure is the failure of businesses to invest in R&D. Because R&D is a risky and uncertain activity, many firms are tempted to wait, to let others to take the risk, and then quickly copy successful projects. But if everyone thought this way, no one would invest in R&D, and innovative activities would stagnate. Therefore, governments address this market failure by providing subsidies for R&D—in effect, participating in the downside risk while allowing firms to keep the upside returns.

In contrast to subsidizing specific activities, a structural failure policy would seek to build support services and structures that support new firm creation and growth. Examples of structural failure policies include, for example, the creation of science parks and business incubators to shelter and support startup ventures.

Both of these approaches fail to address the complexities of entrepreneurial ecosystems, which are too complex to allow easy identification of specific clean-cut market failures, such as insufficient investment in R&D. The “product” entrepreneurial ecosystems produce is innovative and high-growth new ventures. Creating high-growth new ventures is a far more complex undertaking than starting an R&D project. If we do not see a sufficient number of high-growth new ventures, where exactly is the market failure supposed to reside? The standard approach by governments, which is consistent with market failure thinking, is that there perhaps is not sufficient support funding available to start new, high-growth firms. However, as much as governments have provided subsidies to support new firm creation, the results have not been very encouraging.

Another major problem with both market failure and structural failure approaches is that they are top-down, where the policy maker analyzes, designs, and implements entrepreneurship policy. Top-down, however, is not a feasible approach in entrepreneurial ecosystems that consist of multiple independent stakeholders. In such situations, a policymaker cannot simply command and control, as you have no formal authority over ecosystem stakeholders. Instead, policymakers need to engage the various stakeholders and co-opt them as active participants and contributors to the policy intervention.

[…]

Entrepreneurial ecosystems are fundamentally interaction systems consisting of multiple, co-specialized, yet hierarchically independent stakeholders, many of which may not even know one another. Here, co-specialization means that different stakeholders play different roles—venture capitalists, research institutions, different supporting institutions, new ventures, established businesses, and so on. They offer complementary skills and services, and normally depend on others to accomplish their goals, which implies that team play is needed.

In the above, hierarchical independence means that there are no formal lines of command, unlike, say, within government agencies or industrial corporations. Everyone makes their own independent decisions and optimizes their own performance. Combined with co-specialization, this creates a mutual dependency dilemma: to accomplish your goals you must depend on others, yet you cannot tell others what to do. Cooperation is therefore required. This limits the usability of traditional top-down policies, which are usually implemented through formal chains of command (e.g., a government department designing a policy, which is then implemented by a government agency overseen by the department).

Also of relevance is the notion of interaction systems, which means that the stakeholders of entrepreneurial ecosystems “co-produce” their outputs, such as innovative high-growth new ventures. These outputs are coproduced through a myriad of usually uncoordinated interactions between hierarchically independent yet interdependent stakeholders. This combination of independence and interdependence makes coordination challenging.

In the GEI model, it is the entrepreneurs who drive the entrepreneurial trial-and-error dynamic. This means that entrepreneurs start new businesses to pursue opportunities that they themselves perceive. An entrepreneurial opportunity is simply a chance to make money through a new venture, such as producing and selling goods and services for profit. However, entrepreneurs can never tell in advance whether a given opportunity is real or not: the only way to validate an opportunity is to pursue it. In other words, entrepreneurs need to take risks: they need to access and mobilize resources (human, financial, physical, technological) before they can verify whether or not a profit can be made. This means, then, that not all entrepreneurial efforts will be successful, as some opportunities turn out to be mere mirages. In such cases, the budding entrepreneur will realize sooner or later that they are never going to make a profit, or that they could make more money doing something else. In such cases, the entrepreneur will abandon the current pursuit and do something else instead.

If, however, an entrepreneurial opportunity turns out to be real, the entrepreneurs will make more money pursuing that opportunity than doing something else, and they will continue to exploit it. The net outcome of this entrepreneurial trial-and-error dynamic, therefore, is the allocation of resources to productive uses. In other words, a healthy entrepreneurial dynamic within a given economy will drive total factor productivity, or the difference between inputs and outputs. The greater the total factor productivity, the greater the economy’s capacity to create new wealth.