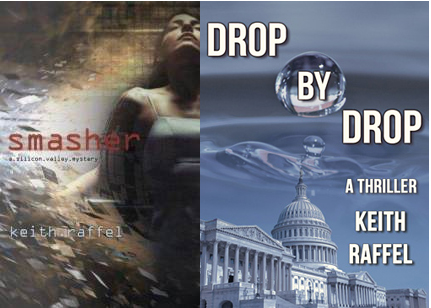

Smasher is the second Silicon Valley thriller from Keith Raffel that I read. After reading dot.dead, I found this one more complex, and certainly as interesting. A mixture of a traditional thriller where the hero’s wife is smashed by a car, together with a good start-up story where the leader in the field is trying to smash the hero’s company and an academic story of intense competition between researchers in the physics field of [smashed] particles. Hence the title Smasher.

I already mentioned novels about start-ups or Silicon Valley (dot.dead, but also The Ultimate Cure). I have never mentioned though Po Bronson (I loved The First 20 Million Is Always the Hardest) or Michael Wolff (Burn Rate). I have not read (yet) Kaplan’s Start-up. On the academic side, there is Small World by the great David Lodge which I have not read (either…) There are of course many essays on the start-up or academic worlds (I mentioned many in my past posts in the must read category) but there are clearly not so many novels based on these worlds,

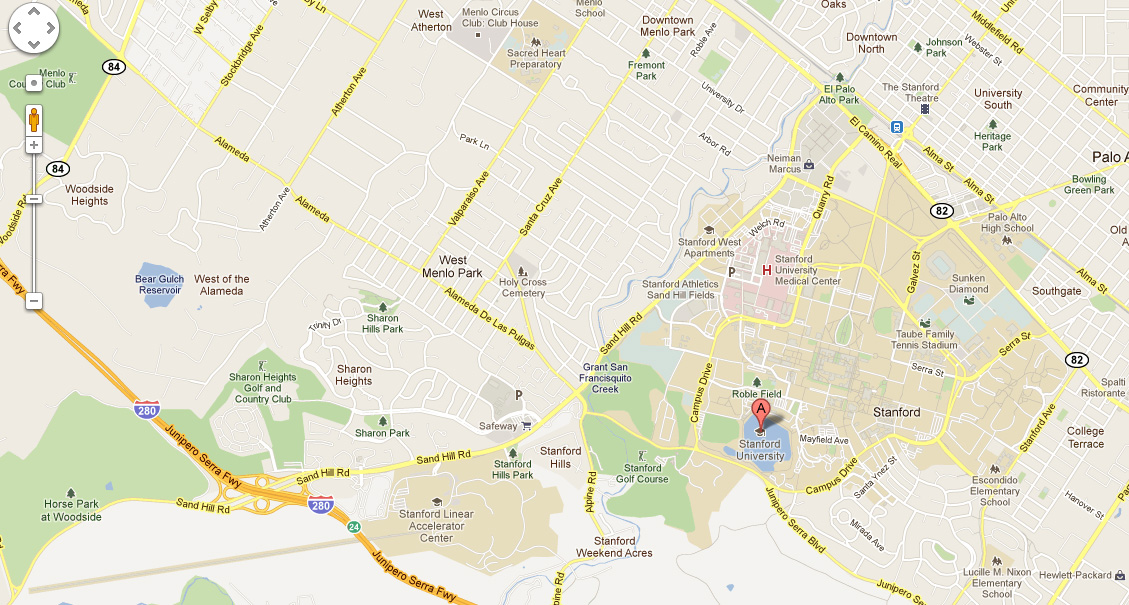

Raffel loves to take inspiration from real individuals in Silicon Valley. I had played at recognizing a few in dot.dead. Here it is less obvious; the academic smasher is a mixture of Feynman and Gell-Man. The start-up smasher looks more like Larry Ellison with his dark suits and love for Japanese architecture. But there is a little from Steve Jobs as well. The other characters existed in the first novel. I will not talk about the story and only shortly about the particle physics. I will say more about the start-up and broader Silicon Valley context. Smasher talks of Quarks and quirks, of Murray Gell-Man who got the Nobel prize for their discovery and of SLAC, the Stanford Linear Accelerator (a small CERN). You may identify SLAC both on the map and picture below.

There is indeed a link between particle physics and the start-up world. Raffel reminds us that the World Wide Web was invented at Cern thanks to Tim Berners-Lee. Slac had other spin-offs, but this is another story. Slac was also a home for the Homebrew Computer Club (see [1] and extract from page 214 below)

Smasher is also about women and science. “Stanford was on a campaign to recruit female undergraduates, Ph.D. candidates, and faculty to the natural sciences. My mother’s late aunt had been the first woman in the physics department back in the 1960s. In an effort to honor her and to appeal to what was still the second sex in the realm of natural sciences, the university was naming its particle physics lab after her. I’d lived in Palo Alto all my life and couldn’t recall a building, library, school or academic chair at Stanford labeled with a name except in return for a donation of dollars, euros, yens, dinars, or other convertible currency. So maybe Stanford was really serious about recruiting women.” And the invited professor for the ceremony adds: “We all follow in the footsteps of our predecessors. When I was a girl in France, I wanted to be Marie Curie. After two years as a graduate student at Stanford, after two years of hearing about her legacy, I wanted to be your great aunt.” (Page 12)

What may not be realistic is that this French professor smokes Gauloises (page 213). I know I left France a long time ago but I doubt professors still smoke them! It is pure work of fiction of course but Raffel adds in his acknowledgments that he found inspiration in Rosalind Franklin‘s life. A sad story which shows the complexity of being a woman in science or high-tech…

A funny (sorry for the jump for sadness to humor) quote and apparently true [2] on the academic world is “Clark Kerr once said his job as president of the University of California was to provide football for the alumni, sex for the students, and offices for the faculty. [The physics and Nobel prize professor] sanctum was twice the size of the [professor of English literature]’s but only a third the size of the business school professor [who is on the board of the hero’s start-up].” (Page 34)

It is also about VCs and term sheets. “VCs, bah. When you had no need for their money, investment offers would cascade over you like a tropical waterfall. When you could use a capital infusion – like now – the money flowed like water in a wadi, a riverbed in Sahara. In other words, it did not.” (Page 20)

“I drove west of Sand Hill Road. This was familiar territory, the Vatican of venture capitalism. In the bubble days of the late 1990s, office space on Sand Hill was the most expensive in the world. Here’s where the founders of Google, eBay, Amazon and Cisco had come, hat in hand, seeking the dollars required to turn the base metal of their dreams into stock market gold.” (Page 41)

Raffel has a few notes on Silicon Valley culture:

– “The value of Silicon Valley company wasn’t in inventory or patents. It was in the brain of its employees.” (page 33)

– “I had learned in the Valley that no more than two people could keep a business secret and that only worked if one of them was dead.” (Page 45 )

– “Under an NDA? I asked. Non-disclosure agreements didn’t usually do much good in the Valley, which was built on loosey-goosey dissemination of intellectual capital, but having one couldn’t hurt. We had a raft of patent applications pending on the technology, but if they stole what we had, we would be defunct by the time we won any lawsuit.” (Page 94)

– “Ron Qi, the inventor [of the technology incorporated in our product] and now head of engineering looked down as if examining the polish on his shoes. The other three around the table, Samantha Maxwell, our Korean-born MIT-educated marketing genius; Ori Mohr, the ex-Israeli paratrooper and kick-ass head of operations, and Bharat Gupta, the CFO, all moved their eyes back to me.” … “I saw Ron, who’d been brought up in the more deferential milieu of Taiwan…” (Page 44) [Immigrants again]

– “I asked the engineers how the tweaking of the product was going, the sales rep what I could do to help them close their big deals, and the bean counters how much work was left to close the books for the latest quarter. What I heard from them was unfiltered by the vice presidents who reported to me. (The business professor) had told me that I could ask any employee anything but I could only tell my direct reports what to do. Managing the others was – who’d’ve thunk of it? – the jobs of their managers. As I popped into offices or cubicles, I was following the footsteps of the Founding Fathers of Silicon Valley, Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard, who advocated MWBA – management by walking around.” (Page 102)

– “Thirty minutes later, I walked into a building named after Robert Noyce, one of the “traitorous eight” whose departure from Shockley Semiconductor loomed as large in Valley history as the exodus from Egypt did in the Bible. One of the founders of both Fairchild Semiconductor and Intel, Noyce was the co-inventor of the microprocessor, the electronic brain that ran everything from cell phones to server farms.” (Page 194)

A few more things on the academic world:

“It seems that the only way for a Stanford professor to win prestige is to start a successful company.

– Americans may not be interested in how the universe is made. I can tell you though, in Silicon Valley, they definitely want to know how money is made.

A researcher at CERN wanted to share information with others physicists. He invented a language to send it around and we ended up with the World Wide Web.

– Of course you would know our wonderful Sir Tim. […] The computer nerds at SLAC in the early 1970s hosted meetings of what they called the Homebrew Computer Club [1]. Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak came.” … “And from that came Apple Computer and the whole PC industry. So you’re saying Silicon Valley wouldn’t be much without the physicists?” (Page 214)

as well as

“I caught sight of a new photo over the desk. His head flanked by two earnest student types. He followed my eyes. “Another sign of my vanity.” Sergey Brin and Larry page developed their search algorithm as Stanford grad students and, of course, started their company to exploit it. Stanford got shares in the venture in return for their ownership of intellectual property.

– And how many millions did that piece of Google add to the university coffers?

– Three hundred and thirty six” (Page 218)

Smasher is certainly not about literature, but it is (really) entertaining; nor does it belong to the category of the mystery masterpieces. Raffel does not have the genius (or experience) of James Ellroy, or even George Pelecanos and Henning Mankell but he is a real pleasure to read, I appreciate his talent, imagination and his interesting description of SV culture, history and dynamics.

[1] Homebrew Computer Club: “One influential event was the publication of Bill Gates’s Open Letter to Hobbyists, which lambasted the early hackers of the time for pirating commercial software programs.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homebrew_Computer_Club. Another site is Memoir of a Homebrew Computer Club Member

[2] Another legacy was his wit—after writing a serious book “The Uses of the University”, Kerr surprised an audience with this riposte–“The three purposes of the University?–To provide sex for the students, sports for the alumni, and parking for the faculty.” From http://content.cdlib.org/view?docId=kt687004sg&chunk.id=d0e21648&brand=calisphere&doc.view=entire_text