Back to my favorite topic, that is Silicon Valley, after a few digressions. I just rediscovered a 2022 paper entitled Systematic analysis of 50 years of Stanford University technology transfer and commercialization. The full paper is available here. As a side comment, this has been motivated by recent articles about Technology Transfer in France and more specifically the study entitled “Étude sur la performance des SATT vis-à-vis d’une sélection d’OTT” (Study on the performance of SATTs vs. a selection of TTOs). Unfortunately, the study does not seem to be public and I could only read comments about it.

I have published a lot about Stanford University. The search engine gives the following here. So I will not go into much detail but just extract what I found interesting not to say surprising. Here it is:

– this is about money, but not only about money.

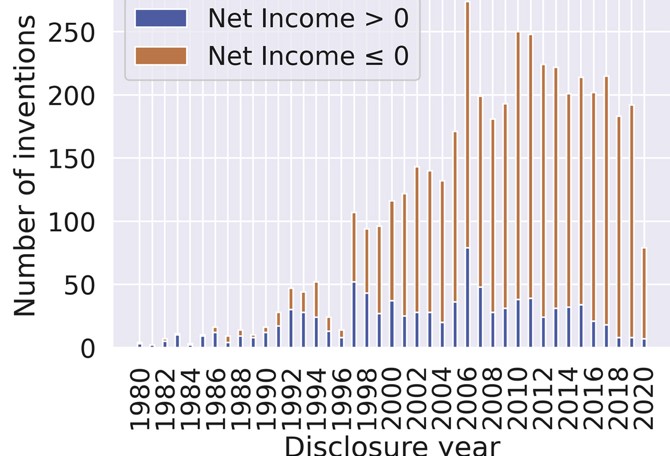

“The total net income of the inventions for all years considered is $581M, and the average net income is $0.13 M. Overall, most inventions have a negative net income, and only 20% of inventions in this dataset have produced positive net income.” Further in the paper “The invention licensing via OTLs represents only one facet of the transfer of technology from university to industry, though it is an important facet. [And] we primarily focus on net income as the outcome metric because it is straightforward to quantify and is a key metric of OTL’s own assessment. However, it is important to note that licensing income does not completely capture impact, and pursuing licensing income is not the ultimate goal of the Stanford OTL.”

Overview of the Stanford inventions data : Number of inventions by year that Stanford’s Office of Technology Licensing marketed. The color of the stacked bar chart indicates whether the cumulative net income (until June 31, 2021) is positive.

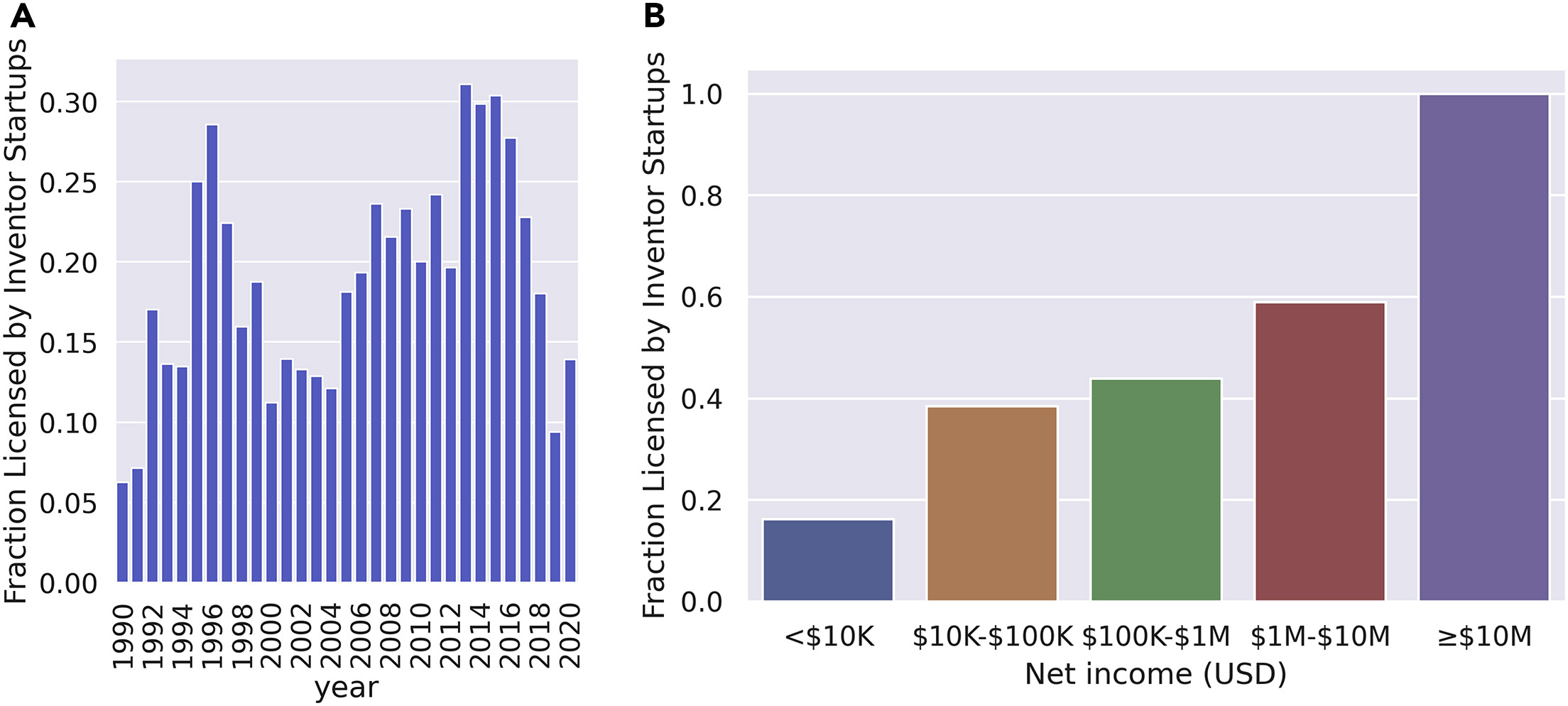

– the most profitable inventions are predominantly licensed by inventors’ own startups.

“Around 20% of the inventions were licensed by the inventor’s own startups, which we refer to as “self-licensing.” Overall, the self-licensing rate increases over time. The interesting peak of the self-licensing rate in 1995–1999 might be related to the dot-com bubble. We also found that inventions with high net income are predominantly self-licensing inventions. For example, all inventions that have generated more than $10 M net income are self-licensed, and the self-licensing rate for the inventions with $1–$10 M net income is 59%. In contrast, the self-licensing rate for inventions with less than $10 K net income is 16%. This finding is consistent with previous research showing that startups with direct connections to the university tend to be more successful than otherwise similar startups.” There is a more general side comment here : “Shane et al. found that new ventures with founders having direct and indirect relationships with venture investors are most likely to receive venture funding.”

Self-licensing (inventions licensed by the inventor’s own startups)

(A) The fraction of inventions licensed by inventor startups over time.

(B) The fraction of inventions in each net income group that the inventors license. The sample sizes for each net income category are: <$10 K: 3,776 inventions; $10–$100 K: 465 inventions; $100 K–$1 M: 212 inventions; $1–$10 M: 56 inventions; ≥$10 M: 5 inventions.

– inventions have involved larger teams over time. There is also an interesting side comment : “Smaller teams have tended to disrupt science and technology with new ideas and opportunities, whereas larger teams have tended to develop existing ones.”

“In addition, we found that the inventions from teams of only first-time inventors have a higher net income than other inventions. This highlights the importance of being open to first-time inventors.” This is correlated with my analysis of serial entrepreneurs, I had found they have a tendency to do worse over time.. See Serial entrepreneurs: are they better?

I will briefly conclude that this is a very interesting new study of Stanford’s contribution to innovation, which confirms well-known things and adds much less known ones. A must-read for experts and “food for thought” for the others!