A friend mentioned this new book about Silicon Valley to me a few days ago and I quote: “The author’s argument is wrong (but it’s pernicious). […] Indeed, entrepreneurship generates excellence and independent-minded people, while [another view – opposition to liberal capitalism] creates a population of people dependent upon the state.”

I’m not sure I agree with my friend: on the one hand, the relationship between collective and individual is a key topic around entrepreneurship. Does a company create value without “outstanding” individuals? The subject is as old as the world. On the other hand, the distribution of this value is a second subject which belongs among other things to the field of taxation and Piketty has clearly shown that, for several decades, the distribution gap has greatly increased in favor of the richest to the detriment of the poorest.

Marianna Mazzucato has shown this imbalance in The Entrepreneurial State, which she finds all the more unfair as she shows the primordial role of the State in upstream funding (education, research, public services in general) which provides a favorable context for the creation of wealth.

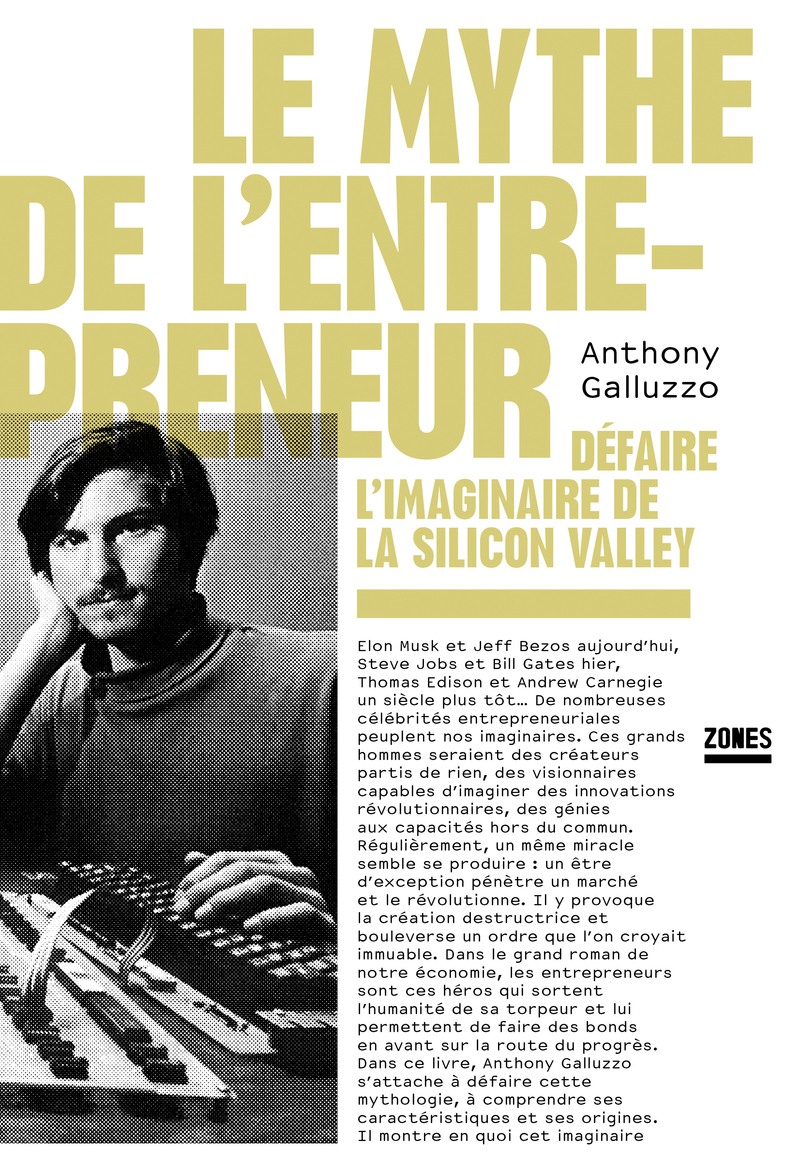

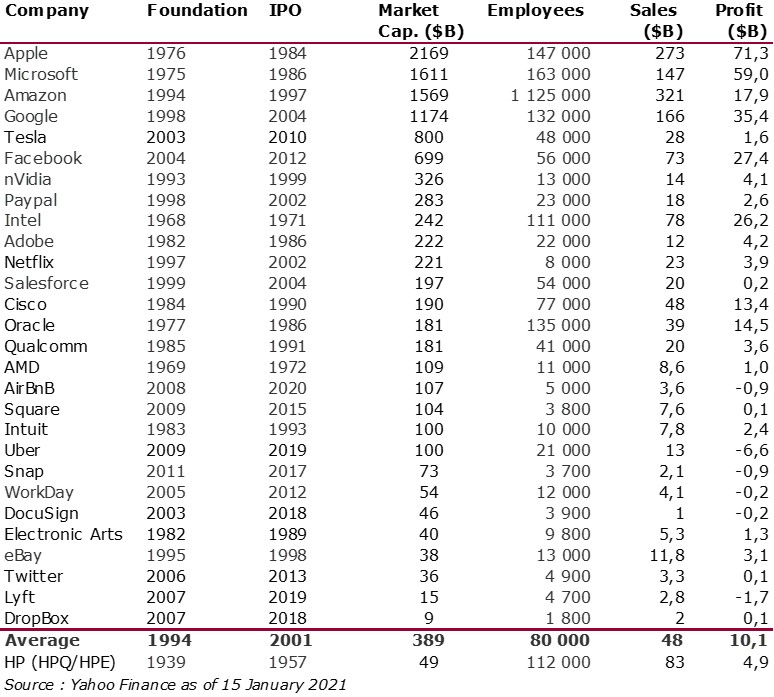

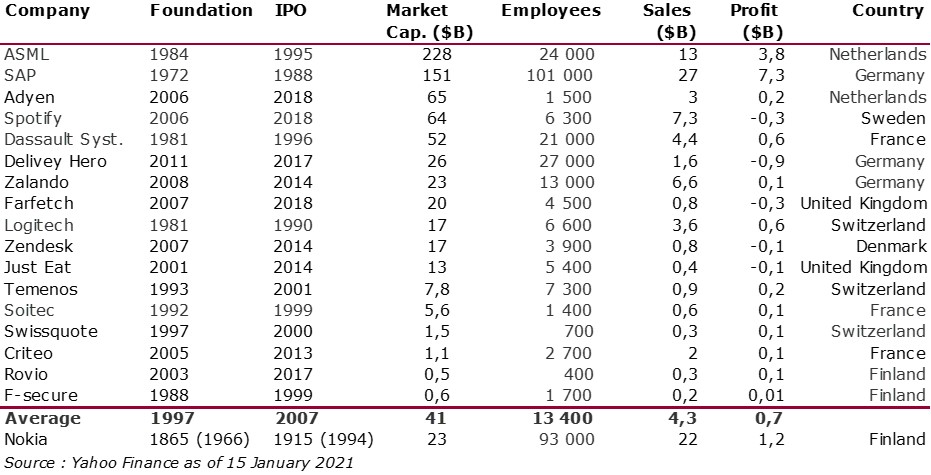

In the beginning of his book, Le mythe de l’entrepreneur – Défaire l’imaginaire de la Silicon Valley (The Myth of the Entrepreneur – Unraveling the Imaginary of Silicon Valley), Anthony Galluzzo explains similar things but it seems different to me. I am only at the beginning and I will see later how closely it joins the criticism introduced above. The author is a specialist in merchant imaginary and the subtitle is convincing, namely that it is necessary to deconstruct the imaginary of this region, based on story-telling around the stars of the region, such as Steve Jobs and Elon Musk (although Elon Musk has largely lost his aura). It shows us that Elisabeth Holmes tried the same approach but succeeded only very partially.

Joseph Schumpeter is quoted extensively in the book at the beginning, in particular it seems to me, for a critique of the role of the entrepreneur and of creative destruction. Galluzzo prefers to use destructive creation to show the chronology of actions. But I didn’t see in the beginning of the book, at least, that Schumpeter adds that capitalism cannot exist without advertising. So without story-telling and imaginary.

This imaginary of Silicon Valley is therefore, I believe, only what allows capitalism to self-develop, to survive, with all the current paradoxes of destructive waste. But behind this imaginary, what is the reality? Galluzzo refuses to oppose entrepreneurs and businessmen. I understand the argument. Creators, stars at least, can make a lot of money. But I don’t know if the main reason is their ability to do business or if they are simply at the origin of a creation that makes it possible to do business. I am neither an economist, nor a historian, nor a sociologist and I find it very difficult to make sense of things, all other things being equal.

Anatomy of the Myth – the Heroic Entrepreneur

So here are a few things that I found interesting in the beginning of the book:

1- The solitary entrepreneur

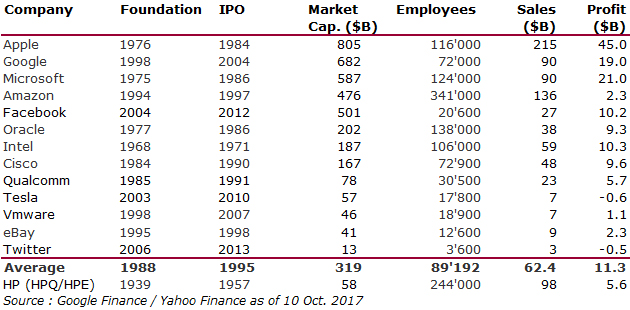

Steve Jobs was not alone and worse is perhaps not critical to the initial success. The story is indeed quite well known while Jobs is seen as the only genius of Apple.

– Steve Wozniak is the real genius (Galluzzo will not like the term) behind the first computers from Apple.

– Steve Jobs is said to have “stolen” [Page 35] many ideas from Xerox to build his machines. The story is known but the term “stealing” is too strong even if many Xerox employees were shocked. Xerox received Apple shares in exchange for this rather unique deal in history.

– “Mike Markkula can be considered the true founder of Apple, the one who transformed a small, insignificant hobbyist operation into a structured and solidly financed start-up. » [Pages 19-20]

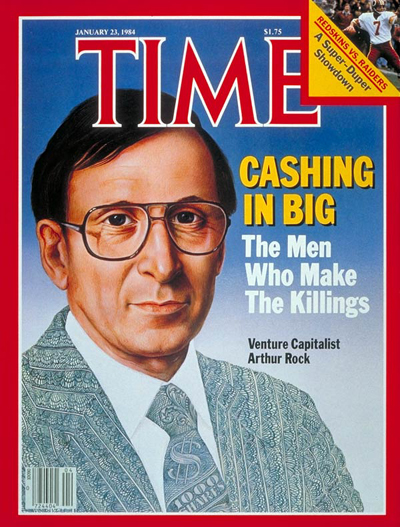

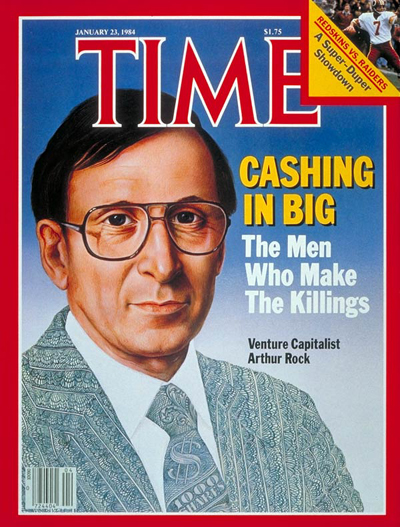

– “Arthur Rock, meanwhile, is one of the most important figures in Silicon Valley, he contributed to the emergence of the largest companies in the region – Fairchild Semiconductor, Intel, then Apple. However, no biography has ever been devoted to him and his wikipedia page is starving”. [Page 20]

I will nuance Galluzzo’s remarks again. Certainly Wozniak, Markkula and Rock have not penetrated the imagination of the general public, but Silicon Valley connoisseurs are not unaware of them and the film Something Ventured (which Galluzzo does not seem to mention in his very rich bibliography) does not forget them at all. And what about this cover of Time Magazine.

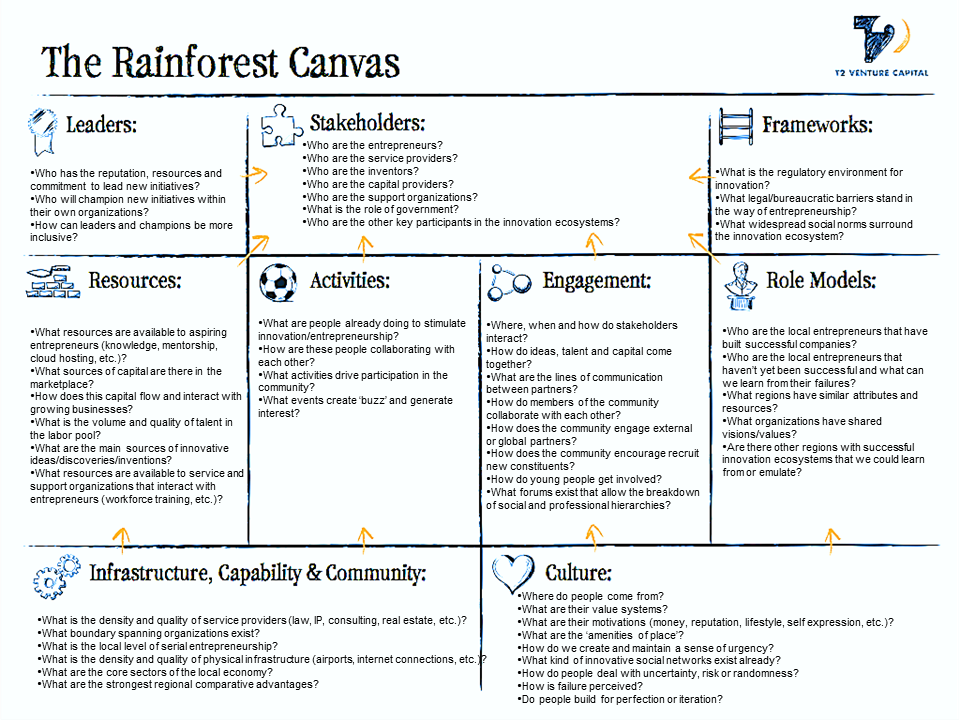

2- The war for talent

“The functioning of the labor market in Silicon Valley, however, shows us a completely different dynamic. The industrial concentration in this region leads to significant personnel movements: an engineer can easily change company, without moving or changing his lifestyle. […] This high degree of labor mobility has been observed since the 1970s, when on average IT professionals only stayed in their jobs for two years [Cf AnnaLee Saxenian’s Regional Advantage]. When circulating like this, employees, even bound by non-disclosure agreements, take with them their experiences and knowledge. The propagation of this tacit knowledge is at the heart of the ecosystem, it allows permanent collective tacit learning. » [Page 45]

Galluzzo gets to the heart of the matter here, which makes Silicon Valley unique. Not so much the concentration of talent, which exists in all developed regions. But the circulation of talent. Almost everything is said!

However, Galluzzo adds a significant nuance that I was less familiar with: “Therefore, problems arise for entrepreneurs relating to what has been called in business jargon the “war for talents”. To carry out his projects, he must succeed in appropriating the most precious commodity there is, the work force of highly qualified engineers.” [Page 46]

Galluzzo then mentions the stock options, the aggressive recruitment but also this: “Another court case illustrates well the issues of employee retention. In the 2000s, several Silicon Valley giants, including Intel, Google and Apple, formed a “wage cartel”, mutually agreeing not to attempt to poach employees. This tacit agreement was intended to eliminate all competition for skilled workers and to limit wage increases.” [Page 47 & see Google, Apple, other tech firms to pay $415M in wage case]

3- The invisibilization of the State

The subject is also known and I mentioned it above. We too often forget the role of the collective in the possibility of favorable conditions and context. But Galluzzo shows that too often there is even a certain hatred of the collective, illustrated by the growing visibility of libertarians. It is also known, Silicon Valley is afraid of unions. Here’s another example I didn’t know:

“I want the people who teach my children to be good enough to be employed in the company I work for, and earn $100,000 a year. Why should they work in a school for $35-40,000 a year if they can get a job here at $100,000? We should hire them and pay them $100,000, but of course the problem is the unions. Unions are the worst thing that has happened to education. Because it is not a meritocracy, but a bureaucracy. »

You have to read the entire excerpt and maybe even the entire interview with Steve Jobs. Excerpts from an Oral History Interview with Steve Jobs. Interviewer: Daniel Morrow, April 20, 1995. Computerworld Smithsonian Awards. We are there in the core American culture and the importance given to competition between individuals rather than to the equality of the members of the collective.

So are there geniuses or not? Is there only Darwinian emergence of talents a posteriori among those who will have survived? I don’t know or I don’t know anymore. Probably something in between. Or maybe it is an act of faith, as long as sociology does not have elements that will allow me to have a more convincing opinion…

To be continued…