(A word of caution: my English is reaching its limits in trying to analyze a demanding book, written in French. I apologize in advance for the very awkward wording…)

So just one day after my article describing Chapter 1 of Emerging Science and Technologies, why so many promises?, here comes an analysis of the second chapter, where the relation to time is analyzed, as well as presentism, futurism and the role of time in the promise system. There is the nice following passage:

Since The New Atlantis, futuristic speculations have accompanied the development of modern science. And in the twentieth century, Jean Perrin has sealed a new alliance between science and hope. But for him, it is science that preceded and provoked hope while now, it is rather hope that drives research. Technosciences reverse, in fact, the order of the questions that was following the three critiques of Kant: “What can I know?” – the issue addressed in Critique of Pure Reason – then the question “What can I do?” – treated in the Critique of Practical Reason – finally the question “What can I expect?” – discussed in the Critique of Judgment. In contrast, in the current scientific policies, one determines what to do and what we can possibly acquire as knowledge by identifying the hopes and promises. (Page 50)

Yet there is a paradox already expressed in the first chapter between futurism with the terms of promise, foresight and prophecy that project us and presentism particularly marked by the memory that freezes the past and transforms the future as a threat that no longer enlightens neither the past nor the present. To the point of talking about a future presentification…

The chapter also deals with the question of the future as a shock, a time “crisis” due to the acceleration. To the feeling of the misunderstanding and helplessness, is added the experience of frustration and stress caused by the accelerated pace of life, the disappointment of a promise related to modernity, where techniques were supposed to save time, to emancipate.

Another confusion: the features of planning and roadmap which are typical of technology projects slipped into research projects where is used the term of production of knowledge, while in research, it is impossible to guarantee a result. But the author shows through two examples, that this development is complex.

In the case of nanotechnology, there has been roadmap with the first two relatively predictable stages of component production followed by a third stage on more speculative systems crowned by a fourth stage which speaks of emergence, and all this by also “neglecting contingency, serendipity and possible bifurcations,” not to predict, but to “linearize the knowledge production”. The roadmap predicts the unexpected by announcing an emergence, combining a reassuring scenario of control which helps in inspiring confidence and with at the same time an emerging scenario, to create dreams. (Pages 55-56)

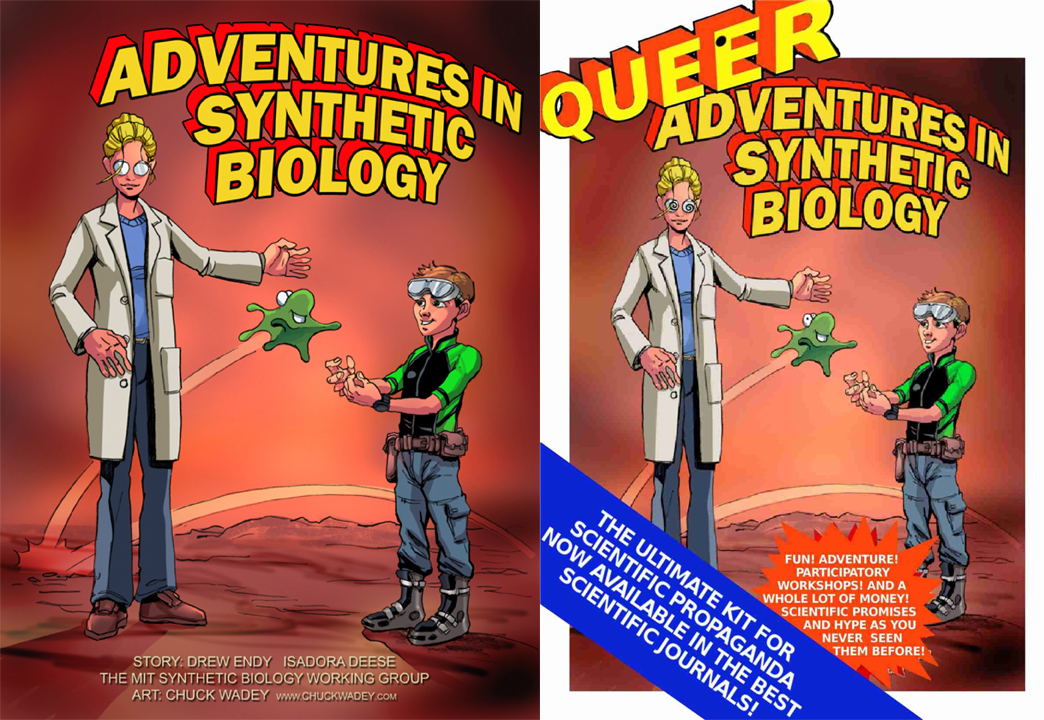

In the case of synthetic biology “despite a clear convergence with nanotechnology,” the rapid development occurs without any roadmap. “A common intention – the design of the living – gathers these research paths.” And it is more to redo the past (“3.6 billion years of genetic code”) than to imagine the future. The future becomes abstract and it comes as proofs of concept. And the author adds that in normal science in the sense of Kuhn, these proofs of concepts would have fallen into oblivion. The paradox is that there is no question of right or wrong, but of designing without any needed functionality.

In the first case, “prediction or forecasting are convened as the indispensable basis for a strategy based on rational choice”, “the future looks to the present. “In the second case, there is the question of “towing the present” and “fleeing out of time.” We unite and mobilize without any necessary aim. The future is virtual, abstract, and devoid of culture and humanity; the life of the augmented human looks more like eternal rest …

Ultimately, the economy of promises remains riveted on the present either by making the future a reference point to guide action in the present, or it is seeking to perpetuate the present.

Chapters three and four are less theoretical, describing on one hand new examples in the field of nanotechnology and on the other, how Moore’s Law became a law when it was initially a prospective vision of progress in semiconductor. Perhaps soon a follow-up about the next chapters…