I have already mentioned Cynthia Fleury on this blog, for example some of her books on Transhumanism is Science Fiction. I just read an interview of her on Telerama, Cynthia Fleury : “Etre courageux, c’est parfois endurer, parfois rompre”. It is so great, I just decided to translate it my way…

Translated from Juliette Cerf. First published on Telerama on 30/08/2015, updated on 01/02/2018.

A philosopher and a psychoanalyst, she insists on how important it is for anyone to build her or his own destiny. It is a condition to protect democracy.

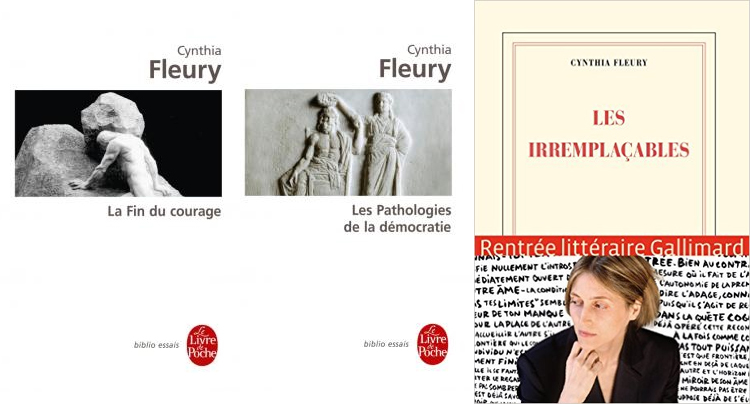

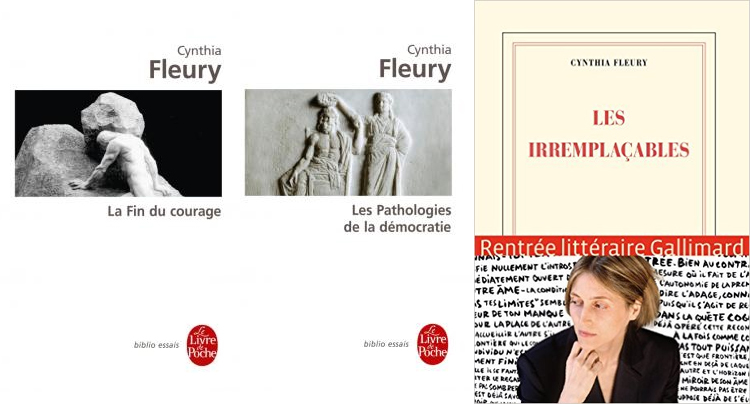

When she was a young doctoral student in philosophy, Cynthia Fleury dreamed of living on a back seat, to devote herself to research and writing, far from the hubbub of the city … Life decided differently and the young woman learnt with time how to live on stage. To be all round. She is now in her early 40s, used to debates and much appreciated by the media for her sharp speech and clear vision. Cynthia Fleury combines many activities: a researcher in political philosophy and a psychoanalyst, she teaches at the American University of Paris. She is a member of the advisory board of the National Ethics Committee, she is also part of Nicolas Hulot Foundation’s think tank for nature and humankind and she is contributor to the Paris medical and psychological emergency unit (Samu). From these different positions of observation, the philosopher watches the drifts and dysfunctions specific to the individual and democracy, at a time when, because of the crisis, everyone withdraws into oneself. How to cure this? How to bring back into the heart of the collective? It is these questions that she addresses in her new essay, Les irremplaçables (The Irreplaceable), which follows her reflection begun in The Pathologies of Democracy and The End of Courage.

Why this title, The Irreplaceable, which sends the reader towards a literary fiction horizon?

Literature is much more poweful than philosophy since it does not produce a doctrinaire, frozen discourse. With a title of a novel, I wanted to evoke the story of the self, the creative power of each. An irreplaceable being is indeed someone committing to a process of individuation, in other words in the construction of her or his own destiny. The book is published in the Blanche collection by Gallimard, which outside of fiction, has always been known for a tradition of philosophical existentialism, with Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, etc. It meant to invest the theme of irreplaceability in an existential and open way, while philosophical theorizing gives a sense of closure. What was at stake was to enter in a dynamic commitment and to create a responsibility for each of us: how does this individual destiny feed a more collective destiny? This is the essential question.

You enroll in the field of political philosophy; democracy is at the center of your thinking.

Yes, and the irreplaceable, at first, were for me the democrats. If I precisely talk about commitment, it’s because I do not live in the illusion of democratic durability. At a time when fundamentalisms, fascisms and populisms proliferate, how can we protect democracy? How do we make sure that individuals are concerned about preserving the rule of law? I realized that any individual who has not worked to develop a fair individuation will not care about preserving democracy. Self-care and concern for the city are intimately linked.

How?

Individuation and democracy work, I think, like a Möbius strip, as the two faces of the same reality. Of course, the rule of law produces the conditions the emergence of an individual, but it does not last if not revitalized, reinvented, reformed by free subjects. If the rule of law remains only a formal reality, it creates huge disappointments that threaten it. It is therefore necessary that it incarnates, and this body of the rule of law is that of the different individuals it gathers. But in recent years, neoliberalism has distorted the rule of law and disintigrated the subjects. The rule of law signs its death sentence: only a well-individuated subject cares about its preservation, and not the alienated subject we meet today.

“The construction of the rule of law is the adventure of this gap between principles and practice.”

You thus evoke the “entropic” drift of contemporary democracies. What is this about?

In thermodynamics, entropy measures the state of disorder of a system: it grows when it evolves towards an increased disorder. However, for thirty years, western democracies experience dynamics of disguise, delirious and unprecedented merchandising, which makes of us interchangeable, replaceable entities, servicing the “growth” idol. Everyone can experience it, whether in the world of finance, consumption, or ecology, through all these phenomena of capture, extreme rationalization, obscene profitability that do not question either their presuppositions nor their expectations. But the expression of democratic entropy is something else, it refers to the internal disorder of democracy, its dysfunctions that are of its very nature. This, Tocqueville has analyzed it perfectly when he defined democracy this way: good principles, theoretically correct and ethically acceptable, which produce perverse effects. The construction of the rule of law is the adventure of this gap between principles and practice.

Could you give an example?

According to Tocqueville, principles change into passions; thus, the passion of the principle of individuation is individualism. The individualistic subject is passionate about himself, self-centered, withdrawn, intoxicated by the intoxication of the self, while the individuated subject sets up a look at the outside world, unfolds and ensures a base, a foundation, which allows her or him to enter into a relationship with what is surrounding. The adventure of irreplaceability, the path to individuation, thus looks like, in many features, that of depersonalization. It’s not about becoming a personality, to put the ego on stage. On the contrary, the challenge is relational: it is a matter of decentering oneself to bind oneself to others, to the world, to meaning.

How to access this individuation?

To give time for oneself is not easily guaranteed. It is a never-ending requirement. To know oneself and to access the quality of being that one owes to the world, the subject must go through three dynamics of knowledge and behavior, which are as many fire tests: imagination, pain and humor. With the first one, the imaginatio vera, the subject produces a true imagination, which is an “agent”, which creates reality. This faculty of soul and heart, at the border of the sensible world and the intellectual world, has an unheard-of power of creation. In this respect, the imaginary, literary space is really the configuration space of reality; it is in no way avoiding reality, as we sometimes think. The imaginary, literary space allows us to verbalize and understand what reality is. The second faculty, pretium doloris, the price of pain, teaches us that the act of thought has a price and that access to the truth can be a painful experience. The trial of Socrates is the very symbol: knowing and knowing oneself mean being at risk.

What about humor?

The vis comica, the comic force, operates an effect of decentering, of distancing which makes the reflexive consciousness arise. The power of humor allows us to grasp the absurdity of reality, as well as our own inadequacy and shortage. While one discovers the absolute inanity, vanity, stupidity of the subject, one manages nevertheless to do something about it. This is essential for the process of individuation, which is primarily a consciousness of shortage, while individualism, infatuated by its pseudo-omnipotence, has totally forgotten that it was short. Individuation is a test of reality, an access to the truth. It is a saying that is obligatory and does not force, and thus renders the subject faithful to herself or himself, irreplaceable. It is a given word, an effort that the individual deploys to bind oneself to the discourse one states.

The brave, at the center of your essay The End of Courage, was already an irreplaceable subject for you?

Yes, irreducible to others, since the brave does not delegate to others the task of doing what is to be done. In The End of Courage, the reconquest of a democratic virtue, I show how ethics of courage are a way to fight against democratic entropy. This virtue, which brings together ethics and politics, is at the same time a tool for protecting the subject and for regulating societies. In the deep intimacy that the brave subject has with his conscience, there is the quality of a public commitment, for others. One can be alone, even against others, when one makes a courageous act, but this gesture always preserves a quality of connection with the community. In everyday life, to be brave is sometimes to endure, sometimes to break up; it may be leaving a job when you are entangled in a perverse situation. On a more historical level, the spectrum goes from political leaders like Nelson Mandela to whistleblowers today.

“There is no democratic project without an educational project”

Individuation, courage: your research intersects with the individual and the collective, psychoanalysis and political philosophy. How did you become a psychoanalyst?

I first started a psychoanalysis at a rather young age, around the age of 17. I did not think about becoming an analyst at all! Then my work as a teacher-researcher in political philosophy focused on the issue of dysfunctions, especially when I wrote Pretium doloris and The Pathologies of Democracy. Reflecting on the suffering at work and on the actions that sometimes accompany it, I have had to collaborate with occupational physicians and clinicians. I wanted to probe more directly the word of the individual. That’s how I became a psychoanalyst. I started my clinical activity in 2007 and have been receiving patients on a regular basis since 2009. I soon realized that the sessions were dedicated to a discourse about reality, society: work, globalization, terrorism, religions, etc. It was necessary to dig to find a discourse about parents, family.

What role does this activity play in your daily life?

I consult every late afternoons as well as weekends. It’s a decisive part of my work today, and it will come even deeper into my writing in the future. I have the feeling that the research I do in the morning or the teaching in the afternoon, in the evening, I hear it formulated in another way, more clinical, as if philosophy suddenly was endowed of a piece of land, while it usually does not. The democratic entropy we were speaking of, I measure its effects every day as a psychoanalyst: individuals feel discouraged, crushed by the rule of law that would be supposed to protect them. To become aware of it is already to extract oneself from it.

Is being a well-publicized philosopher influencing your work as a psychoanalyst?

This necessarily interferes, with very different results depending on the patients. With those who already know you, a phenomenon of transfer precedes you. But the transfer, the emotional projections that the analysed makes on the analyst, is almost magical … Even if this situation requires readjustments, it can be very efficient because it suddenly gives a kind of speed to the analysis, since all the work was done elsewhere. Conversely, there are those who do not know you outside the confessional field of the session and then rediscover you in a field of social and, there, the reactions are diverse. As we are living in an era in need of recognition, it seems to me rather to help; there is also a phenomenon of transfer – my psychoanalyst being recognized, I feel myself caught up in this sphere of recognition. There are misunderstandings, misapprehensions, but it does not really matter, they are always entry points into the analysis. This is very true for young patients under the age of 18, with whom it is always complicated because, if some come by themselves, others do it because their parents want it.

The end of The irreplaceable is devoted to education. Why ?

There is no democratic project without an educational project, both at family level and the social level. As intimate as it is, linked to the irreplaceable love that unites parents and children, education remains the major public enterprise. In this respect, the time of transmission is a very special time, a stretching time. The teachers are well aware of this: you only have two hours, you feel that it is ridiculous, but, in fact, you switch to another space-time which is a symbolic space. There is a click, the beginning of something; attention, empowerment, emancipation, critical awareness. It is in this space that the first fruits of individuation arise. But do not be deceived: it requires work, discipline. Discipline is not submission that transforms us into a sheep, into a link, into a follower: it is a skill, a technical gesture, a way of being, which makes us freer.

Cynthia Fleury in a few dates

1974: Birth in Paris.

2000: PhD in philosophy on the “metaphysics of the imagination”.

2005: Publishes Les Pathologies de la démocratie – the Pathologies of Democracy.

2010: Researcher at the National Museum of Natural History. Publishes La Fin du courage – The End of Courage.

2013: Member of Comité consultatif national d’éthique – Advisory board of the National Ethics Committee.

Wikipedia page (in French).

To read:

Les Irremplaçables, Gallimard, 218 p. €16,90.

La Fin du courage, Le Livre de poche, 192 p. €6,60.