Thanks to an opportunity I got to meet with the Israel Chief Scientist, and the fact I was offered Start-Up Nation at the end of the meeting, let me give you my views on this very interesting book. But first a few things about Israel and innovation.

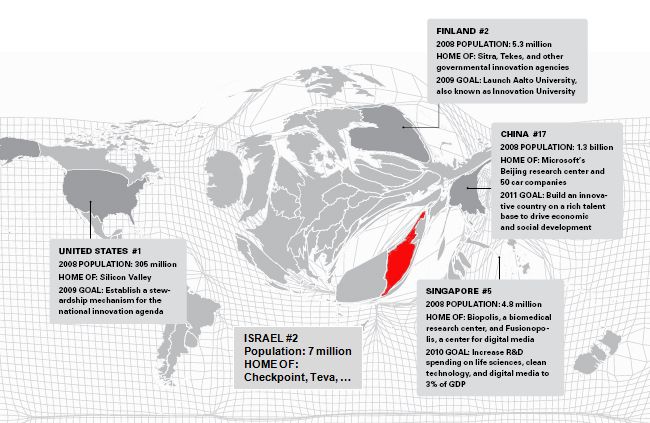

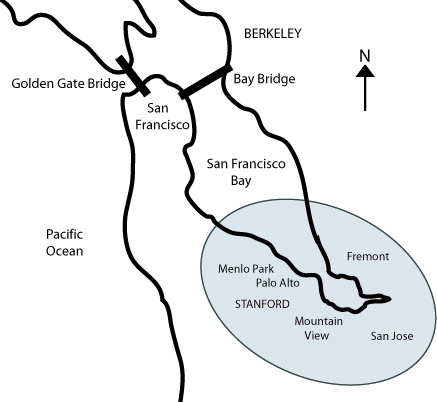

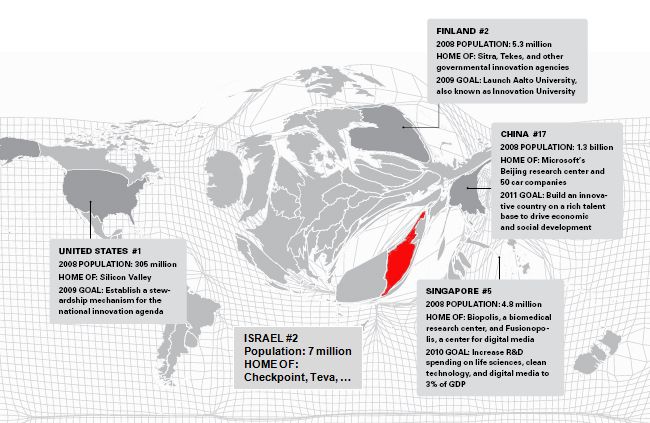

As the map (adapted from John Kao, Harvard and showed at the OCS meeting) indicates, Israel is an innovation superpower. Cisco, Intel, Microsoft, Novartis, Nestle and many others are located there. Check Point is just one of the many start-up success stories. Israel has more start-ups quoted on Nasdaq than Europe and venture capital is very active there. Finally the office of the chief scientist manages and funds the public side of innovation in Israel. All this is perfectly analyzed in the book Start-Up Nation that I have just read.

I thought I knew a lot about Israel, but the book is rich in anecdotes. The history of Israel is well described and innovation was probably a necessity to survive. If there is a point I appreciated less is the importance the authors give to the military. They may be right, that’s not the point, but I thought the topic came too often in the chapters. This remains a great book and a must read for anyone interested in high-tech innovation and entrepreneurship.

I’d like now to quote a few things I liked. It’s not structured at all, but I invite you to read the book!

From the Introduction

Google’s CEO and chairman, Eric Schmidt said that the United States is the number one place in the world for entrepreneurs, but “after the U.S., Israel is the best.” Microsoft’s Steve Ballmer has called Microsoft “an Israeli company as much as an American company” because of the size and centrality of its Israeli teams.”

The authors begin by explaining that adversity and multidimensionality as much as the talent of individuals, are critical: “it is a story not just of talent but of tenacity, of insatiable questioning of authority, of determined informality, combined with a unique attitude toward failure, teamwork, mission, risk, and cross-disciplinary creativity.”

Chapter 1- Persistence

The usual joke Americans need to put, but it is a good one!

Four guys are standing on a street corner . . .

an American, a Russian, a Chinese man, and an Israeli. . . .

A reporter comes up to the group and says to them:

“Excuse me. . . . What’s your opinion on the meat shortage?”

The American says: What’s a shortage?

The Russian says: What’s meat?

The Chinese man says: What’s an opinion?

The Israeli says: What’s “Excuse me”?

—MIKE LEIGH, Two Thousand Years

– No inhibition about challenging the logic behind the way things have been done for years.

– A rude, aggressive culture which tolerates failure.

– Israeli attitude and informality flow also from a cultural tolerance for what some Israelis call “constructive failures” or “intelligent failures.”

– It is critical to distinguish between “a well-planned experiment and a roulette wheel

(During the meeting with the chief scientist, there was a similar argument: “if we have a 5% success rate, we’d better give the responsability to donkeys to choose and if it is 70% success rate, we do not take enough risks”)

– Amos Oz talks about “a culture of doubt and argument, an open-ended game of interpretations, counter-interpretations, reinterpretations, opposing interpretations. From the very beginning of the existence of the Jewish civilization, it was recognized by its argumentativeness.”

Chapter 2- Lesson from the military

– Narrow hierarchy and autonomy gives a lot of responsibility to individuals, authority is discussed

– People are mature earlier.

– No need to wait for order to act.

– “The key for leadership is the soldiers’ confidence in their commander. If you don’t trust him, if you’re not confident in him, you can’t follow him.”

– “If you aren’t even aware that the people in the organization disagree with you, then you are in trouble”

– “Real experience also typically comes with age or maturity. But in Israel, you get experience, perspective, and maturity at a younger age, because the society jams so many transformative experiences into Israelis when they’re barely out of high school. By the time they get to college, their heads are in a different place than those of their American counterparts.”… “The notion that one should accumulate credentials before launching a venture simply does not exist.”

A dense network – the whole country is one degree of separation (Yossi Vardi)

Chapter 5- Order and chaos

– Singapore’s leaders have failed to keep up in a world that puts a high premium on a trio of attributes historically alien to Singapore’s culture: initiative, risk-taking, and agility; in addition to being real experts who can improvise in situations of crisis.

– Innovation is fundamentally an experimental endeavor (improvisation over discipline)

– Learn from mistake with no fear of losing face.

– Nobody learns from someone who is being self defensive

– Fluidity, according to a new school of economists studying key ingredients for entrepreneurialism, is produced when people can cross boundaries, turn societal norms upside down, and agitate in a free-market economy, all to catalyze radical ideas.

Chapter 7 – Immigration

Immigrants are not averse to starting over. They are, by definition, risk takers. A nation of immigrants is a nation of entrepreneurs.—GIDI GRINSTEIN

Sergey Brin spoke in an Israeli high school: “Ladies and gentlemen, girls and boys,” he said in Russian, his choice of language prompting spontaneous applause. “I emigrated from Russia when I was six,” Brin continued. “I went to the United States. Similar to you, I have standard Russian-Jewish parents. My dad is a math professor. They have a certain attitude about studies. And I think I can relate that here, because I was told that your school recently got seven out of the top ten places in a math competition throughout all Israel.” This time the students clapped for their own achievement. “But what I have to say,” Brin continued, cutting through the applause, “is what my father would say—‘What about the other three?

The authors mention the seminal work of AnnaLee Saxenian (Regional advantage, the New Argonauts). As a few examples of Israel tech. diaspora mentioned in the book:

– Dov Frohman – Intel – 1974 – Wikipedia link. Apparently Israel has been the core of Intel innovation in the past decade and Intel is the largest private employer in Israel.

– Michael Laor – Cisco – 1997 – Linkedin profile. Cisco has acquired 9 israeli start-ups since Laor came back (more acquisitions than in any other country except the USA)

– Yoelle Maarek – Google – http://yoelle.com now at Yahoo!

But one should not forget Mirabilis/ICQ (see below) or Check Point. Check Point was established in 1993, by the company’s current Chairman & CEO Gil Shwed, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gil_Shwed at the age of 25, together with two of his friends, Marius Nacht (currently serving as Vice Chairman) and Shlomo Kramer (who left Check Point in 2003 to set up a new company).

Chapter 9 – Yozma

Another member of the tech. diaspora: Orna Berry – PhD USC – Unisys-IBM then Ornet and Gemini then OCS chief… The VC industry was really launched through the Yozma effort as well as Israeli incubators. Gemini was the first Israel fund. See the wikipedia article about venture capital in Israel.

Another quote on start-ups vs. more mature industries: “In aerospace, you can’t be an entrepreneur,” he explained. “The government owns the industry, and the projects are huge. But I learned a lot of technical things there that helped me immensely later on.”

Chapter 12 – Transdisciplinarity

“There’s a multitask mentality here.” The multitasking mentality produces an environment in which job titles—and the compartmentalization that goes along with them—don’t mean much.

– “Combining mathematics, biology, computer science, and organic chemistry at Compugen”

– “Putting this together required an unorthodox combination of engineering skills.”

The term in the United States for this kind of crossover is a mashup. And the term itself has been rapidly morphing and acquiring new meanings. … An even more powerful mashup, in our view, is when innovation is born from the combination of radically different technologies and disciplines. The companies where mashups are most common in Israel are in the medical-device and biotech sectors, where you find wind tunnel engineers and doctors collaborating on a credit card–sized device.

But the authors do not forget to mention that Israel is A country with a motive

Role models

Though Israel was already well into its high-tech swing by then, the ICQ sale was a national phenomenon. It inspired many more Israelis to become entrepreneurs. The founders, after all, were a group of young hippies. Exhibiting the common Israeli response to all forms of success, many figured, If these guys did it, I can do it better. Further, the sale was a source of national pride, like winning a gold medal in the world’s technology Olympics.

“There’s a legitimate way to make a profit because you’re inventing something,” says Erel Margalit “You talk about a way of life—not necessarily about how much money you’re going to make, though it’s obviously also about that.”

“Indeed, what makes the current Israeli blend so powerful is that it is a mashup of the founders’ patriotism, drive, and constant consciousness of scarcity and adversity and the curiosity and restlessness that have deep roots in Israeli and Jewish history. “The greatest contribution of the Jewish people in history is dissatisfaction,” Peres explained.

Again “Not just talent, but tenacity, insatiable questioning of authority, determined informality, unique attitude toward failure, teamwork, mission, risk and cross-disciplinary creativity.”

As a conclusion

“So what is the answer to the central question of this book: What makes Israel so innovative and entrepreneurial? The most obvious explanation lies in a classic cluster of the type Harvard professor Michael Porter has championed, Silicon Valley embodies. It consists of the tight proximity of great universities, large companies, start-ups, and the ecosystem that connects them—including everything from suppliers, an engineering talent pool, and venture capital. Part of this more visible part of the cluster is the role of the military in pumping R&D funds into cutting-edge systems and elite technological units, and the spillover from this substantial investment, both in technologies and human resources, into the civilian economy. … But this outside layer does not fully explain Israel’s success. Singapore has a strong educational system. Korea has conscription and has been facing a massive security threat for its entire existence. Finland, Sweden, Denmark, and Ireland are relatively small countries with advanced technology and excellent infrastructure; they have produced lots of patents and reaped robust economic growth. Some of these countries have grown faster for longer than Israel has and enjoy higher standards of living, but none of them have produced anywhere near the number of start-ups or have attracted similarly high levels of venture capital investments. What’s missing in these other countries is a cultural core built on a rich stew of aggressiveness and team orientation, on isolation and connectedness, and on being small and aiming big. Quantifying that hidden, cultural part of an economy is no easy feat. An unusual combination of cultural attributes. In fact, Israel scores high on egalitarianism, nurturing, and individualism. In Israel, the seemingly contradictory attributes of being both driven and “flat,” both ambitious and collectivist make sense when you throw in the experience that so many Israelis go through in the military. There is no leadership without personal example and without inspiring your team. The secret, then, of Israel’s success is the combination of classic elements of technology clusters with some unique Israeli elements that enhance the skills and experience of individuals, make them work together more effectively as teams, and provide tight and readily available connections within an established and growing community.

If you have arrived here, you were interested enough in this long article. Logically, your next move would be to buy Start-Up Nation!