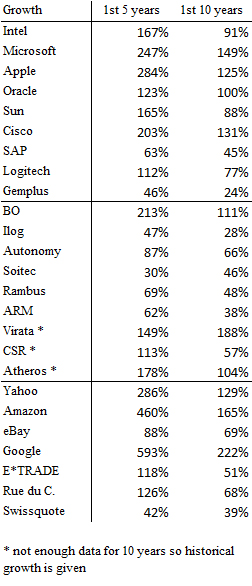

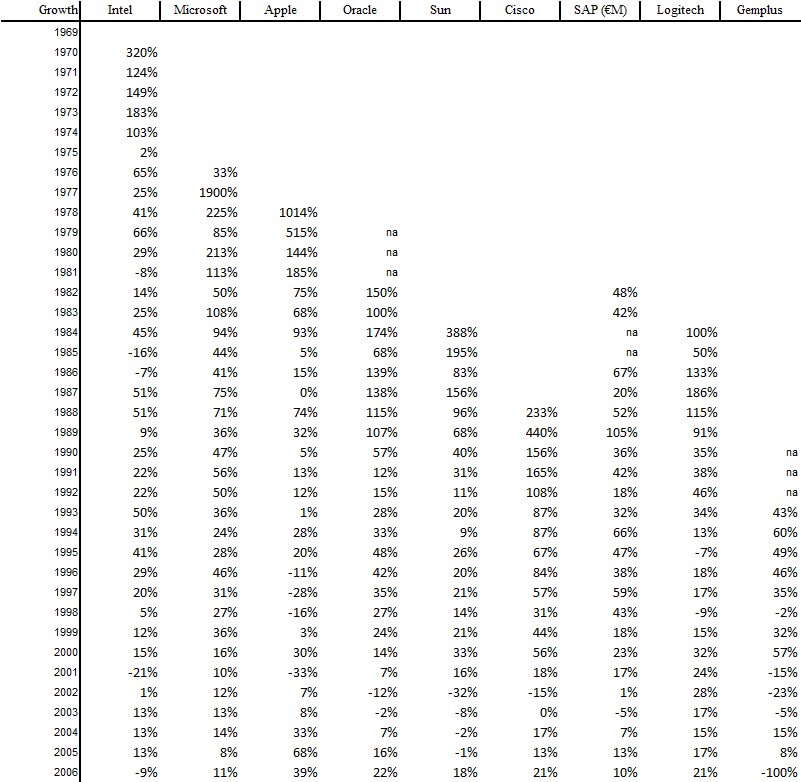

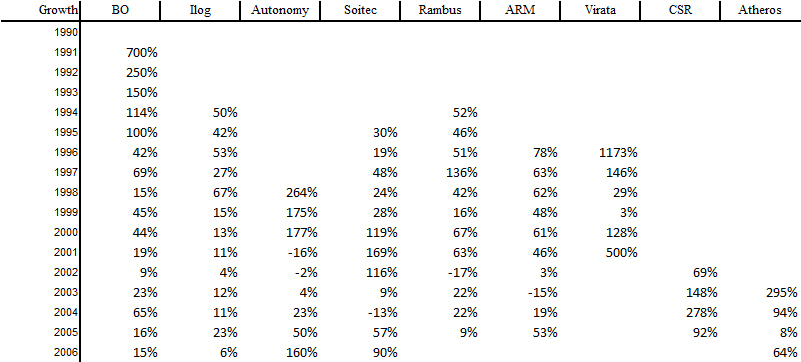

Following my two previous posts on the challenge of growth through Greiner and Google, here is my final contribution thanks a recent WEF report: Global Entrepreneurship and Successful Growth Strategies of Early-Stage Companies

It is a 380-page rich analysis of what it takes to grow and the ecosystem of high-growth companies. I will soon give a few data points on venture capital compiled by the authors, btu I want to focus here on the challenge of growth. Section 2 of the report (The Early-Stage Entrepreneurial Company Journey) focuses on growth accelerators and different growth challenges as well as dark moments and the main lessons from entrepreneurship.

On the growth accelerators (pages 37-38), market opportunity comes first but HR and organization is not too far behind. For the growth challenges (pages 37 and 42), HR is far ahead with market opportunity really behind. Dark moments (pages 37 and 42): it is much more balanced with financing 1st, markets and environement both second, top management 4th.

What is really inresting in the report are less the statistics than the summaries of the inetrviews and let me extract quotes on the dark moments and main lessons on entrepreneurship. they do remind me reading the books Founders at Work, Betting It All and In the Company of Giants. I hope you will appreciate tham as much as I liked putting them here!

Dark moments

There were times I went to bed thinking ‘game’s up’ and when you wake up you find it is not. The many systems challenges in our early years created some very stressful Saturday afternoons that were at times particularly dark moments.” (Betfair)

We thought we were invincible […]. But we didn’t know what was coming and that we were going to face serious trouble[…] All our glory and credibility disappeared. On top of that, my partner left the business. Many of our people in the US left. The company was declared ‘almost irrelevant’ [..]. But we decided we didn’t want to let the company go. I wanted to turn the company around, and the board supported me in that. So we made a number of key moves. (Business Objects)

We needed to convince people that the Internet was a real market. Many potential distributors thought that the Internet was a research network and had no commercial potential. Thus, convincing people to be our first distributors in 1993 to 1994 was by far the biggest challenge. (CheckPoint)

The core issue was a failure to properly plan for the hyper-growth of the site. […] As long as the site was functioning, it was easy to ignore the engineering team’s pleas that the site was running on Band-Aids™ and fumes. […] Unfortunately, those pleas were discounted by members of the senior team until it was too late.” (eBay)

The general worst moments are as you’re running out of cash […] and there’s no term sheet yet […] that was a periodic dark day as I call it. That would come somewhat predictably, but it always and nevertheless hung heavily in the back of my mind. It was one of the few things that could interrupt my sleep. (eSilicon)

There was one particular time in our history, and that was back in the very earliest days of the company when we were still based in New Mexico. One of our first customers was MITS, which was acquired by another company, they stopped paying us and we basically had no income for a year. We were just barely able to hang on, and after that I had a rule that we always had to have enough cash on hand to be able to operate for a full year, even if nobody paid us.

“The first decade it was IBM that almost killed us. I mean they were a great ‘angel’ in a way, but they also almost killed us a few times. We were in a situation long before Windows where we were totally at the behest of IBM. And IBM could have crushed us on many occasions. They had huge demands on us and sucked our resources. We were basically a low cost, outsourced programming sweatshop for IBM. They paid us very little and the only thing we really got from them that turned out to be very lucrative was the right to sell the DOS operating system to other companies. IBM was a large company and we were a small company and every new code release would have to circulate around to all these different divisions, and it was very difficult to keep our technical people motivated to serve the beast, as it were. When we launched Windows, IBM had a competing project, which they were working on with us called OS/2. Previously, IBM had always set the standards. We would provide the technology and their brand recognition and clout in the industry were what really set the standards. When we launched Windows 3.0, that was the first time that we really went out and did it without IBM. We had made an internal decision before that, that whether IBM was with us or not, we were going to launch Windows 3.0. The day before the launch, IBM reluctantly decided to endorse Windows.” (Microsoft)

There were maybe two dark moments. Because it was difficult to get financing, we decided to bootstrap the company as much as we could with our own money and develop the service. That was a challenging period. That was in the spring and summer of 2003. As we started to incur costs in the software developers, we started to run out of money. Some people internal to this project maybe did not believe it would happen. That was one big challenge. (Skype)

“The first dark moment occurred in the summer of 2002. We were running out of money, struggling with a new product and having difficulty penetrating any major customer. We were about to be saved from our misery through an acquisition by our largest competitor, but then they walked away from a definitive acquisition agreement after two months of diligence, during which they had learned all of our secrets and dirty laundry. We could easily have let this situation destroy us, but instead, we took it as a slap-in-the-face and redoubled our efforts and commitment to success. Our founders took this slap personally, and within a year, they had delivered a breakthrough product that was much better than our competitors’ products and allowed us to penetrate Cisco and other key customers. (Netlogic)

“Every company has dark days. In a young company there’s a huge amount of uncertainty. One dark day occurred in the first quarter after we went public. I’m off on a Friday with my wife and my aunt and uncle, and we’re up in Point Reyes –there was no email. So I called into my voicemail, and we had just got notified by one of our customers that they were cancelling a US$ 375,000 development project. We were going to miss our first quarter public. The rest of the day, I’m living in a silent movie. They’re all talking to each other, but I have no idea what’s going on. I’m sitting there spinning in my own mind. I have a knot in my stomach. I am calling into the office every 15 minutes, but there is no news. I came into the office on a Monday morning, after having some time to reflect on it. I said, ‘Well, first we ought to try to go back up to this company that cancelled us and see if we can get them to give us US$ 100,000’. We did a lot of things that quarter, and we figured it out. It was a very dark period. Bad news travels fast and everybody knew we were just hosed. There was no way to fully make it up, and it was awful.” (Veritas Software)

Lessons from entrepreneurship

1. The three Ps are important: Persevere, as you will have many setbacks; be professional in everything you do; and be passionate.

2. Being able to overcome problems is a pivotal skill: After you overcome each problem, you will feel good because you know you are on the right end of that problem and that some other company

will have to handle it.

3. The most undervalued commodity in an entrepreneurial venture is time: You must get things done in a time-efficient way and with minimal distraction.

4. When you get lucky, two things are essential: (a) quickly take advantage of it; and (b) don’t kid yourself it was not luck. Be brutally honest with yourself.”

(Betfair)

1. “The famous lesson from Jim Robbins’ book, Good to Great: ‘Confront the brutal facts but never lose faith in the positive outcome’. This is essential to come through victorious from difficult periods.

2. “Have a clear concept of value and innovation: We started with a great innovative concept that was easy to explain to our customers and we created a brand new market.

3 “Follow a proven entrepreneurial model: a) attract venture capital and have options available for employees to participate in its financial success, b) go global as early as possible, c) find the better market for going public.

4. “Encourage a culture of passion: Adapt quickly to changing circumstances and always be clear about the growth drivers. Cascade goals all the way down in the organization and measure or monitor. Communicate [goals] heavily to your team, so they can lead their own teams.

5. “Take advantage of a global talent pool: it completely changes the fabric of an organization and creates new opportunities.”

(Business Objects)

1.Key leaders in an organization need to be extremely flexible with the ability to get into a completely new field and build a team and strategy to handle it.

2. You never stop being an entrepreneur. At every step you need to build a working and stable infrastructure, and yet still challenge yourself with shaking things up and finding the next new opportunities.

3. In order to succeed, you need an innovative product, a growing marketplace and a great team of people. It is impossible to succeed without the right people, but the other factors are critical to successful growth.

“Whenever you do something, try to do it in the best possible way. If it works, you will establish a precedent that will last for many years. So try to do the right things in the right way the first time.”

(CheckPoint)

One of the things I found really rewarding while working in Silicon Valley is that risk is not only accepted – it’s encouraged. There are tons of experiments going on there all the time. Risk is, in part, how work gets done there. For me, failure only happens when you don’t learn from your experiences. […] Being an entrepreneur is a tough occupation – you have to believe in what you’re doing, even when others are pointing out all the reasons why your idea won’t work. You have to develop a higher risk tolerance and be ready to find the lesson in each idea that doesn’t work.

(eBay)

Point number one is about the motivation for entrepreneurs. On a risk-adjusted present-value basis, no rational person would ever be an entrepreneur if they did it just for the money. Most young entrepreneurs go into this thinking it’s a quick route to the gravy train. And in fact it’s not. It’s more about creativity and self-actualization than it is about compensation.

“Point number two is about having the right venture capital behind you. I encourage people to seek senior partners who hold central power in the VC firm and will be your long-term funding champion.

“Point number three is about the people. A great product or technology misapplied in the market cannot be recovered by a bad management team. But a great management team can take a B product and win by making the right chess moves at the right time.

“Point number four is our three S’s: speed, simplicity and self-confidence. Winning requires speed. Speediness is achieved through simplicity (non-bureaucracy and non-territorialism). Self-confident people feel good about their position in the company and deliver speedy solutions without behaving bureaucratically. A CEO has to ensure that the three S’s are engrained into the company culture.”

(eSilicon)

“One of the key things is that you have to be in the right place at the right time. This isn’t a question of luck. It means that you have to recognize the opportunity early, and go after it with incredible focus and commitment before anyone else does. […]. You also have to be willing to take risks and make mistakes. Nobody should have to worry about being penalized for trying something new and not having it work out. The key is to learn the right lessons from mistakes so you can continue to move forward.”

“Hire the best people you can. One of Microsoft’s strengths was it innovated that way. It spent a lot of time at universities, before that was fashionable, to seek out talent. They hired for high IQs first, and then figured out a way to organize them and make them productive.”

(Microsoft)

1. “Think big and think global. Think differently. And even if people around you don’t believe it, if you really think you have something, you need to believe in your gut feeling and go for it.

2. If you want to go anywhere in life, if you want to pursue your dreams, you have to take risks. Risks involve failures. You cannot be afraid of failure if you want to pursue your dreams.

3. Entrepreneurship is a lifestyle. It is about what defines you. It is about a passion to change and build things. When you look at it this way, it is also about having fun.

4. Once you get going, stay very focused on getting the right people.”

(Skype)

1. “Think beyond the possible and then back off to reality. Just sit down with a piece of paper and look at what you’ve got. I really believe in a very simple SWOT analysis. Then plan, plan, plan. And then adjust.

2. Hire the best people when you can afford it. A great idea can come from anyone in the company.

3. Be prepared to make mistakes and keep innovating.

4. Customer pull is a hundred times more important than a technology push, but nothing is more important than a great engineer.”

(Arm Holdings)

“The first lesson is, don’t start a company just because you want to make money. You start a company because you believe in your idea and are passionate about it. Also, the idea has to be practical, be implementable and solve some real user problem. Then wealth creation will be a by-product.

Second, you should get off the ego trip. Associate yourself with the right people to complement you. Don’t think, just because you are an entrepreneur and the founder, you should be the CEO. You may or may not be CEO material. To succeed, use your strengths rather than assuming you’re strong in every area.

Another important lesson is that you’ve got to attract good people. You can do it if you have a convincing idea that is really attractive. If you don’t have the right idea, or if you’re not passionate enough about it, you can’t attract the right people. You can’t do it alone. Not any one person will have all the expertise.”

(Brocade)

“Personally, I would recommend that any founder and entrepreneur not initiate a venture on one’s own. In my view, the fact that we had a founding team of three – and later four – meant that we could share the psychological load and stress that a fast-growing company brings. While good friends, we largely had independent social lives so we could ‘switch off’ the company from time to time.

(Iona)

The most important lesson is cliché. In technology, the intelligence, creativity, motivation and teamwork of the people ultimately determines the level of success. Providing an environment that attracts, keeps and motivates top employees is an absolute requirement.

(Netlogic)

1. “The most important thing I learned from Silicon Spice is that no matter how sexy or exciting your idea may look, if you want increase your chances for success, then you must actively engage with potential customers early on. They may not become your ultimate customer, but they certainly will teach you about the product and its features and functionality very early on. I would say that’s one of the most critical things to do, even if you have to make a sweetheart deal with them to get their engagement.

2. As an entrepreneur, you have to have the DNA in you to not give up. I could have easily given up on Silicon Spice and moved on to do something else. This drive to succeed at any cost is part of every successful entrepreneur I have worked with. You have to figure out whatever it takes to make a success of the company.

3. The biggest thing I learned from Intel and that I have carried with me since is there is a discipline about focus and execution. You have to focus on very crisply defined deliverables. You can’t just clutter people with 100 things. You have to distil them down to one or two. However, you have to be very careful. You can’t dump all of Intel’s culture into a start-up, either. But there are elements of the Intel culture that, when brought in a suitable manner, can help a start-up become far more efficient and successful.”

(SiliconSpice)

“Number one: The most important thing is the right product, in the right market, at the right time.

“Number two: The greatest flaw that the entrepreneurial character has is that they get excited about their own ideas and they start filtering with a confirmation bias. What you want to do is open all portals to new information.

“Number three: One of the hardest things for me is this very profound ambiguity you experience. You have a vision of what you want to do, who you are and what defines you, but along the way, you have to do all these opportunistic and pragmatic things, which draw you in different directions and you just never see that original vision. You have to be able to do things that betray that original vision for the good reasons along the way. Sometimes you have to just abandon it and move onto the next thing because it’s the better thing to do. For me, that turned out to be a very hard thing to do.

“Number four: If you don’t listen to your board, you may or may not get fired. But if you listen to your board and investors, you’re guaranteed to get fired. I believe you have to take leadership. And if I sit and think about the business 24 by seven, and when you run a company – it’s the only thing in your life, it’s 24 by 7 – guys that show up once a month or quarter, and kind of flirt with this thing, are simply not qualified to have a better opinion. And investors who buy your stock and sell it ten minutes later, are even less qualified to have a better opinion – although that doesn’t prevent them from having opinions. You have to do what you believe is the right thing for the company and you have to put your job on the line to do it sometimes, and that’s just part of what it is. Sometimes you win, sometimes you lose.”

(Veritas Sofwtare)