Following my part 1 about In the Plex, here is part 2 and though I will come back with the topic in part 3 let me begin with this: Googlers love jokes and in particular April Fool. Nobody knew how successful and profitable Google had been for some years…

The hiding ended on April 1, 2004. As a consequence of going public, the company was required to share its internal information with the bankers who would potentially handle the IPO. Google’s finance people had gathered the bankers in its headquarters, then located in Mountain View. On the eve of the meeting, chief financial officer George Reyes and Lise Buyer, the director of business optimization, came up with a plan to reveal the secret Google style. Opening the meeting, Reyes welcomed them. Since the bankers had taken a big gamble by signing on without seeing the bottom line, he said, he’d go straight to the numbers. Then he put up slides with some figures. “You could hear a pin drop,” Buyer would later recall. The slides indicated that Google was indeed making pretty good profits. Not earthshaking but more than respectable, especially for an Internet business offering a free service supported only by ads. The bankers listened politely, but you could tell that they’d heard chatter that things had been, well, better than good, and they were apparently doing some mental recalculations.

Then Reyes told the bankers he was sorry, but he’d mistakenly put up the wrong slide. Could he display the real numbers? A balance sheet appeared with more than double the revenues and profits on the previous slide. It exceeded even the wildest expectations. April fool! “George was flawless,” says Buyer. “It was a beautiful moment.” [Page 70]

What’s a business plan?

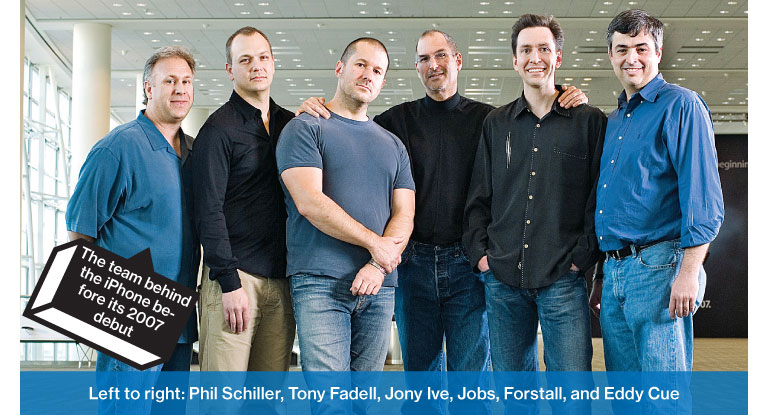

The Google founders had not been that much focused on the business side… Salar Kamanagar would be a very unusual hire:

Kamangar more than compensated for his lack of experience with quiet determination. Though he appeared placid and self-contained— and loathed the spotlight—he had a steely, gnawing resolve. […] Kamangar made a short list of companies he might like to work for—brand-new start-ups that might take a chance on someone like him—and because, like many Stanford students, he had been playing with an early version of Google, he put it on his list. One day in March 1999 he saw in the Stanford Daily that Google was recruiting. He went to the Tresidder student center and found Sergey Brin in a small booth. “Unlike everyone else I’d talked to, he wasn’t using jargon. He had a very clear, very ambitious, grand—in some ways grandiose—vision for what Google could become,” Kamangar would recall. But Brin was not interested in hiring him. Kamangar was a biology major, not an engineer. Even at that stage, the Google preference was for computer science majors. Kamangar kept pressing. “He would walk in every day and say, ‘I want to work for free,’” says investor Ram Shriram, who was taking a day off from Amazon every week to help protect his investment in Google. Brin finally agreed to take him on part-time to do things that engineers couldn’t be bothered with, such as drawing up a business plan. “Neither founder had any interest in that,” says Shriram, “They said, ‘Yeah, we need money, but we’re not really interested in spending too much time on that. What’s a business plan?’” Whatever it was, Google needed one. Its original million-dollar funding had been granted solely on the basis of Google’s technology. But the company was already struggling to pay for equipment—its servers were overwhelmed by new users—and Brin and Page needed full coffers to finance their ambitious hiring plans. Venture capital could provide that. But they’d have to make a credible case that Google could one day be profitable.

Kamangar became the point man in one of the weirder VC rounds in Silicon Valley’s history. Shriram helped him out, but Salar had a remarkable degree of responsibility. He wrote the slides for the presentations, crunched numbers for the valuation, and, of course, drew up the business plan. Though hired as a part-timer, he went fulltime two weeks later, dropping his pursuit of a second degree at Stanford. “It was ten times more exciting than what I was doing at school,” he says of Google. [Pages 71-72]

“How big do you think this can be?”

[John Doerr, from Kleiner Perkins]’d seen plenty of smart nerds with good ideas, and was more than happy, on the recommendation of Andy Bechtolsheim, to see two more. Google’s idea, presented with Kamangar’s slides, was compelling. And its founders seemed straight out of the mold of previous winners from Stanford. The meeting was just ending when Doerr asked a final question: “How big do you think this can be?”

“Ten billion,” said Larry Page. Doerr just about fell off his chair. Surely, he replied to Page, you can’t be expecting a market cap of $10 billion. Doerr had already made a silent calculation that Google’s optimal market cap—the eventual value of the entire company—could go maybe as high as one billion dollars. “Oh, I’m very serious,” said Page. “And I don’t mean market cap. I mean revenues.”

More than a decade after that meeting, Doerr would still marvel at the conversation. “I didn’t think the guy could do it, but I was impressed,” he says. “It had to do with the tone of voice. He wasn’t saying this to impress me or himself. This is what he believed. This was Larry’s ambition, in a very thoughtful, considered way.” [Page 73]

A business or three?

The post-VC business plan anticipated three streams of revenues: Google would license search technology to other websites; it would sell a hardware product that would allow companies to search their own operations very quickly, called “Google Quick Search Box”; and it would sell ads.

Brin and Page themselves had made the very first licensing deal, with a company called Red Hat, a software company that distributed a version of the free Linux operating system. It earned Google around $20,000. [Page 78]

But advertising was far from obvious…

But they had no idea what a Google ad should be. Some at Google—including the director of technology, Craig Silverstein—thought that the whole effort was a distraction and that Google should outsource its ad system to some company more accustomed to waddling in the muck of Mammon. “I was like, ‘We’re not an advertising company, we’re a search company—let someone else worry about the advertising,’” says Silverstein. “It was good they did not take my advice.” [Page 78]

Susan Wojcicki later admitted the real problem: “No one clicked on the ads.” But she felt that the experiment was a great success. “It was incredible that we were going to build an ad system at all. What, we didn’t have enough to do with search? Now we’re asking our engineers, ‘Can you develop subsecond delivery times in every language in the world for every specific keyword?’ It was impressive that they actually did it.”

One contingent unimpressed at this point was Google’s investors. By the time of the Amazon affiliate bust in January 2001, it was almost two years after the $25 million investment, and the company was yet to make any money from the 70 million daily searches on its site. One angel, David Cheriton, was joking to friends that all he’d gotten from his six-figure Google investment was a T-shirt—“the world’s most expensive T-shirt.” To the money people on Google’s board, the problem was no joking matter. [Page 79]

So they hired a full-time CEO as the founders needed “adult supervision”.

From the start, Schmidt adopted a public stance toward the founders of unfettered admiration, a position he carefully maintained thereafter. “I fairly quickly figured out these guys are good at what they do,” he told me in early 2002. “Sergey is the soul and the conscience of the business. He’s a showman who cares deeply about the culture, the one who talks more, with a bit of Johnny Carson. Larry is the brilliant inventor, the Edison. Every day I am thankful I accepted this job offer.”

His anecdotes about disagreements with Sergey and Larry followed a consistent storyline: Schmidt expresses a tradition-bound preconception. The young men who, technically at least, report to him, reject the idea and demand that Google pursue an audacious, seemingly absurd alternative. The punch line? “And of course they were right,” Schmidt would say. What had seemed crazy was actually a canny assessment of how things worked in the new Internet-based economy! […]

That deference would prove a winning strategy, even though for a couple of years there were serious adjustment problems, because the founders clearly suspected that they would have done just fine on their own. Kordestani remembers that as Schmidt’s arrival was impending, both founders expressed their anxiety to him. Ostensibly, the issue concerned the titles each of the founders would use to describe his respective role. On a deeper level Sergey was troubled, says Kordestani, because “he was hiring his own boss, in a way, knowing he wants to be the boss.” Brin took the title president of technology.

Larry was even more troubled. Kordestani had to assure Page that he was still essential and Google would fail without him. Kordestani also reminded Page that he would no longer have to perform tasks that he didn’t enjoy, such as dealing with Wall Street and talking to customers. Page wound up describing himself as president of products.

As late as 2002, the founders still sounded bitter when explaining why Schmidt was hired. “Basically, we needed adult supervision,” said Brin, adding that their VC investors “feel more comfortable with us now —what do they think two hooligans are going to do with their millions?” The transition was rocky, but as the years went by, Page and Brin seemed to genuinely appreciate Schmidt’s contribution. Page would come to describe the CEO’s hiring as “brilliant.” [Page 81]

Indeed three ad models.

But contempt for traditional advertising permeated Google from the top down. In their original academic paper about Google, Page and Brin had devoted an appendix to the evils of conventional advertising. The founders weren’t sure what their ads would be but were adamant that they somehow be different. […] Nonetheless, the early Google ads worked like traditional ones in one key aspect: the advertiser was billed according to how many people viewed the ad. This CPM (cost per thousand) model was the basis of almost all ad markets. […] While Google expected to make most of its money from licensing, Armstrong was told, advertising might one day account for as much as 10 to 15 percent of its revenue. [Page 84]

Finally Google created AdWords Select and AdSense in addition to the classical AdWords Premium. And surprise, surprise…

The dicier challenge was getting skeptical customers of the original AdWords to leave a system they were happy with to try this complicated new one. On January 24, 2002, Google tested AdWords Select by offering it to selected advertisers. […] From that point on, revenue from the right-hand side of Google’s search results page—which had previously constituted only 10 to 15 percent of Google’s ad take, with the bulk coming from the direct sales of premium ads—began rising. […] In any case, Google was reaping rewards, and 2002 was its first profitable year. “That’s really satisfying,” Brin said at the time. “Honestly, when we were still in the dot-com boom days, I felt like a schmuck. I had an Internet start-up—so did everybody else. It was unprofitable, like everybody else’s, and how hard is that? But when we became profitable, I felt like we had built a real business.”

Best of all was that Google, against all odds, was making that profit without surrendering its ideals. “Do you know the most common feedback, honestly?” Brin asked. “It’s ‘What ads’? People either haven’t done searches that bring them up or haven’t noticed them. Or the third possibility is that they brought up the ads and they did notice them and they forgot about them, which I think is the most likely scenario.”

[…] Page said in 2002. “Every month we make more money than the last one.” The only slight regret? They never got those PhDs.

“I’ve been meaning to,” said Sergey.

“Maybe someday,” said Larry.

“My mom keeps asking,” said Sergey.

Larry frowned. “My mom doesn’t ask me anymore.”

[Pages 93-94]

Still automatic advertising may be risky…

The only hitch in the program was the risk that the ads Google placed on a website would be inappropriate or even offensive. When human beings created an ad for a publication, they took care to avoid situations where the combination of a certain ad with a certain type of article would produce a tasteless match that would appall readers and win no business for the advertisers. Google’s algorithms weren’t so sensitive. “The editors would get freaked out,” says Liebman. Some of the unintentionally offensive matches became classics. Liebman would cite an ad that ran alongside a gory murder story in the New York Post: someone had chopped up a body and stuffed it in a garbage bag. Alongside this gruesome text was a Google ad for plastic bags. “We didn’t foresee that there were times when you don’t want to target ads to the content,” says Georges Harik. “We would analyze a page about a plane crash and happily place an ad for airline tickets. I think we rapidly discovered that this was a bad idea.” Google engineers started working on ways to mitigate this problem, but it would never be totally eliminated. It was just too hard for an algorithm trained to discover matches between articles and ads to exercise human good taste. In 2008, a story about the Mumbai attacks headlined “Terrorists kill the man who gave them water” was accompanied by an ad that read “Terrorism: Pursue a certificate in terrorism 100% online. Enroll today. Ads by Google.” An account of massive food poisoning at an Olive Garden restaurant in Los Angeles was accompanied by a coupon offering a “FREE Dinner for Two at Olive Garden.” [Page 105]

A really amazing business…

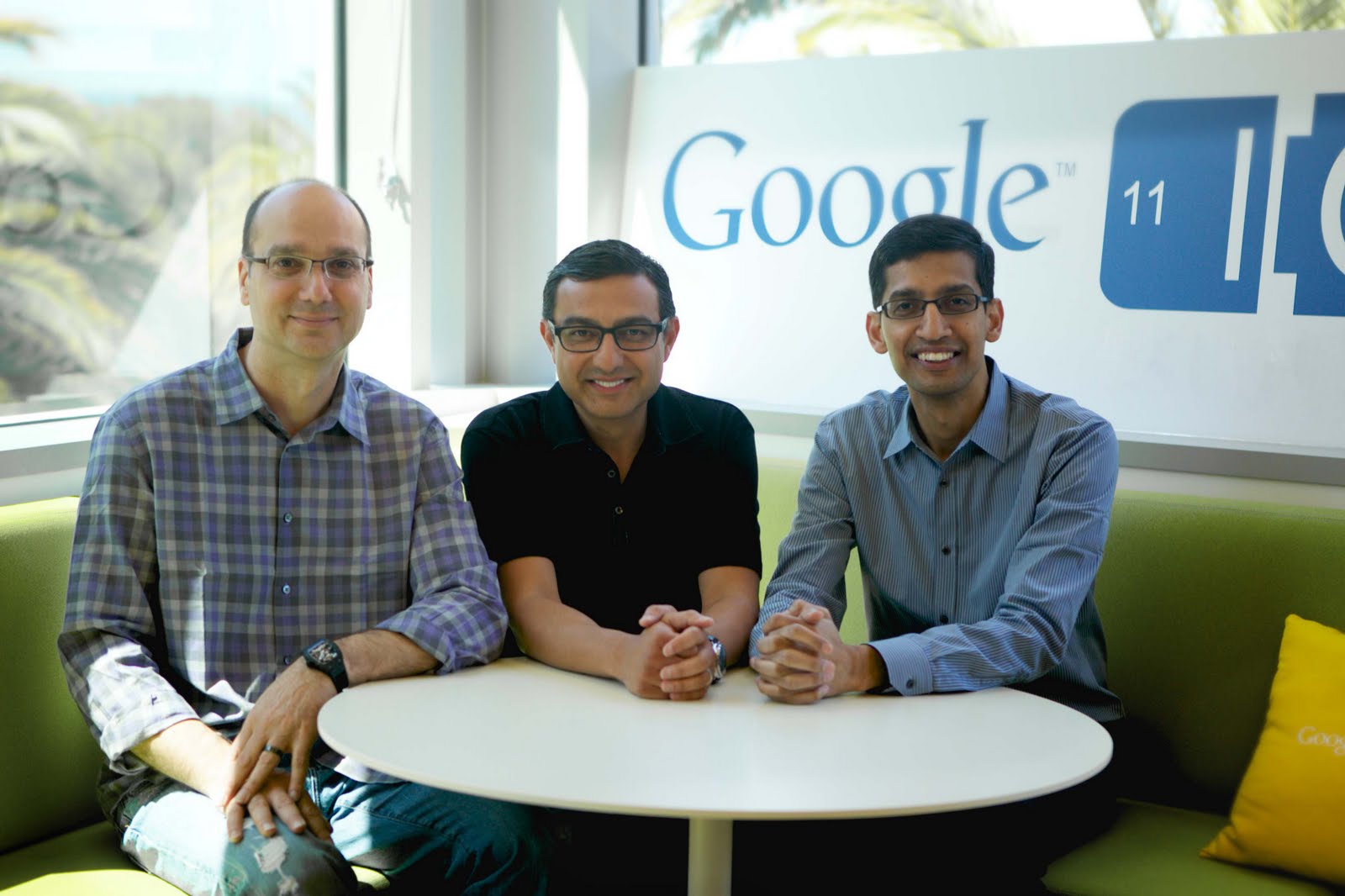

When someone clicked on an AdSense ad, the money paid by the advertiser was split between Google and the publisher whose site hosted the ad. According to Rajaram, the original thought was to split the money down the middle—Google would take half and the AdSense publisher would take the other half. But Brin thought that such a split gave too much to Google. The idea was to build the program for the long run, and if Google made it clear that it was taking half the money, a competitor might undercut the program by giving 80 or even 90 percent of the fee to the publisher. So Google decided to give the majority of the money to the publisher. Then Susan Wojcicki came up with an idea that some might find strange: What if we don’t reveal the revenue share percentage with the publisher? That way Google wouldn’t have to worry about a competitor boasting a better split. [Page 106] Which they did.

“It was one of the single biggest painful things for me,” says Rajaram. “On every panel I went to for the first year, I would get questions about why isn’t Google sharing the revenue split and why isn’t Google being transparent. People said we were doing it because we weren’t generous. But quite to the contrary, we were being generous. We just didn’t want our competitors to tell publishers that they were offering a better revenue share.” (In May 2010, Google finally revealed the split. “In the spirit of greater transparency,” Google reported that of the money received from advertisers on AdSense for content, 68 percent went to the publishers whose pages hosted the ads. Google kept the other 32 percent. That was close to the proportions that participants and analysts had long assumed. Google’s belated announcement only raised more questions as to why it had been a secret in the first place.) [Page 106]

Later in the year, AdSense achieved a milestone in its run rate— $1 million a day. […]While AdSense was a great success, the bulk of Google’s revenues came from AdWords. Eric Veach and Salar Kamangar’s auctionbased AdWords Select product had first been thought of as a supplement to the more traditional, impression-based ads in the premium program, which was now called AdWords Premium. But it was working so well that Google would sometimes allow its auction-based ads to break out of their side-of-the-page ghetto and leapfrog to the premium zone sitting on top of the search results. If Google felt that the outcome would raise more revenue, a select ad would “trump” a premium ad and knock it out of that coveted position. As more and more auction-based ads trumped the hand-sold premium ads, Kamangar argued that Google should entirely end the practice of selling premium ads by a sales force that set prices and charged by impression. He set up a project, code-named D4, to implement the idea. Most Googlers called the plan Premium Sunset. […] Eric Veach believed that the data showed that the auction-based, pay-per-click model was actually better for everybody. The key was the ad quality, which made sure that ads would appear before sympathetic eyeballs. He did a close analysis and concluded that ads bought through AdWords Select performed better. He also uncovered hard proof that some premium advertisers were paying way too little for some valuable keywords. […]Nonetheless, the move would be painful. It meant giving up campaigns that were selling for hundreds of thousands of dollars, all for the unproven possibility that the auction process would generate even bigger sums. “We were doing $300 million in CPM ads and now were going to turn this other model on and cannibalize that revenue,” [Page 110]

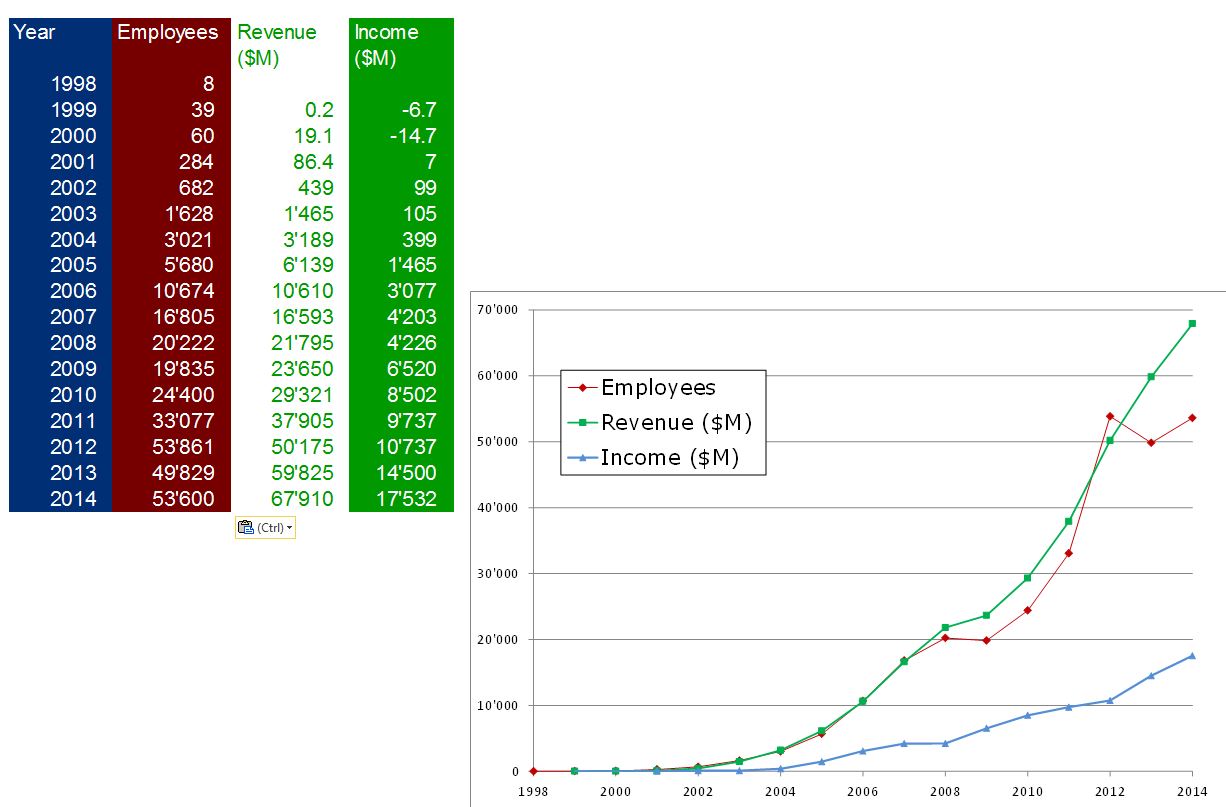

And here is the history of Google growth…