Serial entrepreneur is a buzz word. I have never been convinced by the link between serial entrepreneur and success. I even made an analysis for the ones linked to Stanford University (check Serial entrepreneurs: are they better?). But from time to time, you see such amazing and rare success stories.

Andy Bechtolsheim (left) and David Cheriton (right) [with Arista’s co-founder, Ken Duda).

Andy Bechtolsheim‘s is a Silicon Valley icon. In 1982, he co-founded Sun Microsystems. Born in Germany in 1995, he moved to the USA at age 20 for his master at CMU. He moved to Silicon Vallley to work at Intel but ended up at Stanford for his PhD. Sun came thereafter. He stayed there until 1995…

David Cheriton is a Stanford professor. Born in 1951, he got his BS from UBC and his PhD from the University of Waterloo. He moved to Stanford in 1981. I am not sure how they met, but they co-founded Granite Systems in 1995. A year later, it was bought by Cisco for $220M. Bechtolsheim stayed with Cisco until 2003. Cheriton is still a Stanford professor. Two years later, they met with two unknown Stanford students, Larry Page and Sergei Brin. Both invested $100’000 each in their start-up, but this is another story…

In February 2001, they co-founded another networking start-up, Kealia. In April 2004, “Sun issued an aggregate of approximately 20,000,000 shares of common stock (including assumed options) in exchange for all outstanding stock and options of Kealia” (Newswire reference). At that time, Sun’s share was worth about $4, so it would have been an $80M acquisition. That same year, Google went public (on August 19) at $85/share. They had received 1’600’000 shares for their $100k investment (i.e. $0.0625 per share, a multiple of 1’360 and with a six month lock-up, the share value more than doubled…) The Kealia success is all but relative…

Granite might have had a logo, but I could not find it on the web. Kealia was apparently always in stealth mode. No logo available either

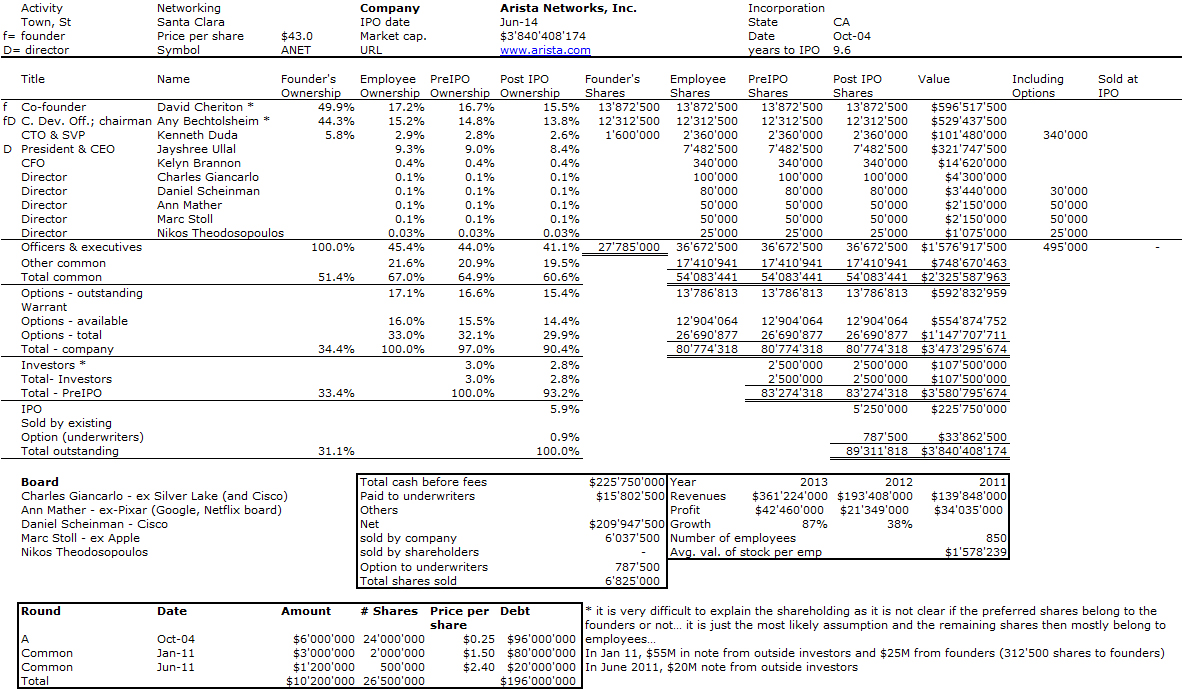

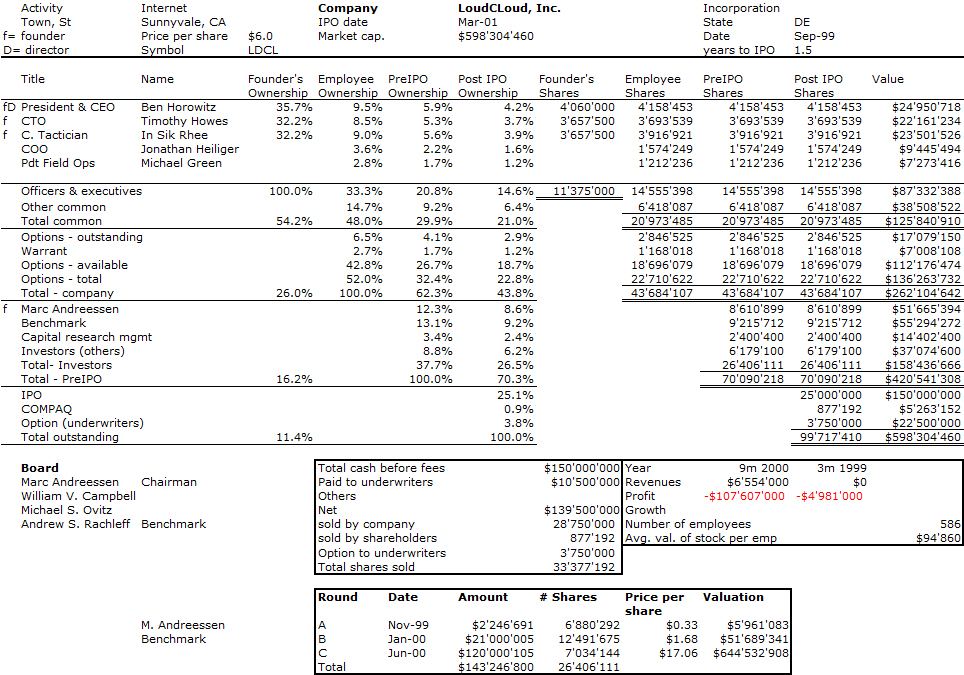

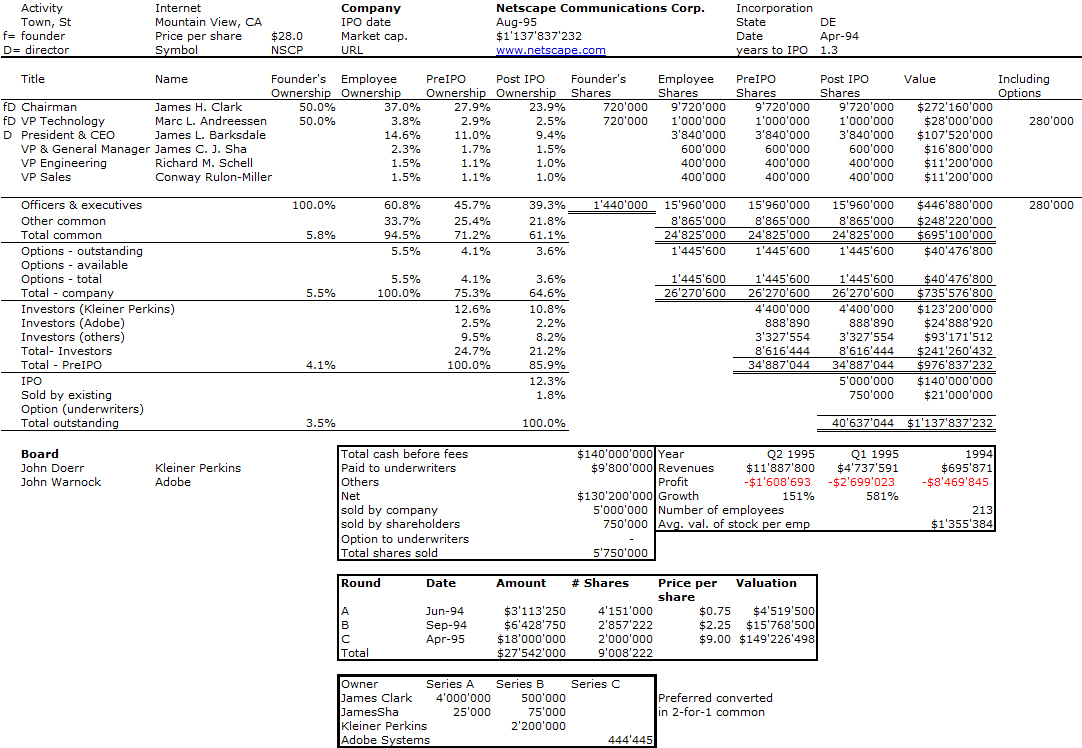

But it did not stop them. In October 2004, they co-founded Arista Networks. The name at the time was Arastra. The company just went public which is the motivation for this post. My usual cap. table follows. And because they made so much money, the two serial entrepreneurs nearly funded it entirely… Not the smallest success of all!

PS: Are Cheriton and bechtolsheim good friends? I have not clue, but the Arista IPO document mentions a litigation:

On April 4, 2014, Optumsoft filed a lawsuit against us in the Superior Court of California, Santa Clara County titled Optumsoft, Inc. v. Arista Networks, Inc., in which it asserts (i) ownership of certain components of our EOS network operating system pursuant to the terms of a 2004 agreement between the companies, and (ii) breaches of certain confidentiality and use restrictions in that agreement. Under the terms of the 2004 agreement, Optumsoft provided us with a non-exclusive, irrevocable, royalty-free license to software delivered by Optumsoft comprising a software tool used to develop certain components of EOS and a runtime library that is incorporated into EOS. The 2004 agreement places certain restrictions on our use and disclosure of the Optumsoft software and gives Optumsoft ownership of improvements, modifications and corrections to, and derivative works of, the Optumsoft software that we develop.

In its lawsuit, Optumsoft has asked the Court to order us to (i) give Optumsoft copies of certain components of our software for evaluation by Optumsoft, (ii) cease all conduct constituting the alleged confidentiality and use restriction breaches, (iii) secure the return or deletion of Optumsoft’s alleged intellectual property provided to third parties, including our customers, (iv) assign ownership to Optumsoft of Optumsoft’s alleged intellectual property currently owned by us, and (v) pay Optumsoft’s alleged damages, attorney’s fees, and costs of the lawsuit. David Cheriton, one of our founders and a former member of our board of directors who resigned from our board of directors on March 1, 2014 and has no continuing role with us, is a founder and, we believe, the largest stockholder and director of Optumsoft. The 2010 David R. Cheriton Irrevocable Trust dtd July 27, 2010, a trust for the benefit of the minor children of Mr. Cheriton, is our largest stockholder.

Optumsoft has identified in confidential filings certain software components it claims to own, which are generally applicable tools and utility subroutines and not networking specific code. We cannot assure which software components Optumsoft may ultimately claim to own in the litigation or whether such claimed components are material.

On April 14, 2014, we filed a cross-complaint against Optumsoft, in which we assert our ownership of the software components at issue and our interpretation of the 2004 agreement. Among other things, we assert that the language of the 2004 agreement and the parties’ long course of conduct support our ownership of the disputed software components. We ask the Court to declare our ownership of those software components, all similarly-situated software components developed in the future and all related intellectual property. We also assert that, even if we are found not to own any particular components at issue, such components are licensed to us under the terms of the 2004 agreement. However, there can be no assurance that our assertions will ultimately prevail in litigation.

On the same day, we also filed an answer to Optumsoft’s claims, as well as affirmative defenses based in part on Optumsoft’s failure to maintain the confidentiality of its claimed trade secrets, its authorization of the disclosures it asserts and its delay in claiming ownership of the software components at issue. We have also taken additional steps to respond to Optumsoft’s allegations that we improperly used and/or disclosed Optumsoft confidential information. While we believe we have strong defenses to these allegations, we believe we have (i) revised our software to remove the elements we understand to be at issue and made the revised software available to our customers and (ii) removed information from our website that Optumsoft asserted disclosed Optumsoft confidential information.

We intend to vigorously defend against Optumsoft’s lawsuit. However, we cannot be certain that, if litigated, any claims by Optumsoft would be resolved in our favor. For example, if it were determined that Optumsoft owned components of our EOS network operating system, we would be required to transfer ownership of those components and any related intellectual property to Optumsoft. If Optumsoft were the owner of those components, it could make them available to our competitors, such as through a sale or license. In addition, Optumsoft could assert additional or different claims against us, including claims that our license from Optumsoft is invalid. Additionally, the existence of this lawsuit could cause concern among our customers and potential customers and could adversely affect our business and results of operations. An adverse litigation ruling could also result in a significant damages award against us and the injunctive relief described above. In addition, if our license was ruled to have been terminated, and we were not able to negotiate a new license from Optumsoft on reasonable terms, we could be required to pay substantial royalties to Optumsoft or be prohibited from selling products that incorporate Optumsoft intellectual property. Any such adverse ruling could materially adversely affect our business, prospects, results of operation and financial condition. Whether or not we prevail in the lawsuit, we expect that the litigation will be expensive, time-consuming and a distraction to management in operating our business.

We do not believe a loss is probable; however, it is reasonably possible. Due to the early stage of this matter, no estimate of the amount or range of possible amounts can be determined at this time.