Créateurs, a local newsletter asked me to write short articles about famous success stories. I decided to begin with Adobe and its founders John Warnock and Charles Geschke. You will find the full text below as well as the usual data I like to give about start-ups: the capitalisation table of the company at its IPO and how shareholding evolved from foundation to public offering. Here is the article you may found in french in the Newsletter.

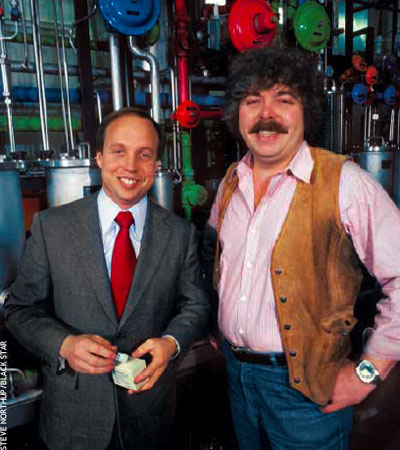

John Warnock and Charles Geschke: Adobe

Start-ups are very often associated to their founders. Entrepreneurs such as Steve Jobs or Bill Gates are obviously linked to the company they created. John Warnock and Charles Geschke may be less famous but their story is as fascinating.

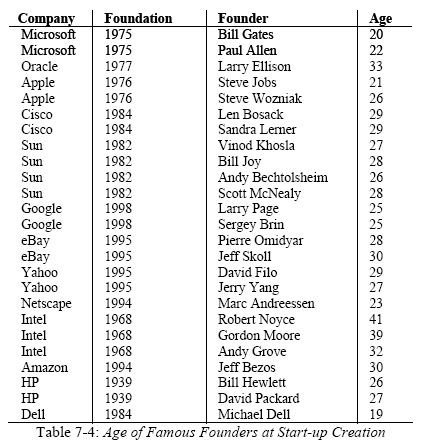

Without the profile of the atypical entrepreneur (they are not “school dropouts” who launched their venture in their twenties), Warnock and Geschke founded Adobe Systems in 1982 when they were more than 40-year-old. Adobe is famous for some of the most popular software worldwide such as Acrobat and Photoshop.

From the printer to the printing protocol

It all began in the 70’s, at the renowned Palo Alto Research Park of Xerox, the vendor of copy machines. The two engineers are more and more frustrated. Xerox may have enabled the development of the computer mouse, word processing, email or Ethernet, but it has been incapable of transforming them in commercial products. Warnock and Geschke cannot convince their management of the potential of their research. “Part of it was fear and misunderstanding” but they also admit that “in fairness to the management, I think we as researchers were a little naïve about what it would take to get these things from conceptual operating prototypes all the way to full-production, supportable products. But we sort of hoped that they would hire the people who could do that.”

They left Xerox in 1982 and raised $2.5M to develop their project: high quality printers and a system which connect them to computer networks. When they met potential customers (Apple, Dec), they discovered that nobody is really interested. Steve Jobs explains to them that he needs their printer protocol, Postscript, for the Macintosh he is developing. They immediately change their business plan. Adobe became a software company with the success we all know.

Some good advice

Their vision of what is an entrepreneur is enlightening. It was more an accident than a destiny. But today their advice is worth reading.

You should always be flexible. You should try and explore many solutions, test them with customers and abandon the wrong ones very fast. They have the same views on the personality of entrepreneurs: “99% of founders fail because they cannot change and want to control too much”.

Passion, risk taking and self-confidence seem to be the critical strengths of entrepreneurs combined with intelligence and hard work. “But this is not sufficient. Luck also plays a major role.

When their age and experience is mentioned, Geschke adds that “I don’t think there’s any mystery in running a business. I think it helped that we were in our 40s, that we had worked for a variety of organizations. We had worked in other companies, but tried to leave their bad ideas as proprietary to them. We tried to pick the best things that we saw.” What is essential is to have a vision of what you want to do. “I am not a hunter, never have fired a gun, but I’m told that if you want to shoot a duck, you have to shoot where the duck is going to be, not where the duck is. It’s the same with introducing technology: if you’re only focused on the

market today, by the time you introduce your solution to that problem, there’ll probably be several others already entrenched.”

The ingredients of success

From the initial frustration which is at the origin of their departure from Xerox to the success of Adobe, the lessons are many. Never be a one-product company; technology cannot be simply transferred, you need to add brain power, hire good professionals; and as founders, you need to have “the intellectual capability, inherent honesty, ethical behavior and principles by which we lead [your] personal and business lives.”

In a few sentences, the ingredients of success are numerous, complex as well as simple and probably common to all great entrepreneurs.

To know more about Adobe:

The Revolutionaries: www.thetech.org/exhibits/online/revolution

Adobe Systems, Computer History Museum: www.computerhistory.org

Founders at Work, J. Livingston, Apress (2007)

In the company of Giants, R. Jager and R. Ortiz, Mcgraw-Hill (1997)

Next Article: Bob Swanson: Genentech

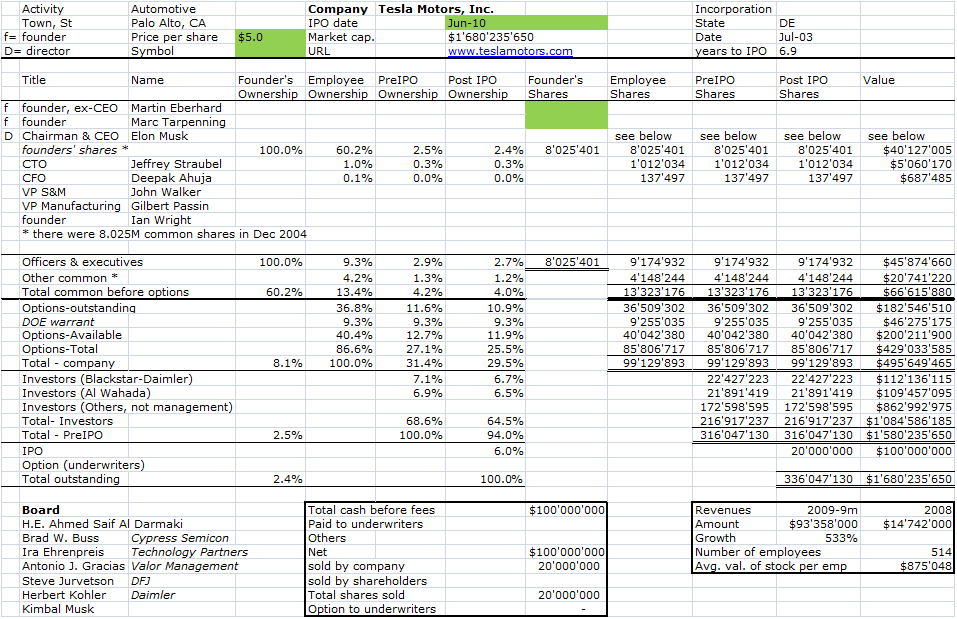

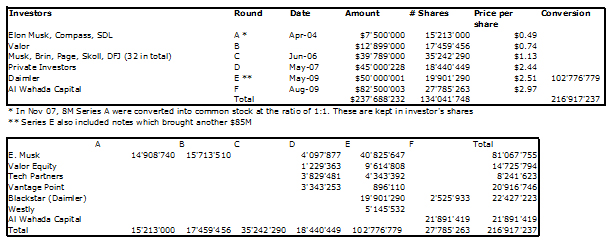

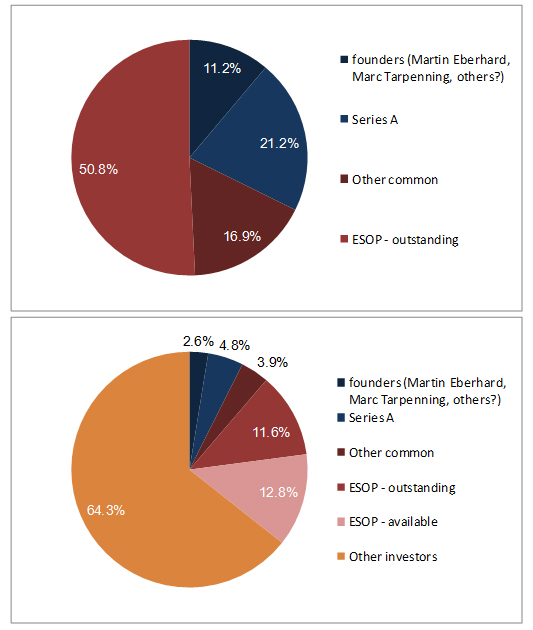

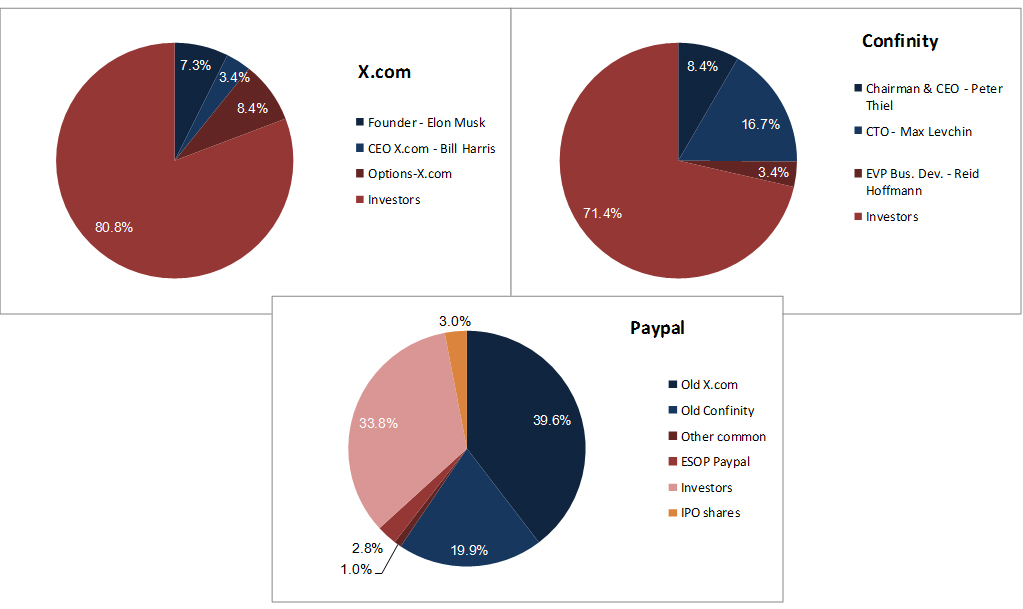

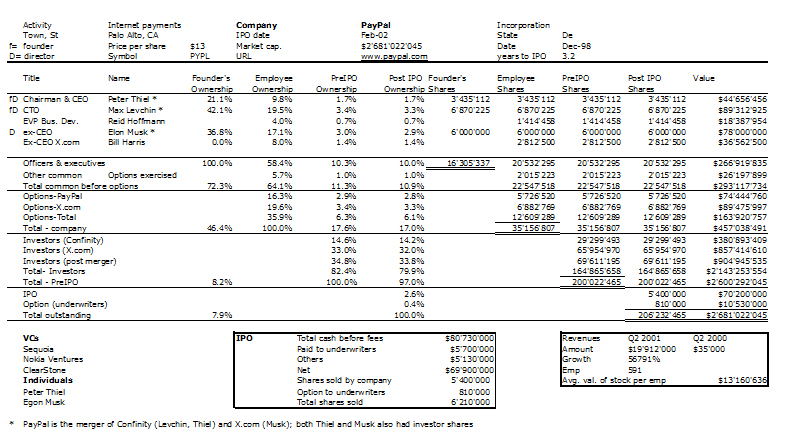

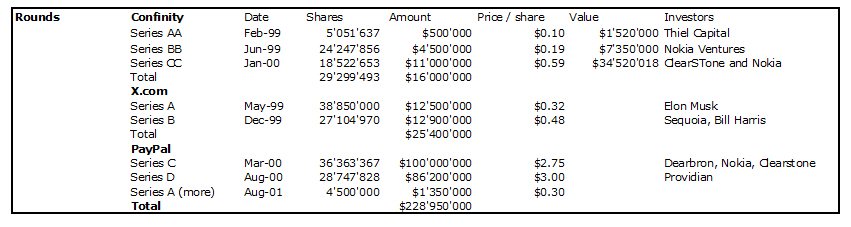

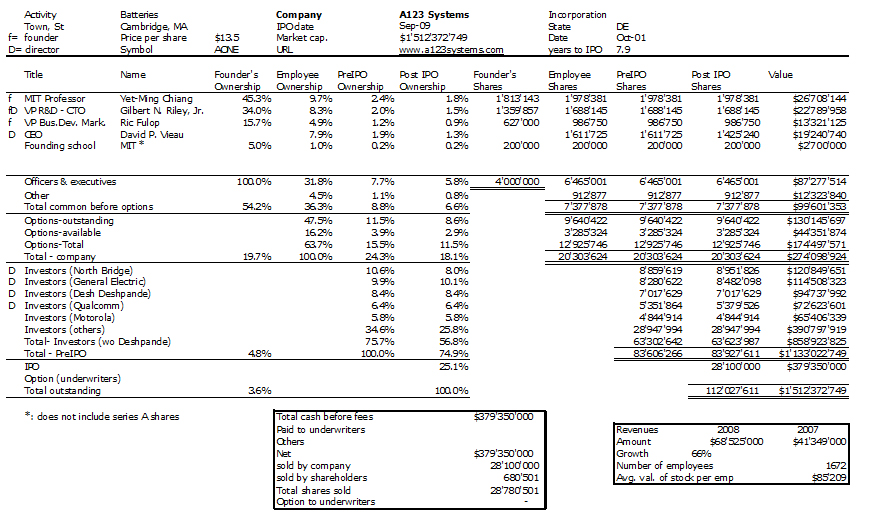

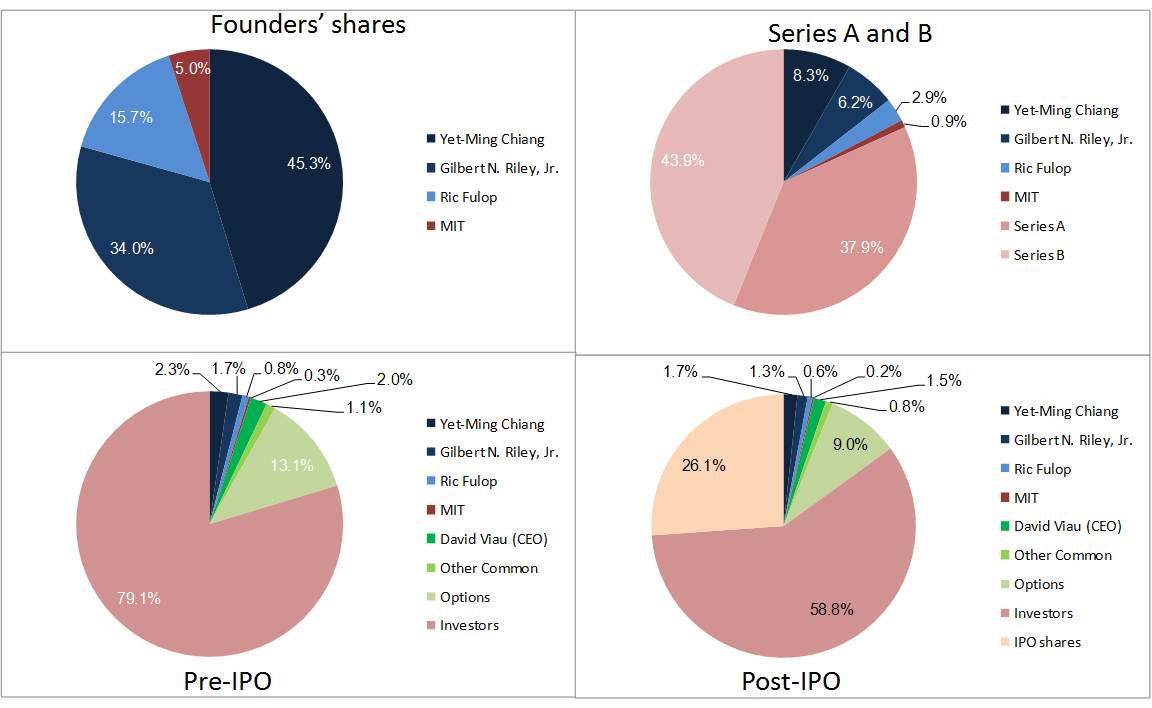

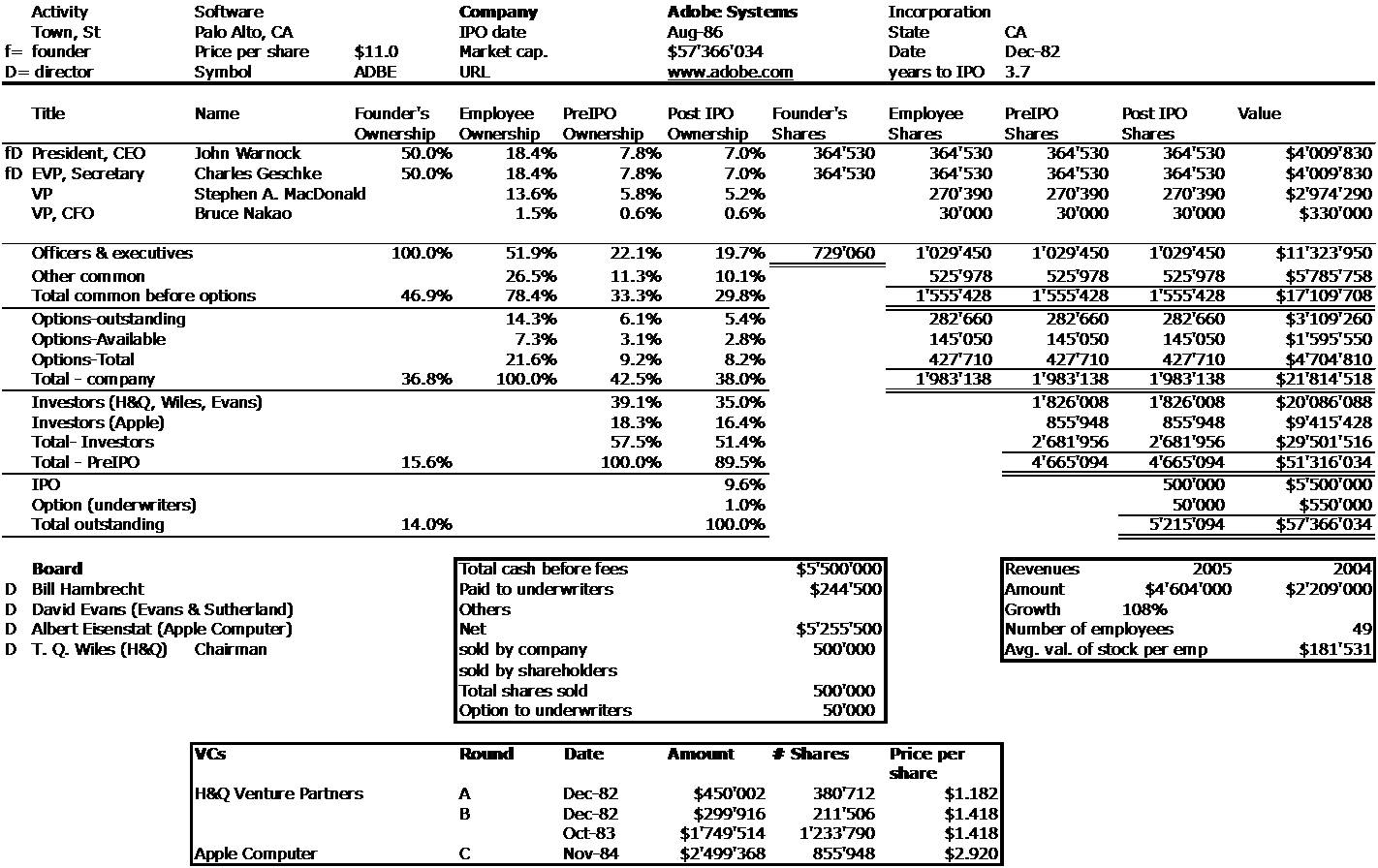

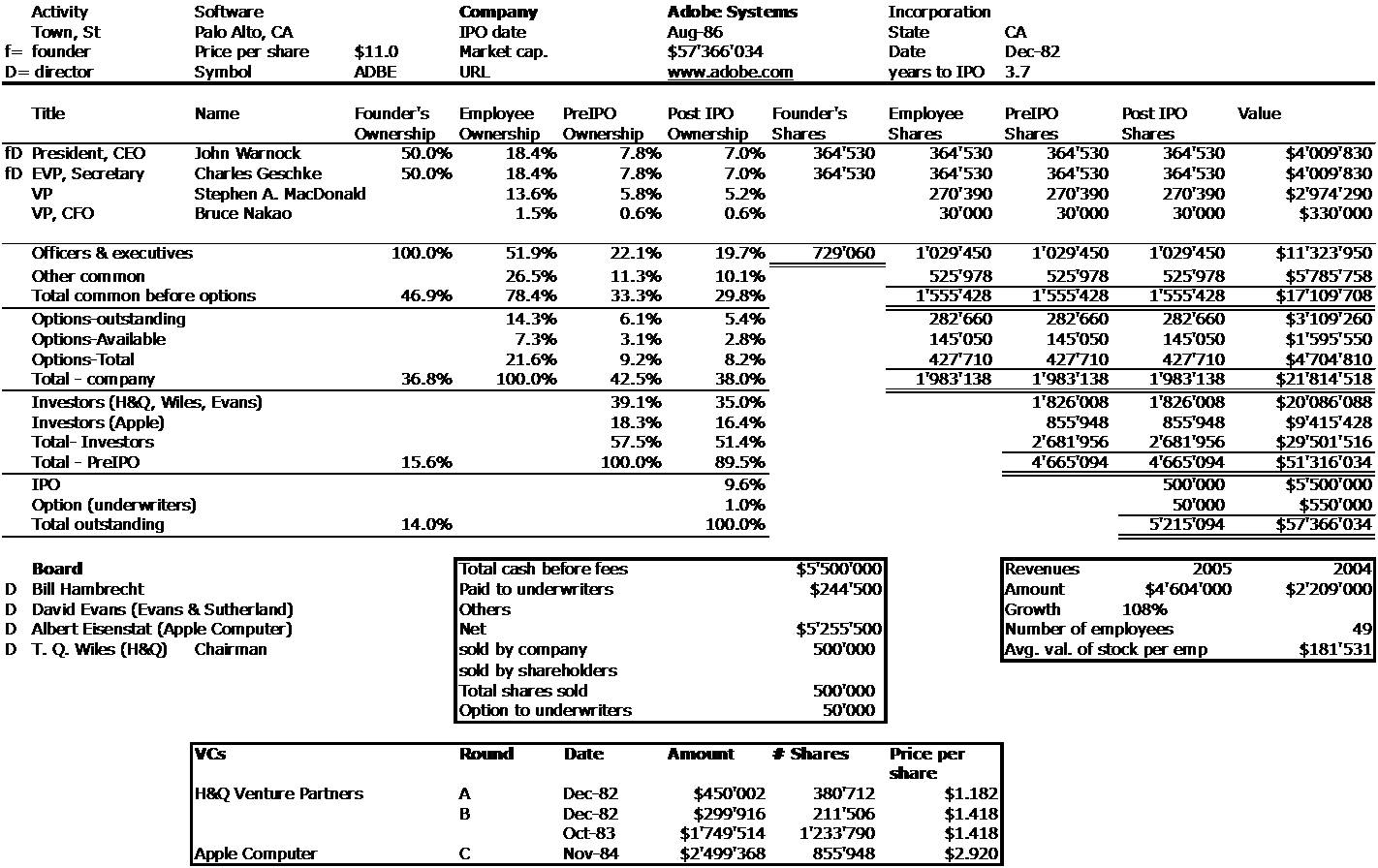

Now the cap. table in 1986

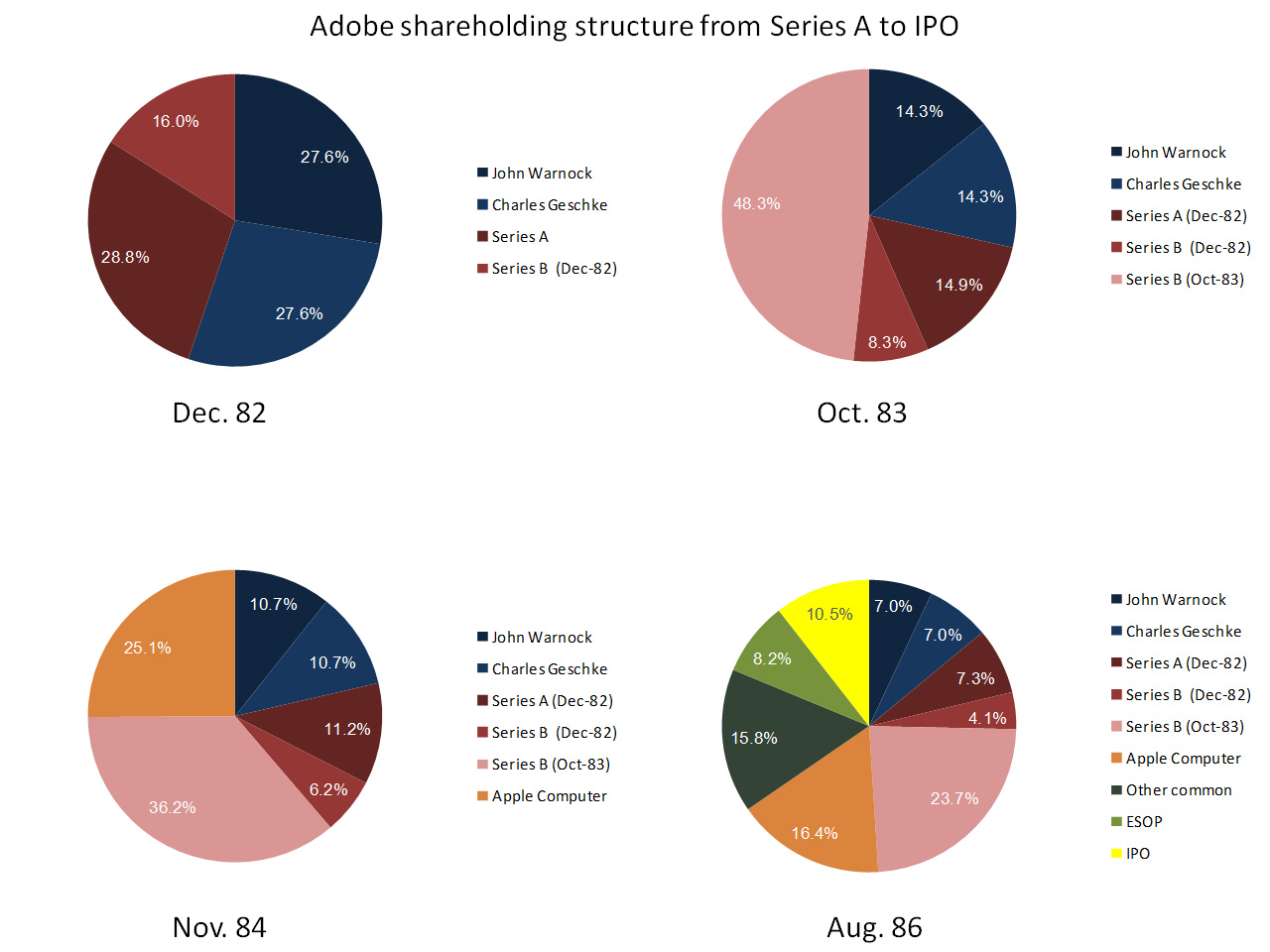

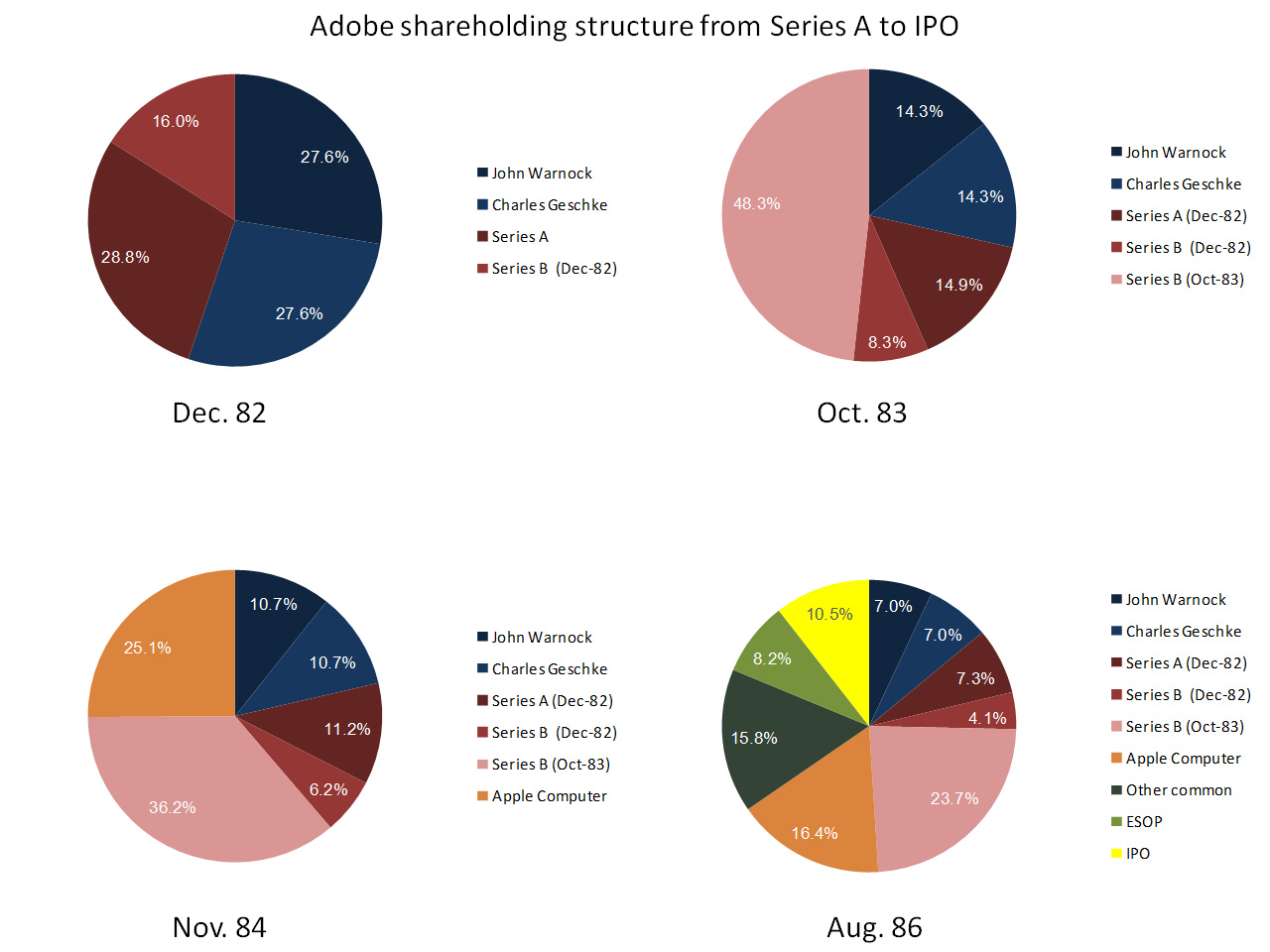

and the shareholding structure from 1982 to 1986: