I began this blog in July 2007, so more than 15 years ago. I began my professional activity around startups in September 1997, so more than 25 years ago. So many adventures, so many great moments. And so much book reading! I revisited these pages and did an exhaustive list of the books I could remember reading. Most have a post somewhere in the blog.

I created a little artificially 6 categories:

– About Google and Apple

– Entrepreneurs’ Biographies

– Startup Stories and Analyses

– Ecosystems and Innovation

– Venture Capital

– How to

– Fictions / Thrillers (or close)

Here they are… Enjoy (maybe!)

About Google and Apple

- Goomics, Google’s corporate culture revealed through internal comics, Manu Cornet

- In the Plex, How Google Thinks, Works and Shapes Our Lives, Stephen Levy

- How Google Works, Eric Schmidt, Jonathan Rosenberg

- Dogfight, How Apple and Google Went to War and Started a Revolution, Fred Vogelstein

- I’M Feeling Lucky, Falling On My Feet in Silicon Valley, Douglas Edwards

- The Apple Revolution, Steve Jobs, the Counter Culture and How the Crazy Ones Took Over the World, Luke Dormehl

- Work Rules! Insights from inside Google that will transform how you live and lead, Laszlo Bock

- The Google Story, David Vise

- Return to the Little Kingdom, How Apple and Steve Jobs Changed the World, Michael Moritz

Biographies

- Elon Musk, Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for A Fantastic Future, Ashlee Vance

- Steve Jobs, La vie d’un génie, Walter Isaacson

- Inside Steve’s Brain, Leander Kahney

- The Man Behind the Microchip, Robert Noyce and the Invention of Silicon Valley, Leslie Berlin

Startups Stories / Analyses

- Trillion Dollar Coach, The Leadership Playbook of Silicon Valley’s Bill Campbell, Eric Schmidt, Jonathan Rosenberg, and Alan Eagle

- L’entrepreneuriat en action, Ou comment de jeunes ingénieurs créent des entreprises innovantes, Philippe Mustar

- Chercheurs et entrepreneurs : c’est possible ! Belles histoires du numérique à la française, Laurent Kott, Antoine Petit

- Bad Blood, Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup, John Carreyrou

- Bienvenue dans le Nouveau Monde, Comment j’ai survécu à la coolitude des startups, Mathilde Ramadier

- Les start-up expliquées à ma fille, L’entrepreneuriat vu de l’intérieur, Guillene Ribière

- Startup, Arrêtons la mascarade, Contribuer vraiment à l’économie de demain, Nicolas Menet, Benjamin Zimmer

- No Exit, Struggling to Survive a Modern Gold Rush, Gideon Lewis-Kraus

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things, Building a Business When There are no Easy Answers, Ben Horowitz

- Zero to One, Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future, Peter Thiel, Blake Masters

- Startupland, How Three Guys Risked Everything to Turn an Idea into a Global Business, Mikkel Svane, Carlye Adler

- European Founders at Work, Pedro Gairifo Santos

- Founders at Work, Stories of Startups’ Early Days, Jessica Livingston

- The Monk and the Riddle, The Education of a Silicon Valley Entrepreneur, Randy Komisar

- Once you’re lucky, Twice you’re good, The Rebirth of Silicon Valley and the Rise of Web, Sarah Lacy

- They Made It! Angelika Blendstrup

- Betting It All, The Entrepreneurs of Technology, Michael Malone,

- In the Company of Giants, Candid Conversations With the Visionaries of the Digital World, Rama Dev Jager, Rafael Ortiz

- Startup, A Silicon Valley Adventure, Jerry Kaplan

Ecosystems and Innovation

- From the Basement to the Dome, How MIT’s Unique Culture Created a Thriving Entrepreneurial Community, Jean-Jacques Degroof

- The Microchip Revolution: A brief history, Luc O. Bauer, E. Marshall Wilder

- The Code, Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America, Margaret O’Mara

- Loonshots or how to nurture crazy ideas, Safi Bahcall

- Troublemakers, How Generation of Silicon Valley Upstarts Invented the Future, Leslie Berlin

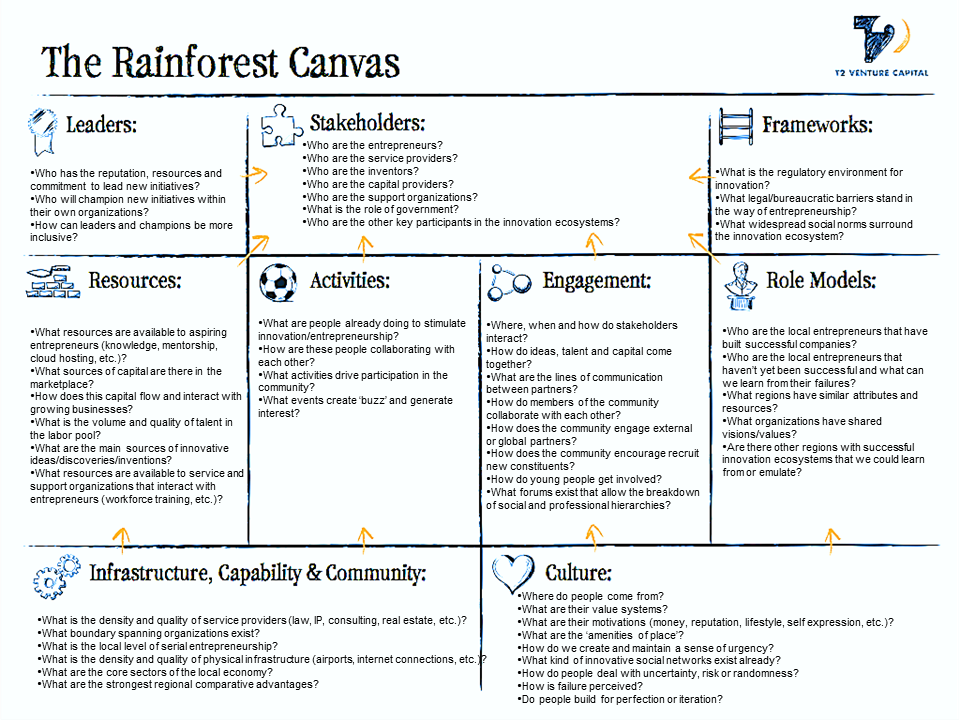

- The Rainforest, The Secret to Building the Next Silicon Valley, Victor W. Hwang, Greg Horowitt

- The Innovators, How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution, Walter Isaacson

- The Entrepreneurial State, Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths, Mariana Mazzucato

- Genentech, The Beginnings of Biotech, Sally Smith Hughes

- Science Lessons, What the Business of Biotech Taught Me About Management, Gordon Binder

- Le prochain Google sera Suisse (à 10 conditions), Fathi Derder

- Prophet of Innovation, Joseph Schumpeter and Creative Destruction, Thomas McCraw

- Start-up Nation, The Story of Israel’s Economic Miracle, Dan Senor, Saul Singer

- Boulevard of Broken Dreams, Why Public Efforts to Boost Entrepreneurship and Venture Capital Have Failed–and What to Do About It, Josh Lerner

- The Innovation Illusion, How So Little is Created by So Many Working So Hard, Fredrik Erixon, Bjorn Weige

- Un paléoanthropologue dans l’entreprise, S’adapter et innover pour survivre, Pascal Picq

- Against Intellectual Monopoly, Michele Boldrin and David K. Levine

- The New Argonauts, Regional Advantage in a Global Economy, AnnaLee Saxenian

- Regional Advantage, Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128, AnnaLee Saxenian

- Silicon Valley Fever, Growth of High Technology Culture, Everett M. Rogers, Judith K. Larsen

- Creating the Cold War University, The Transformation of Stanford, Rebecca S. Lowen

- Nurturing Science-based Ventures, An International Case Perspective, Ralf Seifert, Benoït Leleux, Christopher Tucci

- Entrepreneurship and Innovation, Peter F. Drucker

- The Gorilla Game, Picking Winners in High Technology, Geoffrey Moore

- Inside the Tornado, Strategies for Developing, Leveraging, and Surviving Hypergrowth Markets, Geoffrey Moore

- Crossing the Chasm, Marketing and Selling High-Tech Products to Mainstream Customers, Geoffrey Moore

- The Founder’s Dilemmas, Anticipating and Avoiding the Pitfalls That Can Sink a Startup, Noam Wasserman

- The Innovators Dilemma, When New Technologies Cause Good Firms To Fail, Clayton M. Christensen

- Accidental Empires, How the Boys of Silicon Valley Make Their Millions, Battle Foreign Competition, and Still Can’t Get a Date, Robert X. Cringley

Venture Capital

- The Power Law, Venture Capital and the Making of the New Future, Sebastian Mallaby

- The Masters of Private Equity and Venture Capital, Management Lessons from the Pioneers of Private Investing, Robert A. Finkel

- The Startup Game, Inside the Partnership between Venture Capitalists and Entrepreneurs, William H. Draper III

- Creative Capital, Georges Doriot and the Birth of Venture Capital, Spencer Ante

- The Business of Venture Capital, Insights from Leading Practitioners on the Art of Raising a Fund, Deal Structuring, Value Creation, and Exit Strategies, Mahendra Ramsinghani

- The New Venturers, Inside the High-Stakes World of Venture Capital, John Wilson

How To

- The Mom Test, How to talk to customers & learn if your business is a good idea when everyone is lying to you, Rob Fitzpatrick

- Straight Talk for Startups, 100 Insider Rules for Beating the Odds, Randy Komisar, Jantoon Reigersman

- Measure What Matters, OKRs, The Simple Idea that Drives 10x Growth, John Doerr,

- The start-up of You, Adapt to the Future, Invest in Yourself, and Transform Your Career, Reid Hoffman

- Don’t f**k it up, How Founders and Their Successors Can Avoid the Clichés That Inhibit Growth, Les Trachtman

- How To Start a Business That Doesn’t Suck (and will actually turn a profit), Michael Clarke

- The Four Steps to the Epiphany, Successful Strategies for Products That Win, Steve Blank (NB: the book has been updated and renamed as The Startup Owner’s Manual, The Step-by-Step Guide for Building a Great Company, Steve Blank, Bob Dorf)

- The Lean Startup, How Today’s Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses, Eric Ries

- Business Model Generation, Alexander Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur

- Slicing Pie, Funding Your Company Without Funds, Mike Moyer

- Getting to Plan B, Breaking Through to a Better Business Model, John Mullins, Randy Komisar

- Winning Opportunities, Proven Tools for Converting Your Projects into Success (without a Business Plan), Raphael Cohen

- Start-up, (anti-)bible à l’usage des fous et des futurs entrepreneurs, Bruno Martinaud

- The Art of the Start, GuyKawasaki

Fiction / Thrillers or close