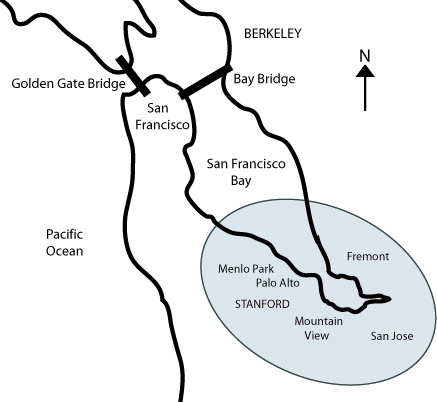

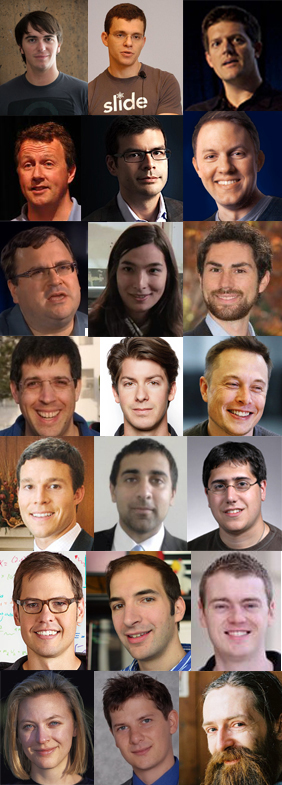

Part 3 of my series of comments about Thiel’s class notes at Stanford mainly cover his Class 5-8. But first I should add that Thiel invited a “honor class” of innovators during his 19 classes. Quite fascinating!

1st row: Stephen Cohen, co-founder and Executive VP of Palantir Technologies,

1st row: Stephen Cohen, co-founder and Executive VP of Palantir Technologies,

Max Levchin, co-founder PayPal and Slide,

Roelof Botha, partner at Sequoia Capital and former CFO of PayPal,

2nd row: Paul Graham, partner and co-founder of Y Combinator,

Bruce Gibney, partner at Founders Fund,

Marc Andreessen, general partner Andreessen Horowitz,

3rd row: Reid Hoffman, co-founder of LinkedIn,

Danielle Fong, Co-founder and Chief Scientist of LightSail Energy,

Jon Hollander, Business Development at RoboteX,

4th row: Greg Smirin, COO of The Climate Corporation,

Scott Nolan, Principal at Founders Fund and former aerospace engineer at SpaceX,

(Elon Musk was going to come, but he was busy launching rockets),

5th row: Brian Slingerland. Co-Founder, President & COO at Stem CentRx,

Balaji S. Srinivasan, CTO of Counsyl,

Brian Frezza, Co-founder, Emerald Therapeutics,

6th row: D. Scott Brown, co-founder of Vicarious,

Eric Jonas, CEO of Prior Knowledge,

Bob McGrew, Director of Eng, Palantir,

7th row: Sonia Arrison, Associate Founder of Singularity University,

Michael Vassar, the Singularity Institute for the study of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI),

Aubrey de Grey, Chief Science Officer at the SENS Foundation.

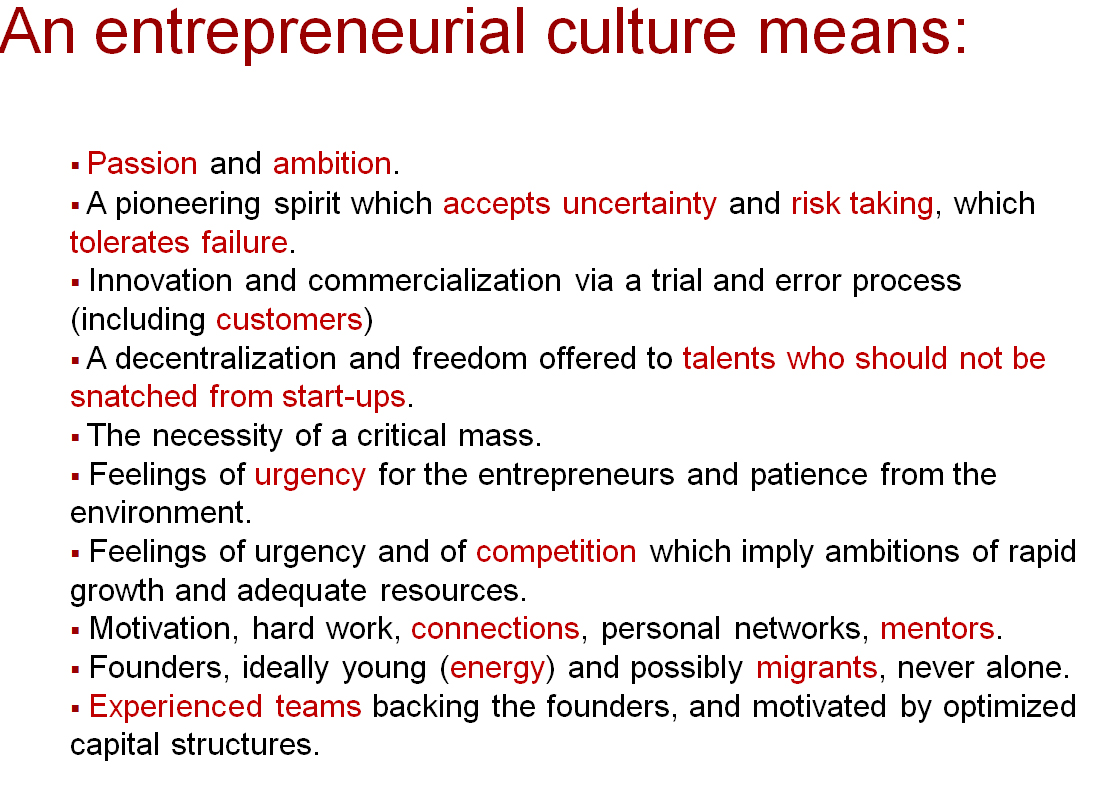

Thiel covered how to build a company from the ideas and vision of founders, through hiring and sometimes funding from investors. But he began with a critical though fuzzy concept, the company culture: “A robust company culture is one in which people have something in common that distinguishes them quite sharply from rest of the world.”

He mentions also some important dimensions of the culture:

– Consultant-nihilism or Cultish Dogmatism: “You want to be somewhere in the middle of that spectrum. To the extent you gravitate towards an extreme, you probably want to be closer to being a cult than being an army of consultants.” which could be why Thiel said earlier,

pre-money valuation = ($1M*n_engineers) – ($500k*n_MBAs).

– To Fight or Not To Fight (i.e. Nerds or Athletes or again Zero-sum and Non zero-sum). “So you have to strike the right balance between nerds and athletes. Neither extreme is optimal. Consider a 2 x 2 matrix. On the y-axis you have zero-sum people and non zero-sum people. On the x-axis you have warring, competitive environments and then you have peaceful, monopoly/capitalist environments. The optimal spot on the matrix is monopoly capitalism with some tailored combination of zero-sum and non zero-sum oriented people. You want to pick an environment where you don’t have to fight. But you should bring along some good fighters to protect your non zero-sum people and mission, just in case.”

I was just told this is crytic… I agree… another reason to read Thiel directly!

“Foundings are obviously temporal. But how long they last can be a hard question. The typical narrative contemplates a founding, first hires, and a first capital raise. But there’s an argument that the founding lasts a lot longer than that. The idea of going from 0 to 1—the idea of technology—parallels founding moments. The 1 to n of globalization, by contrast, parallels post-founding execution. It may be that the founding lasts so long as a company’s technical innovation continues. Founders should arguably stay in charge as long as the paradigm remains 0 to 1. Once the paradigm shifts to 1 to n, the founding is over. At that point, executives should execute.”

Max Levchin: The notion that diversity in an early team is important or good is completely wrong. You should try to make the early team as non-diverse as possible. There are a few reasons for this. The most salient is that, as a startup, you’re underfunded and undermanned. It’s a big disadvantage; not only are you probably getting into trouble, but you don’t even know what trouble that may be. Speed is your only weapon. All you have is speed. […] How to hire? A specific application of this is the anti-fashion bias. You shouldn’t judge people by the stylishness of their clothing; quality people often do not have quality clothing. Which leads to a general observation: Great engineers don’t wear designer jeans. So if you’re interviewing an engineer, look at his jeans. There are always exceptions, of course. But it’s a surprisingly good heuristic. […] PayPal also had a hard time hiring women. An outsider might think that the PayPal guys bought into the stereotype that women don’t do CS. But that’s not true at all. The truth is that PayPal had trouble hiring women because PayPal was just a bunch of nerds! They never talked to women. So how were they supposed to interact with and hire them?

“No CEO should be paid more than $150k per year” (in Silicon Valley)

“Another important insight is that people must either be fully in the company or not in it at all.”

Dilution and funding

Building a valuable company is a long journey. A key question to keep your eye on as a founder is dilution. The Google founders had 15.6% of the company at IPO. Steve Jobs had 13.5% of Apple when it went public in the early ‘80s. Mark Pincus had 16% of Zynga at IPO. If you have north of 10% after many rounds of financing, that’s generally a very good outcome. Dilution is relentless. The alternative is that you don’t let anyone else in. It’s worth remembering that many successful businesses are built like this. Craigslist would be worth something like $5bn if it were run more like a company than a commune. GoDaddy never took funding. Trilogy in the late 1990s had no outside investors. Microsoft very nearly joined this club; it took one small venture investment just before its IPO. When Microsoft went public, Bill Gates still owned an astounding 49.2% of the company. So the question to think about with VCs isn’t all that different than questions about co-founders and employees. Who are the best people? Who do you want—or need—on board?

The VC model in a nutshell: a power law. “To a first approximation, a VC portfolio will only make money if your best company investment ends up being worth more than your whole fund. (And the investment in the second best company is about as valuable as number three through the rest.)”

I have not yet read the following classes…