Not many people ever heard of Georges Doriot. I knew his name because I know a little about VC (you can always check my visual history of VC). But I did not know much about him. Now that I read Creative Capital by Spencer Ante, I know much more. As usual, when I comment books, I mostly do some copy-pastes. Here they are:

In 1921, Doriot came to America on a steamship. Even though he had no friends or family in the United States, never graduated from college, and dropped out of graduate school, the Frenchman became, arguably, the most influential and popular professor at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Business. Over three generations, Doriot taught thousands of students [Page xiv].

He was early to recognize the importance of globalization and creativity in the business world. “A lot of the things that were attributed to Peter Drucker [link blog] were Doriot’s ideas” says Charles P. Waite [Page xv].

He believed in building companies for the long haul, not flipping them for a quick profit. Returns were the by-product of hard labor, not a goal. Doriot often worked with a company for a decade or more before realizing any return. That is why he often referred to his companies as his “children”. “When you have a child, you don’t ask what return you can expect” Doriot was quoted in a 1967 Fortune story “Of course, you have hopes – you hope the child will become President of the United States. But that is not very probable. I want them to do outstandingly well in their field. And if they do, the rewards will come. But if a man is good and loyal and does not achieve a so-called good rate of return, I will stay with him. Some people don’t become geniuses until after they are 24, you know. If I were a speculator, the question, of return would apply. But I don’t consider a speculator – in my definition of the word – constructive. I am building men and companies.” [Page xvii]

“A creative man merely has ideas; a resourceful man makes them practical.” [Page xviii]

[He] ushered a new era of corporate culture. At Digital, the engineer was king. Hierarchy was out. Controlled chaos was in. Like Jack Kerouac and the Beat Generation, Digital was a petri dish in which the counterculture was spawned in the late 1950s. “He was definitely part of a social revolution that loosened things up.”

For 20 years Doriot was a professor and a business advisor. “How did a man with hardly any experience running a business come to be such a world-class businessman? The answer is that during those years, dozens of companies hired the professor to help guide them through the worst disaster that ever hit the American economy. In that dark decade, Doriot gained a lifetime experience as an officer, director and consultant” [page 64].

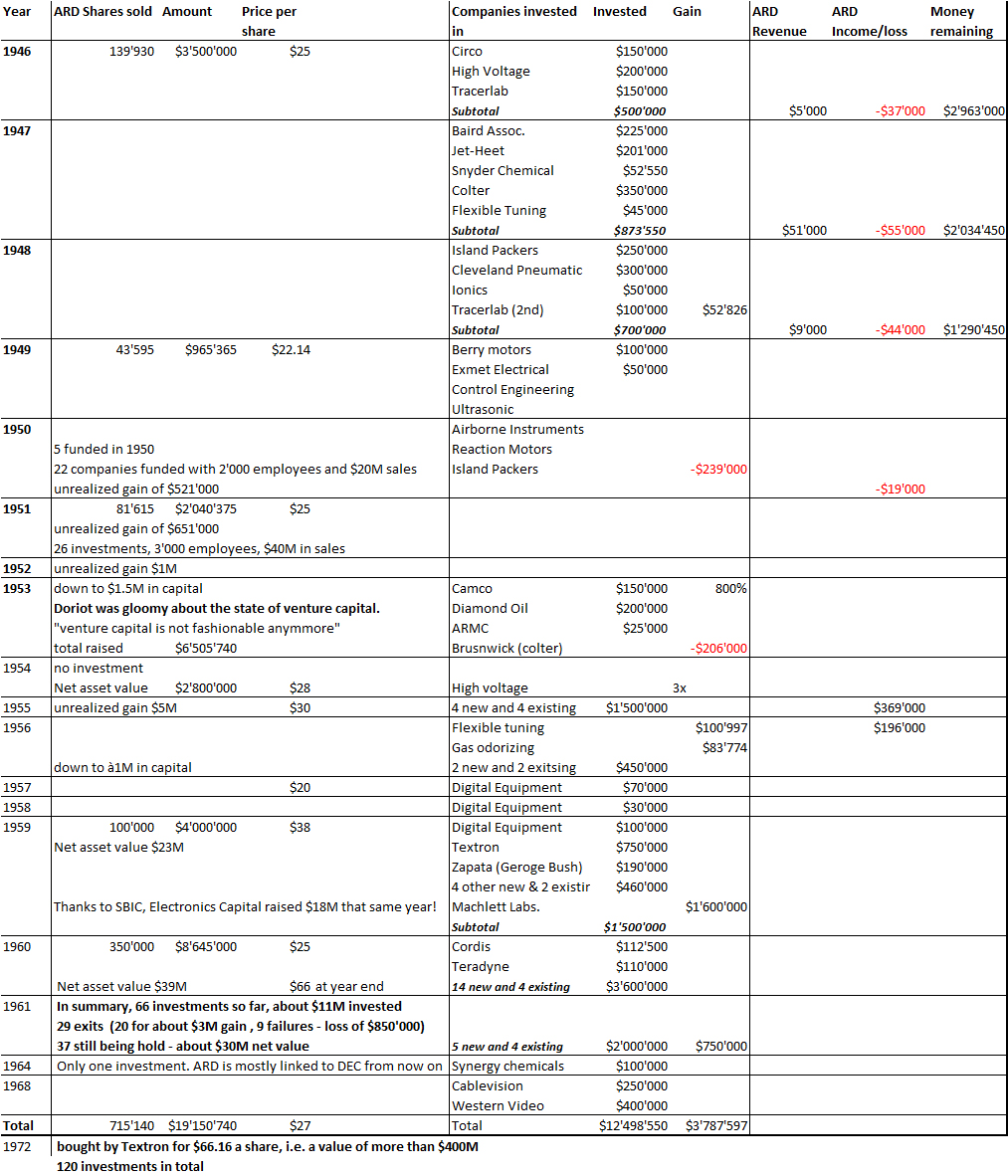

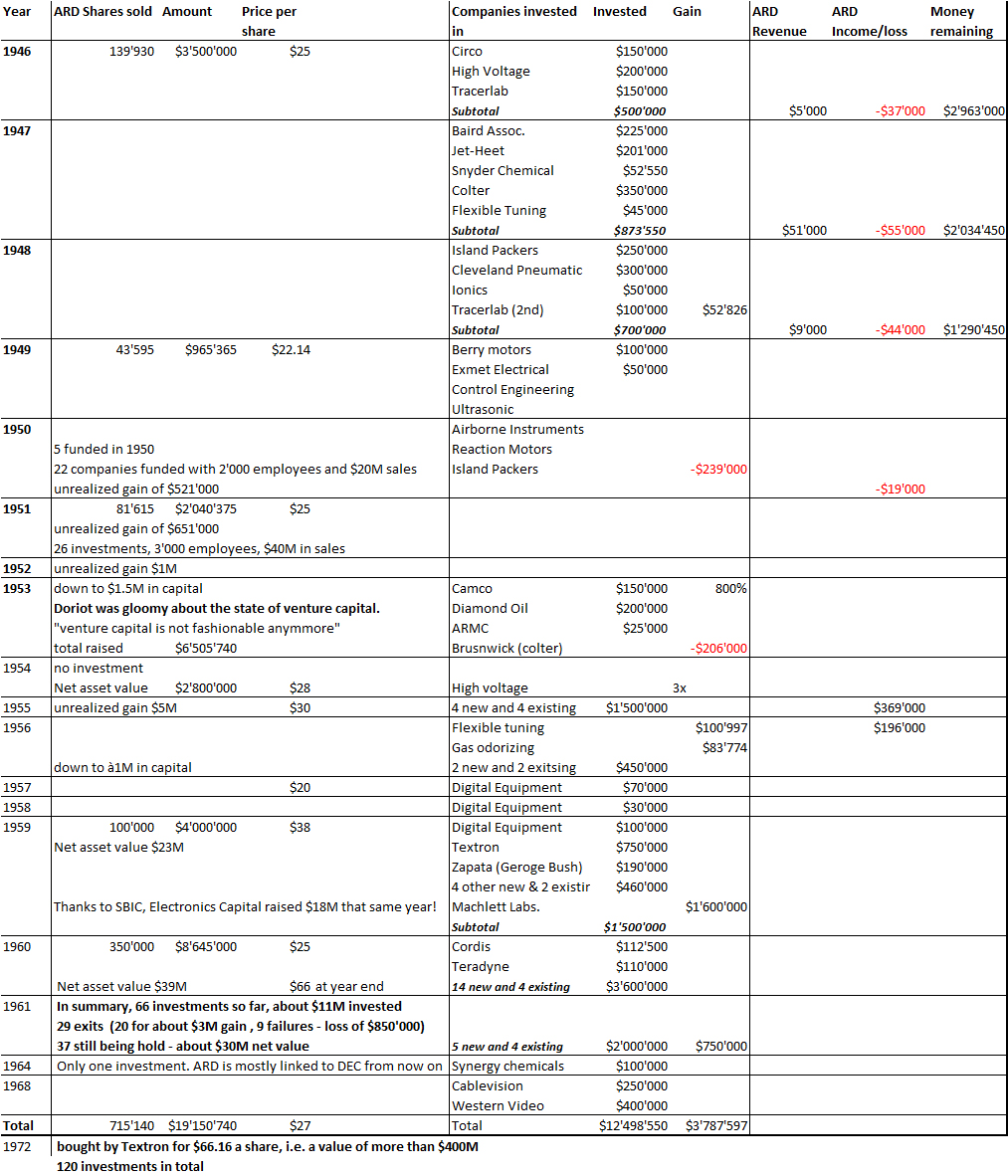

American Research and Development Corporation (ARD)

The idea of an entity helping companies by making risky investments was born before World War II but could be implemented only in 1946. On June 6, 1946, the American Research and Development Corporation (ARD) was incorporated under Massachusetts law. It believed in “innovation, risk-taking and an unwavering belief in human potential”. They also realized that organizations with fiduciary resources and the seasoned operators running them were not daredevils skilled in the art of invention and that, conversely, inventors were struggling creative types with no money. ARD sought to bring together these two independent yet largely separate communities.

Typically, ARD preferred to take a hands-off approach. They were there to coach, guide and inspire. Running the business was the job of the entrepreneur. But quite often, circumstances called for more drastic action. [Page 121]

“Never go in venture capital if you want a peaceful life”. [Page 126] In 1953, Doriot was gloomy about the state of venture capital. “Venture capital is not fashionable anymore.” Waves of technologies seemed to come out of nowhere and crash onshore every twenty or thirty years. The trick of a venture capitalist was to catch the wave several years before it crested ad to bail out before it crashed. [Looks like speculation, or doesn’t it?] It is interesting to see how the great interest that existed seven or eight years ago in venture capital has disappeared and how the daring and courage which were prevalent at that time have now waned” wrote Doriot. [page 138]

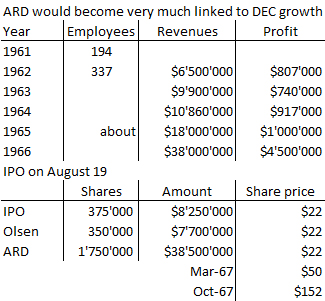

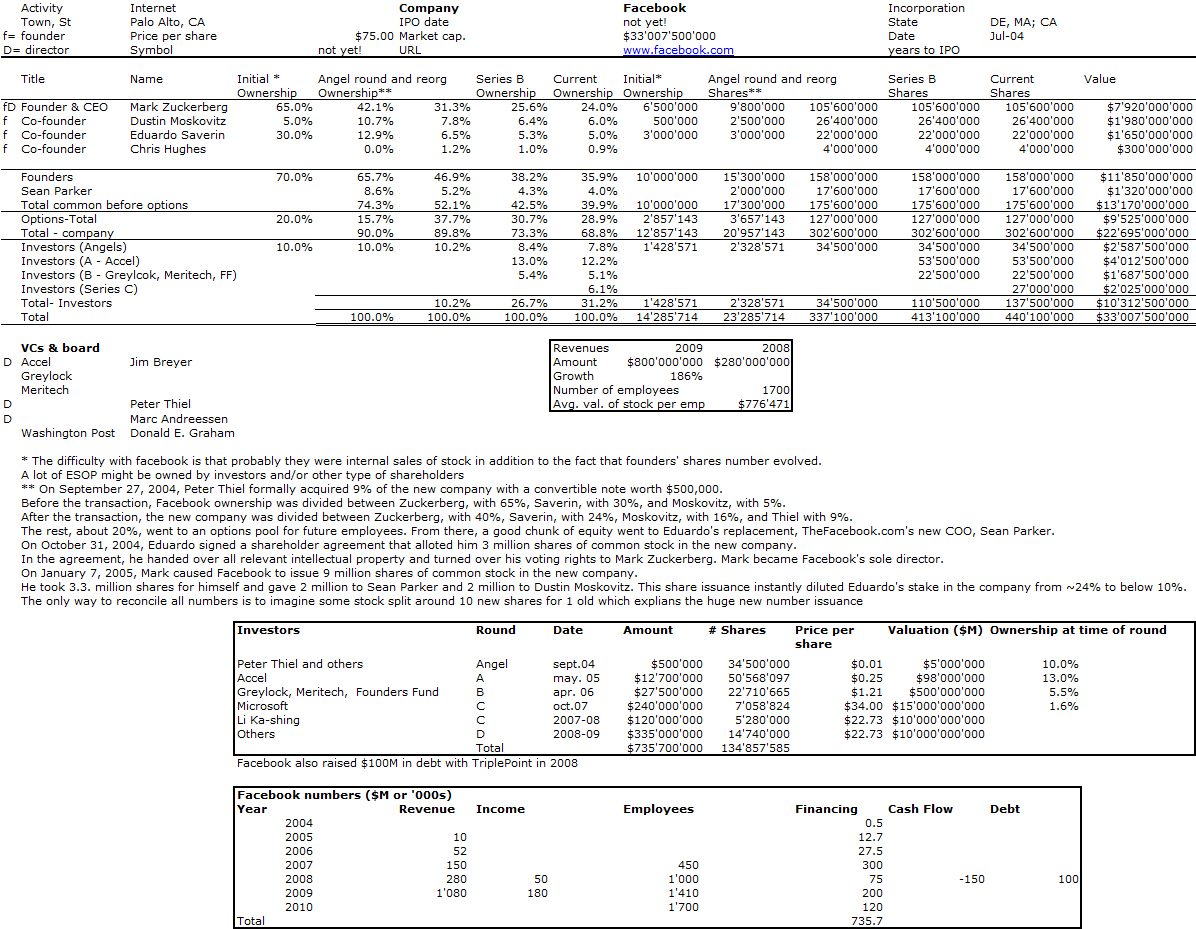

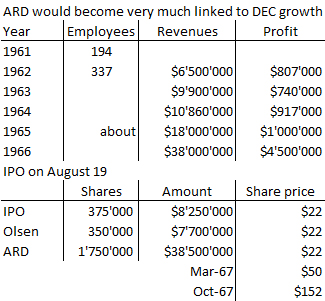

More about ARD’s facts and figures in the table below.

A star is born – 1957

“In the early 1950s, the postwar euphoria of the previous decade that had infused Americans with a sense of infinite possibilities morphed into a Cold War miasma of fear and paranoia. Yet underneath the surface of fear, a subculture of experimentation and rebellion flourished. In the early – to mid-190s, Allen Ginsberg, jack Kerouac, and William Burroughs developed a radical new form of literature that emphasized “stream of consciousness” writing. Modern abstract painting by Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Mark Rothko overthrew European conventions of beauty and form. And in laboratories and universities across the northeastern seaboard, a bunch of scientists and engineers tinkered away on strange but powerful new electronics and computer devices that promised to completely change the way people communicated and conducted business. “ [Page 147]

In the spring 1957 Ken Olsen then at MIT would team up with his buddy Harlan Anderson. They had an idea and a plan. They needed some money. They approached General Dynamics, who “turned them down flat because we didn’t have any business experience.” Then they contacted ARD. ARD had the perfect formula: two grade A men paired with an outstanding idea. ARD offered $70,000 for a 70 percent stake. Ten percent was reserved for a seasoned manager (who would never be found or hired) and the remaining 20% to the 2 founders (12% to Olsen and 8% to Anderson). Because computers were not fashionable, the company project name was changed from Digital Computers to Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC). [Pages 148-150]

The birth of a new industry

1957 was a critical year. America was shocked by the Sputnik. Public money flowed both to R&D with the creation of ARPA (later DARPA) and to venture capital through the new SBIC program. “Many of today’s most successful venture capitalists rightly point out that the SBIC program never created a company of considerable or lasting success. But if the SBIC program did little to advance the art and practice of successful venture investing, it did help propel the venture industry by attracting talented young men who later became pioneers of the field.

In 1957, Doriot also worked at the creation of INSEAD in Paris which was opened in September 1959. Doriot would have 3 careers in his life, a professor at Harvard business school (including helping in the creation of INSEAD), a consultant and even a administrator for the Army, the reason why he was a general and finally a VC with not only ARD but also at the origin of TED (UK), CED (Canada) and EED (Europe).

The success of DEC would make ARD highly successful but would also contribute to its end… As an investment company, ARD was highly regulated; compensation of its employees would become a long battle with SEC and IRS. Only 4 ARD employees would get DEC shares (worth $20M for each individual) and the allocation looked arbitrary to many. “Pressure was growing on ARD to divulge its growing mess of regulatory problems, and to take Digital public. But Doriot did not think Digital was ready to deal with the unforgiving spotlight of public ownership.” [Page 186]

Doriot did not prepare his succession, incentives were low for employees. Some left. Elfers was first and founded Greylock, Waite would follow him. “There was one more reason Elfers left. He realized along with an increasing number of investors in new companies that venture capital and the stock markets mixed as well as oil and water. For Elfers, the solutions to many of ARD’s problems was to take advantage of a new organizational form: the limited partnership (LP). In 1959, the first LP was organized in Palo Alto: Draper, Gaither & Anderson. Then in 1961, Arthur Rock, a former student of Doriot formed Davis & Rock. There were distinct advantages. General partners who ran the firm received not only a management fee, they also received a share of the capital gains. A limited partnership would avoid the glare of public disclosure.” [Page 190]

Still the DEC IPO was a success (see table). “The Digital IPO amounted to a financial revolution. It was really mind-blowing that you could take such a small amount of seed capital and get ownership of a company that was worth more than IBM in a fairly short period of time.” [page 197]

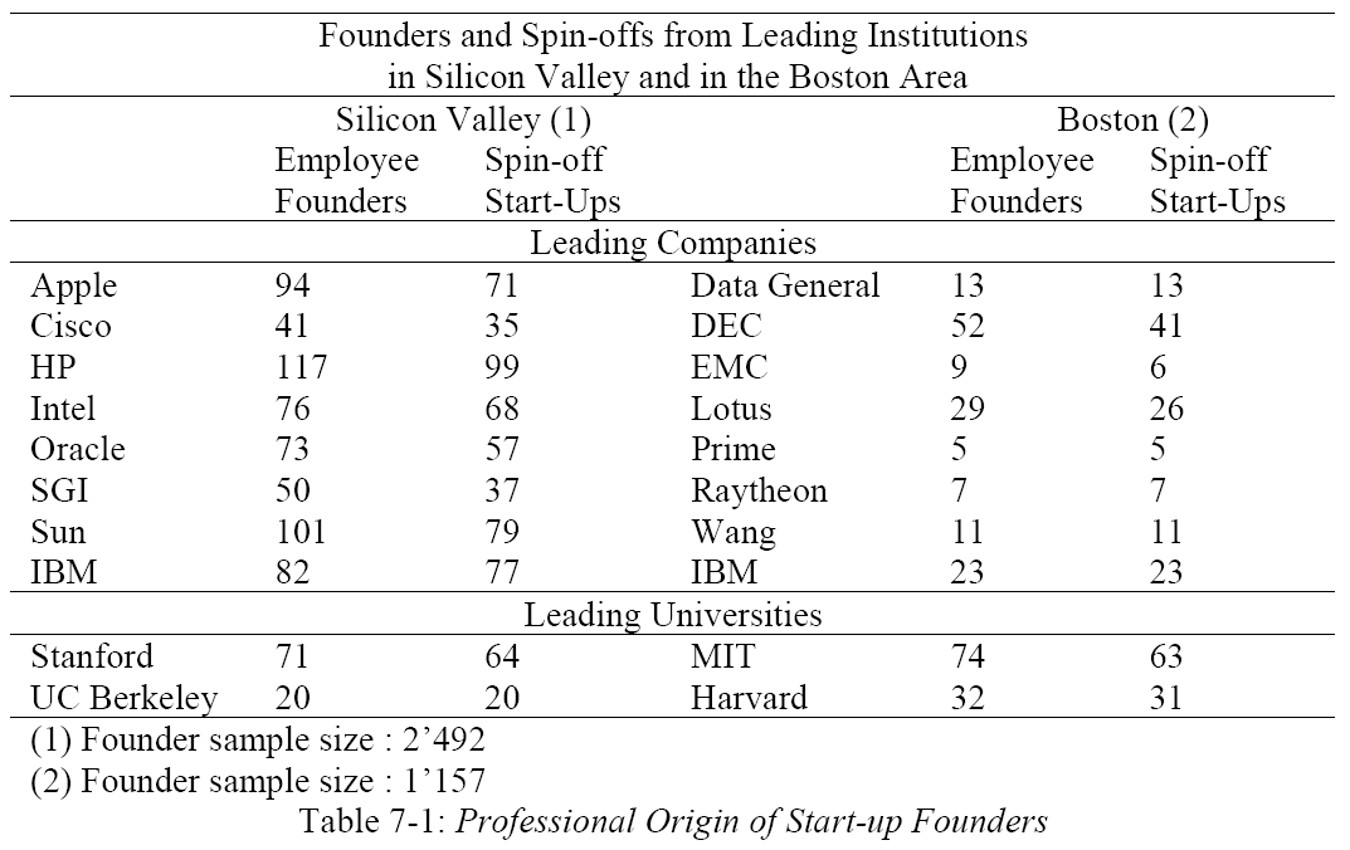

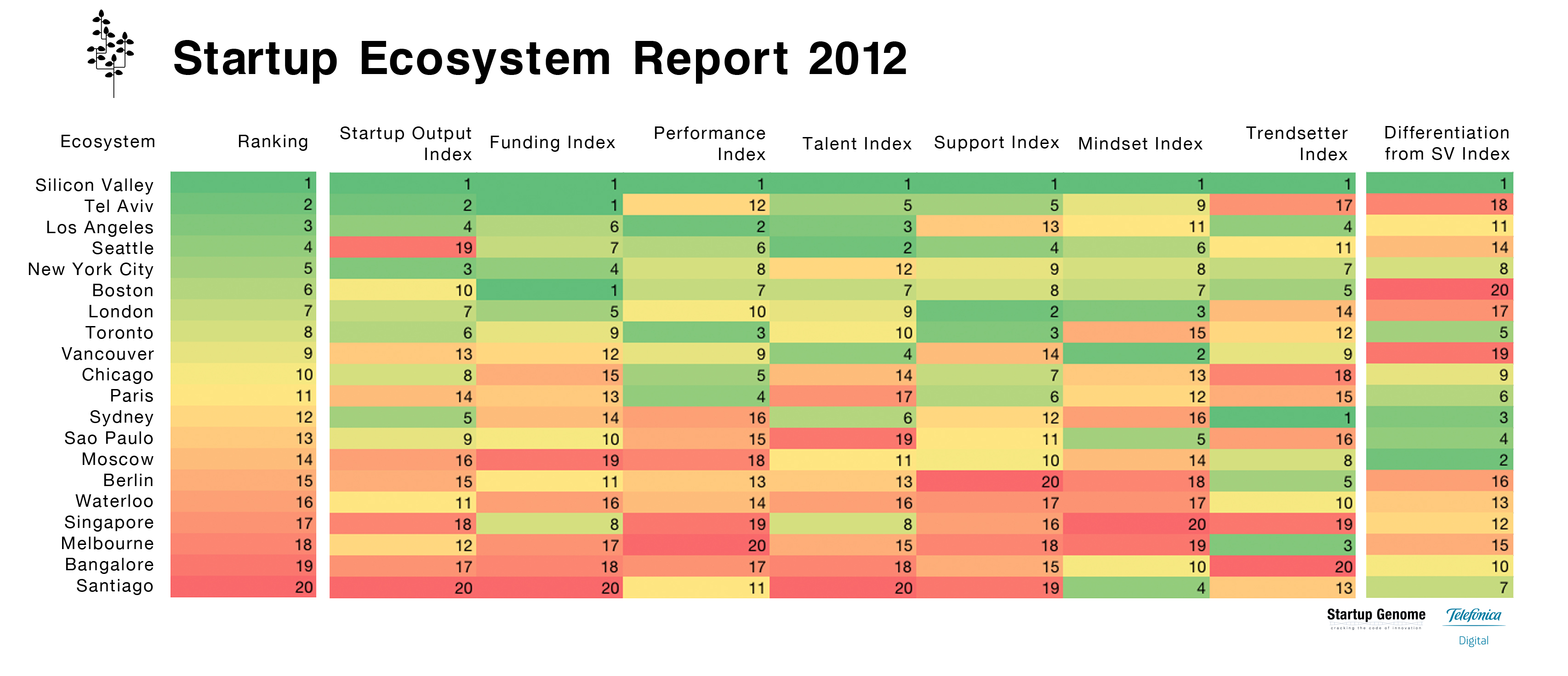

The emergence of Silicon Valley

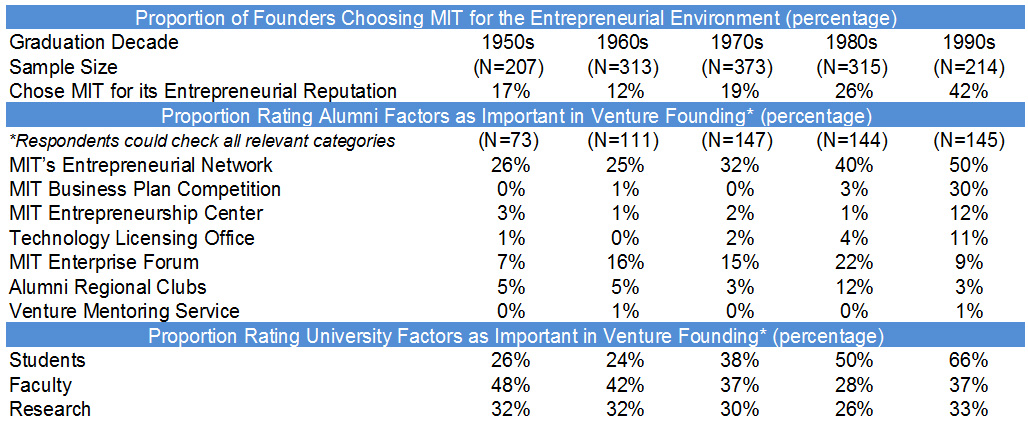

“Today many financiers and entrepreneurs assume the west coast always dominated the VC business. They simply do not realize the industry was pioneered by ARD and a few other northeastern firms in the three decades following World War II. So why did Silicon Valley take over leadership?” [page 227] Spencer Ante explains that with MIT, Harvard, in Boston and New York as the financial capital, the East Coast had a huge lead; but a hospitable climate, ethnic diversity and the vision of Terman at Stanford were critical for the West. “Terman was disturbed to find most of his top students fleeing to the east coast. In 1934, two of his best students, Dave Packard and William Hewlett, followed the same path. Terman wooed them back.” [page 229] Then following Fairchild, semiconductor makers started popping up all over northern California. “All It needed was a steady supply of venture capital.” It’s ironic to read that Tom Perkins declined joining ARD. He wanted to launch his own firm. With Sequoia, Kleiner Perkins would become one of the top 2 VCs in Silicon Valley. The rest is history… ARD was merged with Textron for $400M in 1972. It had made more than $200M in DEC from an initial $70k seed investment.

“In 1978, there were 23 venture funds managing $500 million. By 1983, there were 230 firms overseeing $11 billion. “ [page 250] No doubt, the East Coast missed some of the features that the West would develop with an open culture and the right incentives, in addition to what Doriot pioneered on the East Coast… He dies on June 2, 1987. He was 87 years old.