I had so often heard of this hidden secret of Silicon Valley that when I read about a book written about him, I had to buy and read it immediately. Which I did. And what about the authors: first and foremost, Eric Schmidt, the former CEO of Google…

I had mentioned Campbell 3 times here:

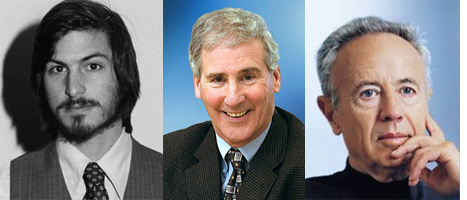

– first in 2014, in Horowitz’ The Hard Thing About Hard Things: there is no recipe but courage. This is there I had Campbell picture just between Steve Jobs and Andy grove.

– then in 2015, in Google in the (Null)Plex – Part 3: a culture. This piece is also mentioned in the new book: Google decide management was not needed any more and neither Schmidt, nor Campbell liked it. Here is how it was solved: “The newly arrived Schmidt and the company’s unofficial executive coach, Bill Campbell, weren’t happy with the idea, either. Campbell would go back and forth with Page on the issue. “People don’t want to be managed,” Page would insist, and Campbell would say, “Yes, they do want to be managed.” One night Campbell stopped the verbal Ping-Pong and said, “Okay, let’s start calling people in and ask them.” It was about 8 P.M., and there were still plenty of engineers in the offices, pecking away at God knows what. One by one, Campbell and Page summoned them in, and one by one Page asked them, “Do you want to be managed?” As Campbell would later recall, “Everyone said yeah.” Page wanted to know why. They told him they wanted somebody to learn from. When they disagreed with colleagues and discussions reached an impasse, they needed someone who could break the ties.”

– finally last year, in Business Lessons by Kleiner Perkins (Part II): Bill Campbell by John Doerr.

Not bad references! I am not finished with the Coach. I have never been a fan of coaching and I am probably wrong. Let me just begin. “I’ve come to believe that coaching might be even more essential than mentoring to our careers and our teams. Whereas mentors dole out words of wisdom, coaches roll up their sleeves and get their hands dirty. They don’t just believe in our potential; they get in the arena to help us realize our potential. They hold up a mirror so we can see our blind spots and they hold us accountable for working through our sore spots. They take responsibility for making us better without taking credit for our accomplishments. And I can’t think of a better role model for a coach than Bill Campbell”. [Page xiv]

On the next page, Schmidt explains he may have missed on important point in his previous book (How Google Works) where he emphasized the importance of brilliant individuals, the smart creatives. And this may be the higher importance of teams, as described in Google’s Project Aristotle. I just give a link form the New York Times about this: What Google Learned From Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team. New research reveals surprising truths about why some work groups thrive and others falter.

The first two chapters are devoted to the life of this extraordinary character. A tireless worker, who started as an American football college coach to become the CEO of high-tech companies such as Claris or Intuit before becoming the Silicon Valley star coach. All told on the occasion of his funerals in 2016. If you do not want to wait for my next blog and not buy the book you may want to read the slideshare from the authors, but first you should read his manifesto, it’s the people.

People are the foundation of any company’s success. The primary job of each manager is to help people be more effective in their job and to grow and develop. We have great people who want to do well, are capable of doing great things, and come to work fired up to do them. Great people flourish in an environment that liberates and amplifies that energy. Managers create this environment through support, respect, and trust.

Support means giving people the tools, information, training, and coaching they need to succeed. It means continuous effort to develop people’s skills. Great managers help people excel and grow.

Respect means understanding people’s unique career goals and being sensitive to their life choices. It means helping people achieve these career goals in a way that’s consistent with the needs of the company.

Trust means freeing people to do their jobs and to make decisions. It means knowing people want to do well and believing that they will.