J’ai souvent des dialogues sur la crise. La crise. Mais crise de quoi? Cette crise financière, économique cache-t-elle autre chose? Une crise de civilisation? Mes collègues me reprochent souvent ma fascination pour le modèle américain qui est peut-être bien à l’origine de cette crise. Alors je vais essayer de contribuer très indirectement à la réflexion en commençant pas la crise de la Science. J’espère que vous allez me suivre!

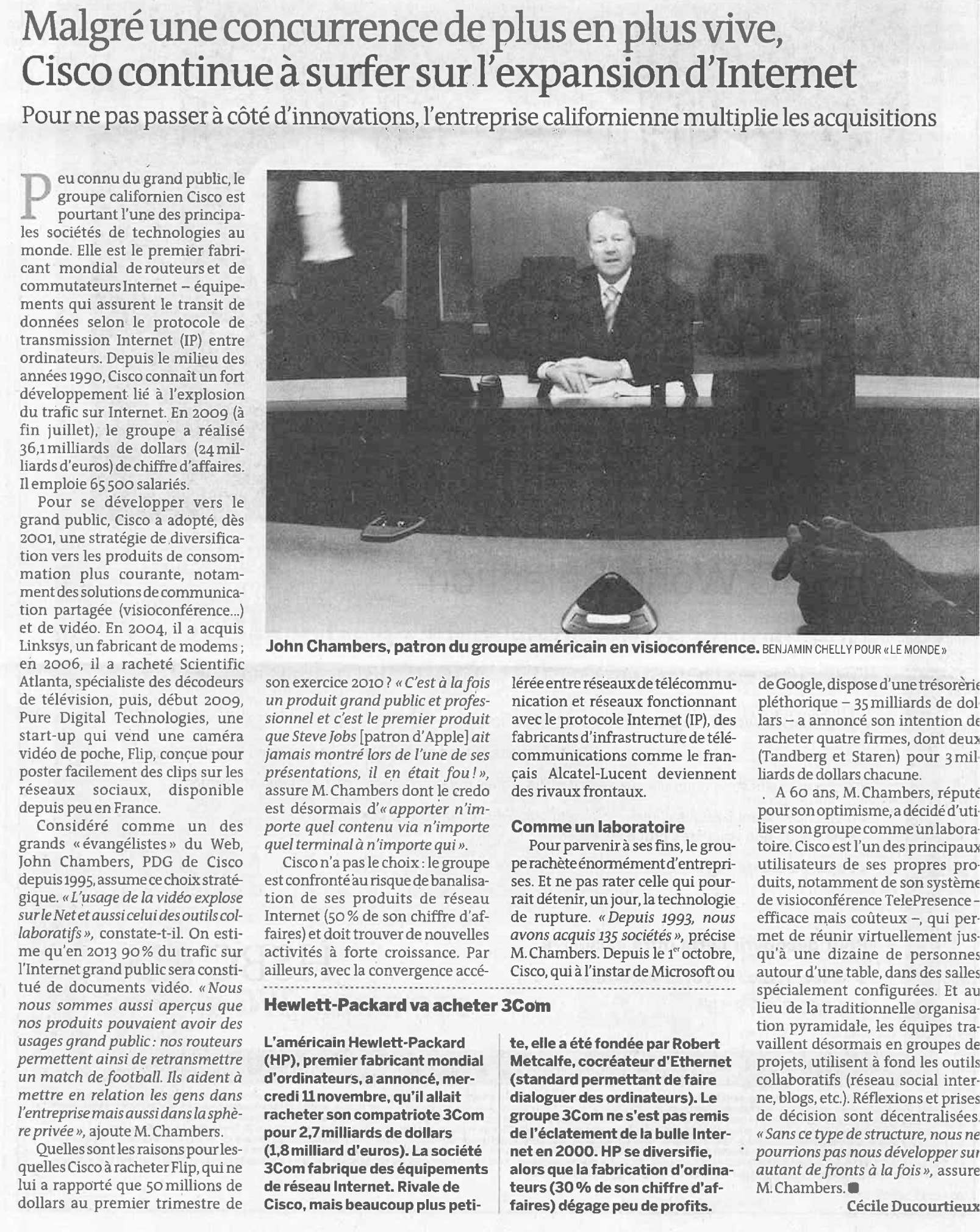

En août 2008, j’écrivais un texte bref sur le sujet à travers le livre de Lee Smolin, Rien ne vas plus en physique. Je viens de lire récemment deux autres ouvrages dont les préoccupations sont proches. Laurent Ségalat a écrit La science à bout de souffle. Cliquez sur le lien qui précède et vous aurez un meilleur descriptif du livre que je ne pourrais le faire.

Libero Zuppiroli publie La bulle universitaire. Faut-il poursuivre le rêve américain?. Il y montre un problème qui commence à se généraliser. Ces derniers jours l’intellectuel français Régis Debray sur France Inter ou le professeur de l’EPFL, Denis Duboule sur la RSR (il faut aller à 22mn15sec environ), se sont eux aussi exprimé l’un sur l’université de la performance et l’autre sur la fraude scientifique. Duboule comme Ségalat compare la pression sur les scientifiques à celle qui pousse les sportifs à se doper. Debray qualifie hier sur France Inter d’asphyxiante cette université de la performance devenue entreprise. Il y expliquait que copier l’Amérique protestante, mélange de temple et de supermarché où Dieu est sur les billets de banque dans une France catholique où l’argent est plus proche de l’enfer risque de faire disparaître le désintéressement, qualité par excellence du service public, de l’université et sans doute de notre culture. Il ajouta qu’une de ses amies, professeur de latin à la Sorbonne, est partie aux USA, faute de « clients en France », parce que « dans les universités américaines, on fait de plus en plus de latin et de grec ». Le constat est plus complexe car un de mes amis, spécialiste de Beaudelaire et professeur aux USA, ne serait pas convaincu que la nouvelle Athènes que serait le nouveau monde est aussi reluisante, quant à la culture classique. Comme quoi, l’enthousiasme réel que j’ai pour certains aspects des USA n’empêche pas (et ne doit pas empêcher) l’esprit critique.

Zuppiroli termine son livre par une postface dont j’extrais un passage:

« La servitude volontaire des masses est encore aujourd’hui le plus grand danger qui guette nos sociétés et menace la paix du monde. C’est le sentiment profond que le plus fort a toujours raison : son succès est la preuve qu’il n’y a pas d’autre choix que de suivre son exemple, car c’est là que se trouve l’espoir. Si les plus forts sont ouvertement injustes, le soutien qu’il convient malgré tout de continuer à leur apporter est ressenti comme une fatalité à laquelle on ne peut échapper.

En principe c’est aux dangers de la servitude volontaire que la culture universitaire, que le travail de pensée devraient permettre de résister pour proposer des solutions nouvelles. »

Je vais sauter du coq à l’âne, ou plutôt au chat… allez voir Les chats persans de toute urgence. La servitude n’y est pas volontaire, dictature obligeant. Mais dans une interview à la revue Positif, le réalisateur Bahman Ghobadi explique que son film l’a libéré. Il n’a plus peur. Et d’ajouter qu’à sa connaissance la censure ne tue plus les cinéastes ou le cinéma aux USA. Modèle pour les uns, repoussoir pour les autres. Cliquez sur ce qui suit pour un intermède musical.

Je vais revenir au point de départ, le coq. Un peu d’égo donc! Je citais Wilhelm Reich en conclusion de mon livre. « Écoute, Petit Homme » est un magnifique essai, petit par la taille, grand par l’inspiration. « Je vais te dire quelque chose, petit homme : tu as perdu le sens de ce qu’il y a de meilleur en toi. Tu l’as étranglé. Tu l’assassines partout où tu le trouves dans les autres, dans tes enfants, dans ta femme, dans ton mari, dans ton père et dans ta mère. Tu es petit et tu veux rester petit. » Le petit homme, c’est vous, c’est moi, c’est nous. Le petit homme a peur, il ne rêve que de normalité, il est en nous tous. Le refuge vers l’autorité nous rend aveugle à notre liberté. Rien ne s’obtient sans effort, sans risque, sans échec parfois. « Tu cherches le bonheur, mais tu préfères la sécurité, même au prix de ta colonne vertébrale, même au prix de ta vie. »

Il me semble que nous avons une crise profonde du collectif et de l’individuel. Comment laisser s’exprimer l’ambition individuelle s’exprimer en enrichissant le collectif. Paradoxalement, le collectif en croyant favoriser l’individuel l’a emprisonné, l’a censuré et le pousse à l’autocensure ou à la fraude. »

La réponse à la crise est difficile. On la trouve en partie chez Zuppiroli. Une utopie universitaire basée sur la créativité et sur l’enseignement, outil de transmission et d’échange. La créativité, l’inventivité et aussi (ou en conséquence?) l’innovation sont, je crois, en crise profonde. Elles sont étouffées par une culture du résultat et de la performance. J’écoutai ce matin un autre point de vue dans le Café philo de la RSR. Rétablir la confiance. La confiance en soi (l’individu) et la confiance réciproque en les autres (le collectif) qui permet respect, transmission et sans doute rapprochement de la tradition et de la nouveauté. « La confiance en soi individuelle peut faire tache d’huile sur le plan collectif ». Il y faudra aussi un esprit critique qui libère de notre servitude et une profonde discussion de nos modèles .

Si vous m’avez suivi jusque là, merci! J’y ai mis beaucoup de conviction. Réagissez, réagissez s’il vous plait.