The new movie about Facebook’s founder, Mark Zuckerberg, is a great movie. It does not matter so much if it is a description of reality. You may watch it as a piece of fiction, and it would remain a great movie thanks to the actors and screenplay.

It is also great because it describes the start-up world in a very accurate manner. It is not a movie about start-ups really, but there are details which reminds me a lot of real-life stories.

The first lesson is that money and friendship seldom work together. The stories of Eduardo Saverin, the founder soon to be diluted, Sean Parker, the exhuberant founder of Napster and Plaxo and mentor of Zuckenberg and the short appearance of Peter Thiel are such examples.

It also shows the old world of Boston where people think ideas are crucial and the new world of Silicon Valley where what matters is implementation. It’s why Silicon Valley is the Triumph of the Nerds. It shows how right Paul Graham is when he says Silicon Valley is about nerds and money. You see the crazy, sad, exciting, depressing life of these hard-working people. You may like it or not, but it is mostly what start-ups are about.

I just looked for what some key people thought of the movie. So, for example, Eduardo Saverin said here: “The Social Network” was bigger and more important than whether the scenes and details included in the script were accurate. After all, the movie was clearly intended to be entertainment and not a fact-based documentary. What struck me most was not what happened – and what did not – and who said what to whom and why. The true takeaway for me was that entrepreneurship and creativity, however complicated, difficult or tortured to execute, are perhaps the most important drivers of business today and the growth of our economy.”

And Dustin Moskovitz said there: It is interesting to see my past rewritten in a way that emphasizes things that didn’t matter (like the Winklevosses, who I’ve still never even met and had no part in the work we did to create the site over the past 6 years) and leaves out things that really did (like the many other people in our lives at the time, who supported us in innumerable ways). Other than that, it’s just cool to see a dramatization of history. A lot of exciting things happened in 2004, but mostly we just worked a lot and stressed out about things; the version in the trailer seems a lot more exciting, so I’m just going to choose to remember that we drank ourselves silly and had a lot of sex with coeds. […] I’m very curious to see how Mark turns out in the end – the plot of the book/script unabashedly attack him, but I actually felt like a lot of his positive qualities come out truthfully in the trailer (soundtrack aside). At the end of the day, they cannot help but portray him as the driven, forward-thinking genius that he is. And the Ad Board *does* owe him some recognition, dammit.

And Zuckerberg himself!

Watch live video from c3oorg on Justin.tv

This is from Garham’s start-up school and here is part 2

Watch live video from c3oorg on Justin.tv

Of course, this looks like corporate language, we should remember these guys have FaceBook shares! Talking about shares, there was another thing I did not like recently, the fact that according to Forbes, Zuckerberg would be richer than Steve Jobs. I had a discussion with a friend over the week end and he agreed with the statement whereas I disagreed. It may be a detail: but as long as Facebook is not quoted, Zuckerberg’s wealth is mostly paper value he can not really trade. I am sure he is already rich, he probably has already monetized some of his shares but not all of them whereas Jobs owns shares which are liquid. It may not be a big difference given the success of Facebook, but I have seen to many stories of start-ups where people thought the paper value of the stock was real wealth and the next day worth nothing…

When my daughter told me yesterday, she might at least explain her friends what her dad was doing. i.e. working in the world of start-ups, I thought the movie had at least reached that goal of reaching a large audience towards this important topic!

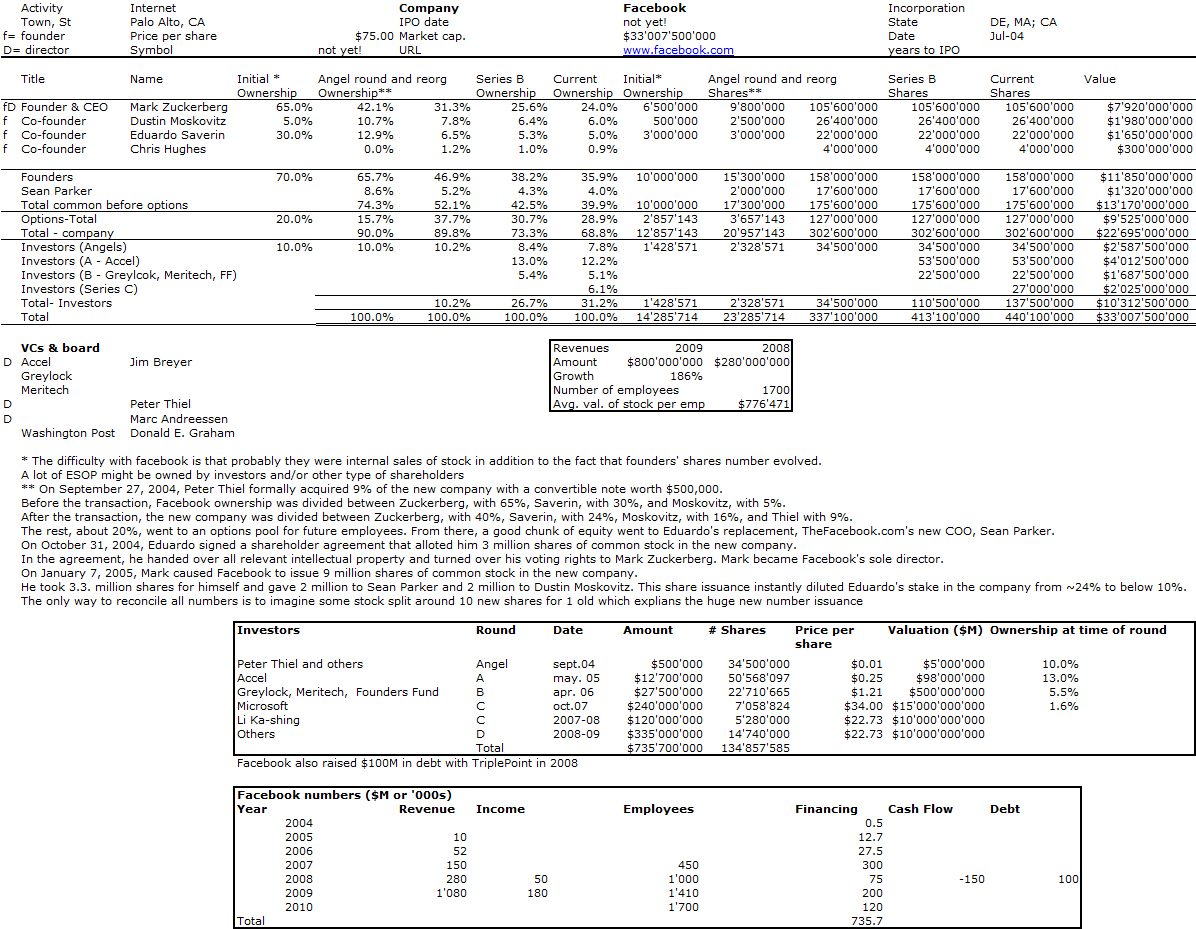

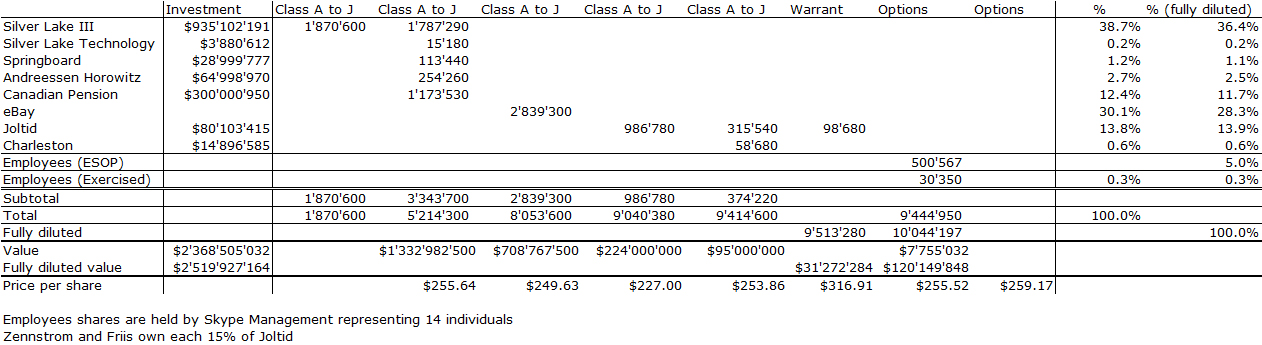

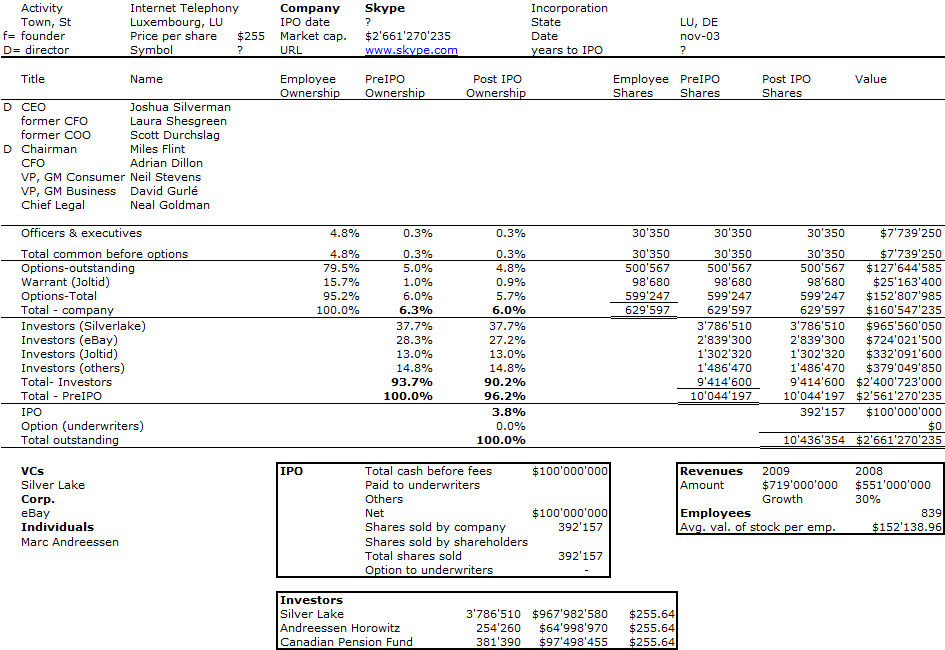

Final point, a recurrent topic in my blog: Facebook cap. table and shareholder structure. As Facebook is private, it is a challenge to know what’s true and what’s myth. I have still tried the exercice from what the Internet gives. One interesting feature is Saverin’s dilution from 30% to 5% whereas Zuckerberg went from 65% to 24%, not really pro-rata! We shall see when Facebook goes public, who wrong I was!