While in Antwerpen (Belgium) where I gave a workshop related to my vision of Silicon Valley described in the book Start-up, I had the nice opportunity (thanks Walter 🙂 ) to meet with Sven De Cleyn whose PhD thesis was published as a very interesting book: The early development of academic spin-offs : holistic study on the survival of 185 European product-oriented ventures using a resource-based perspective. The conversation I had with him convinced me I had to read his work. Although I am not sure I would advise anyone to do so (sorry Sven 🙁 but it is also 335 pages of dense content, including tables and statistical analyses), it is a great piece of work.

I had not seen before such work based on European spin-offs. Of course there is the American equivalent with Shane’s work, Academic Entrepreneurship: University Spinoffs And Wealth Creation and also lesser known but probably as good, the multiple papers of Junfu Zhang, including Entrepreneurship among Academics: A Study of University Spin-offs Using Venture Capital Data. But on the European side?

So let me summarize what I learnt. First an academic spin-off (ASO) is defined as “[1] a new legal entity (company) [2] founded by one or more individuals from an academic parent organization [3] to exploit some kind of knowledge [4] gained in the academic parent organization and transferred to the new company”. Then Sven studied two main questions:

– Research question 1

What characterizes the early development process of knowledge-intensive product-oriented academic spin-offs?

– Research question 2

What are the major criteria that determine the outcome of this process?

And he used 4 main theoretical frameworks (remember, it is a PhD thesis). I quote him again:

– the Resource-Based View of the firm (RBV), which posits that firm can only achieve a sustainable competitive advantage if they possess valuable, rare, inimitable and non-substitutable resources

– the Human Capital Theory (HCT), which explains firm survival and performance in terms of the firm’s knowledge, skills and experience, which can be created and accumulated through education, training and other experiences

– the Social Capital Theory. The central tenet suggests that a firm’s survival and performance are dependent upon the network to which it has access. The difference between SCT on one hand and RBV and HCT on the other, is that social capital, unlike other resource types, is not located within a firm but in the relationship with other actors

– the fourth and last theoretical stream relates to Life Cycle Models (LCMs). A firm’s resource needs are different in the first years after foundation when compared to more mature phases. The LCM theory builds upon the biological evolution of a living organism, where firms evolve through a number of distinct and consecutive stages and in the transition between the stages a number of important hurdles or junctures have to be overcome.

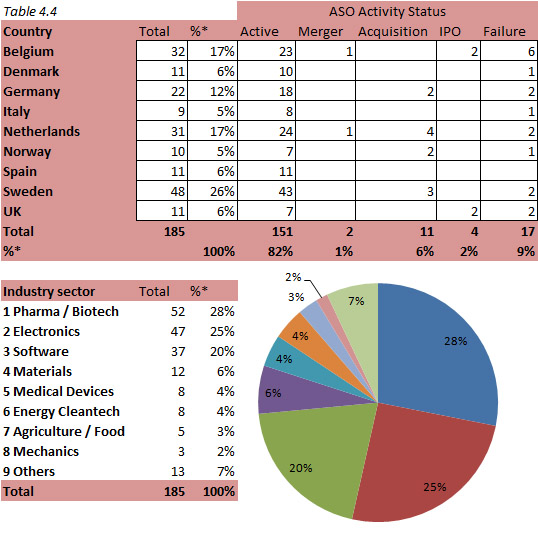

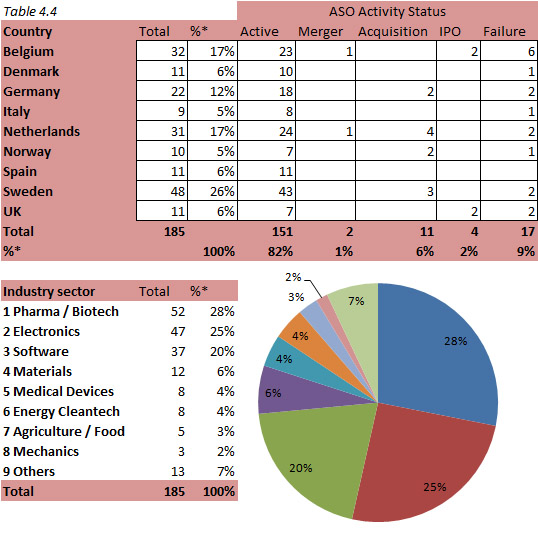

The heart of the dissertation is formed by a quantitative part. The first phase concerns the actual data collection, using personal interviews (in person, by telephone or using Skype) with 185 top managers (preferably one of the active founders) in nine European countries.

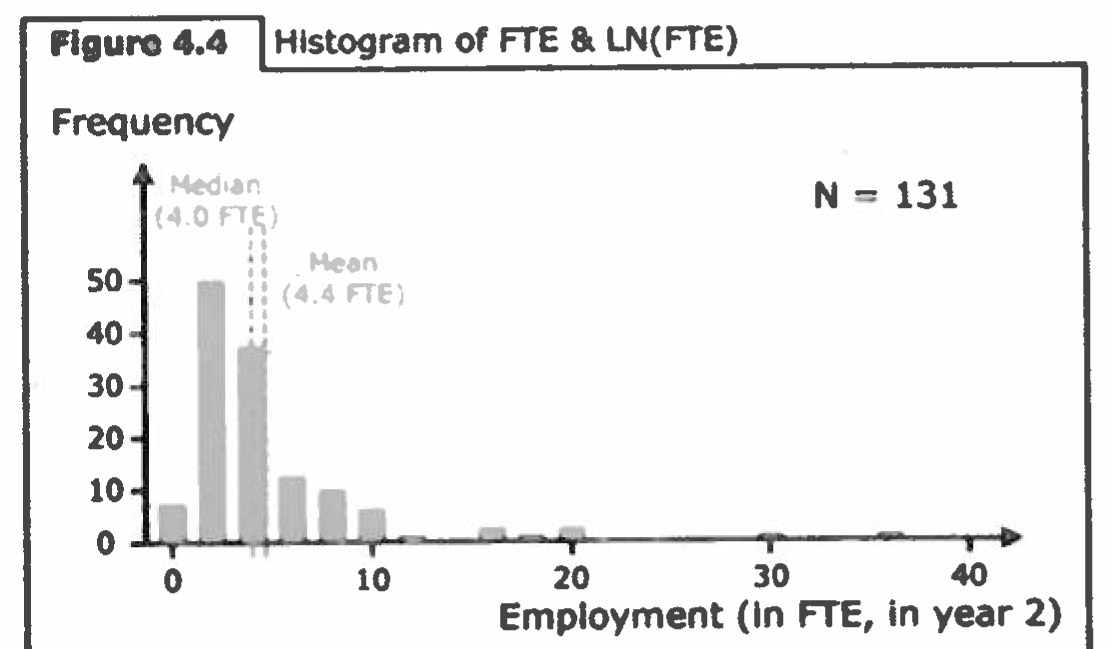

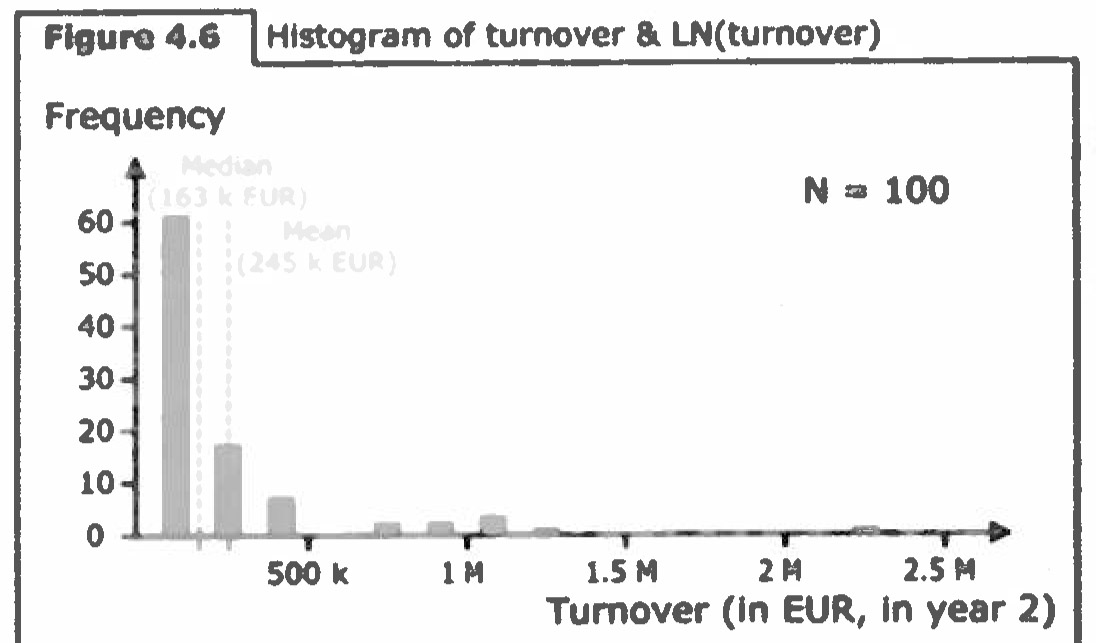

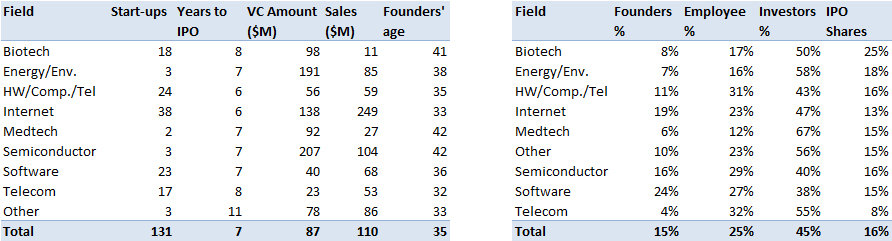

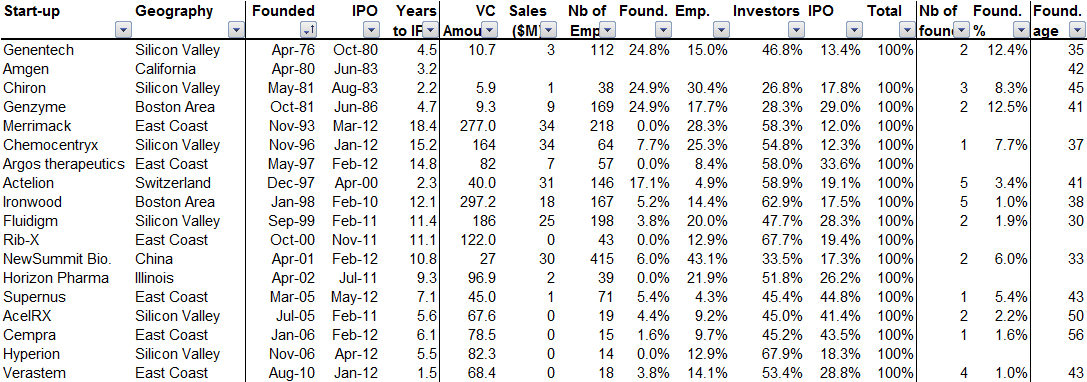

In addition here are some more figures about these spin-offs. Not surprisingly (for me!) the employment and turnover are not very high:

Some interesting not to say surprising results include:

+ on the Business side:

– The results of this study confirm that having developed a formal, written business does not contribute significantly to ASO survival probability.

– However, the results also indicate that several important constituent sections of a business plan (e.g. market study, production analysis …) contribute positively to survival likelihood.

– If the founders of the ASO have discussed the first drafts of the business plan with other entities (mostly externals), subsequent ASO survival chances might be affected. The analyses reveal that ASOs whose business plan has been screened, challenged and altered by risk capital providers face an increased failure risk.

– The results indicate ASOs using patents to protect their core technology do not necessarily enjoy higher survival probability.

– The results indicate that product development teams with (potential) customers aboard increase ASO survival likelihood substantially.

+ on the team side:

– Prior entrepreneurial experience (whether in a high-tech venture or not) has a significant positive impact, but this effect disappears and becomes negative for serial entrepreneurs. The latter result is ascribed to entrepreneurial euphoria (successful entrepreneurs tend to search less for relevant information in subsequent new initiatives).

– Heterogeneous team, which are composed of a mixed background, contribute significantly and in a positive way to ASO success probability.

– In first instance, an ongoing active involvement of at least one of the (key) founders has a significant positive effect on ASO survival probability. However, some additional tests reveal that preferably this involvement does not occur as CEO. Secondly, a long-term and strong representation of the founders in the shareholder structure (meaning a shareholdership of at least 50% for the entire group of founders) appears to significantly enhance ASO survival likelihood.

+ about stakeholders:

– The origin of financial resources has no significant impact on its subsequent success (i.e. risk capital does not increase success likelihood when compared to any other funding source). On the other hand, ASOs able to attract subsidies for the development of their business, technology or product have significantly better survival odds than ASOs who don’t.

– Academic continued, long-term support (at least up till the moment of interview) turns out to have a positive and significant impact on ASO success probability.

– In the first place, the results have pointed to the importance of the timing of ASO foundation, as ASOs who developed at least a β-prototype at the time of foundation have significantly higher survival odds.

A couple more quotes that I found striking:

– [page 16] European ASOs are reported to be small-scale ventures (mostly one-man SMEs) with limited growth ambitions and clear visions. Yet, the main contribution of ASO does not lie in a fast organic growth, but rather in its contribution to the transfer of technologies and knowledge throughout their networks and in a reasonable rentability. (This is not a result of De Cleyn, but his own analysis of past research)

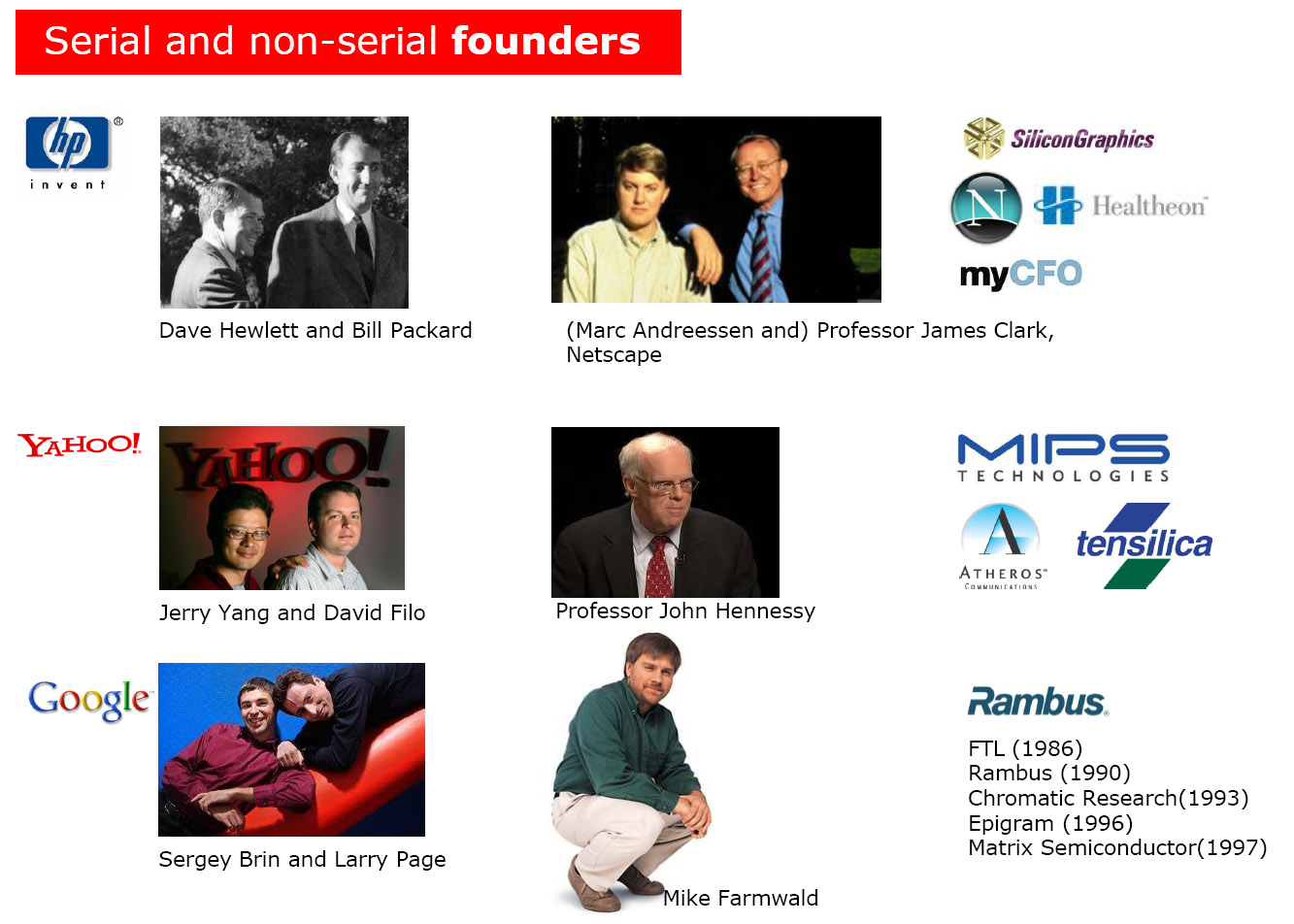

– [page 52] Founding teams seem to perform better than individual founders. They tend to experience less failure, more mergers and/or acquisitions and a larger employment growth. This superior performance might be due to a better access to resources and network relationships than solo start-ups have. (Same remark)

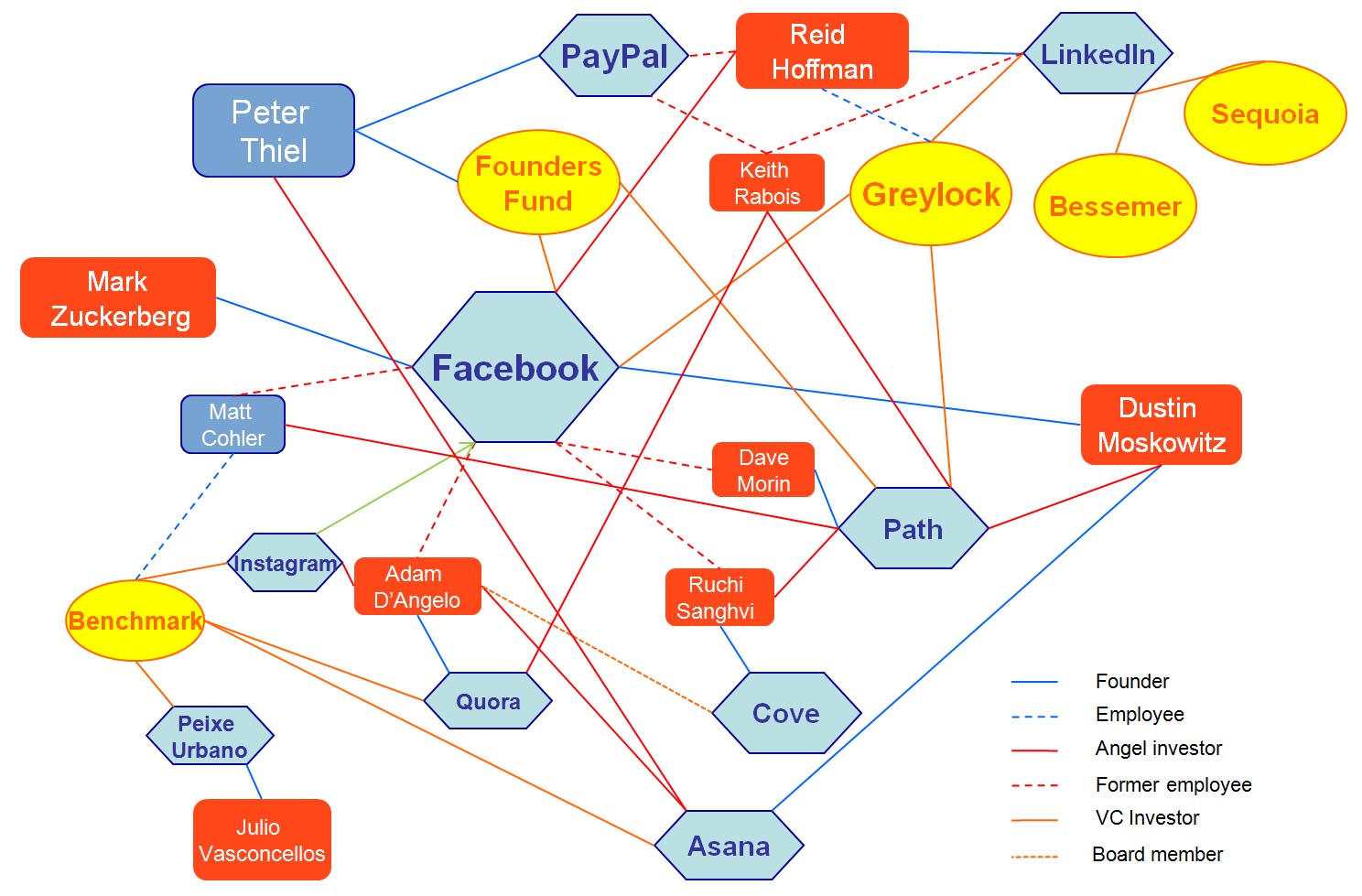

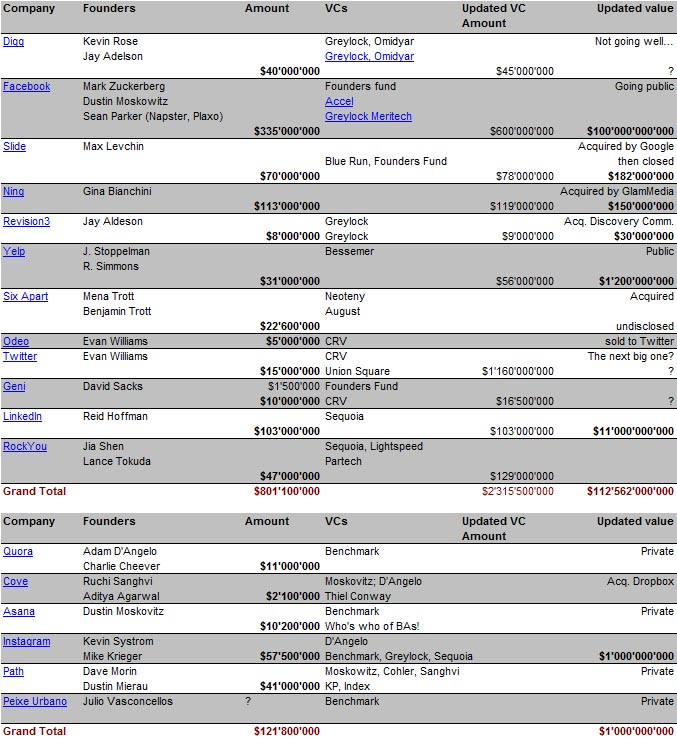

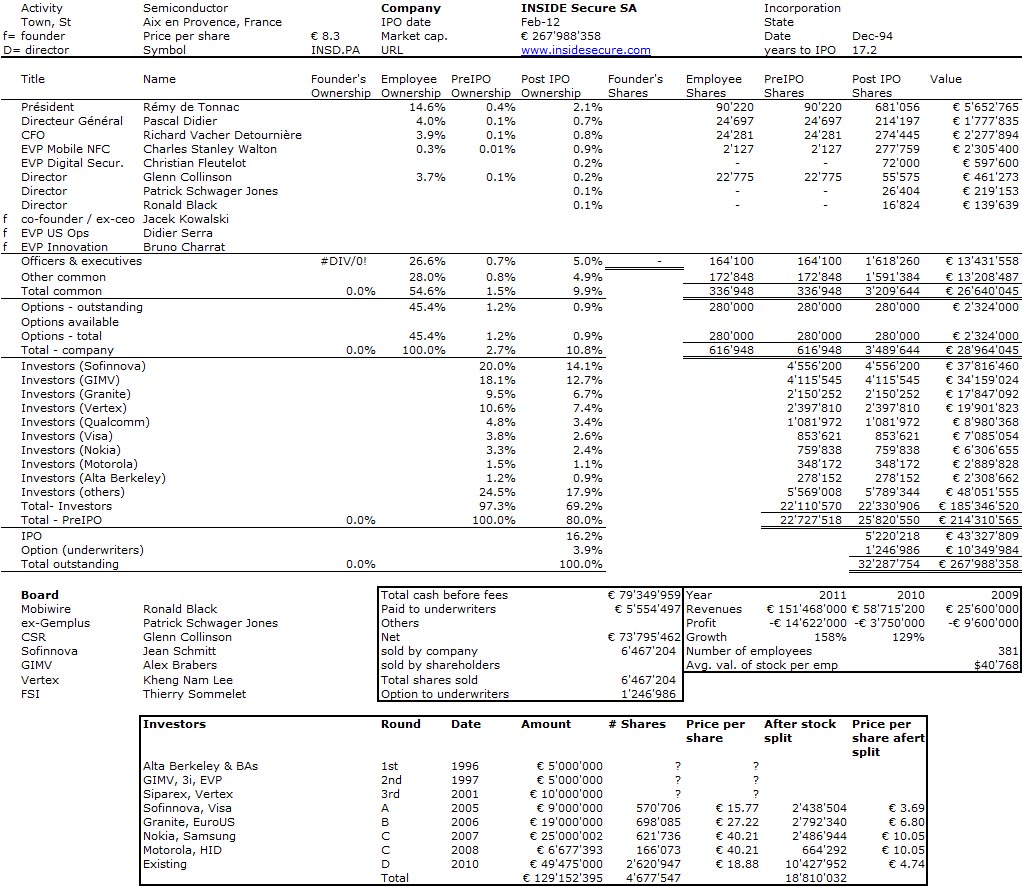

Now some personal comments. First the lessons are much richer than this short summary. So if you have an interest in the topic, you should read De Cleyn’s book. But most importantly, for me, it dramatically shows some critical differences between the European and the American scene, at least the scene I know well, Silicon Valley. Sven De Cleyn’s definition of success is basically (I hope I am correct) the opposite of failure, which for example implies that surviving is considered as success. I am not sure it is the vision Americans have (the famous Fail Fast that entrepreneurs use even independently of the objectives of venture capital, which hates nothing more than “living-dead”.) You might be interested in comparing Sven’s data with my own analysis of Stanford related start-ups. A last comment. I asked Sven why he did not cover licensing deals with universities. The answer was twofold. He already had enough material to cover and the topic is more sensitive than others. I agree!

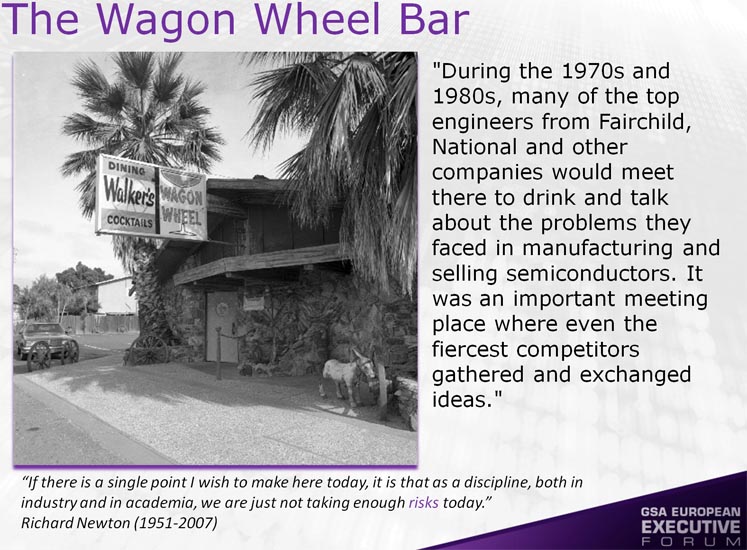

As a short summary, I had not seen such a deep analysis of European start-ups, with so much statistical analysis. And… unfortunately, it seems to confirm the culture gap we have with the USA. It might be that we have a different way of doing things or it might be that we have not really understood what Silicon Valley is really about…