I regularly compile data on start-ups with shares of founders, employees, board members investors, as well as the size of the round of financings. These are companies who went public or at least filed to go public or were acquired. Enjoy!

I regularly compile data on start-ups with shares of founders, employees, board members investors, as well as the size of the round of financings. These are companies who went public or at least filed to go public or were acquired. Enjoy!

Thanks to my friend Jean-Jacques for pointing to a nice historical article about the beginnings of Silicon Valley. According to The First Trillion-Dollar Startup, “measured in today’s dollars, we believe the firm [ Fairchild ] would qualify as the first trillion dollar startup in the world.” I will let you read the other findings and will not relate again a story I mentioned in The fathers of Silicon Valley: the Traitorous Eight.

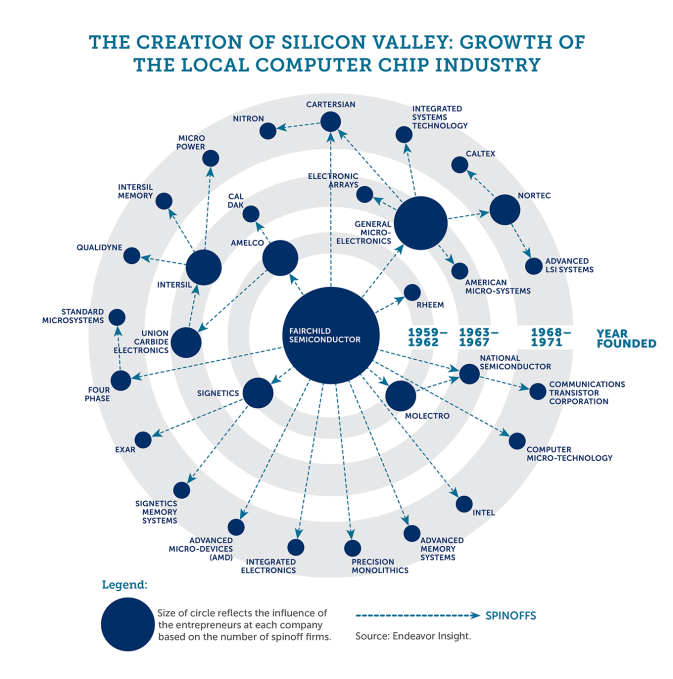

The authors show that Silicon Valley did not exist in 1957. No company active in semiconductor was based there as the East Coast was still the center of high-tech. But the founders of Fairchild are directly or indirectly responsible for 92 companies in Silicon Valley, today listed on Nasdaq or NYSE, worth over $2’000 billion and employing more than 800,000 people.

Here is a nice illustration of their study,

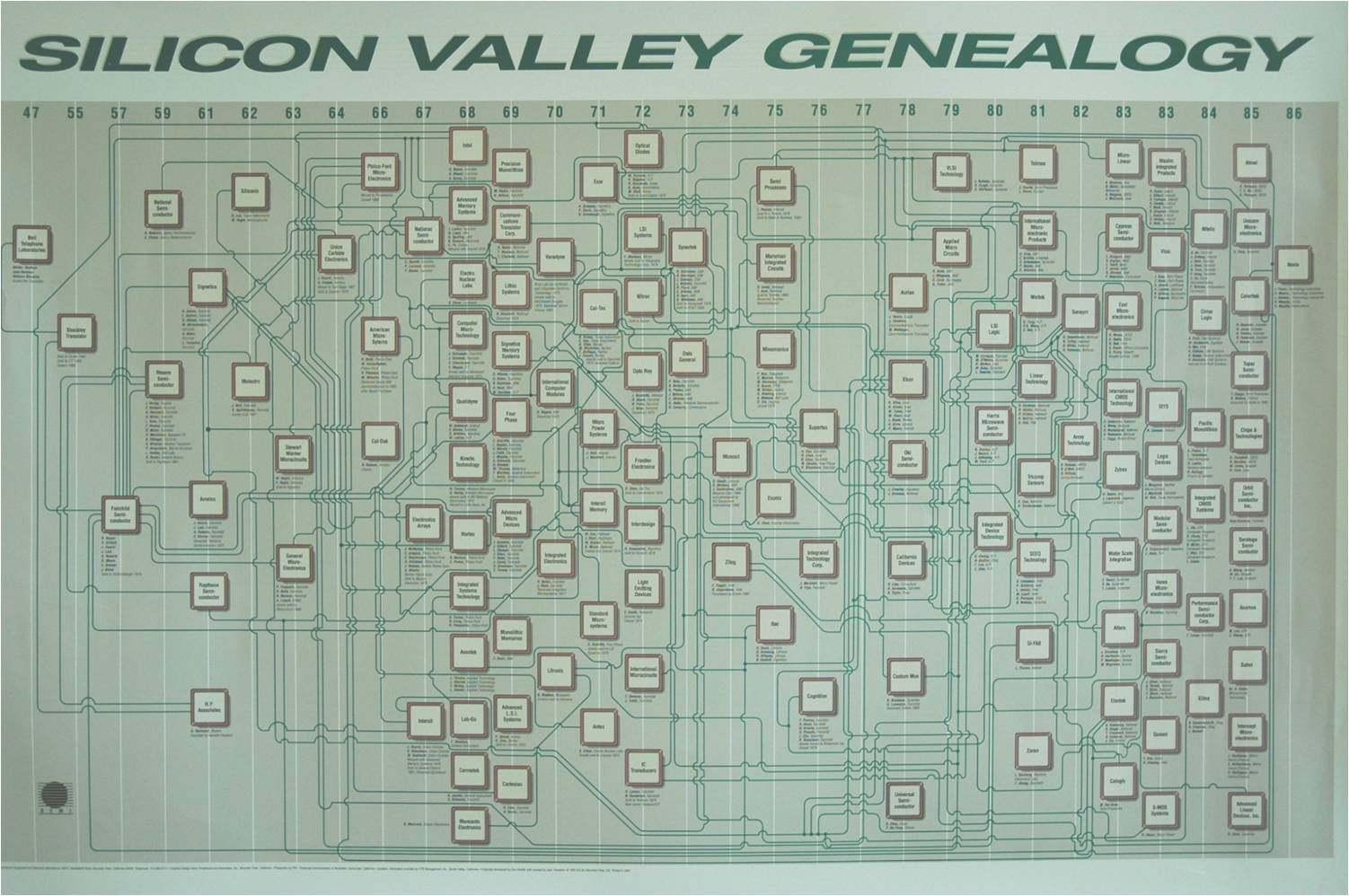

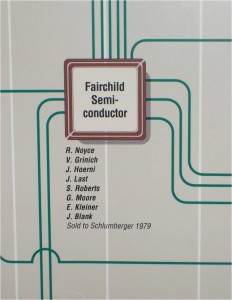

but I still love this one, a famous poster created by the author of the term Silicon Valley; I scanned it a few years ago,

the image below is taken from the previous (left and halfway up – corresponding to 1957)

The full report can be downloaded in pdf format and I find interesting their 3 lessons:

1. Great companies can develop in unlikely and challenging places.

2. A few entrepreneurs can make a large impact.

3. There is a framework for success that leaders can accelerate: ambition, growth, commitment, reinvestment.

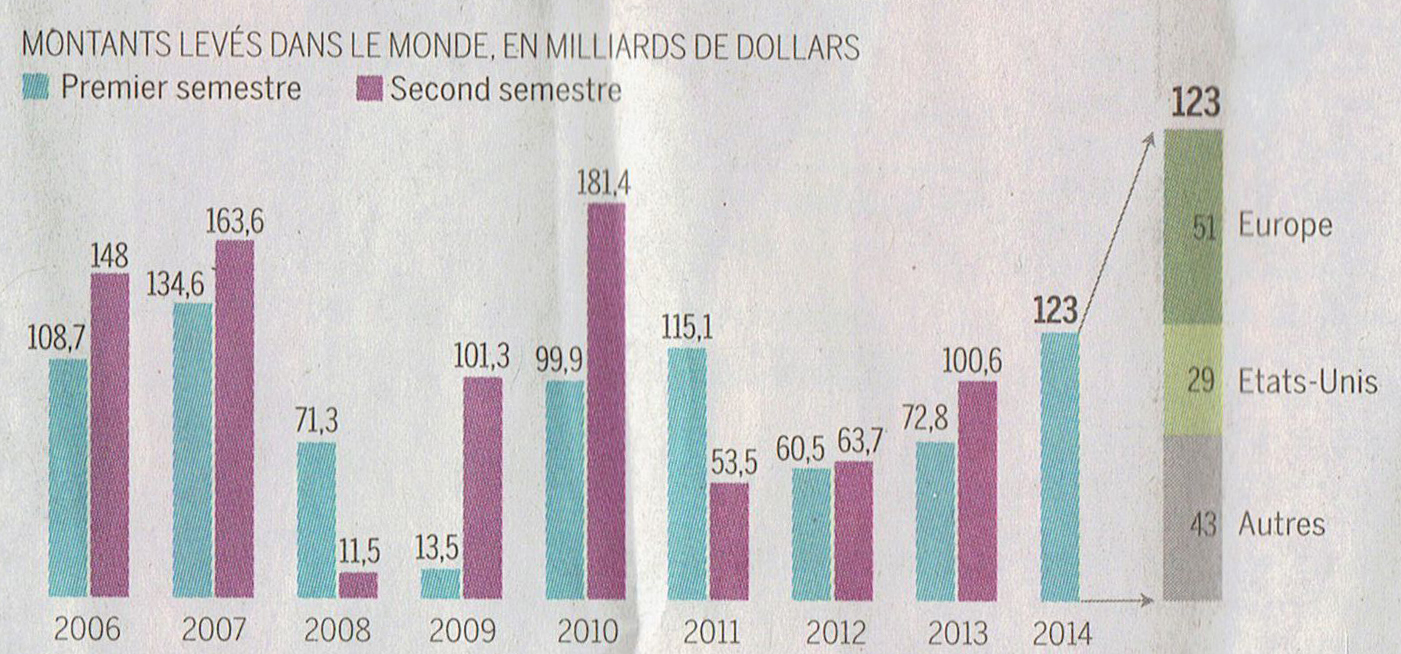

I just read an excellent article in the newspaper Le Monde: Investors get tired of IPOs.

The first reading could suggest positive news, as shown in the following charts:

Click to enlarge

I looked in more detail at the IPO prospectus of 11 of these strat-ups. For reference, the 11 companies studied are:

Ask http://www.ask-rfid.com

Awox http://www.awox.com

Crossject http://www.crossject.com

Fermentalg http://www.fermentalg.com

Genomic Vision http://www.genomicvision.com

Genticel http://www.genticel.com

Mcphy energy http://www.mcphy.com

Supersonic Imagine http://www.supersonicimagine.fr

Txcell http://www.txcell.com

Viadeo http://fr.viadeo.com/fr/

Visiativ http://www.visiativ.com

and here I let you discover the 11 capitalization tables.

I show you here the two most successful and Supersonic Viadeo:

Why did I feel the need to use the term “sad” situation? Because:

– Valuations do not exceed €200M

– Amounts raised do not exceed €50M

With such numbers, neither entrepreneurs nor investors can not be compared with their U.S. counterparts. (I refer you to my summary of U.S. IPOs, if you are not convinced).

And if you’re still not convinced, I refer you to an excellent debate on France Culture including Osamma Ammar, founder of The Family: Is France heaven or hell for start-ups? Osamma Ammar describes the historical weaknesses of the French system, too much government intervention, IPOs (like those Viadeo rightly) that are so low that they would not take place in the USA (whereas a French start-up such as Criteo could be quoted on the Nasdaq). There is much to say from the 11 IPOS, but I leave you to think about what they mean …

My friend Jean-Jacques (thanks :-)) sent me a link about the CNBC Disruptor 50, a list of 50 “private companies in 27 industries — from aerospace to enterprise software to retail — whose innovations are revolutionizing the business landscape”. One could criticize the method, the fields, what is disruptive and what is not, but the list is by itself interesting. And I have done a few quick and dirty analyses. (I mean by Q&D a very fast analysis on the age of founders based on available data – their age or the year of their bachelor – my full analysis is available at the end of the post)

I found the following:

– Disruptive innovators are young (33 years-old)

– They raise a lot of money: more than $200M!!!

– and yes, they are mostly based in Silicon Valley.

Disruptive innovators are young

The average age of founder is 33 (whereas the age of founders of start-ups is closer to 39 – see my recent post Age and Experience of High-tech Entrepreneurs). As it was the case with that general analysis, founders in biotech and energy are much older than in software or internet. This was something I had already addressed in that paper: disruption might be the field of young creators.

They raise a lot of money

A really striking point is the amount of money raised by these disruptive companies. With an average age of 6 years, these companies have raised on average $200M… In energy, it is more than $400M and even more than $250M for the internet.

Silicon Valley leads

Not surprisingly though, Silicon Valley seems to be the place where to be. 27 companies are based there (a little more than 50%). It is also where they have access to the most capital ($280M on average). Then comes the East Coast (25%). Surprisingly they are based in NYC, not in Boston anymore when East Coast is concerned. Only 3 are Europeans… (Spotify, Transferwise and Fon) even if a few Europeans have also moved to SV…

Here is my full analysis which as I said before might contain mistakes (particularly on the founders’ age…). You might also disagree with my field classification…

Serial entrepreneur is a buzz word. I have never been convinced by the link between serial entrepreneur and success. I even made an analysis for the ones linked to Stanford University (check Serial entrepreneurs: are they better?). But from time to time, you see such amazing and rare success stories.

Andy Bechtolsheim (left) and David Cheriton (right) [with Arista’s co-founder, Ken Duda).

Andy Bechtolsheim‘s is a Silicon Valley icon. In 1982, he co-founded Sun Microsystems. Born in Germany in 1995, he moved to the USA at age 20 for his master at CMU. He moved to Silicon Vallley to work at Intel but ended up at Stanford for his PhD. Sun came thereafter. He stayed there until 1995…

David Cheriton is a Stanford professor. Born in 1951, he got his BS from UBC and his PhD from the University of Waterloo. He moved to Stanford in 1981. I am not sure how they met, but they co-founded Granite Systems in 1995. A year later, it was bought by Cisco for $220M. Bechtolsheim stayed with Cisco until 2003. Cheriton is still a Stanford professor. Two years later, they met with two unknown Stanford students, Larry Page and Sergei Brin. Both invested $100’000 each in their start-up, but this is another story…

In February 2001, they co-founded another networking start-up, Kealia. In April 2004, “Sun issued an aggregate of approximately 20,000,000 shares of common stock (including assumed options) in exchange for all outstanding stock and options of Kealia” (Newswire reference). At that time, Sun’s share was worth about $4, so it would have been an $80M acquisition. That same year, Google went public (on August 19) at $85/share. They had received 1’600’000 shares for their $100k investment (i.e. $0.0625 per share, a multiple of 1’360 and with a six month lock-up, the share value more than doubled…) The Kealia success is all but relative…

Granite might have had a logo, but I could not find it on the web. Kealia was apparently always in stealth mode. No logo available either

But it did not stop them. In October 2004, they co-founded Arista Networks. The name at the time was Arastra. The company just went public which is the motivation for this post. My usual cap. table follows. And because they made so much money, the two serial entrepreneurs nearly funded it entirely… Not the smallest success of all!

PS: Are Cheriton and bechtolsheim good friends? I have not clue, but the Arista IPO document mentions a litigation:

On April 4, 2014, Optumsoft filed a lawsuit against us in the Superior Court of California, Santa Clara County titled Optumsoft, Inc. v. Arista Networks, Inc., in which it asserts (i) ownership of certain components of our EOS network operating system pursuant to the terms of a 2004 agreement between the companies, and (ii) breaches of certain confidentiality and use restrictions in that agreement. Under the terms of the 2004 agreement, Optumsoft provided us with a non-exclusive, irrevocable, royalty-free license to software delivered by Optumsoft comprising a software tool used to develop certain components of EOS and a runtime library that is incorporated into EOS. The 2004 agreement places certain restrictions on our use and disclosure of the Optumsoft software and gives Optumsoft ownership of improvements, modifications and corrections to, and derivative works of, the Optumsoft software that we develop.

In its lawsuit, Optumsoft has asked the Court to order us to (i) give Optumsoft copies of certain components of our software for evaluation by Optumsoft, (ii) cease all conduct constituting the alleged confidentiality and use restriction breaches, (iii) secure the return or deletion of Optumsoft’s alleged intellectual property provided to third parties, including our customers, (iv) assign ownership to Optumsoft of Optumsoft’s alleged intellectual property currently owned by us, and (v) pay Optumsoft’s alleged damages, attorney’s fees, and costs of the lawsuit. David Cheriton, one of our founders and a former member of our board of directors who resigned from our board of directors on March 1, 2014 and has no continuing role with us, is a founder and, we believe, the largest stockholder and director of Optumsoft. The 2010 David R. Cheriton Irrevocable Trust dtd July 27, 2010, a trust for the benefit of the minor children of Mr. Cheriton, is our largest stockholder.

Optumsoft has identified in confidential filings certain software components it claims to own, which are generally applicable tools and utility subroutines and not networking specific code. We cannot assure which software components Optumsoft may ultimately claim to own in the litigation or whether such claimed components are material.

On April 14, 2014, we filed a cross-complaint against Optumsoft, in which we assert our ownership of the software components at issue and our interpretation of the 2004 agreement. Among other things, we assert that the language of the 2004 agreement and the parties’ long course of conduct support our ownership of the disputed software components. We ask the Court to declare our ownership of those software components, all similarly-situated software components developed in the future and all related intellectual property. We also assert that, even if we are found not to own any particular components at issue, such components are licensed to us under the terms of the 2004 agreement. However, there can be no assurance that our assertions will ultimately prevail in litigation.

On the same day, we also filed an answer to Optumsoft’s claims, as well as affirmative defenses based in part on Optumsoft’s failure to maintain the confidentiality of its claimed trade secrets, its authorization of the disclosures it asserts and its delay in claiming ownership of the software components at issue. We have also taken additional steps to respond to Optumsoft’s allegations that we improperly used and/or disclosed Optumsoft confidential information. While we believe we have strong defenses to these allegations, we believe we have (i) revised our software to remove the elements we understand to be at issue and made the revised software available to our customers and (ii) removed information from our website that Optumsoft asserted disclosed Optumsoft confidential information.

We intend to vigorously defend against Optumsoft’s lawsuit. However, we cannot be certain that, if litigated, any claims by Optumsoft would be resolved in our favor. For example, if it were determined that Optumsoft owned components of our EOS network operating system, we would be required to transfer ownership of those components and any related intellectual property to Optumsoft. If Optumsoft were the owner of those components, it could make them available to our competitors, such as through a sale or license. In addition, Optumsoft could assert additional or different claims against us, including claims that our license from Optumsoft is invalid. Additionally, the existence of this lawsuit could cause concern among our customers and potential customers and could adversely affect our business and results of operations. An adverse litigation ruling could also result in a significant damages award against us and the injunctive relief described above. In addition, if our license was ruled to have been terminated, and we were not able to negotiate a new license from Optumsoft on reasonable terms, we could be required to pay substantial royalties to Optumsoft or be prohibited from selling products that incorporate Optumsoft intellectual property. Any such adverse ruling could materially adversely affect our business, prospects, results of operation and financial condition. Whether or not we prevail in the lawsuit, we expect that the litigation will be expensive, time-consuming and a distraction to management in operating our business.

We do not believe a loss is probable; however, it is reasonably possible. Due to the early stage of this matter, no estimate of the amount or range of possible amounts can be determined at this time.

Every other year I go to BCERC, an academic conference about entrepreneurship. Not only to listen to researchers but also to add my own contribution. (You can find my previous contributions with tag BCERC). It’s also a way to confront and share ideas and results with others. This year, I wrote a short paper about Age and Experience of High-tech Entrepreneurs. The slides are available on slideshare and here they are:

The paper is available on SSRN. Why did I do this, well, you can have a look at the slides or even read the 15-page paper. But my point was to react to recent claims that high-tech entrepreneurs are on average about 40-year old. I was surprised and did my own analysis based on about 570 founders… and yes, the average age is about 38. But… the devil is in the details. It is sector-, time-, region- dependant. And even more surprisingly, the higher the value creation, the younger the founders. here are just a few tables as a quick conclusion…

GoPro just filed to go public (check here its SEC S-1 document). Its founder Nick Woodman is so unconventional that he is called the Mad Billionaire.

But what is really unconventional is the fact that a hardware company can still go public in the social media era. There are other unconventional features, particularly in the shareholding. Its founder and his father own together more than 40% of the company. The first developer still owns about 5%. Of course, the investors do not have as much… Silicon Valley is also known for the network strength so how is it a surfer could get the attention of the region? Because the GoPro cameras are great! Well this might not be all… Irwin Federman is a legendary VC, shareholder in GoPro… and Woodman’s stepfather…

Two EPFL entrepreneurs asked me what I thought of the Everpix story. If you do not know it, you should read the following links:

– A very good article from the Verge: Out of the picture: why the world’s best photo startup is going out of business. Everpix was great. This is how it died.

– A very detailed account of the Everpix story by its founders on Gifthub with tons of documentation and archive: Everpix-Intelligence

I knew some actors: Pierre-Olivier Latour is an EPFL alumnus whom I met during my Index years and again in 2006 when I visited Silicon Valley with the future founders of Jilion. Neil Rimer, one of the investors in Everpix was my boss before I joined EPFL.

From left to right, Zeno Crivelli, Pierre-Oliver Latour, myself and Mehdi Aminian in 2006 in Silicon Valley.

The story will certainly feed the recurring debate about taking VC money or not, and I think it is a bias debate! You can read my recent posts about Founders Dilemmas, which address the issue:

– The Founder’s Dilemmas – The Answer is “It depends!”

– Swiss Founder’s Dilemmas

Again taking VC mmoney is not an easy thing. It is tough to get and when you have it, the constraints increase. You can watch the video Venture Capital Is a Time Bomb from the founder of 37signals if you do not know what I am talking about.

I think the debate is biased because it is not about VC vs. no VC. Not many entrepreneurs have the choice of not taking investor money (Business angels are not that different from VCs.) It is about do you want to have an impact and grow (then you often need investors) OR do you want to control and stay independant. And it is often OR not AND… I know many people (including entrepreneurs and investors) disagree with me. My recent experience has not changed this belief that I’ve had for 15 years.

You should read Founders at Work if not already. One of them claims: “VCs? you can’t live with them, you can’t live without them.” I think this is closer to the truth. He said exactly: “VCs are an interesting bunch; you can’t live with them, you can’t live without them. They are instrumental in your success because they give you money and a really strong endorsement. They have this mafia-like network of connections and they help you with deals and find the right executives. They are really working your case. In my experience, it rarely happens that they turn against you, because you’re a team and if the team isn’t working, the company will likely fail. Occasionally, when you’re a screw-up, they’ll have to make a tough decision and fire someone, but that’s rare in my opinion. Because they wouldn’t invest in your company if they didn’t believe in you and your team. So I’ve always had a good experience working with VCs.”

So back to Everpix. I do not really have a point of view as I did not know the details. But let me quote both actors from The verge article: “The founders acknowledge they made mistakes along the way. They spent too much time on the product and not enough time on growth and distribution. The first pitch deck they put together for investors was mediocre. They began marketing too late. They failed to effectively position themselves against giants like Apple and Google, who offer fairly robust — and mostly free — Everpix alternatives. And while the product wasn’t particularly difficult to use, it did have a learning curve and required a commitment to entrust an unknown startup with your life’s memories — a hard sell that Everpix never got around to making much easier.” “It succeeded in every possible way,” said Jason Eberle, who built the web version of Everpix, “except for the only way that matters.”

While the investors point was: “While the product was clearly superb and had a very small but very loyal following, we were not comfortable enough with the other aspects of the business to kick up our level of investment,” said Neil Rimer, adding, “Having a great product is not the only thing that ultimately makes a company successful.” There is the remaining issue of how much value creation VCs want and can all entrepreneurs address it: “You guys seem to be a spectacularly talented team and some informal reference checking confirmed that, but everyone here is hung up on the concern over being able to build a >$100M revenue subscription business in photos in this age of free photo tools.” Said a partner at another firm: “The reaction was positive for you as a team but weak in terms of whether a $B business could be built.”

The debate will no doubt continue, but it is close to what can inspire me this story. Not to forget the conclusion of Latour: “I have more respect for someone who starts a restaurant and puts their life savings into it than what I’ve done. We’re still lucky. We’re in an environment that has a pretty good safety net, in Silicon Valley.”

Following my recent post about Wasserman’s book, The Founder’s Dilemmas, let me react about recent (and less recent) events related to Swiss start-ups and founders. Do we have here the same dilemmas Americans face, that is building a company which is either control-oriented or wealth-oriented? If you do not know what I mean, read the blog or let me just add that there is this binary model of either slowly creating value with your customers and partners with not much investor money or taking the risk of fast growth with investors, in anticipation of customer demand.

The ultimate example of this in Wasserman’s book is Evan Williams who founded Blogger, Oddeo and then Twitter, with diverse strategies. Paul Graham addresses the issue often (for example in Startup = Growth or in How to Make Wealth) and for a young entrepreneur, getting a million can be very important. At the macro-economic level, there is also a debate which I honestly never really understood. I think an ecosystem is (or should be) interested in fast growing companies, and slow growth should be less of a focus, not because it would not be important, but because it has always existed and will continue to exist with or without public support… However, because there are many SMEs in Switzerland, the support to small firms seems to be important. So is the situation very different from what I know in the USA? Let me try a simple description.

Sensirion is a very succesful Swiss start-up which is a good illustration of the debate. In an article written in 2008, its co-founder, Felix Mayer wrote about “How to finance the Growth? Being somewhere in the middle between the “US American” who is shooting for the moon and the Swiss who develops his technology on the cash flow of a one man company we did not choose the classical venture capital path to finance the first growth phase of the company but were able to find a private investor. In Switzerland, if you look for private investors, you may find experienced entrepreneurs who are willing to invest into a promising business. They are also known as “business angels”. It took quite a while to get from a prototype to a product family or from 1 to 10 to 100 as described before. You need knowledgeable and patient partners to survive this phase with many ups and downs. Usually, it takes longer than you expect. Nevertheless, at the end of the day, you have to get to the point where you generate growth by your own cash flow, which Sensirion reached 6 years after its incorporation. Since then, we generate enough cash flow to finance our yearly growth of around 30%-40%. In order to manage this growth we are of course continuously looking for excellent people!”

Is Sensirion a different model? I went to the Swiss register of commerce and looked at Sensirion financing (the Canton of Zurich is offering very detailed information). It was not an easy exercice and I am not sure about the accuracy (You will see the figures differ slightly!). I tried also to show the dilution of founders over time:

and here is Sensirion employee growth since its inception

Sensirion is clearly a success story, but is it that different from the US model? There might be no VC, but the private investor(s) have put a total of CHF13M with a valuation of CHF190M at the last round. The growth was as fast as many VC-backed start-ups, so I am not sure the investors were more patient and the exit might be less of a priority. This is very similar to many US start-ups… But Sensirion is often mentioned as an example that start-ups would not need venture capital (hence investors). There is not that much difference between a private investor and a VC (or is there?)

Now it is true that many of the Top 100 Swiss Start-ups raise very little money with business angels In the order of CHF1-2M. Recently EPFL’s Jilion has been acquired by Dailymotion for an undisclosed amount and the local press mentions Jilion had raised about one million. Optotune in Zurich is a similar model with 200’000 raised according to the register of commerce. Techcrunch was concerned recently about BugBuster (small) CHF1M A round. Dacuda raised about one million too at a CHF7M valuation. LiberoVision raised CHF200k with Swisscom at a CHF2.5M value before being bought for about CHF8M (it might have been more with upsides). Netbreeze was acquired by Microsoft after raising about CHF5M from one group of investors which owned 80% of the company. Wuala was acquired by LaCie 2 years after its creation and it was totally self-funded. And the list is nearly endless.

But there are also fast growing companies. Covagen, GlyxoVaxyn, GetYourGuide, InSphero, Molecular Partners, Nexthink, TypeSafe, UrTurn have raised a lot of money with VCs. And people who would say Switerland is about health related firms will see it is more diverse…

| Company | Field | Money raised | Latest valuation | Investors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covagen | Biotech | 56M | NA | Gimv, Ventech, Rotschild |

| GetYourGuide | Internet | 16M | 50M | Highland |

| GlycoVaxyn | Biotech | 50M | 37M | Sofinnova, Index, Rotschild |

| InSphero | Biotech | 4M | 16M | Redalpine, ZKB |

| Molecular Partners | Biotech | 56M | 115M | Index, BB Biotech |

| Nexthink | Software | 15M | NA | VI, Auriga |

| Sensirion | Electronics | 13M | 190M | Undisclosed |

| TypeSafe | Software | 16M | NA | Greylock |

| UrTurn | Internet | 12M | 36M | Balderton |

And of course, the founders have been diluted. I will not specifically show the dilution in each company but anonymously illustrate this with the data I could found online (non confidential data).

| Company | Founders | Seed | A | B & Later | ESOP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9% | 26% | 65% | ||

| 2 | 30% | 33% | 31% | 6% | |

| 3 | 34% | 32% | 33% | ||

| 4 | 40% | 7% | 12% | 41% | |

| 5 | 43% | 47% | 10% | ||

| 6 | 35% | 11% | 27% | 28% |

I am not sure, with all this data, that Switzerland is qualitatively that different… I will finish with an interview of Daniel Borel, the co-founder of Logitech: “The only answer that I may provide is the cultural difference between the USA and Switzerland. When we founded Logitech, as Swiss entrepreneurs, we had to enter very soon the international scene. The technology was Swiss but the USA, and later the world, defined our market, whereas production quickly moved to Asia. I would not like to look too affirmative because many things change and many good things are done in Switzerland. But I feel that in the USA, people are more opened. When you receive funds from venture capitalists, you automatically accept an external shareholder who will help you in managing your company and who may even fire you. In Switzerland is not very well accepted. One prefers a small pie that is fully controled to a big pie that one only controls at 10%, and this may be a limiting factor”

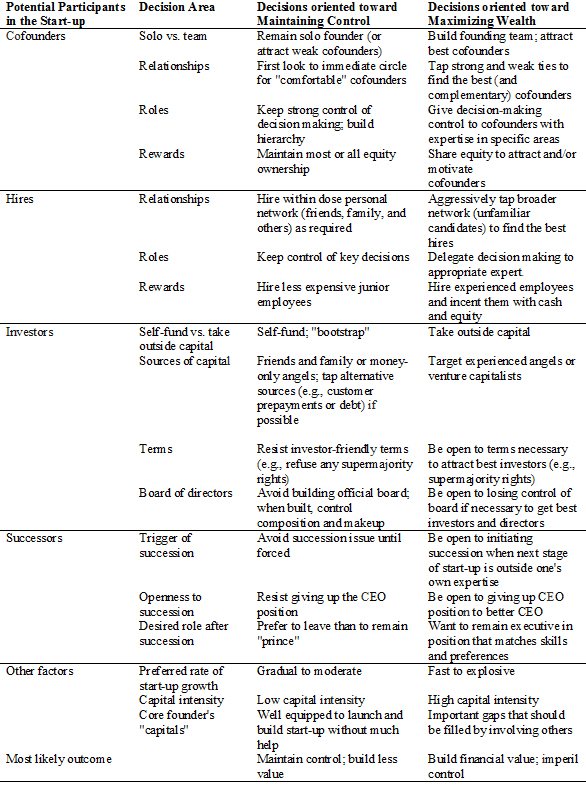

The Founder’s Dilemmas is at the same time a fascinating and frustrating book. Fascinating because it’s providing very seldom seen (and mostly unknown) data about founders and high-tech start-ups. Frustrating because it is also seldom providing answers to the dilemmas founders may face. It took me the full reading of the book to finally understand that the answer Wasserman provides is that there is no best solution for a founder facing a problem, but that if he knows all possible situations, he might better decide based on his own motivation and … personality. So she or he might decide, not on rational criteria but more because of his personal inclinations!

The best illustration of this is Evan Williams who was a founder of Blogger, and then of Odeo (and then after the book was designed of Twitter). Williams had a very different behavior with the two start-ups. He was “control-oriented” with Blogger, hiring people in his close network, taking friends and family (and close network) money only and keeping management control to the point of firing everyone including his former co-founder and girlfriend. With Odeo, he had initially a “wealth-oriented” attitude, taking VC money and having a different hiring strategy. His inclination made him however buy back his investor’s stake, as he needed to control his start-up again.

Wasserman shows that the “3Rs” (Relationships, Roles & Rewards) are key features for decisions about the key dilemmas founders may experience. These dilemmas are classified according to the chapters of the book: Career, Solo-vs.-Team, Weak vs. Network, Positions, Compensations, Hiring, Investors, and Succession. Wasserman explains (or better-said describes) the various dilemmas founders face when taking decisions and shows that their decisions are very often dependent upon their motivation. Do they want to be Kings (power or control-oriented) or Rich (wealth oriented)? He does it with anecdotes (not so good and quite well-known) and with statistics (very good and not so well-known)

In summary I saw it more as a book for academics than for entrepreneurs and founders who apparently will not take better decisions after reading this book as they will be driven by their motivations, not their experience! At least they will be aware of it. It may be another illustration that youth and enthusiasm are as important as experience and rational behaviors!

One interesting puzzle Wasserman addresses is why individuals decide to become entrepreneurs, often thinking that they will become wealthy whereas this is entirely wrong. This has to do with control vs. wealth. You will need to read Wasserman if you want to know more.

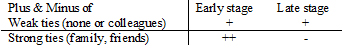

Here are some more notes taken when reading. The next table is probably an essential part of the control-vs.-wealth dilemma.

Table 1.2 (& 11.1) – Wealth-versus-Control Dilemmas

Wasserman has many more interesting data and let me show a small sample:

– There are no real pattern in becoming a founder (age, experience, childhood influences, personality, family status, economic status), however early influences and natural motivations seem to be important.

– About age, he has seen a wide variation with an average of 14 years of work experience before becoming a founder (higher in life sciences). There is a specific group of founders with 0-4 years of experience.

– The main motivations are either control or wealth, but having an impact counts.

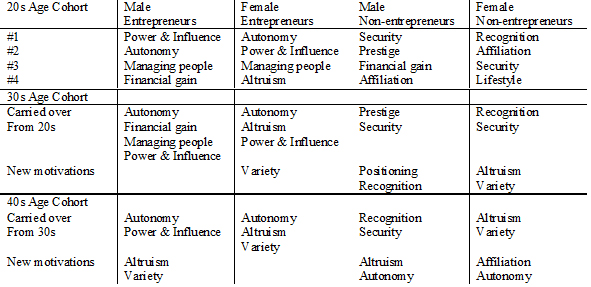

– Wasserman shows strong differences related to gender correlated with age. This is a must read but too long to be explained here…or are they, let me try [pages 33-35]

Tables 2 – Motivations of male and female entrepreneurs

– Ethnic homogeneity occurred 46 times more often than not (and still 27 times more often to control for family ties). And it diminishes conflicts risks, they are therefore more stable.

Size of founders’ teams

Founding with friends…

– 40% of teams had prior professional relationships and 17% family ties.

– Each such relationship added a 30% likelihood of founder departure.

– As a summary

“A friendship built on business can be glorious, while a business built on friendship can be murder.” [Page 104]

Jobs and Wozniak is a good example: they did not clarify crucial issues and “he got paid one amount, he told me he got paid another. He wasn’t honest with me, and I was hurt… But you know… he was my best friend, and I feel extremely linked to him.” They eventually parted ways. [page 109]

About decision making: “Two people at the wheel is the worst way to drive. You end up going straight when either a right or a left would be better.” A reason why being three might be good.

Woman compensation

There is a much greater gap in the preponderance of women than in their compensation. Only 10% were C- or VP-level (17% in life sciences) and 3% and 7% were respectively CEO. But the compensation was 5% below.

On BAs vs. VCs, Wasserman shows the usual dilemmas. Dick Costolo about too many BAs: “It was a recipe for disaster. I had 13 people who, now that they had $20’000 invested, wanted to call me and ask about […], taking 45 minutes of the CEO’s time when he should be running the business.”

Succession of CEO

Conclusion

Wasserman strangely mentions here: “What is entrepreneurship? A widely used definition is a process by which individuals pursue opportunities without regard to the resources they currently control”. It sound even romantic, but it has a dark side: founders are 60 times more likely to be resource-constrained than have all the resources they need. Lack of resources lies behind all the dilemmas described. [Page 333]

Founders who had kept control held equity stakes which were [half] as valuable as those held by founders who had given up both CEO position and board control.

There are hybrid paths, compromises between control and wealth, using “second-tier” solutions (hiring, investors) but Wasserman shows it is even riskier. Consistent decisions give a higher likeliness of desired output (either control or wealth).

So the answer to dilemmas is “it depends.” Be knowledgeable about options and consistent in your choices!

Wasserman opens new directions for research:

– Who are these special animals which obtain both control and wealth (Gates, Ellison, Jobs 2.0…)

– Serial entrepreneurs: they receive larger equity stakes, remain CEOs longer, negotiate better investment terms and might be more successful. Are they?!! (cf Serial entrepreneurs: are they better?)

– How often is a control-oriented founder able to sell a start-up for which he owns 100%, for $5M and how often is a wealthe-oriented founder able to sell for $100M a company of which he owns 5%…

– Wasserman is aware all this is specific to high-tech and the USA. What about outside these boundaries?

“Any honest model of a complex human phenomenon has to acknowledge many unknowns”

I plan to come back on the Founder’s Dilemmans with a look at recent Swiss start-ups situation…