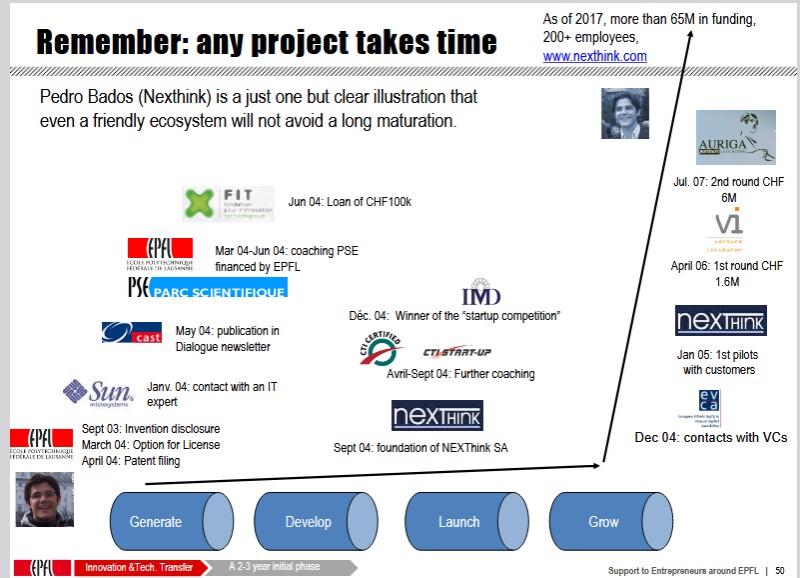

This doesn’t happen that often in a lifetime [1], so it deserves a pause: Nexthink, a spin-off from EPFL, has just been acquired for $3 billion [2] — you read that right, $3 billion!! Admittedly, Nexthink isn’t exactly young anymore; it was co-founded in September 2004, by Pedro Bados, who came (I believe, to do a master’s internship as part of the Erasmus program) in the artificial intelligence lab. AI wasn’t what it is today. His project was based on Bayesian methods… As luck would have it, I met Pedro then to analyze the intellectual property he had generated and what could be done with it. Pedro wanted to sell the patent that EPFL had filed, and when he discovered it wasn’t generating as much interest as he had imagined, I suggested, “Why not a startup?” That became my main role. I also helped him structure the initial deal, I mean who he would work with, within EPFL and outside, and made some introductions at the time. The rest is history !

Pedro has become a discreet but essential figure in the Swiss ecosystem [3]. He was our guest for ventureideas as early as 2006, along with Jordi Montserrat.

Here are notes taken at the time from his présentation (pdf).

NEXThink notes

He also gave a beautiful interview ten years ago to the newspaper Le Temps (in French): Nobody is ready to be an entrepreneur

I’ve had some wonderful experiences in my professional life, in scientific research first between Paris and Stanford University, then in venture capital with Index Ventures, finally at EPFL for 15 years, and for the last 6 years at Inria. Nexthink will certainly remain one of the best ones, and I hope to experience a few more. As I said 15 years ago [4], my professional passion is to encourage these kinds of ventures (see the Stanford interview): “A love of entrepreneurship, a passion that I took back home to Europe after studying here [at Stanford University]. I want to see a stronger entrepreneurial culture there, and I am working in more than one way to effect that change.”

A few notes:

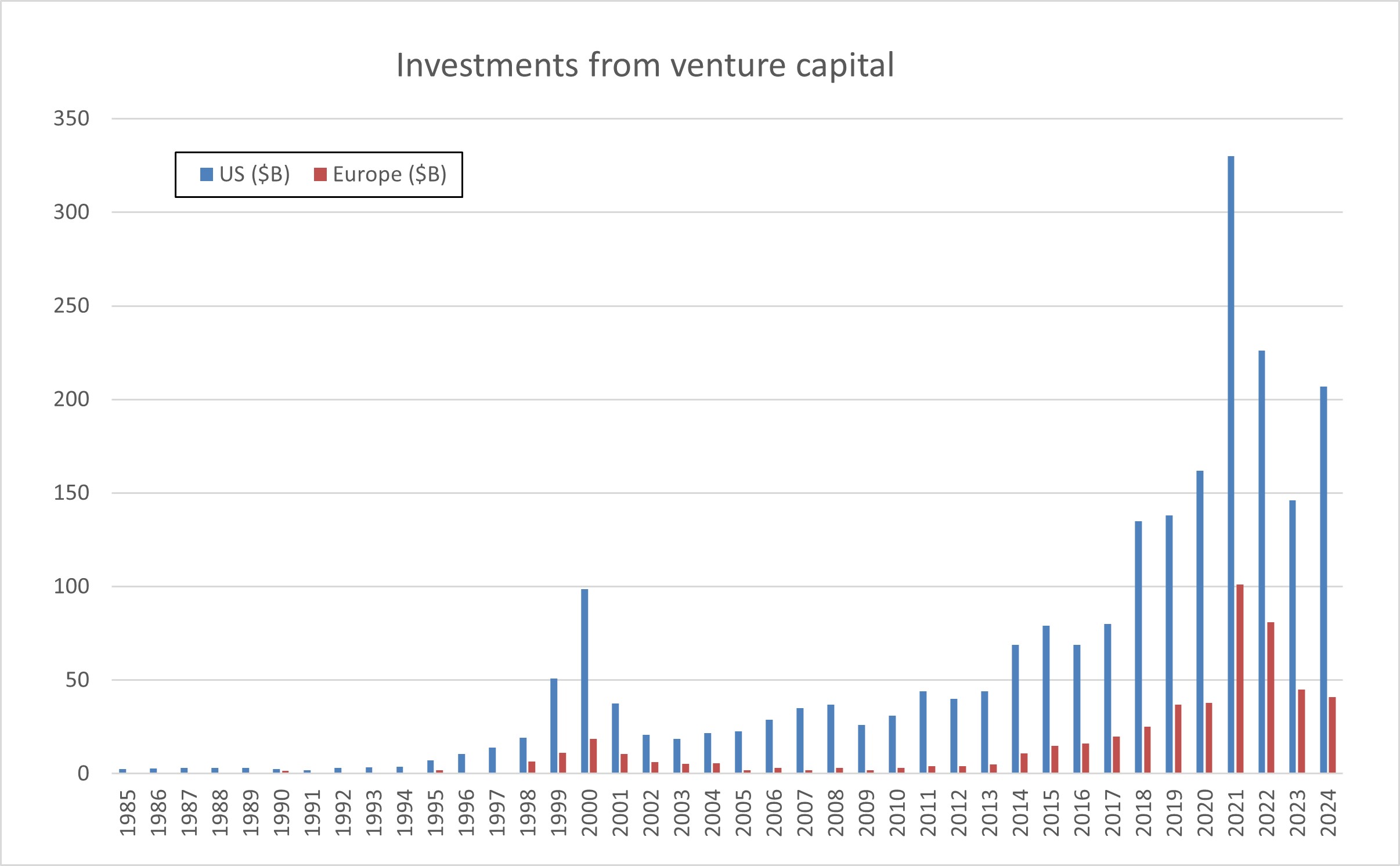

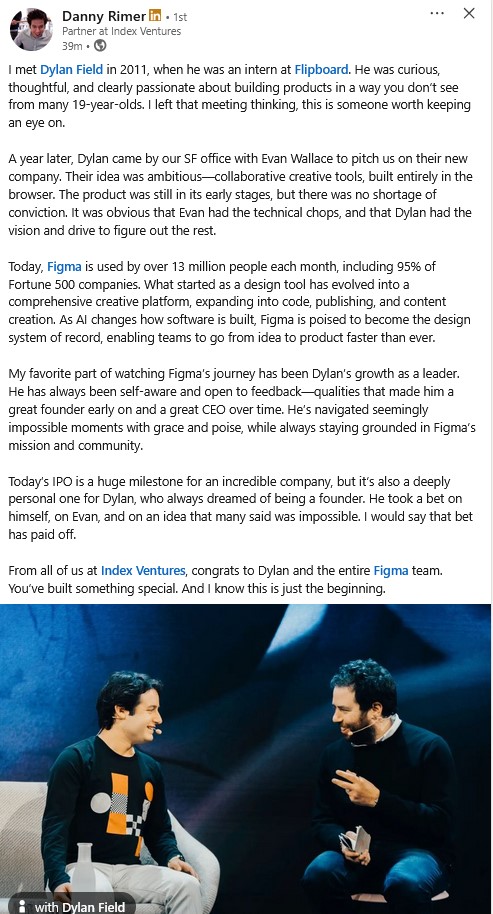

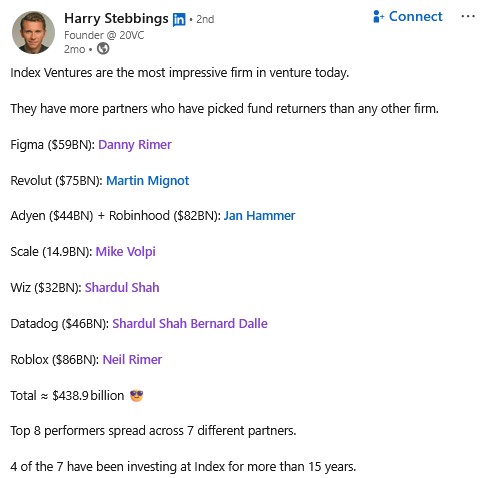

[1] I was struck some time ago by this post about Index Ventures and its stratospheric performance :

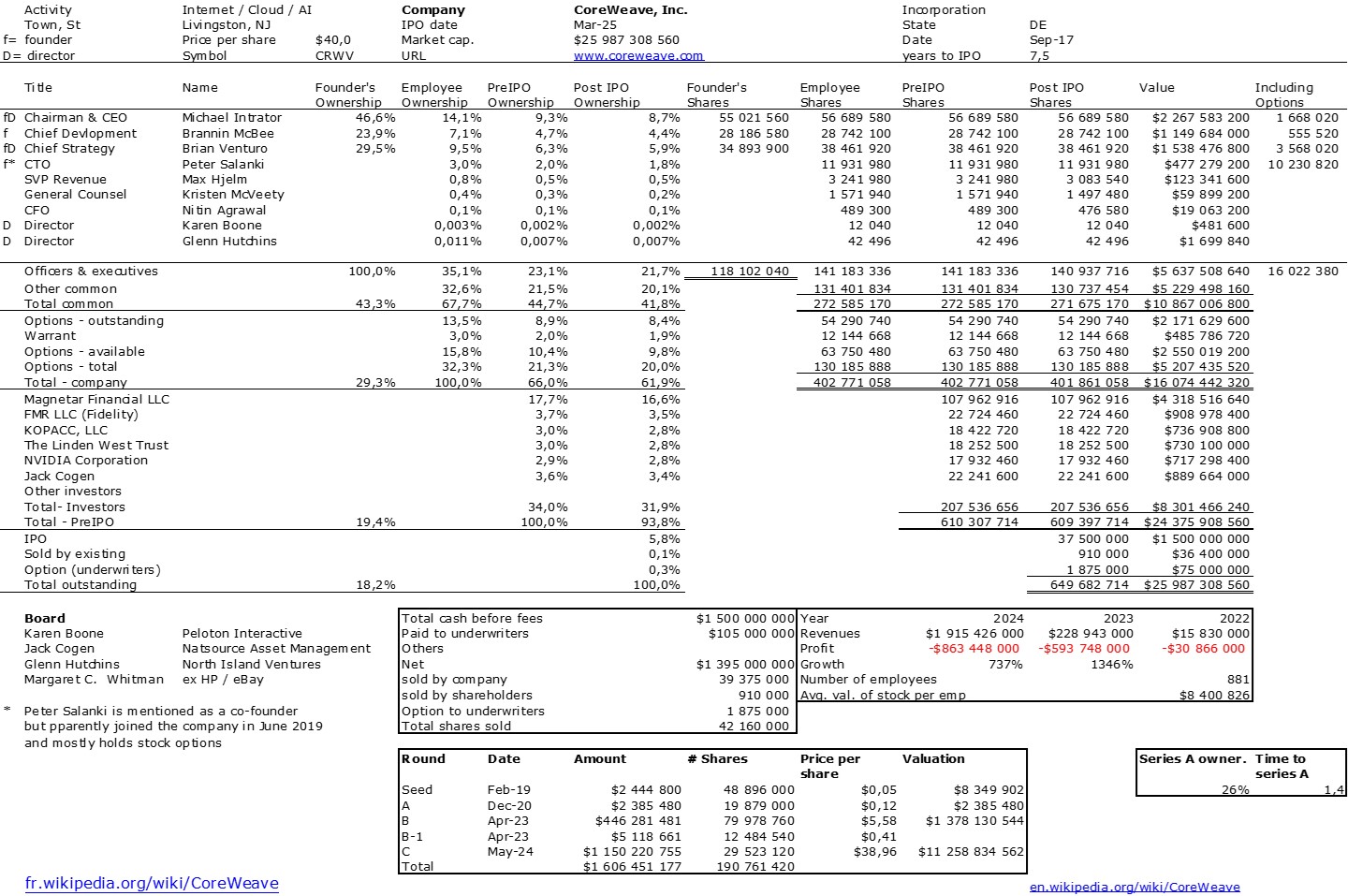

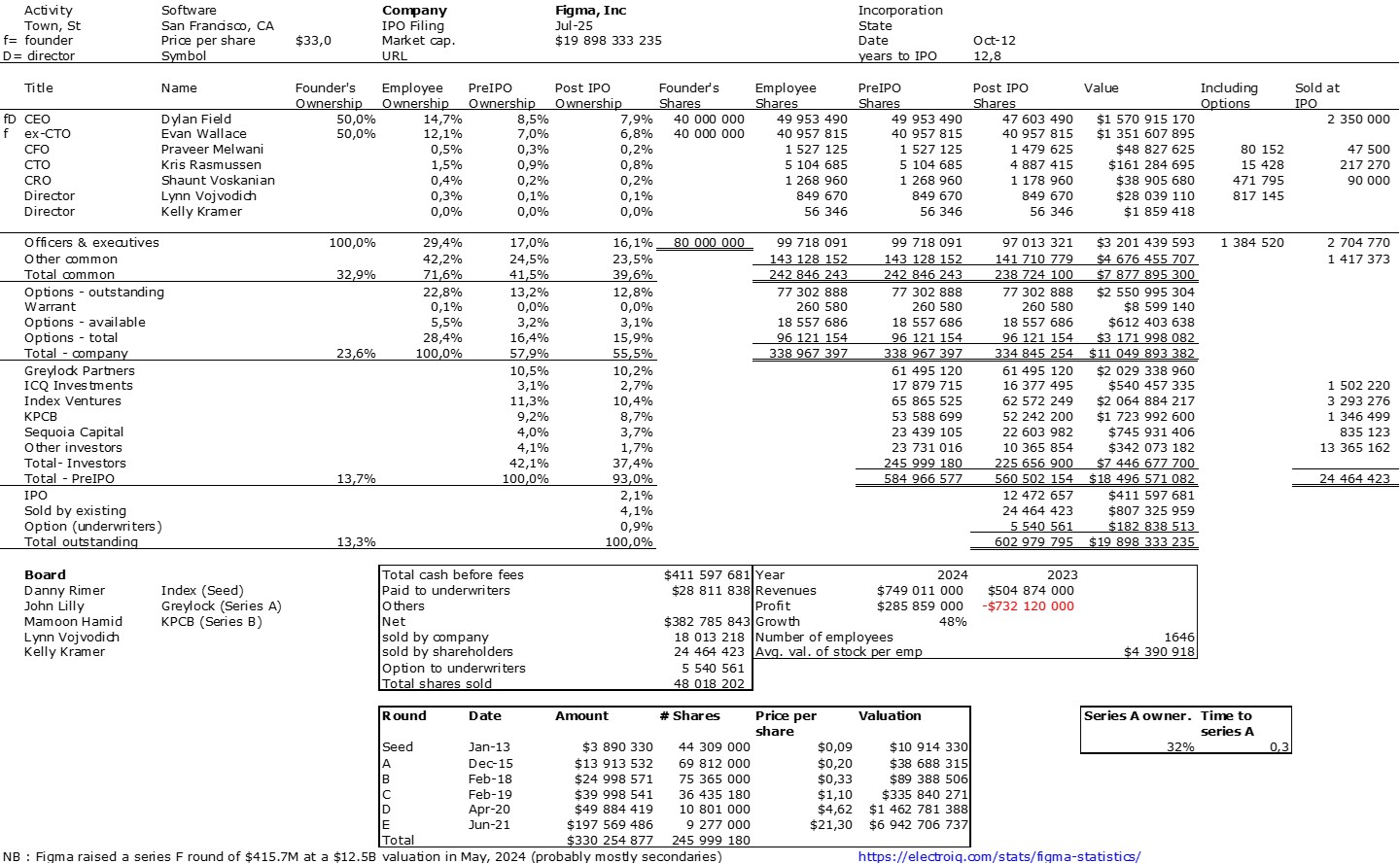

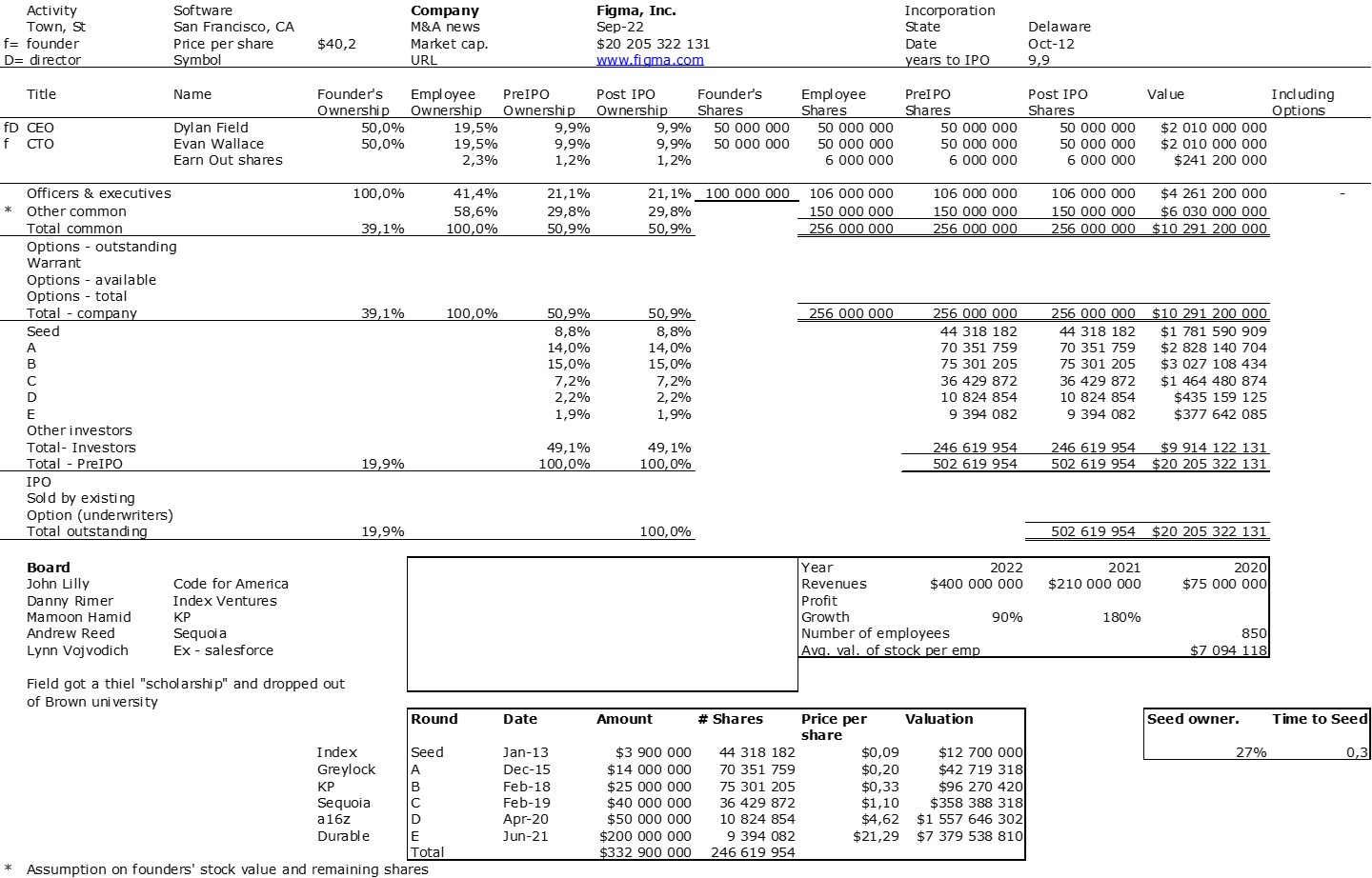

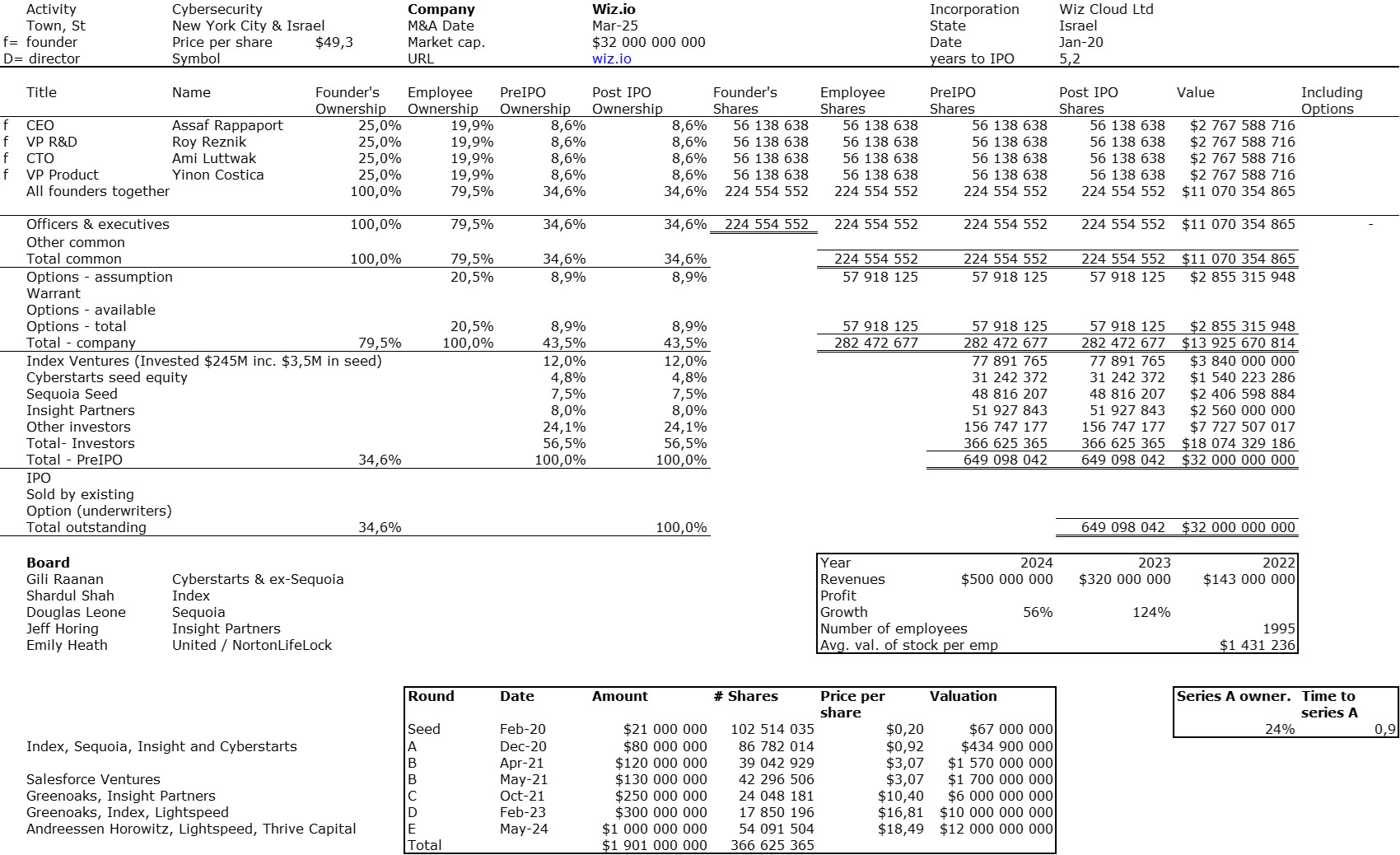

8 startup with an exit above $10B : Figma – $59B, Revolut – $75B, Adyen – $44B, Robinhood – $82B, Scale – $14.9B, Wiz – $32B, Datadog – $46B, Roblox – $86B. So what does $3B represent for Index? And I don’t have a list of their exits above a billion. I remember Virata, Numerical Technologies, The Fantastic Corporation, and Skype before 2005. I might ask them!

[2] Some more news and archives – What I found online about Nexthink acquisition, mostly LinkedIn posts by its founders and investors as well as press articles

Nexthink News autour acquisition

Neil Rimer (Index ventures) and Pedro Bados I am not sure where and when

[3] A short presentation of the EPFL ecosystem to its alumni before 2010 that mentions Nexthink (pdf)

a3angels10-herve_lebert-innogrants[4] Thanks to my favorite search engine, an exchange about what I thought of startups, Silicon Valley in 2008 where I mention Nexthink. I am not sure things have changed that much…

Stanford HL