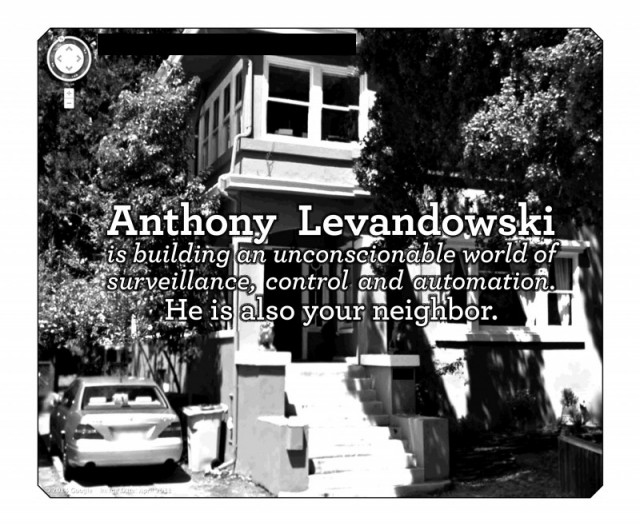

This is a short text I wrote in 2012, and my friend Will from Finland had made comments about it which I added. Thanks! I read it again this morning and thought it might be worth publishing it now…

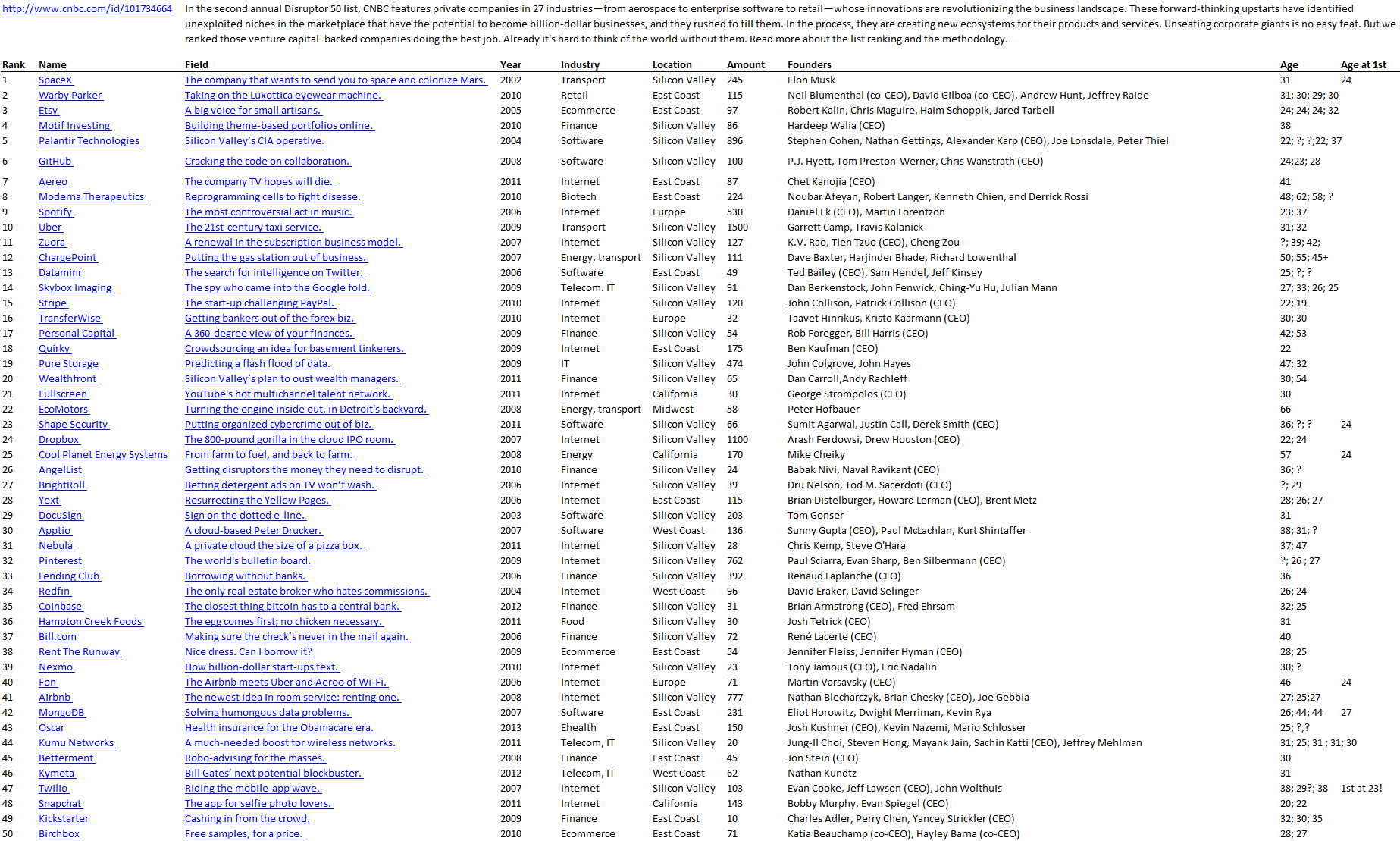

Intel, Apple, Microsoft, Oracle, Genentech, Cisco, Google, Facebook, Skype. You probably know these companies. They were at the origin of major innovations for our societies. Maybe you are less aware of Niklas Zennström and Janus Friis, Mark Zuckerberg and Dustin Moskovitz, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, Leonard Bosack and Sandy Lerner, Bob Swanson and Herb Boyer, or Larry Ellison but you know much better Bill Gates and Paul Allen, Steve Jobs and Stephen Wozniak, Bob Noyce and Gordon Moore. They are entrepreneurs; the founders of companies that were all start-ups one day in the not-so-distant past, but are global titans today. Europe does not seem to understand the importance of high-tech innovation produced by these young entrepreneurs. Skype is the exception in the list and the Americans were able to produce hundreds of such success stories. Why have we failed and what can we do to change the course of history?

Innovation is a culture where trial-and-error and uncertainty have huge roles. Failure, unfortunately or maybe fortunately. Just as life! The European culture in all its diversity has provided welfare to its citizens since the end of World War II. Ironically, the comfort-level we all appreciate will actually accelerate its end. A culture can only live with creativity and renewal. As a recent article in The Economist illustrated it well [1], we Europeans are no longer able to innovate, our businesses are too old, at least in technological innovation (e.g. Nokia or Alcatel) and we do not create enough innovations. The causes are probably numerous, but fear of trying is the most serious. And I’m not sure that we are aware of it. Do many Europeans understand that innovation through high-tech entrepreneurship is critical? I fear that we would rather have well-educated children to enter the large established firms than creative individuals willing to try their luck. Worse, what models do we have?

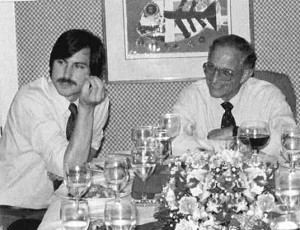

Bob Noyce was a model and a mentor for Steve Jobs.

In this unique place, Silicon Valley, thousands of entrepreneurs try each year. “The difference is in psychology: everybody in Silicon Valley knows somebody that is doing very well in high-tech small companies, start-ups; so they say to themselves “I am smarter than Joe. If he could make millions, I can make a billion”. So they do and they think they will succeed and by thinking they can succeed, they have a good shot at succeeding. That psychology does not exist so much elsewhere” wrote Tom Perkins, co-founder of the legendary Kleiner Perkins fund.

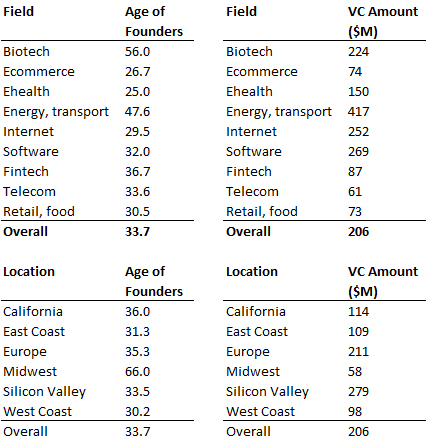

Europe is not fully unconscious of the problem. In 2000, the Lisbon agenda proposed by theEuropean Union had the ambition to make of Europe in 2010 “the most competitive knowledge-based economy”. This has been a total failure. A variety of support mechanisms were created, but the Europeans seem to have forgotten that innovation is primarily a question of adventurers, pioneers – these types of people by definition are not looking for safety and support. Entrepreneurs live on their passion. “Launching a start-up is not a rational act. Success only comes from those who are foolish enough to think unreasonably. Entrepreneurs need to stretch themselves beyond convention and constraint to reach something extraordinary” says Vinod Khosla, another Silicon Valley icon. A start-up is a baby whose founders are its parents. Not surprisingly, founders often start the adventure as a couple, because they have the intuition it will be difficult and they need more than one mind and body. They are often migrants. Probably because migrants do not have any existing network or “right” connections in the new places where they have settled, they simply work passionately on their innovation, again raising the probability of success. Half of the entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley are not Americans. Why are we afraid of that opportunity in Europe? Silicon Valley is an open culture where even competitors like Apple, Google or Facebook talk and cooperate. This is REAL open innovation, not high-level top down roadmaps, but grassroots, bottom up collaboration. Interestingly, entrepreneurs are often young. While this is not always the case, youth does not give up on creativity easily, largely because they have not lived through the many failures that the rest of us have. Silicon Valley is a unique place in the United States that no one could replicate. And yet every state, every region of Europe is desperately trying to create its own! Let’s work together. By no longer seeking to create the Holy Grail, one unified “European technology cluster”, and by instead deciding to cooperate on a practical level to enable innovators rather than trying to do the work for them. While our egos are still too large to give up our dreams of global domination, at least let us work together without unnecessary waste! In a recent talk [2], Risto Siilasmaa, the young chairman of Nokia, called for a similar reaction and added that “entrepreneurship is a state of mind, which implies pragmatism, ambition, dreams, perseverance, optimism and give-up-&-start-again attitude”. Without a large ambition, it is not worth trying.

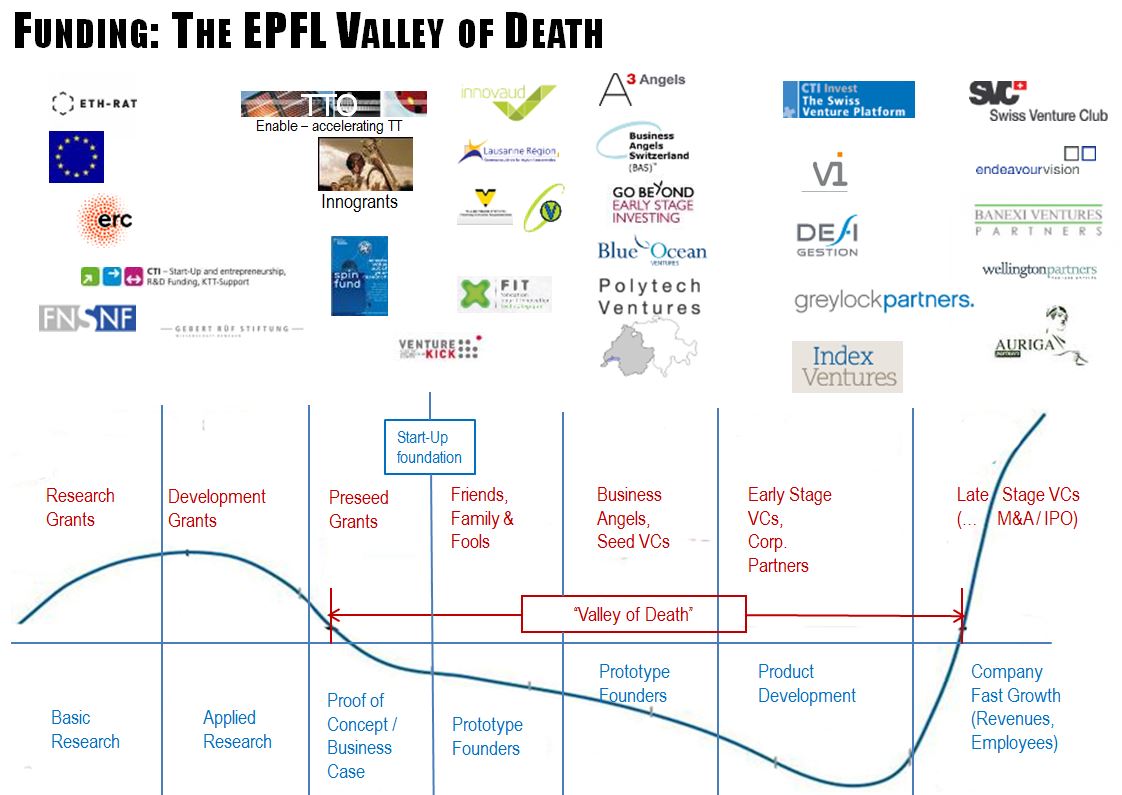

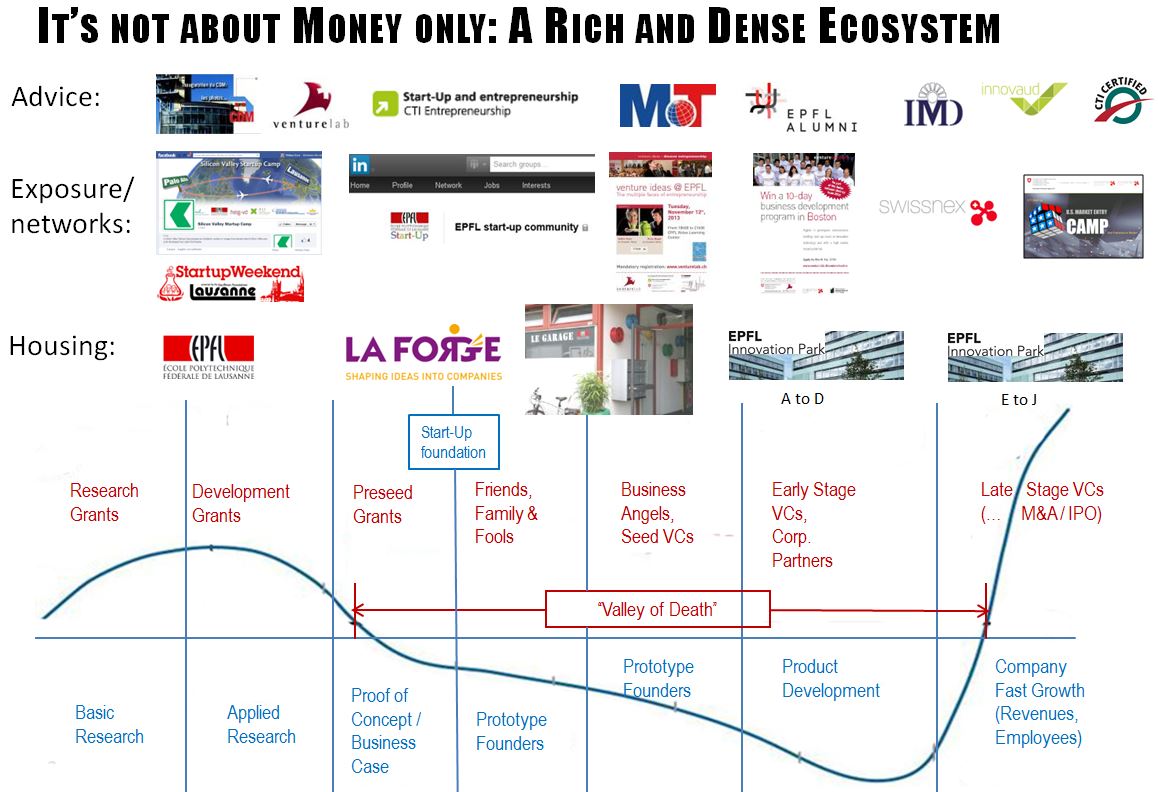

One concrete area to focus on is creating an infrastructure where risk-taking investors can thrive. Entrepreneurs cannot succeed alone. Very early in the innovation process they need investors to enable them to embark on the adventure. America has created the best tool out there so far, venture capital: former entrepreneurs who become the supporters of the next generation once they have already succeeded, financiers who have “been there and done that” [3]. These VCs know the start-up culture because they have been there! This experience complements the expertise provided by others who have spent years in large corporations; a perfect storm of competence and culture is needed. It also requires employees who also digested this culture, employees who can take a stake of the future success of the company through stock options. I said stock option, the word that became a bad word, the tool to fatten those who do not deserve it. Stock options should go to those who try. No doubt it will also require some labor flexibility for start-ups as they face uncertainty and rapid cycles. But it should not be assumed that the absence of these mechanisms is the cause of our failures. It is the absence of this culture of innovation that hurts us. Do not be afraid of failure. Failure is the mother of success, says the Chinese saying. Does the child successfully ride the bicycle on her first attempt?

Failure will always be part of innovation. This is why we need a critical mass. In one single place or not, in Europe. And failure should not be stigmatized. I think everyone interested in innovation needs to experience the Silicon Valley culture, to spend time to understand. Weeks or even months. Without fearing that our children will not come back. It is better to try out there than be safe back here. They will return to teach us, at worst, and at best return to set up Europe’s future growth companies! We also need to support high energy mobility among entrepreneurs across European hotspots, as we have done very well for our students. Universities are still critical once the students have left to provide landing zones for mobile entrepreneurs. You may criticize me for being too fascinated by the American culture and technological innovation. “Europe has other ways to innovate,” I am often told. It innovates with large corporations such as Airbus or with German- or Swiss-like SMEs, or in services. And you believe that US companies do not?! I am told that venture capital is in crisis, that Silicon Valley innovates less, and that may well be true – outside of the web, creativity seems to slow down. Schumpeter, the great economist, has built a theory where large established firms die and are replaced by new entrants when they do not innovate anymore. Why would the twenty-first century be different from the previous one? Maybe … but our energy, aging, health problems are not going to require new innovations and new entrepreneurs? I do think so. Europe needs a new ambition, a new enthusiasm and we Europeans are aging. We owe this to our children, to our youth. From primary school onwards, let us our children express their creativity, let us teach them to say no, and tell them that this is positive. A career is meaningless unless it includes passion and ambition. Let us not encourage them to follow the paths of certainty that may be deadly. Steve Jobs in a wonderful speech in 2005 [4], indicated that we were all going to die one day, and before that day, we needed to stay hungry, to day foolish. Let us follow his advice. Let us help our children!

Hervé Lebret supports high-tech entrepreneurship at EPFL. He is the author of the blog Start-Up, www.startup-book.com.

[1] Les Misérables – Europe not only has a euro crisis, it also has a growth crisis. That is because of its chronic failure to encourage ambitious entrepreneurs. The Economist, July 2012. www.economist.com/node/21559618.

[2] Risto Siilasmaa at the REE conference. Helsinki, Sept. 7, 2012.

[3] Do not miss the movie SomethingVentured which describes wonderfully and humorously the early days do venture capital, www.somethingventuredthemovie.com.

[4] Stay Hungry, Stay Foolish. ‘You’ve got to find what you love.’ http://news.stanford.edu/news/2005/june15/jobs-061505.html.

Again a few key points:

• Europe is behind USA and Asia in innovation.

• Entrepreneurs are not considered heroes in Europe.

• Trial and error, uncertainty, and failure are integral parts of innovation

• Our high level of comfort will accelerate its own end (again creative destruction).

• Fear of trying is the most serious problem with innovation.

• Europe’s 2000 mandate to become the world’s leading knowledge based economy has failed.

• Open Innovation is bottom up, not top down.

• Youth are creative because they have yet to experience failure.

• We must create an infrastructure where risk-taking investors can thrive.

• All students that show interest and ability in innovation should experience the Silicon Valley Culture. We should not worry that they will no come back.

• Europe’s leading universities can be the game changers, the catalysts, by agreeing on what is important (what innovation, what education, what tech. transfer) and investing in it.