A year ago I had published a post about the tech giants, entitled Nothing changes but their names ! Here is just a short update one year later.

Category Archives: Silicon Valley and Europe

The World of Startups according to Marion Flécher (Part 2)

In my post of November 8th, I promised to “read Marion Flécher’s book with great interest and will write to you in a future post to see if I find cause for resignation or optimism regarding the startup world.” I’m going to say both! The book is indeed excellent and perfectly describes the differences between France (which tried to claim to be a Startup Nation) and Silicon Valley (which never felt the need for such a claim).

The Difficulty of Defining the Word “Startup”

The heart of the book is not the comparison between the two regions, but rather what the French startup scene is like; I will return to this point. In her introduction, she explains the difficulty in defining the word, to the point of writing: “Making startups my subject of study was not a given. […] I was encouraged to use alternative terms such as innovative companies, technology companies, or high-growth companies” [page 16]. With a striking analogy, she adds, “as with the art world, in which players spend their time trying to determine what is art and what is not, it is by observing how a world makes these distinctions, and not by trying to make them ourselves, that we begin to understand what is happening in that world” [page 20]. Without naming Steve Blank, through a survey of entrepreneurs who gave her a multitude of definitions, she almost mentions my favorite definition: “a temporary organization in search of a repeatable and scalable business model”.

Silicon Valley, Heart of Startups

In her first chapter, Marion Flécher describes Silicon Valley, the region that gave rise to the semiconductor, the microprocessor, the microcomputer, software, the internet, social networks (and ultimately artificial intelligence, which had not yet emerged when she conducted her research). She demonstrates that the region was at the heart of a revolution that goes beyond technological innovation. This innovation was “accompanied by organizational and managerial innovations that led to a profound ideological redefinition of the entreprise” [page 52].

Yet, she shows that pinpointing the moment of their emergence is just as difficult as defining startups. “For many historians and ethnologists specializing in Silicon Valley, it is Intel’s invention of the microprocessor that constitutes the true starting point of the region’s technological boom and rise to power” [page 39]. She does not, however, neglect to note the importance of Hewlett-Packard (founded in 1939) and Fairchild (founded in 1957) in this dual revolution, including the development of project-based work in small teams, the upheaval of dress codes, and the implementation of new incentive structures [pages 52-53]. The complexity of the region’s origins also stems from the existence of other significant influences such as free software and the “Do It Yourself” culture [pages 55-56], and from a diversity of major players including venture capital funds, the federal government, and the companies themselves. A world, as the author describes it, an ecosystem.

Another difficulty addressed by Marion Flécher, at least for a Silicon Valley enthusiast like myself, is: when did the word “startup” first appear? “The term ‘startup’ seems to have been used for the first time in 1976, in a Forbes magazine article, to refer to young technology companies in Silicon Valley” [Author’s note: The Unfashionable Business of Investing in Startups in the Electronic Data Processing Field]. “The term ‘startup company’, which associates the startup with a specific type of business, appeared a year later in an article entitled ‘An Incubator for Startup Companies, Especially in the Fast-growth, High Technology Fields,’ published in Business Week in 1977.” The author adds that the term acquired its current meaning and spread worldwide during the 1990s, even though this new business model can be traced back to the 1940s. NB: I confirm this in a blog post: When was the word “start-up” first used?

![]()

Scan of Figure 2 [page 43]: Timeline of the main Silicon Valley technology companies. I circled two things by hand while reading. My surprise at seeing only one founder for eBay; I thought Jeff Skoll was a co-founder, but apparently he may have only been the first employee. And my other surprise at seeing three co-founders for Apple, which is rarely mentioned. Ronald Wayne is often forgotten. And then a rather unimportant note for Marion Flécher: Wo[lk]zniak is misspelled on page 41!

Risk and Uncertainty

In a brief but equally excellent section on venture capital, Marion Flécher explains that “unlike risk, which refers to a situation that can be predicted by probability and in which actors can reason rationally […] uncertainty refers to a situation in which the degree of singularity is such that it cannot be compared to any other. By developing disruptive innovations, Silicon Valley entrepreneurs create situations of radical uncertainty in which actors can only make speculative judgments” [page 46]. This explains why the term [ad]venture capital is very different from the term capital-risque in France (which is undoubtedly indicative of dissimilar worlds). “Nevertheless, these players have resources that allow them to transform the uncertainty of a situation into a quantifiable risk. Their activity requires, first and foremost, a sound knowledge of the technical environment, which enables them to assess the growth prospects of projects. Most investors […] are thus often former engineers or entrepreneurs” [page 47]. This is undoubtedly another major difference between Silicon Valley and France.

Since I mentioned personal surprises in the commentary on the figure above, I take this opportunity to add a few more personal comments (for myself, the author, and any potential reader!):

– Without a doubt, the startup world is a new illustration of capitalism, and this has undoubtedly been misunderstood. Startups have never been liberated companies; trade unions are very rare, not to say unwelcome. I already mentioned this point in my first post.

– Marion Flécher emphasizes intellectual property (Microsoft’s proprietary software, Intel’s microprocessor patent), which creates near-monopolies favored by a state that “seems to have implicitly supported market concentration” [page 49]. Yet it was the state that forced Bell Labs to grant licenses for the transistor, for which the company held the patent. Intel certainly had a near-monopoly on the microprocessor, even though IBM and AMD were genuine competitors. But competition in new sectors has made Intel a declining player in recent years (telecommunications, artificial intelligence). I would say that the US government is protecting the country at a macroeconomic level by defending its technological lead rather than protecting any individual company. OpenAI might replace Google, which could have replaced Microsoft, just as Nvidia or even AMD might replace Intel. The same goes for mobile phones. The US remains the leader.

– Another minor point of doubt: “Between 1998 and 1999, venture capital almost doubled, going from $3.2 billion to $6.1 billion” [page 48]. I have the impression, and I could be wrong, that the amounts were about ten times larger and that these figures correspond more closely to the 1980s.

– Finally, I see confirmation of a personal impression regarding the decrease in the number of IPOs: Silicon Valley had 417 IPOs in 2000 compared to only 14 in 2021 [page 51]. Indeed, for years I’ve been compiling market capitalization tables and dreamed of quickly reaching 1,000, but the IPO drought is slowing my ambition… On the other hand, M&A acquisitions still seem as prosperous as ever, since Marion Flécher mentions more than 90 acquisitions by Facebook since its creation (see my posts on Cisco and Google). A startup may not be destined to become a long-term business, but it’s also possible that the monopolistic concentration mentioned above is at its peak…

France, a nation of startups?

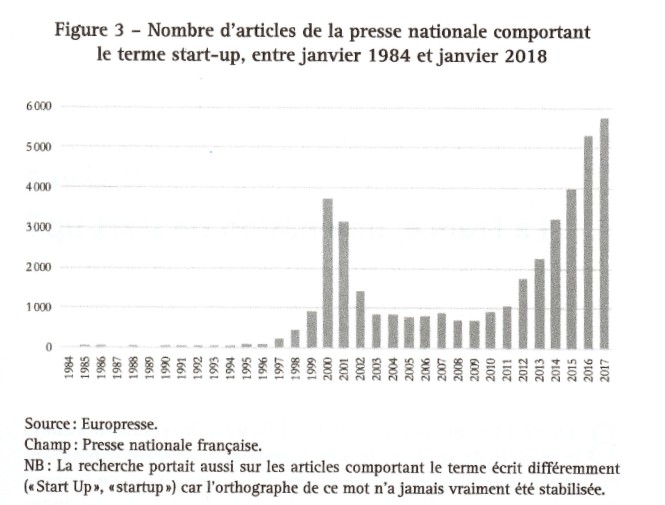

That’s the title of Chapter 2. And the second page of this chapter includes the following figure. It’s easy to see that the French press began to take an interest in the subject during the dot-com bubble and then again from 2012 onwards. Manon Flécher explains that this second period is significant, coinciding with the arrival of Uber and Airbnb in France, but also with the creation of BPIFrance and the French Tech initiative. Equally interesting, the author reminds us that General de Gaulle visited San Francisco in 1960, Georges Pompidou 10 years later, and François Mitterrand in 1984. The author doesn’t mention the creation of Sophia Antipolis in 1969, which Paul Graham mocks, more or less gently (see my post from 2011). Presidents Hollande and then Macron have been apparently much more involved in the topic.

Is France a startup nation? The answer is clear if you’ve read the preceding paragraphs. But the debate runs deeper, as I indicated in *Politics vs. Economics: A Country Is Not a Startup*, translating the article Non, la France ne doit pas devenir une start-up. I didn’t know, or had forgotten, that Emmanuel Macron had then used the term “hyper-innovation.” But the doomsayers are always ignored, and hyper-communication too often trumps reality and facts.

Marion Flécher also addresses this by stating that “despite this growth, the State remains the primary funder of startups in France” [page 71]. Her footnote on page 69 is revealing. “In 2015, business angels reportedly invested a total of €41 million, which was still half the amount in the United Kingdom and 2.5 times less than in Germany. […] In 2023, the United Kingdom continued to lead other European countries with €307.4 million invested by business angels, compared to €198.5 million for Germany and €142.5 million for France.” BPIFrance represents two billion euros in direct investments in company capital [page 72].

My post is already too long, which is convenient since I’m at this point in my reading of Le Monde des startups. Yet I haven’t even started on the main topic: the sociology of startup founders. A sequel coming soon!

Post-scriptum : On a related note, I just bought *Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World*, one review of which says, The most comprehensive — and incendiary — history of the place that we’re ever likely to get. A sweeping and unsparing critique, it’s also well written, frequently surprising and, because history tends to rhyme, increasingly urgent. You may never think about Stanford, iconic tech companies like Hewlett Packard or, indeed, the Valley itself the same way again. I won’t.” LOS ANGELES TIMES

The introduction already haunts me: the author promises to explain that the inhabitants of California, Silicon Valley and Palo Alto have not all forgotten the ghosts that surround them and without which the region could not have become what it is… To be continued!

The World of Startups by Marion Flécher

The startup world has been the core of my professional life for almost 30 years. I know it perhaps too well, and I also read almost everything I can get my hands on. So I feel compelled to read a book that takes this subject as its title. Marion Flécher is a lecturer in sociology at the University of Paris Nanterre, and her book, *The World of Startups* (Le monde des startup) is based on her doctoral thesis, entitled *The Startup World: The New Face of Capitalism? An Investigation into the Modes of Creation and Organization of Startups in France and the United States*. (Le monde des start-up, le nouveau visage du capitalisme ? Enquête sur les modes de création et d’organisation des start-up en France et aux Etats-Unis).

Marion Flécher just post an article on LinkedIn pand she was alos the guest of Guillaume Erner yesterday morning on France Culture.

As you may have guessed, I haven’t read the book yet, but I will as soon as I receive it. I’m always a bit ambivalent when I read critical analyses of this world, and of Silicon Valley in particular. Here’s what the publisher says on the book’s page: “The book compares the promises made by startups (success stories, meritocracy, flexibility) with the reality on the ground (failure rates, mass layoffs, pressure to perform, burnout). For the past fifteen years or so, young, innovative companies grouped under the term “startups” have occupied an increasingly prominent place in the media and political arena. Symbols of modernity and Capitalism 2.0, they are being held up as a genuine economic and organizational model. How can we understand this enthusiasm? (…) Dismissing the mythical figure of the self-made man, she sheds light on the reality of this social world and defines the profile of those, and more rarely those women, who launch startups and claim this label. While they claim to break with the hierarchical rigidity of traditional firms, startups offer a new face of capitalism, one whose gentler and more colorful aspects have allowed it to recover from its critics. In the digital age and the era of new technologies, what do they foreshadow for the future of work?”

I am ambivalent for two reasons :

– The first reason is that it seems to me France has gone from a profound ignorance of this world to a critique of its excesses that is undoubtedly justified but harsh.

About ten years ago, Professor Libero Zuppiroli brilliantly criticized the unfulfilled promises of innovation in *The Utopias of the 21st Century*. A few years earlier, he had teased me about the fact that startups didn’t represent much at all. That was the subject of another post.

He was right, at least for Europe, to the point that neither France nor Europe has generated any real success stories. My previous post last week celebrated an EPFL’s success story at $3 billion, and Criteo, Mistral, and others are all modest in size compared to the behemoths that the GAFAMs have become. SAP, Spotify, ARM, and only a few others in Europe can be compared to American successes. I am therefore sometimes torn between comparing and criticizing two continents that have little in common. France has moved very quickly, not to say too quickly, from a lack of understanding to a criticism of this world without grasping the reasons for its appeal and success.

– The second reason is that this criticism has existed for a long time, and I’m saddened that communication takes precedence over information. Startups have never been a paradise; they are rarely liberated companies, so storytelling has transformed a few exceptions into a universal model.

For example in 1986 in Startup fever, one could read “The Silicon Valley has been called “one of the last great bastions of male dominance” by the local Peninsula Times Tribune. […] They are under-represented in management and administration. Few women have technical or engineering backgrounds. […] Why there are few women in positioning of responsability in Silicon Valley is complex and puzzling. Until recently, the overwhelming majority of engineering graduates were men. […] Scientific and engineering professionals in the finance community and in start-ups are likely to be men: these power-brokers rely exclusively on their personal networks. […] Twenty of the largest publicly held Silicon Valley firms listed a total of 209 persons as corporate officers in 1980; only 4 were women. The board of directors of these 20 firms include 150 directors. Only one was a woman: Shirley Hufstedler, serving on the board of Hewlett-Packard.” But the authors are optimistic: they explain that any woman with a technical background or an interest in high-tech has opportunities: “A Martian with three heads could find a job in Silicon Valley. So for women with a technical background, it’s terrific. […] An exception to masculine dominance is Sandy Kurtzig. “I wanted to start in a garage like HP, but I didn’t have one. So I started in a second bedroom of my apartment.” At first, Kurtzig did sales, bookkeeping and management of her start-up. As long as she had only five or six employees, they worked out of her apartment. It went into rapid growth and had annual sales in 1982.”

And what about Anna-Lee Saxenian in 1999 : “In 1979, I was a graduate student at Berkeley and I was one of the first scholars to study Silicon Valley. I culminated my master’s program by writing a thesis in which I confidently predicted that Silicon Valley would stop growing. I argued that housing and labor were too expensive and the roads were too congested, and while corporate headquarters and research might remain, I was convinced that the region had reached its physical limits and that innovation and job growth would occur elsewhere during the 1980s. As it turns out I was wrong.” Returning to the earlier statement (France has moved very quickly, not to say too quickly, from a lack of understanding to a criticism of this world without grasping the reasons for its appeal and success), I believe it is essential to read and reread the remarkable works of Professor Saxenian (Regional Advantage, The New Argonauts). She has been able to explain the reasons for these attractions and successes, which persist today despite the excesses.

I’ve arrived at these compromises, which the great Bernard Stiegler helped me develop:

– In a 2016 post, “Has the World Gone Mad? Perhaps…,” I wrote that Stiegler’s main thesis is that capitalism has gone mad and that the absence of regulation and controls can lead to madness. “Disruption” can be beneficial when followed by a period of stabilization.

– That same year, in “Disruption and Madness According to Bernard Stiegler”, I noted that in ancient Greece, the term Pharmakon referred to both remedy, poison, and scapegoat. Medicine becomes harmful if consumed in excess…

I will therefore read Marion Flécher’s book with great interest and will write to you in a future post to see if I find cause for resignation or optimism regarding the startup world.

Post-scriptum: I regularly wonder about the nature of French society’s relationship with science and technology. All the pitfalls of technology are clear, and I regularly mention them here; for example, I’m thinking of François Jarrige’s *Technocritiques*. I’m not sure that the criticism is as severe for science or mathematics, as if they were more neutral. We hear less often about the fact that very few women have been Fields Medalists: two female laureates in 2014 and 2022, compared to 80 laureates in total since 1936.

Science in the media is neglected in France, generalist journalists and even French intellectuals have a rather deplorable scientific culture. Science doesn’t attract many girls, or at least they are discouraged from pursuing it for complex reasons. This wasn’t the case in the former Eastern Bloc countries (whatever the reasons may be). The relationship with technology, and therefore with innovation and startups, is perhaps a consequence of this, or simply a correlation. This might explain some of my sadness or frustration, even though I haven’t lost my enthusiasm. And in those moments, Churchill’s quote comes back to me: “Success is going from failure to failure without losing your enthusiasm.”

Two references in French.

– Mathématiques : deux femmes récompensées depuis 1936 : https://www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/article/2019/03/20/mathematiques-deux-femmes-recompensees-depuis-1936_5438858_4355770.html

– Maryna Viazovska, deuxième femme lauréate après Maryam Mirzakhani : https://information.tv5monde.com/terriennes/medaille-fields-maryna-viazovska-deuxieme-femme-laureate-apres-maryam-mirzakhani-2933

Nexthink, a Lausanne-based startup, acquired for 3 billion dollars

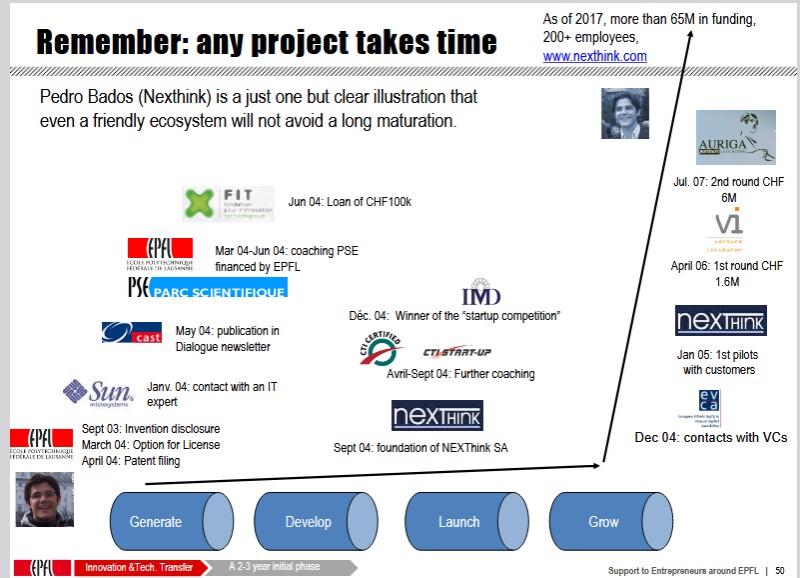

This doesn’t happen that often in a lifetime [1], so it deserves a pause: Nexthink, a spin-off from EPFL, has just been acquired for $3 billion [2] — you read that right, $3 billion!! Admittedly, Nexthink isn’t exactly young anymore; it was co-founded in September 2004, by Pedro Bados, who came (I believe, to do a master’s internship as part of the Erasmus program) in the artificial intelligence lab. AI wasn’t what it is today. His project was based on Bayesian methods… As luck would have it, I met Pedro then to analyze the intellectual property he had generated and what could be done with it. Pedro wanted to sell the patent that EPFL had filed, and when he discovered it wasn’t generating as much interest as he had imagined, I suggested, “Why not a startup?” That became my main role. I also helped him structure the initial deal, I mean who he would work with, within EPFL and outside, and made some introductions at the time. The rest is history !

Pedro has become a discreet but essential figure in the Swiss ecosystem [3]. He was our guest for ventureideas as early as 2006, along with Jordi Montserrat.

Here are notes taken at the time from his présentation (pdf).

NEXThink notes

He also gave a beautiful interview ten years ago to the newspaper Le Temps (in French): Nobody is ready to be an entrepreneur

I’ve had some wonderful experiences in my professional life, in scientific research first between Paris and Stanford University, then in venture capital with Index Ventures, finally at EPFL for 15 years, and for the last 6 years at Inria. Nexthink will certainly remain one of the best ones, and I hope to experience a few more. As I said 15 years ago [4], my professional passion is to encourage these kinds of ventures (see the Stanford interview): “A love of entrepreneurship, a passion that I took back home to Europe after studying here [at Stanford University]. I want to see a stronger entrepreneurial culture there, and I am working in more than one way to effect that change.”

A few notes:

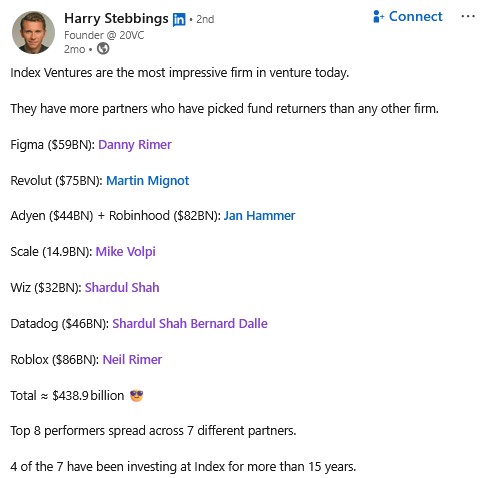

[1] I was struck some time ago by this post about Index Ventures and its stratospheric performance :

8 startup with an exit above $10B : Figma – $59B, Revolut – $75B, Adyen – $44B, Robinhood – $82B, Scale – $14.9B, Wiz – $32B, Datadog – $46B, Roblox – $86B. So what does $3B represent for Index? And I don’t have a list of their exits above a billion. I remember Virata, Numerical Technologies, The Fantastic Corporation, and Skype before 2005. I might ask them!

[2] Some more news and archives – What I found online about Nexthink acquisition, mostly LinkedIn posts by its founders and investors as well as press articles

Nexthink News autour acquisition

Neil Rimer (Index ventures) and Pedro Bados I am not sure where and when

[3] A short presentation of the EPFL ecosystem to its alumni before 2010 that mentions Nexthink (pdf)

a3angels10-herve_lebert-innogrants[4] Thanks to my favorite search engine, an exchange about what I thought of startups, Silicon Valley in 2008 where I mention Nexthink. I am not sure things have changed that much…

Stanford HLWhy is Silicon Valley Silicon Valley ? A debate initiated by AnnaLee Saxenian

I should go back to Silicon Valley to ask AnnaLee Saxenian what she thinks of Silicon Valley today and, more importantly, if her analysis is still valid today (which I think it is !)

I fall by accident on a short 6-page article that she wrote in 1999 entitled Comment on Kenney and von Burg,‘Technology, Entrepreneurship and Path Dependence: Industrial Clustering in Silicon Valley and Route 128’ that you can easily find on the net, for example on Researchgate.

Why do I care about a 25-year old article about innovation ? Because I often have the feeling Europe and France in particular miss the point about what matters. Saxenian’s argument can be summarized with an extract from that article: It is precisely the openness, multiplicity and diversity of interconnections in Silicon Valley that allows economic actors to continually scan the environment for new opportunities and to invest in novel technologies, markets and applications with unprecedented speed. The autarkic structure of firms and institutions in Route 128, by contrast, have historically discouraged precisely the decentralized flows of information, skill and capital that encourage such technological experimentation. [Page 5]

The analysis is subtle because one might get the impression that Europe has understood the role of collaboration, but I fear that it has remained institutional and not informal. Has there ever been a Wagon Wheel Bar in Europe?

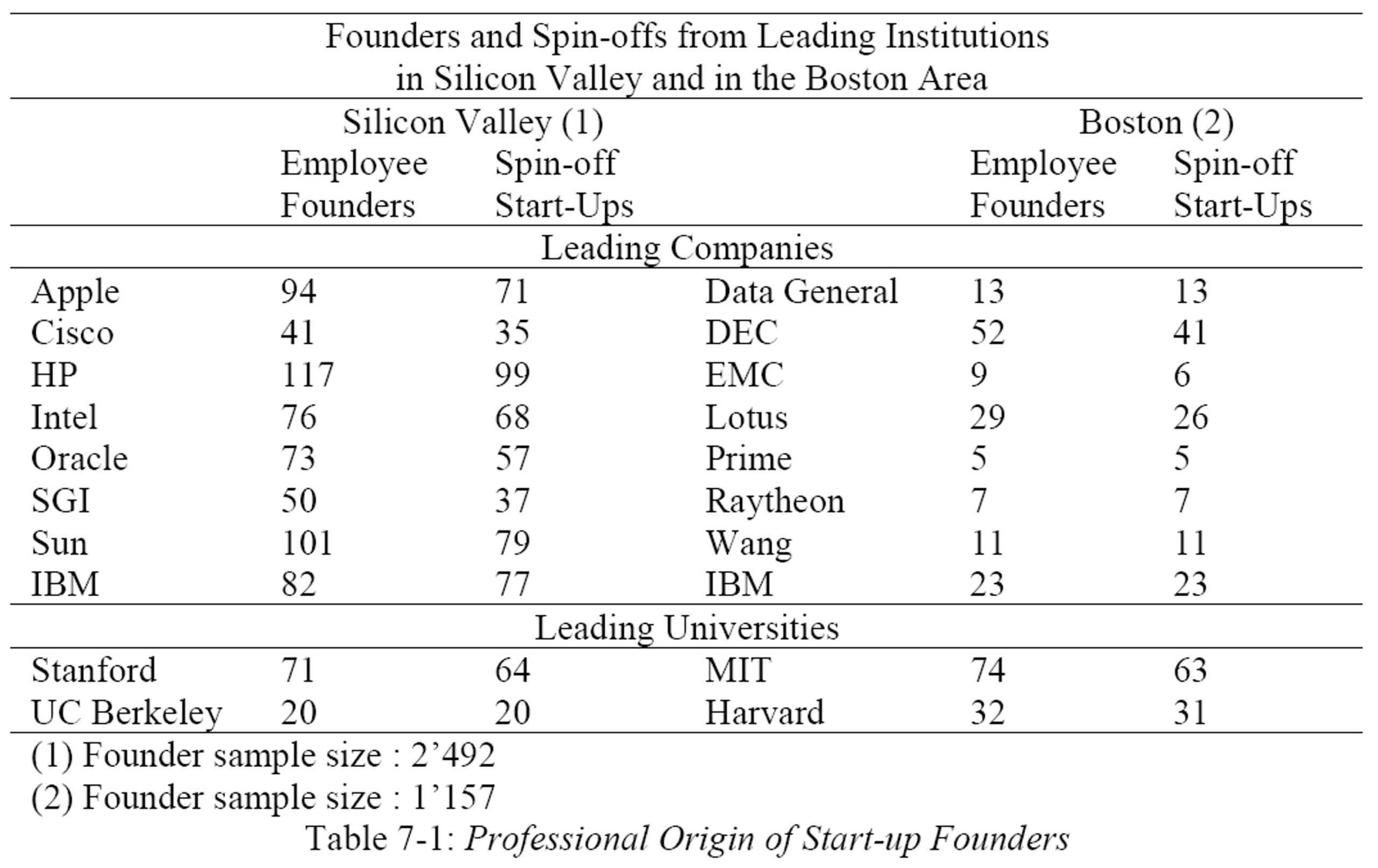

Again the article is short and worth reading. The debate is also about the role of big firms in technology clusters. The figure which follows is a perfect illustration:

Source: J. Zhang (2003) compiled data from VentureOne based on VC-backed spin-offs from 1992 to 2001

Zhang had worked with Saxenian and the table shows that from an academic standpoint, entrepreneurship was as strong at MIT/Harvard as Stanford/Berkeley. But if we just look at IBM West vs. IBM East, the difference is striking. “Individuals in Silicon Valley regularly leave jobs at established firms to join start-ups, and vice versa, all the while maintaining networks of cross-cutting personal and professional relationships. Nor is it uncommon for individual engineers working at large firms to make angel investments in promising start-ups — or for established firms to organize venture divisions to support new ventures in related industries.” [Page 4]

I have been using it since I discovered it years ago, particularly when I was giving classes about startup and Silicon Valley. With a little nostalgia, I put my introductory pdf below where I emphasized on the role of culture in entrepreneurship.

eLab01 - SiliconValleyDeeptech Startups and their Challenges in France (continued)

As indicated in my previous article, I preferred to cut out my summary of the workshop on the subject “Deeptech: are we ready to scale?” organized by Inria during the Vivatech trade fair

If the first round table spoke about bipeds, the second was about ecosystems, about “rain forests” more than “French gardens”!

Antonin Bergeaud, I listened to you when you received the award for the best young economist in France, particularly about technological innovation, on France Inter and France Culture and you said at one point that you were drawing a parallel between your childhood dream of being an astronomer and your situation as an economist by saying that you wanted to understand the complexity of the world but that in the economy, there is the human factor which there is not with the stars. Is that our challenge or are there other elements that interest you so that we have European Gafam tomorrow?

“We have the impression that the level of complexity is really in hard sciences but in the human sciences there are a lot of interactions that make things very complicated and in particular because we have little regularity so we have to deal with the fact that there are biases. Like what was mentioned that in Europe we are less enthusiastic than the Americans, but we don’t know how to measure this very well. There are a lot of features that we have to take into account and since the challenge is to try to inform and shed light on why we have such difficulties, for example having a Tech sector that is of the same magnitude as the one we have in the United States or why companies have difficulty obtaining financing in Europe, we are obliged to take into account all these dimensions and it is true that it is quite complicated, so that is a bit where the parallel ends, it is that it is complicated. I think that now there is a kind of consensus beginning on the structural difficulties that we have in France and in Europe, which does not mean that we are going to correct them but at least we are beginning to understand a little better what is happening.” […]

– we don’t have enough entrepreneurs and we don’t have enough engineers trained in France and Europe […] there’s a real training issue that needs to be addressed, largely because you have a lot of losses, a lot of entrepreneurs and engineers leaving for the other side of the Atlantic.

– the second difficulty in Europe, because all the French problems are quite real everywhere in Europe, is getting universities to connect with businesses. For example, all patents filed by all companies in the world must provide the academic references they use in the patent description, and what we see is that for certain technologies, where Europe is practically non-existent in terms of technology production and marketing, we are actually relatively dominant or at the same level as the United States in the production of ideas, except that these ideas are not cited by French or European patents; they are cited by Chinese or American patents. So, basically, we have scientists and researchers who produce very relevant ideas, including on very, very recent technologies, and ideas are supposed to circulate freely. They circulate freely, but they circulate a lot from Europe to other countries, and a little less in the other direction.

– the third problem is indeed financing, which was discussed a lot earlier. I think that in Europe we have a relationship with risk that is really specific to our continent. Perhaps it is not necessarily negative, and I don’t think we should necessarily give it up, but we must be aware that it poses a certain number of difficulties in growing companies quickly, particularly in disruptive technologies, because we tend to move more towards bank financing, because we have less venture capital funding, because we have a market that is very fragmented, particularly in terms of financing innovation, and because we have institutions and regulations that are much more restrictive, at least from a growth point of view, than what is done in the United States.

Paul Midy, I could call you Mr. Start-Up at the National Assembly. What would you like to add?

“I would put the issue of financing number 1 by far. Fundraising in Europe seems to be three times lower than fundraising in the United States, even though we are generally roughly the same size, we generate roughly the same GDP. When you put your money into a company like Mistral, a deeptech company, you don’t get it back the following year, it’s at least 20 years later that you get it back; it’s long-term capital. And this long-term capital exists mainly in retirement capital, and so I would say that the number 1 factor is the fact that we have a pension system in France, and many in Europe too, which is a pay-as-you-go system that is not a capitalization system. We don’t have pension funds or we have very few. We have to realize the enormous gaps that this generates in France. Long-term savings and what can look a bit like capitalization are 200-300 billion euros; if I take the whole European Union, it’s 6,000 billion and essentially it’s the democracies of northern Europe at 70%; if I take the United States it’s 42,000 billion. You can supply a New York Stock Exchange with 25,000 billion and supply a Nasdaq with 25,000 billion and on the other side in France you have Paris the Paris Stock Exchange 3,000 billion Frankfurt 3,000 billion London 3,000 billion so we have a stock of capital which is much less important and so for fundraising the result of all this is that our start-ups last year raised 50 billion in the United States it’s 150 billion. […] I call for us to make a CIP, a common innovation policy at least as ambitious as the CAP, the common agricultural policy. A third of the budget of the European budget is the CAP. Another third is the social cohesion funds. Very important. Innovation is less than 10% of Europe’s budget. It must at least be three times more immediately. […] I am a politician, so we are trying to change the system. Either we say to ourselves, it’s a culture, that’s how Europeans are, and they like risk less, they are a little more grumpy and everything, and so there is nothing to be done. I can’t accept that, so I’m trying to understand why the Americans are in a different situation; it’s not genetic. I think we need to set ourselves the goal of making Europe the richest, most prosperous continent in the world, therefore the most innovative, capable of defending itself, and then everything will flow from that.

Alexis Robert, you work for Kima Ventures, which is Xavier Niel’s fund, whose recent book “Une sacrée envie de foutre le bordel” (A Real Desire to Cause Trouble) I read, and which sometimes puts himself at odds with the system. Do you also, by working for the Kima Ventures fund, have a slightly more atypical view of these things, or how do you want to build on what we just shared?

“In fact, what happens when you are early stage, while what you mentioned is true in late-stage for Series B financing and above, but in fact today what we see is that in the seed rounds, preseed/seed there is in fact a little too much capital, and in fact today the VCs, the problem that there is and why we have difficulty finding GAFAMs is if we actually go back to the history of French venture capital, in fact they are spin-offs of banks and then over time they actually recruited the sons of their LPs [Limited Partners] or people who were in their network or people who thought like them who actually have a finance mindset. There are very few engineers, very few scientists who are actually in these VCs. […] To create GAFAMs, to create for example openAI, Sam Altman comes from the world of Computer Scientists, look at Elon Musk, he is a Computer Scientist, you look at Mark Zuckerberg, he is a Computer Scientist, and in fact to create the GAFAMs of tomorrow it will actually come from people who have a strong scientific culture or who have cultures that are different it can be people who perhaps did not graduate from engineering schools, people who are very different but the VCs are stuck in a mindset and the people in the ecosystem in general too. […] For example Mistral at the time when Arthur Mensch, Guillaume Guillaume Lample and Timothée Lacroix did their first fundraising, uniformly all the VCs all said ah yes what they do is great “yeah but hey they are researchers anyway”, they do not know how to break out of the mold of CEO who went to HEC.”

Mehdi, we supported you at the start-up studio, but before talking about business, we’ll come back to that later. I remember maybe you don’t want to talk about it too much, but you wrote a wonderful essay on what a functioning ecosystem is for entrepreneurship. I reread it two days ago, it was in 2017 I think. Do you have the same vision of the ecosystem’s weaknesses and what a country must do to promote people like you 8 years later?

“So yes, and even more unfortunately, even more so, and I’ll explain why. Yes, money is an issue, but even Sam Altman today, who is at the head of OpenAI, who has just made, who has just said that he has an annual turnover of 10 billion, has financing problems. But for me, the problem, the big problem in the ecosystem, is ambition, it’s the ambition of European entrepreneurs. In California, he would tell you, “I’m going to change the world,” they have an ambition that has no limits, and be careful, it’s not genetic, they are trained for that, they have accelerators like Ycombinator, they have advisors, they are often coached by other entrepreneurs who have had exits or who have made very large companies, and they are fueled by ambition, which I think we lack here. [What’s also missing] is investors who also work on feeling, who work on entrepreneurial ambition, who will go and fight for a billion or a hundred billion dollar case. Money is not the main problem for me because there is money, especially in seed funding in France with the BPI. After that, it is the ambition that must match, and the execution of course, the execution is not simple, but Arthur Mensch raised 100 million on slides in 3 months because he had an ambition at that time. “Unfortunately in Europe we are still in an ecosystem where we make technology with money where others make money with technology.” […] Sam Altman coached close to 1000 startups when he was at the head of Ycombinator, he saw an ecosystem, he saw innovators, he trained himself, that’s why today he says we will make a generative AI, an AI that will be a company that makes 1 billion, a person will be able to make a billion in value thanks to an AI and a only employee but because they are trained. Now look these are what Alain Damasio calls hyperstitions [https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/hyperstition] we are beyond superstition sometimes, we fall into lies, we fall into ideology so we in Europe we are a little more careful. [In the USA we say] “go for it, go for it, we support you, we will go with you” but today I do not know anyone in Europe who would act like that because they are trained in the USA. It is really an INSEP of entrepreneurs that we need.” […] Entrepreneurship is like playing poker you have cards in hand and then there are cards that arrive and as you go you have to adapt. We need people who will free us up, not just as entrepreneurs!, but who will free up the bandwidth to be able to understand what is happening. For me, these are advisors who have made the Champions League.”

Alexis Robert: “I am very aligned with Mehdi […] there are [so many people who] reject you because in fact you do not speak in the languages of the mold. In fact that is the problem today, is that in fact the entrepreneur feels alone and certain types of entrepreneurs who have a scientific and technical background do not know where to turn and today what is happening in San Francisco, what makes San Francisco great, is because in fact you get off the plane directly you have the feeling of being accepted as a geek, you have the feeling of being at the right place, you have “role models” who are there for you, who pull you up, you have the feeling that you too can be able to do this and in addition there is a sense of community which is extraordinary; you arrive, you are in the street, you speak with a VC, well, he listens to you or not, you have Sam Altman who passes in the street and you can say hello, you sit in a cafe and you talk, you have entrepreneurs to talk to, speaking is easy, introductions are easy and fluid, you can surround yourself with people who allow you to learn and improve because, as was said in the first panel, if you have understood general relativity, succeeding in pitching is not very complicated, you will succeed in doing it and in fact that’s what I wanted to say.”

I stop here and the people said much more. This is unfair not to share everything… But I think it gives you a feeling of what are challenges and opportunities are !

The Tour Triangle designed by Herzog and de Meuron, at the exit of Salon Vivatech, see also Instagram

Deeptech Startups and their Challenges in France

During the Vivatech trade show, Inria organized a workshop on the topic “Deeptech: Are we ready to scale?”

The discussions were rich, in-depth, and fascinating. I’m obviously biased since I was a co-organizer, but I’ve rarely had such a pleasure discussing the topic. So, I’ll provide a subjective summary, adding my own comments on various topics that are dear to my heart. [They will be in brackets and italics.]

What is Deeptech?

This was the starting point for Théau Peronnin, founder and CEO of Alice & Bob. “Above all, it’s a technology that has two fundamental attributes: the first is it has very deep roots in science. If you can understand this technology straight out of business school, it’s perhaps because it’s not quite deeptech yet. […] Its second attribute is the ability to create companies, players, or products that will have a strategic impact on the economy.”

[During another roundtable, I heard that the term appeared when the internet, B2B/B2C, and SaaS had diluted the technology into the excesses of “pet.com”, but that fundamentally, the high-tech of the 1980s and the deeptech of the 2010s are two sides of the same coin. I would add that if something is patentable, it’s undoubtedly deeptech.]

Théau Peronnin then gave his perspective on the challenges facing the French ecosystem. “I can tell you very simply: in France, we are extremely strong on the initial opportunity, we have incredible talent. We are still tied for first place in the number of Fields medals with the Americans, even though we are five times fewer in number.” […] “And then we have an early-stage venture capital ecosystem that has managed to establish itself in recent years, perhaps even a little too much; we could finally say that it is slightly saturated.” […] “The weaknesses are really in the later stages of a deeptech’s life. We have a subject that is perfectly known but which is far from being cracked, which is that of financing the so-called growth stages, this moment when companies like Alice and Bob will seek to raise capital of several tens of millions of euros, several hundreds of millions of euros to continue this R&D race at the international level.” [This is a subject that will be addressed later and I am not sure that it is the main subject, but the debate undoubtedly exists. See below!] “There are no suitable European players, which creates an anticipation effect across the entire value chain and there is a certain reluctance among funds to really deploy this capital with intensity and audacity in deeptech.” […] “Silicon Valley takes its name from the deeptech of the 70s, 80s, 90s in silicon, which created generations of fortunes of individuals with a very strong appetite for this deeptech and who therefore subsequently directed their capital towards these investment funds which continue to invest in this field. In Europe, there are no such fortunes, they were made elsewhere, they are in other fields and therefore we do not yet have these good products, hence the important role of the State in priming the pump.”

“One last point to introduce the round table on the human factor, which is the relationship to risk-taking. France has a school in any case, a view of studies and the academic world very focused on excellence which is perhaps the downside, or rather the cliché, of saying that we have a certain fear of failure and this is seen in my opinion in certain systems which deserve to be rethought, notably that of the Pacte law for the part-time activity of researchers and there it is a very personal opinion that I wish to share with you which is that of saying that there is no entrepreneurship without risk-taking. You have to get your hands dirty, you have to put your career on the line somewhere, you have to have “skin in the game” as the Anglo-Saxons say and perhaps in this system there is therefore in this part-time activity, a comfort in knowing that you are still well protected within your research organization while trying to enjoy the pleasure of entrepreneurship. In my opinion, we have to go all out and that means being able to come back to the academic world after a startup failure and so perhaps the lever to allow more audacity is to make the academic world more attractive for profiles with hybrid careers that have gone through the world of entrepreneurship. That’s to launch this round table on the theme of the human factor, these men and women who are making the entrepreneurs of tomorrow.”

Deeptech is, above all, about bipeds!

Théau Peronnin returned to the subject of humans through a real problem: “A very difficult issue we have is that of parity, gender diversity, which is horribly difficult to crack because we arrive at the very end of the food chain for training these profiles. Above all, technical profiles, a lot of self-centeredness regarding the fact of going through the Grandes Ecoles with all the sociocultural bias there is in these Grandes Ecoles, and even with international diversity, we must have between 20 and 30 nationalities, 30% of non-French speakers in the team, so this gives you a little demography.”

Xavier Duportet amplifies this human aspect: “We have people who are a little crazy because to get started in deeptech [where] less than 2% of projects reach a mature product on the market […] to get started you have to be a little crazy, you have to be naive too, I think, and you have to think that what is impossible can become possible. There are lots of things we don’t know and so the unknown is part of our daily work.” […] “The most important thing for us is not necessarily experience, it’s above all curiosity and that people are enterprising because in deeptech you can’t just apply the principles, apply the things you’ve already learned, you always have to be ready to face failure almost every day and so you need people who are willing to question themselves and who deep down are truly enterprising people.”

Jean-Michel Dalle: “There are motivated bipeds who come to talk to us about the microbiome, or motivated bipeds who come to talk to us about quantum computers. Anyone who doesn’t see things from that perspective, that is, from the bipeds’ perspective, is missing something. Of course, we’re going to check that the quantum computer project isn’t just anything, that they didn’t invent it on a Sunday morning after the market. But if we don’t look at it through the eyes of the founders, in my opinion, we need to change careers.”

Théau Peronnin: “The real issue is that the researcher’s passion is to understand, but the problem with that is that we reap the rewards of the pleasure of our work very early in the product’s life. I understood what I had to break to bring this machine to market, but unfortunately, we only did 5 or 10% of the work to truly deliver the system.” Behind this, we need to strengthen, produce, distribute, reposition. There is a whole issue: how do we learn to take pleasure not in having understood but in making the other person understand, but even more than that, in making the other person adopt what we have cracked, and that is a muscle to develop which is quite different.

Xavier Duportet: “It’s not a technology, it’s not a science that’s going to change the world or save the world, but a product, and that’s often where it falls short. We still see a lot of researchers who only think about science, only technology, and who can’t make the switch in their minds, saying, ‘How come I’m not selling my science, but I’m making people dream, I’m making these serious people [investors] dream, that I’m going to be able to be that person who will transform science into a product that will generate added value for society, but above all, for investors.'”

Marie Paindavoine: “I was lucky at the beginning to be supported in entrepreneurship by structures from the academic world, first by INRIA and then by the University of Berkeley in the United States, which has an acceleration program, and it’s true that thanks to them, it allowed me to learn how to transform this scientific discourse into an entrepreneurial discourse; and moreover, at the acceleration program at the University of Berkeley, for six months, we just repeat the company pitch and learn how to convince, in fact, because ultimately, and they tell us, ultimately, you’ve done the hardest part, you have great technology, you’ve managed to write a thesis in cryptography, well, you’ve done the hardest part, Marie, now learning marketing will take you two months, but you have to get down to it for two months, and that’s where we need to surround ourselves, to have this ecosystem that allows people to train because, after all, if we’ve managed to do a doctorate, we’re able to continue to train in the profession of entrepreneurship, but we need to find those people who can see not the value of scientific technology as it can be presented today, but a sort of projected value of this technology.”

Xavier Duportet: “On people and the network and the ecosystem, I also had the chance to do a thesis between INRIA and MIT. At first I wanted to be a researcher and when I arrived at MIT, I saw all these people who were starting up, these professors who were becoming entrepreneurs, that’s when I understood I was inspired by this generation of entrepreneurial researchers saying to myself but in fact if we really want to change the world it’s not research it’s entrepreneurship and today in the US, there is Silicon Valley, it was created 20 years ago, 30 years ago as Théau said there is this whole generation now, not grandpas but slightly older people who have succeeded and so in fact there is a “network effect” in the US which is super important, it’s the generation of entrepreneurs who have already succeeded who are there to help and pass on they did it they made mistakes and they really serve as mentors and that’s where we have a pretty interesting opportunity, and in France we can’t want to put the cart before the horse, we have what the BPI has done, all the research institutes, the change that has been underway for 10 years, we are starting to have these companies which are becoming leaders on the international level.”

Matthias Schmitz: “What we have started to do recently is to invest in an entrepreneurial mindset much earlier in the education of our students so we are trying to roll out programs where we bring entrepreneurship into all the faculties. For example, the university of Saarland is investing €1.5M every year with the goal that every single student that we have, whether it is a business student, whether it is a Romanistic student or an engineering student has at least one time during his studies thought whether entrepreneurship can be a career option for himself and by doing that I think we try to solve the problem a little bit earlier, bring the mindset in the heads of the people and not having to have people jump into the too cold water at the moment where they are already at the PhD level.”

Marie Paindavoine on being a female entrepreneur: “do you want the version we hear in France or the United States? both! So we don’t hear the same thing in France and in the United States. In France, I was immediately asked if I intended to partner with “un” CEO, emphasizing the “un”. I was already asked after my presentation, well, anyway, I’m not going to do them all actually because it’s of no interest, but there is indeed a halo of suspicion, let’s put it like that. In the United States, then I’m not saying that they are better than in France because I arrived at the University of Berkeley, at the University of Berkeley accelerator, 2,000 applications, 30 start-ups selected, 2 women CEOs, so they are not much better. On the other hand, once we reach this level of selection, when I say I’m starting a business with children, people tend to congratulate me on the level of energy it requires instead of asking me how I’m going to arrange childcare and if my husband agrees with me starting a business with my children, something I’ve already been asked in France.

I’ll stop here and do a new post about the second roundtable!

Silicon Valley : The Collapse?

Excellent issue of FUTU&R, the magazine by Usbek & Rica, which main feature is entitled Silicon Valley, Chronicle of a Collapse. It’s not a good time to be a fan of the region these days. If you follow my blog, you’ve seen my struggles to understand what’s going on there. This issue contributes to this, and you’ll discover dubious characters like Curtis Yarvin, Balaji Srinivasan, Palmer Lucky, in addition to the famous Peter Thiel, Marc Andreessen, David Sacks, and even Larry Ellison. The issue is a bit biased, but that’s the name of the game, since the magazine “imagines how the Tech Eldorado could collapse.”

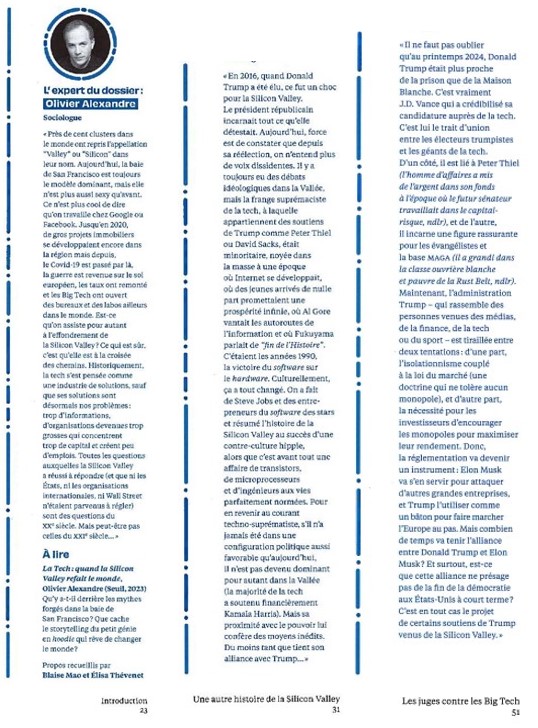

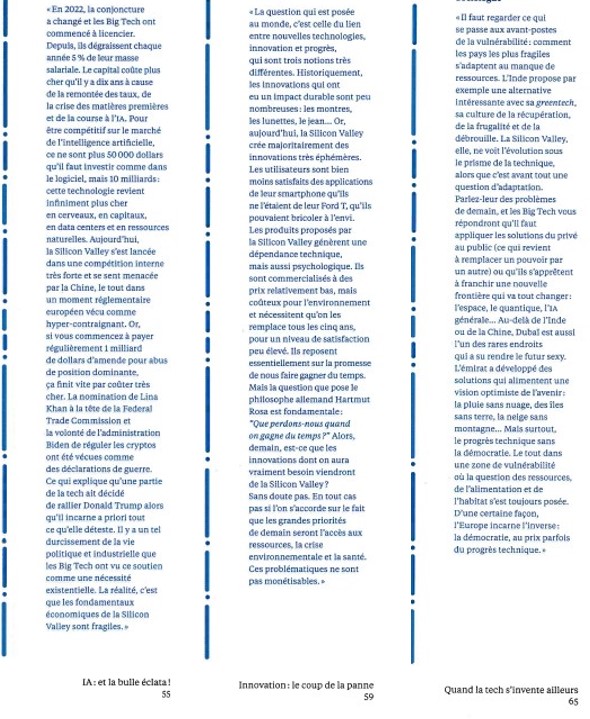

The magazine had the good idea to add the informed opinion of Olivier Alexandre, often mentioned on this blog, notably as the author of La Tech. I scanned the contributions in low resolution and I hope the magazine will forgive me for this breach of copyright. I obviously encourage you to buy a copy!

I will just comment on what Olivier Alexandre says and I will end this post by discussing a related subject through a fairly recent scientific article, The Role of Universities in Shaping the Evolution of Silicon Valley’s Ecosystem of Innovation (pdf)

“Are we witnessing the collapse of Silicon Valley? What is certain is that it is at a crossroads. Historically, tech has thought of itself as a solutions industry, except that its solutions are now our problems. […] It is clear that we no longer hear dissenting voices. There have always been debates in the Valley, but the tech supremacist fringe, to which Trump supporters like Peter Thiel and David Sacks belong, was a minority, drowned in the mass. […] Steve Jobs and software entrepreneurs have been made stars and the history of Silicon Valley has been reduced to the success of a hippie counterculture, when it is above all a story of transistors, microprocessors, and engineers with perfectly standardized lives.”

Indeed, the region was a republic of engineers, with back-and-forths between fierce competition in a global world and deregulation and occasional isolationism allowing monopolies. In the 1980s, the threat was Japan, and the semiconductor industry had appealed to the Federal State for its survival (after having benefited from the flow of public money at the height of the Cold War in the 1960s.) I recently spoke of my difficulty in finding dissenting voices too.

“In 2022, the situation changed and Big Tech started laying off employees. Since then, they’ve been cutting 5% of their payroll every year.”

On this point, I slightly disagree with the observation. In 2009 and 2013, for example, Google also reduced its workforce by 5%. I had heard that Cisco was shedding 5% of its “lowest-performing” workforce each year. The region was so dynamic that it was rarely discussed. Working conditions have always been “harsh and demanding.” A world of engineers, no doubt. It brought us computers and smartphones, the internet, and therefore opportunities to behave differently. It also contributed to creating immense biases because, without a doubt, the use of science and technology is never completely neutral.

“The question being asked of the world is the link between new technologies, innovation, and progress, which are three very different notions. Historically, innovations that have had a lasting impact are few: watches, eyeglasses, jeans… However, today, Silicon Valley mostly creates very ephemeral innovations.”

Tom Kleiner went further, mentioning the printing press, the steam engine, electricity, and finally the transistor as innovations that changed civilization. This is undoubtedly close to reality.

And Olivier Alexandre adds a beautiful question: “The products offered are essentially based on the promise of saving us time. But what do we lose when we save time?”

And he concludes (provisionally): “Dubai is one of the rare places that has managed to make the future sexy, an optimistic vision of the future: rain without clouds, islands without land, snow without mountains. But above all, technological progress without democracy. All this in a vulnerable area where the questions of resources, food, and housing have always arisen. In a way, Europe embodies the opposite: democracy, sometimes at the cost of technological progress.”

This isn’t the first time that the future of Silicon Valley has looked bleak. For example, you can find AnnaLee Saxenian’s predictions in a post titled Is Silicon Valley crazy (again)?: “In 1979, I was a graduate student at Berkeley and I was one of the first scholars to study Silicon Valley. I culminated my master’s program by writing a thesis in which I confidently predicted that Silicon Valley would stop growing. I argued that housing and labor were too expensive and the roads were too congested, and while corporate headquarters and research might remain, I was convinced that the region had reached its physical limits and that innovation and job growth would occur elsewhere during the 1980s. As it turns out I was wrong.”

There’s no doubt the region is at a new crossroads! But I’m not finished yet, see below.

I promised above to talk about a scientific article dating from 2020. I found its conclusion interesting even if overall the content well-known. So I copy paste :

Silicon Valley—a Metaphor in search of a Structure?

Silicon Valley is a metaphor for a region that lacks a viable governmental structure. It is at the stage of New York, before its 1989 consolidation into a unified city. With the notable exception of the ecology of the Bay, a downside has emerged, a public-private imbalance revealing gaps in housing and transportation Spread across multitudinous counties, towns and cities, Silicon Valley lacks sufficient governance capabilities to address the negative consequences of its overweening success.

An additional imbalance in academic capacities is, in part, a consequence of a more than half century old master plan strictly segmenting the public academic sphere that has limited individual institutional advancement. This gap has been partly redressed by establishment of branch campuses by universities in other parts of the country, like Carnegie Mellon and the Wharton School that ironically treat the region as an under-developed area, at least in its academic capabilities. Moreover, state government funding for public universities

has declined drastically, from providing 40% of Berkeley’s budget in the 1980’s to 14% percent at present. This gap is being redressed by a massive fund-raising campaign that expects to raise 6 billion dollars and increase the universities tenure track positions in coming years.

Re-balancing the Triple Helix will also require increased interaction among the spheres, a phenomenon that has declined in recent decades, placing the long-term innovation and carrying-capacity of the region at risk. The innovative and sustainable economic development of Silicon Valley not only depends on the presence of strong universities, but on how they interact and overlap roles with the other agents of the Triple Helix model, looking for mutually strategic objectives and identifying cross-cutting issues which none of them can adequately deal individually. Interactions between university, industry and government in a highly dynamic and volatile environment, represent a unique opportunity to recover from economic downturn, create new jobs, and promote a prolific, inclusive and economically sustainable development of regions in the long run.

Who in tech still has the courage to publicly oppose Trump in Silicon Valley?

In recent weeks or months, I have been discovering with amazement or embarrassment that many people in Silicon Valley have apparently turned their backs to support Trump’s policies in the United States. It’s quite impressive, even if it’s not as impressive as we think. I already addressed the topic in July 2024, at a time when I believed Kamala Harris would be elected president. It was titled Politics and Silicon Valley. And I indeed discovered that former Democrat “sympathizers” were turning to Republicans such as Mark Zuckerberg, Sam Altman, or Marc Andreessen. Worse, it seems that even Sundar Pichai (CEO of Google) or Tim Cook (CEO of Apple) were going in the same direction. After all, in Europe, we are never shocked that a boss is right-wing and the least favored are left-wing. Again, you can reread my post on the subject. In reality, Silicon Valley is so Democrat in its voting that it was perhaps difficult to position oneself otherwise, and today, people position themselves more openly. Votes are also evolving as illustrated here.

So I asked myself the question: who is opposing Trump today in tech and Silicon Valley?

I was pleasantly surprised to find that there were figures like Bill Gates and Michael Moritz:

– Bill Gates is a moderate and not active politically. But I quote him from Bill Gates says he’s surprised about his fellow billionaires’ rightward political shift: ‘I always thought of Silicon Valley as being left of center’ : “The fact that now there is a significant right-of-center group is a surprise to me.” while “incredible things happened because of sharing information on the internet,” social media has had major downfalls. “You see ills that I have to say I did not predict,” While Gates is by no means an open Trump supporter, he said he’d do his best to work with the president. “I will engage this administration just like I did the first Trump administration as best I can,” Gates told the NYT.

– Michael Moritz is less well known, but given that he funded Google, Yahoo!, PayPal, Apple, Cisco, and YouTube, we can appreciate what he has to say in Trump’s tech backers are ‘making a big mistake,’ Trump’s tech financiers and supporters were “making the same mistake as all powerful people who back authoritarians.” He wrote that wealthy financiers believe “they will be able to control Trump,” or else are committing “another cardinal error: deluding themselves that he will not do what he says or promises.” “That has not been the modus operandi of authoritarians over the centuries,”

Paul Graham, whom I respect, wrote an article on wokeness that deserves careful reading, but it’s not really an opposition to Trump; rather, it seeks to explain a movement. Please read The Origins of Wokeness. For example I’m not going to claim Trump’s second victory in 2024 was a referendum on wokeness; I think he won, as presidential candidates always do, because he was more charismatic; but voters’ disgust with wokeness must have helped. And “Trump and wokeness are cousins”.

Steve Blank is rather silent but I discovered that in 2020, that he resigned from a Department of Defense advisory board, protesting the Trump administration’s decision to oust most of his fellow board members and replace some of them with political loyalists with no defense or business experience. See here.

Who else? I’ve searched a bit in vain. My “heroes” are rather silent, but they always have been, so what can I conclude? Hopefully, some will wake up and dare to oppose them, whatever the cost…

PS: I found a little more, for example, Larry Page: “I intend to tell the president that we are with him and that we will help him in any way we can. If you can reform the tax code, reduce regulations and negotiate better trade agreements, the US technology industry will be stronger and more competitive than ever3, he would be quoted as saying by Andoidsis.

Roger McNamme is another investor: Well, everything about Trump seems like a payback, right? All these executives are giving a million dollars each. These are rounding spreads. This is money they find between the cushions of their living room couch. But, you know, this is essentially a precautionary payment. And in Musk’s case, the investment he made in Trump, which was a quarter of a billion dollars, or the investment he made in Twitter, which was about $44 billion, has paid off, obviously, many, many times over. I think Trump and Musk will eventually part ways. I don’t know Trump at all, but he doesn’t seem like the kind of guy who would support someone who competes on the same level as Musk. But we’ll see how it goes. See here.

And of course, yes, there is Reid Hoffman, the founder of Linkedin, “one of the tech bosses most fiercely opposed to Donald Trump and Elon Musk“. See here or there or again là.

PS2: April 15, 2025. On the day Harvard University rejects Donald Trump’s requests, I just read a few marvelous pages from the Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann. Here they are:

There came a day when Herr Settembrini directly confronted his pupil, and so betrayed his own pedagogic uneasiness. “But in God’s name, my good engineer, he is just a stupid old man. What do you see in him? Can he do anything for you? It is beyond all reason. It would be clear enough — though not necessarily praiseworthy—if you were simply taking him into the bargain, if in seeking out his company you were seeking out that of his current sweetheart. But it is impossible not to notice that you pay almost more attention to him than to her. I implore you, help me understand this.”

Hans Castorp laughed. “By all means,” he said. “Agreed! The fact is, as we know—permit me to say—fine!” And he tried to ape Peeperkorn’s cultured gestures as well. “Yes, yes,” he said, and laughed again. “You find that stupid, Herr Settembrini, and certainly it is vague, which in your eyes is worse than stupid. Ah, stupidity. There are so many different kinds of stupidity, and cleverness is one of the worst. Hello! Why, I think I’ve just coined a phrase, a bon mot. How do you like it?”

“Very much. I cannot wait for your first collection of aphorisms. Perhaps there is still time, however, to ask you to take into account certain observations we have occasionally made concerning the misanthropic nature of paradoxes.”

“It shall be done, Herr Settembrini. Absolutely—shall be done. No, in this bon mot of mine, you do not see me in hot pursuit of paradoxes. I was merely trying to point out the great difficulty one has in defining ‘stupidity’ and ‘cleverness.’ It is so hard to keep them separate, they are so intertwined. I know very well how you hate any sort of mystical guazzabuglio and are a man who believes in values and judgments—value judgments—and I quite agree with you. But the issue of ‘stupidity’ and ‘cleverness’ is at times a complete mystery, and it must be permissible to concern oneself with mysteries, always presuming it is an honest attempt to get to the bottom of them, if possible. Let me ask you this question: Can you deny that he has us all in his pocket? I’m putting it crudely, and yet, as nearly as I can tell, you cannot deny it. He puts us in his pocket, and somehow or other he has the right to make fun of us all. But why? And how? And where does it come from? It is certainly not a matter of his cleverness. One can hardly speak of cleverness in this case, I admit. He is much more a man of fuzziness and feelings, feelings are his cup of tea, so to speak—if you’ll forgive me the colloquial phrase. What I am saying is this: it is not by way of cleverness that he puts us in his pocket, not through intellectual prowess. You wouldn’t stand for that. And it really is out of the question. But surely it is not physical prowess, either! It cannot be because of his broad captain’s shoulders, or any raw brute force, or because he could lay any one of us flat with his fist—it would never occur to him that he could, and if it did, why, a few civilized words would calm him down. And so it’s not physical, either. And yet the physical dimension does play a role, without a doubt—not in the sense of brute strength, but in another, more mystical sense—the moment anything physical plays a role, things always get mystical. And the physical merges into the intellectual, and vice versa, and cannot be differentiated, and stupidity and cleverness cannot be differentiated. But the effect is there, the dynamic effect, and we find ourselves stuck in his pocket. And for that we have only one word at hand, and that word is ‘personality.’ We use the word in another, perfectly reasonable sense, too: we are all personalities—moral and legal and all those other sorts of personalities. But that is not what I mean. I’m talking about a mystery that extends beyond stupidity and cleverness, and that is what we need to concern ourselves with—partly to get to the bottom of it, if possible, and partly, to the extent that it is not possible, to edify ourselves. And if you are for values, then, in the end, personality is a positive value, too, I should think—a more positive value than stupidity or cleverness, positive in the highest degree, absolutely positive, like life itself—in short, a value for life and in that sense suitable for our earnest consideration. And that’s how I thought I should respond to what you said about stupidity.”

Herr Settembrini let silence reign. Then he said, “You deny that you are in hot pursuit of paradoxes. By now you should know that I have an equal dislike of seeing you in hot pursuit of mysteries. By turning personality into an enigma, you run the danger of idol-worship. You are venerating a mask. You see something mystical where there is only mystification, one of those hollow counterfeits with which the demon of corporeal physiognomy enjoys taunting us on occasion. You have never spent any time in theatrical circles, have you? So you do not know those thespian faces that can embody the features of a Julius Caesar, a Goethe, and a Beethoven all in one, but whose owners, the moment they open their mouths, prove to be the most miserable ninnies under the sun.”

“Fine, a freak of nature,” Hans Castorp said. “And yet not just a freak, not just something to taunt us. For people to be actors, they must have talent, and talent is something that goes beyond stupidity and cleverness, it is itself a value for life. Mynheer Peeperkorn has talent, too, no matter what you may say, and he uses it to put us in his pocket. Set Herr Naphta in the corner of a room and have him deliver a lecture on Gregory the Great and the City of God, something well worth listening to — and in the other corner have Peeperkorn stand there with his strange mouth and a brow raised in great creases and say nothing except, ‘By all means! Permit me to say—settled!’ And you will see people gather around Peeperkorn, down to the last man, and Naphta will be left sitting there alone with his cleverness and his City of God, although he can express himself so clearly that it makes your blood and spit run cold, to use one of Behrens’s phrases.”

“You should be ashamed of yourself, worshiping success like that,” Herr Settembrini chided him. “Mundus vult decipi. I do not demand that people flock around Herr Naphta. He is a dreadful obstructionist. But I would be inclined to stand at his side in the imaginary scene you have just painted with such reprehensible relish. Go ahead and despise distinctions, precision, logic, the coherence of the human word. Go ahead and despise it in favor of some sort of hocus-pocus of insinuation and emotional charlatanry—and the Devil will definitely have you in his—”

Two great recent startup stories (not in Silicon Valley, but both acquired by Google) – part 2 : wiz.io

Reading a few articles about Deepmind (part 1 of this post) and the founders of Adallom and wiz.io, I remembered other stories of European startups or those founded by Europeans. I’m thinking of Spotify (see my posts in 2022 and 2018) or VMWare (see an older post from 2010). We see that more or less curbed ambition has led to different results. Wiz or Spotify have valuations in the tens of billions, Deepmind, Adallom and VMWare (first acquisition) in the hundreds of millions, while the second acquisition of VMWare was also in the tens of billions. I don’t know if there’s a pattern or if I’m creating it artificially, but it’s a bit as if an acquisition in the hundreds of millions was a semi-failure linked to the fear of too much competition or the impossibility of pursuing an independent adventure.

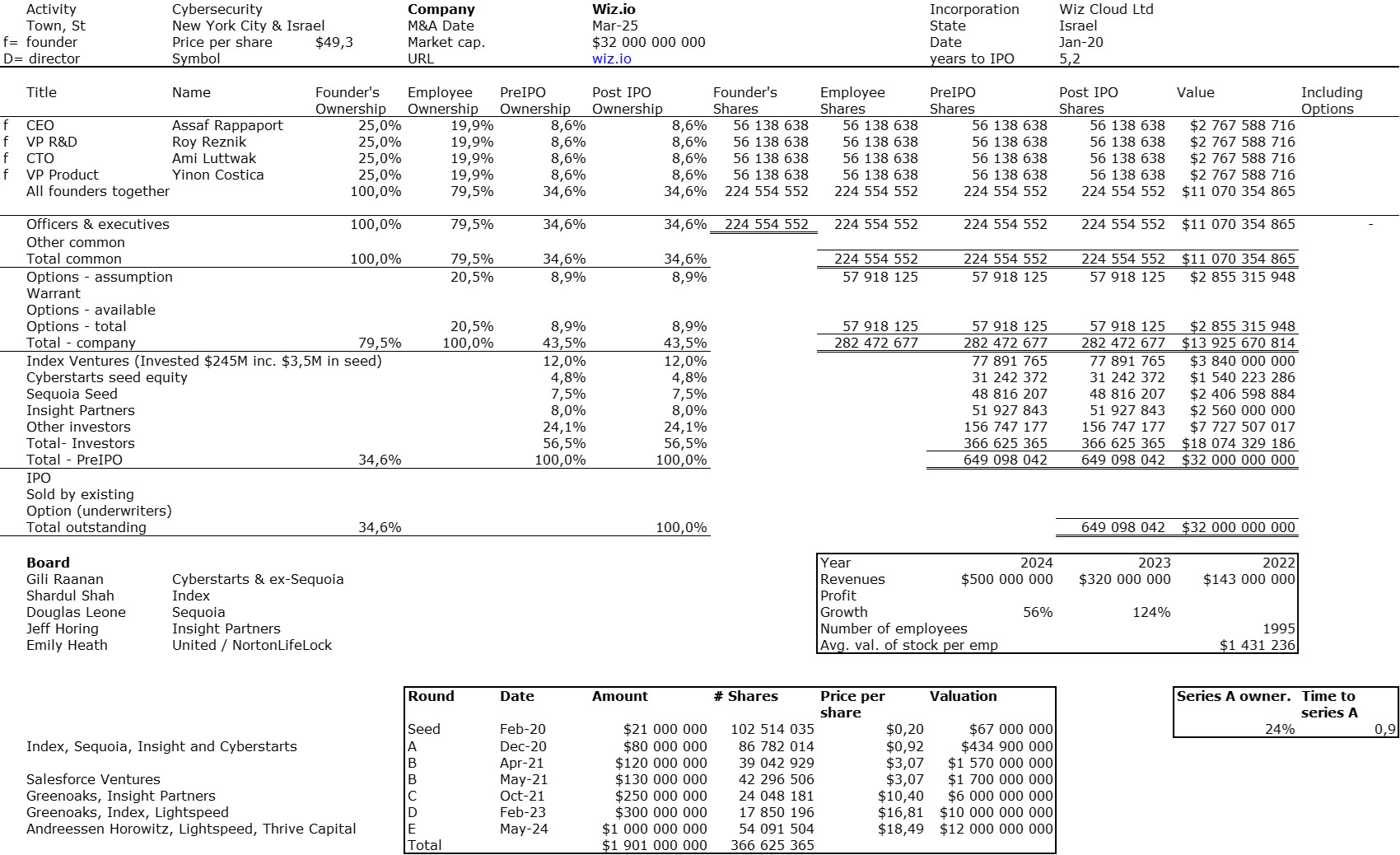

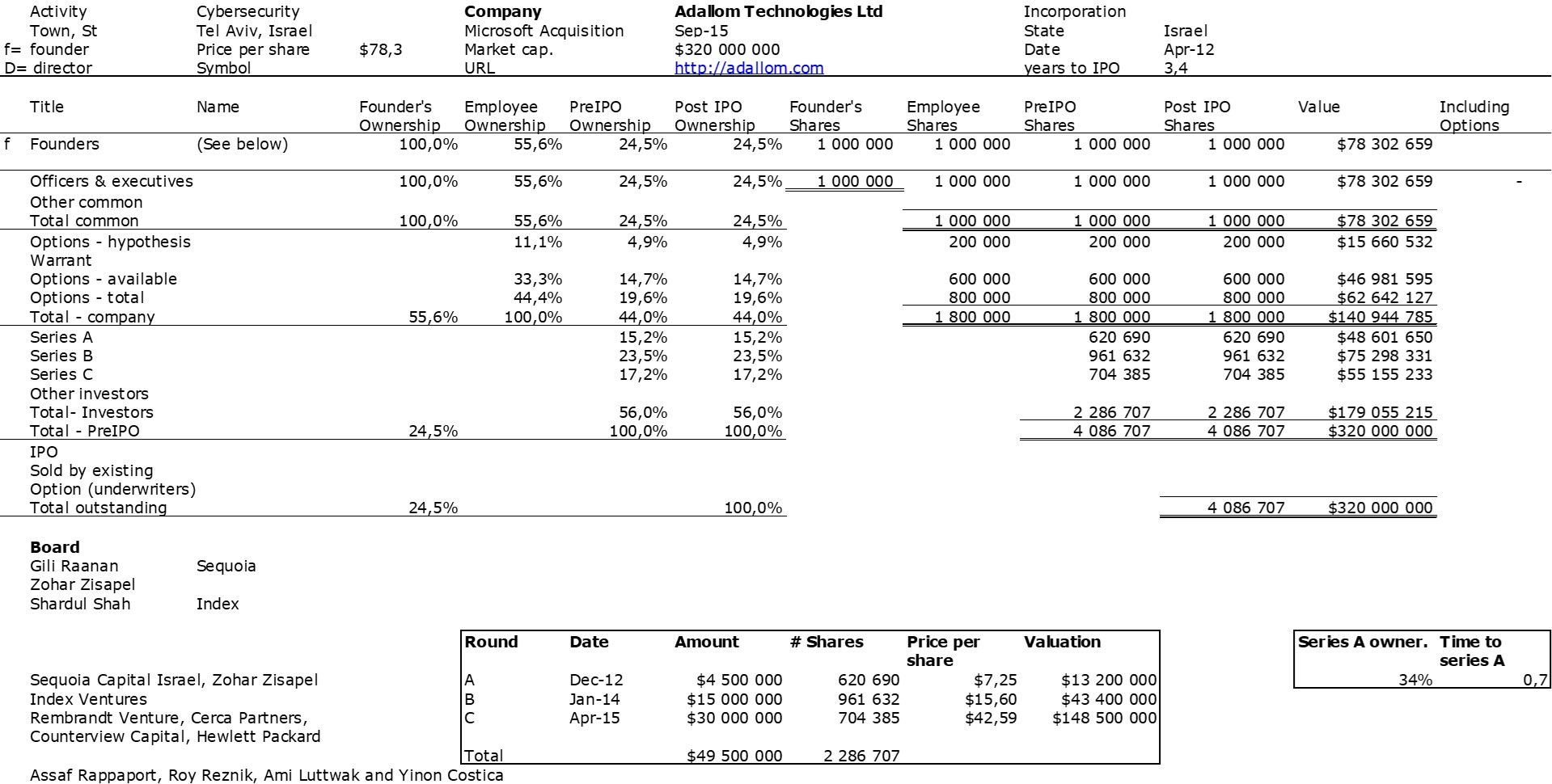

The double adventure of the founders of Adallom and Wiz.io goes a little in that direction. I read a few articles which reference you will find at the end of the article. And I will give the lessons learned by Assaf Rappaport from these two stories. A first success, Adallom bought in 2014 by Microsoft for $320M then a second, wiz.com which Google offered to buy a few days ago for $32B (i.e. 100 times more…) Unlike Deepmind, I did not have access to specific documents, so I had to make some assumptions like some others (see [2]) and cross-check the information available online. Here are the two capitalization tables. But here too, the advice given (which I repeat below) is just as important as this data.

First of all, what I take from the tables:

– Four founders whose story is a classic in Israel (see [1]) created Adallom and then wiz.io. In reality, I am not a big fan of the concept of serial entrepreneurs, but wonder if wiz.io is not rather the scaling up of Adallom like VMWare (2nd period) was for VMware (1st period) or by pushing very hard the Nobel Prize of Demis Hassabis the scaling up of Deepmind! We read in the press that the founders had earned around $25M with Adallom according to some sources and $3B with wiz.io, also a factor of about 100x.

– The same venture capital funds and partners are the investors – Gili Raanan for Sequoia then Cyberstarts and Shardul Shah for Index. These are rare enough to be mentioned especially since these funds intervened at the seed stage.

– For Adallom, multiples of 24x for Series A, 7x for Series B, and approximately 2x for Series C.

– For wiz.io, multiples of 475x for Seed, 73x for Series A, 20x for Series B, 5x, 3x, and 2.7x for Series C, D, and E.

All of this is arguable, but not uninteresting, and there’s a bit of a lottery aspect to it. Don’t get me wrong. Success is rare, never guaranteed. I remember a startup that was offered a $300 million acquisition. The founders and/or investors declined, thinking they were worth more. In the end, the acquisition price was $10 million.

About the ambition and uncertainty, it is also worth reading Shardul Shah (Index) on LinkedIn (Index Ventures just cemented its place as one of the all-time VC greats). Here are some quotes : “I don’t know why we’re talking about averages — none of us are in the business of mean reversion.” […] “I’m not seeking average returns. I’m not seeking good deals—I’m looking for outliers.” […] “I don’t seek comfort. You have to be comfortable with being uncomfortable. We’re in the business of taking risk. I’m not a value investor, right? I believe in the power law.” […] “The hardest thing is identifying if you’re delusional or if you have conviction. Sometimes it can feel like a thin line.”

Finally I extract the lessons from Assaf Rappaport:

1. The team is more important than the idea. A startup is built not around an idea, which is going to change anyway, but around a team. The really good VC funds invest in talent, and not in products, ideas or business plans. And also: Don’t drag your feet when it comes to meeting with the best funds. Don’t leave them till the end.

2. One who listens to problems will find ideas. When you meet with customers, you’re not coming to convince them; rather, you’re there to learn from them. If you’re the one who spoke for more than a quarter of the meeting, it wasn’t a good conversation. Customers have problems that you didn’t even know existed, and the way to discover them is with question marks, not exclamation marks.

And also: You need some luck.

3. ‘No’ is the correct answer to determine whether the investor is serious. No matter what kind of offer you get – investment or acquisition – there’s only one response: ‘I really appreciate your offer, but no thanks.’ This kind of answer never deterred a determined investor or company – and if they’re not determined, they won’t invest in any case. And also: You need to prepare a media plan, both internal and external; when things leak, you’ll have only enough time to hit the Send button.

4. The exit is just the beginning of the hard work. On the day after being merged into a giant corporation, don’t sit back and wait until the options mature. Instead, adopt the commando approach: We’re part of a big army, but we belong to an elite unit.

5. Don’t be afraid of activism. In every company, a moment comes when you have to give the conservative corporate people a kick, and then go ahead and act. To be the best workplace and to recruit the best workers, you need to be brave and take a stand, engaging in social activism that gives rise to tremendous team spirit.

6. Take a deep breath and don’t exhale too soon. You shouldn’t be blinded by big money, instead, use it to quickly acquire paying customers, turn down acquisition offers of hundreds of millions of dollars, and grow the company rapidly so it will become a unicorn.

7. Today, it’s possible to overtake everyone with a computer and Zoom

Once again, risk-taking and limitless ambition.

References :

[1] : 7 lessons from reaching a $1.7 billion valuation in just one year https://www.calcalistech.com/ctech/articles/0,7340,L-3904610,00.html

[2] : WIZ, Esprit, es-tu là? Comment les fondateurs de Wiz refont des miracles après le succès d’Adallom https://trivialfinance.substack.com/p/wiz-esprit-es-tu-la