This is a (very long) summary of “Prophet of Innovation – Joseph Schumpeter and Creative Destruction” by Thomas McCraw, Harvard University Press, 2007. In fact, these are extracts from the book and I mentioned the pages as much as I could. If you are courageous enough to read until the end, you might be interested in buying the full book. Schumpeter is clearly the Prophet of Innovation and Thomas McCraw’s book is a great piece of historical and economic analysis. It is about Schumpeter life, which is by itself interesting. His life was not simple, a devastating first wedding, a personal bankruptcy, a short experience as a minister of finance, the rise of Nazism; stability [nearly?] came at Harvard with a new wedding. But it is first and foremost an amazing synthesis of what innovation and entrepreneurship are about. I could nearly feel a Schumpeterian when I read these clear explanations, despite the fact that Schumpeter was clearly a conservative. So let me try to summarize what I kept from this 700-page book (including 200 pages of notes).

Entrepreneurs are the agents of innovation and creative destruction [page 7]

Schumpeter especially emphasizes the role of new companies in making innovations that interrupt the circular flow. New firms “do not arise out of the old ones but start producing beside them”. In transportation for example, “it is not the owner of stage coaches who builds railways”. Schumpeter also argues that “the entrepreneur is never the risk bearer. The one who gives credit [that is, provides the necessary capital] comes to grief if the undertaking fails. … Even though the entrepreneur may risk his reputation, the direct responsibility of failure never falls on him. [Page 74]

In his definition, the entrepreneur is not a run-of-the-mill business executive, or even the owner of chief executive of a successful firm. The entrepreneur is “the modern type of captain of industry” – obsessively seeking an innovative edge. […] He is not driven solely by a wish to grow rich or by any other “motivation of the hedonist kind”. Instead he or she feels “the dream and will to found a private kingdom. […] There is the joy of creating, of getting things done, or simply of exercising one’s energy and ingenuity. [He] has some characteristics in common with Max Weber’s “charismatic leader”. [Pages 70-71]

The important players in this process are entrepreneurs and investment bankers, who generate “new purchasing power out of nothing”. The investment banker is not just the middleman standing between savers and users of capital; he is instead “a producer” of money and credit, “the capitalist par excellence”. Schumpeter hammered the function of banks in creating money. Keynes had said to him “there were not more than five people in the world who understood monetary theory”, adding that he, Schumpeter, assumed himself to be one of the five. [On note 21, page 533, the author adds “In the history of American capitalism, banks took a smaller role. This did not mean the United States was any less entrepreneurial, of course. It was the most entrepreneurial country on earth, but not because of its banks. Substantial new businesses were funded through “equity” by wealthy families.]

There are 5 types of innovation [page 73]:

(1) The introduction of a new good – or a new quality of a good.

(2) The introduction of a new method of production.

(3) The opening of a new market.

(4) The conquest of a new source of supply of raw-materials or half-manufactured goods.

(5) The carrying out of a new organization.

An important general lesson is that increases in scales almost always require advances in technology which often reduce marginal costs still further. [Note 35, page 525] Steel and automotive industries are just two examples of his time, or more generally steam, electricity, transistors.

Part II begins with an analysis of why entrepreneurship was never widespread even if there were “early forerunners such as Venice, Florence and the Netherlands.” It was even widely resisted for reasons which are “as much cultural and social as they are economic”. (We are talking about an analysis over centuries from the middle ages until the industrial revolution.)

(1) A conviction that spiritual life suffered grievous damage if people became immersed in materialism.

(2) The absence of a belief in upward social and economic mobility.

(3) No widespread sense of personal freedom and individual autonomy.

(4) The governance of most occupations and crafts by cartels (agreements to divide markets and keep prices high) and guilds (exclusive associations of craftspeople).

(5) Entailed estates market by primogeniture. Entailment (imposition of a specified succession of heirs) and primogeniture (inheritance solely by the family’s eldest son) discourage innovation and risk-taking.

(6) A primitive financial system that lacked paper money, stocks, bonds, or any other credit mechanism.

(7) The absence of the two pillars that support all successful business systems: a modern concept of private property and a framework for the rule of laws.

In 1911, Schumpeter flatly asserted that individual entrepreneurship held the key to economic growth in any country. This explains his fascination of the United States but Schumpeter may have missed that it had a strong entrepreneurial spirit from the start. “Capitalism came in the first ships”. [Pages 145-149] The economy has entered the realm of meritocracy, which is inherently hostile to hereditary class. Entrepreneurship had become a function, not a market of class. [Page 159]

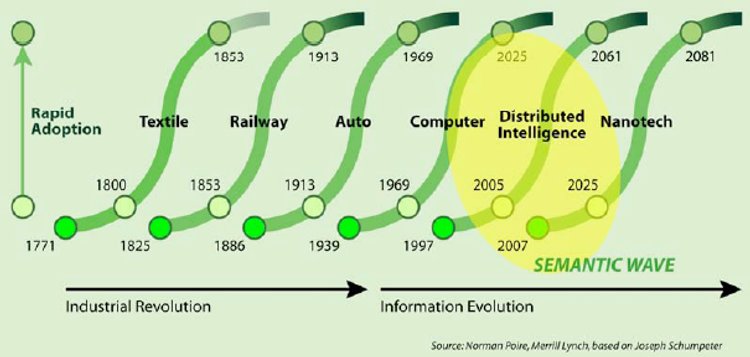

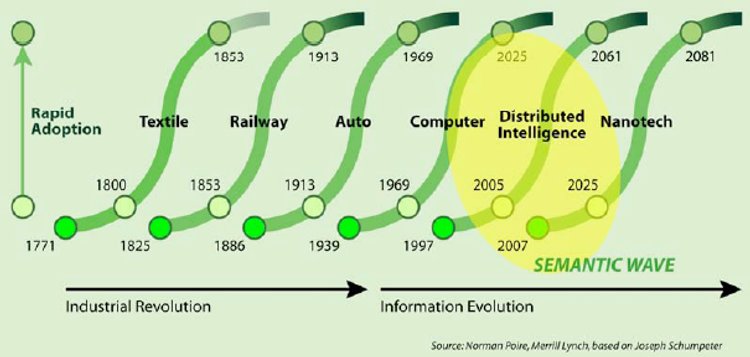

In phase with my quoting Hegel [1] on passion, Schumpeter claims that “no company can ever retain a position at the top of its industry without doing very much more than this – without blazing new trails, without being devoted, heart and soul to the business alone”. Any company [falling into routines] “will soon be overtaken by aggressive, risk-taking competitive entrepreneurs”. “Entrepreneurs need extraordinary physical and nervous energy. The best of them can sustain their efforts on a high level only if they have that special kind of vision – … concentration on business to the exclusion of other interests”. [Page 162] That is why Schumpeter believes in “the Instability of Capitalism”: the whole idea of a capitalist equilibrium is misleading. […] The origins of broad expansions always come from innovations in specific industries, which then ramify into other parts of the economy … such as in textiles, then in steam engines and iron, then in electricity and chemicals. Overall industry-specific innovation does not follow but creates expansion. [Page 163]

He even added that “one cannot assume that capitalism will last forever. No other economic or social system has ever done so, and capitalism may be a transitional phase in a broad movement toward a more egalitarian order. [Note 36 page 566] Outside influences – wars, earthquakes, even many new technologies and inventions – are not the sources of the perpetual changes that characterize capitalism. Instead change is part and parcel of capitalism and it comes from entrepreneurial behavior. [Page 164] Early in the twentieth century, firms such as ATT, GE, Kodak and DuPont set up research departments. They made innovation part of their business routine. At the same time, new firms spring up alongside the giants. […] By definition, innovation causes obsolescence and Schumpeter warns against allowing the old to block the new.

Schumpeter ‘s key point is the insatiable pursuit of success and of the towering premium it pays that drives entrepreneurs and their investors to put so much time, effort and money into some new project whose future is completely uncertain. Financial speculation, though it gets bad press is an important part of the process [page 178]. The entrepreneur tries to preserve his high profit through patents, further innovation, secret processes and advertising – each move an act of aggression [Page 255]. Entrepreneurs reduce cost, then prices, stimulate demand and enable larger volumes. The dynamic process will come many times: “all successful firms have been entrepreneurial at some point, though a given company is certain to be more entrepreneurial at one point and less so at another. When their innovations dwindle, firms begin to die.” [page 181]

Part III – Business cycles – 1939, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy – 1942, History of Economic Analysis – 1954. “Using theory, statistics and history” is a Schumpeter motto, you cannot just do one approach, you need to combine the three to make good analyses.

Business Cycles. Innovation propels the economy. New firms, entrepreneurs drive innovation. All companies must react, adapt. Meanwhile, powerful elements resist major innovations. Nobody ever is an entrepreneur all the time and nobody can ever be only an entrepreneur. The entrepreneur not only innovates but also carries day to day management. The entrepreneur may but need not be the person who furnishes capital. It is leadership rather than ownership. [Again] Risk bearing is no part of the entrepreneurial function. It is the capitalist who bears the risk. [Pages 254-255] A major theme: “the extreme difficulty of changing traditional ways of doing things”. [Page 257]

Schumpeter places heavy emphasis on the role of marketing. It was not enough to produce satisfactory soaps, it was also necessary to induce people to wash. [Page 258] Then he studies cases: textiles (cotton vs. silk) [page 258], rail [page 261], finance [page 264], automobile [page 266], steel [page 267], electricity [page 268]. But McGraw claims book is a relative failure. He apparently got lost into too many details.

Schumpeter also draws sharp distinctions between inventors and entrepreneurs and between inventions and innovations: “The making of an invention and the carrying out of the corresponding Innovation are, economically and sociologically, two entirely different things.” Often the two interact, but they are never the same, and innovations are usually more important than inventions. [page 259] “Necessity may be the mother of invention, but it does not automatically produce innovation” [page 260]. In conclusion of his book, “without innovations, no entrepreneurs; without entrepreneurial achievement, no capitalist returns and no capitalist propulsion. […] Stabilized capitalism is a contradiction in terms.”

In 1942, he published Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. It is interesting to see the connections between Marx, Keynes and Schumpeter. They may disagree, but there was some respect due to the broadness of the vision and ambition. “The book begins with a penetrating and wholly serious fifty-eight-page analysis of Karl Marx’s work. […] Marx was the first economist of top rank to see and teach systematically how economic theory can be turned into historical analysis.” But Schumpeter thinks Marx was wrong because of “his oversimplified view of social classes”, not just capitalists and proletarians, he failed to distinguish the entrepreneur from the capitalist, and the wrong argument that “society’s total income would steadily fall”.

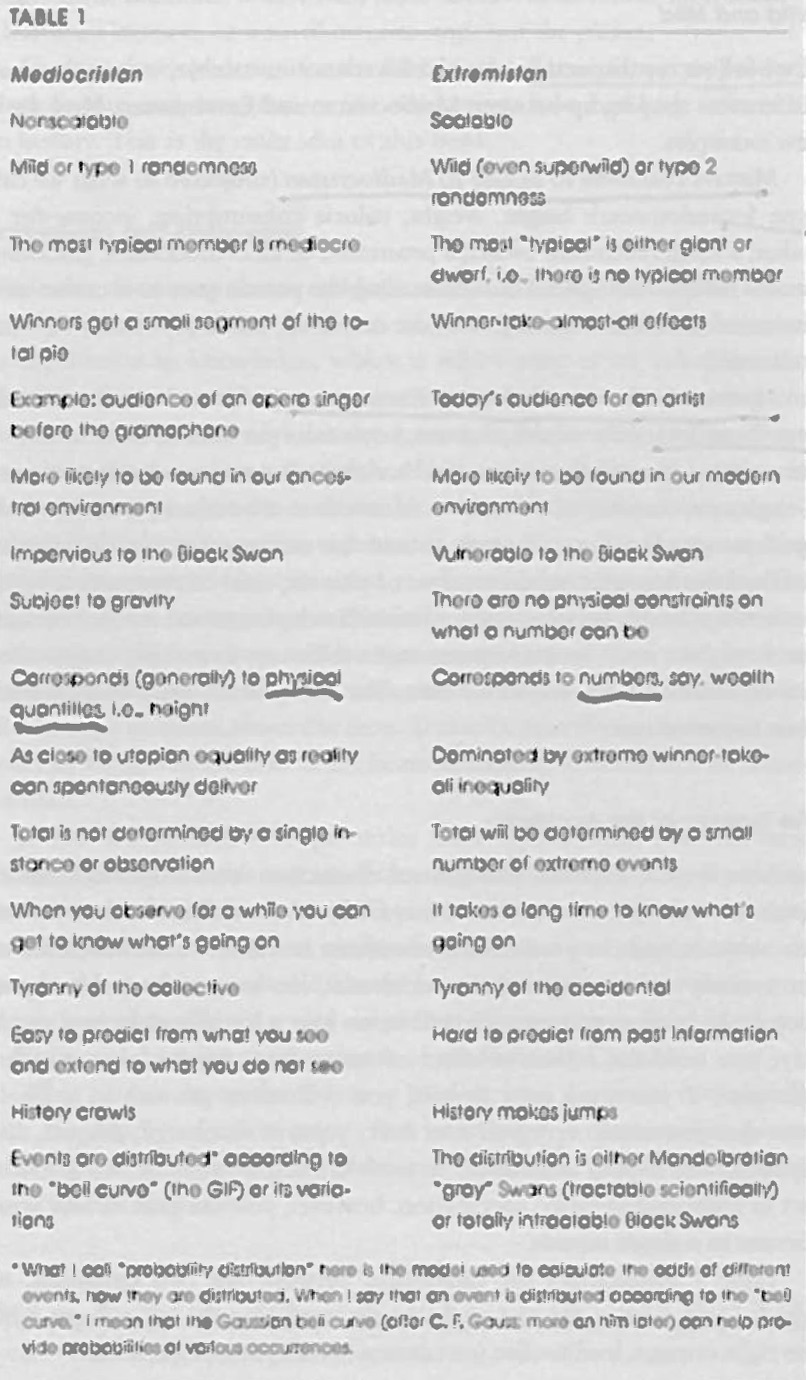

His first question was “Can capitalism survive? No I do not think that it can.” Even if capitalism has produced the greatest per capita output of goods ever recorded, […] in favor of the lower income groups, […] by virtue of its mechanisms […] thanks to businesses of grand size. Then Schumpeter introduces his famous term, “creative destruction”. It is an essential fact of capitalism. It is what capitalism consists in and what every capitalist concern has got to live in. He then criticizes the idea of perfect competition, which does not take business strategy into consideration. There is no perfect information. And there is a continued emergence of new products and new ways of doing things, which is the fundamental impulse that sets and keeps the capitalist engine in motion. Perfect competition and static assumptions are wrong [2]. The economy is about oligopolies, which engage in mass production with very large capital investments. All this does not ease equilibrium analysis or mathematical modeling. [Pages 348-354]

Schumpeter proposes a sharper focus on products and marketing as elements of competition. It is not [that kind of perfect] competition that counts, but the competition from the new commodity, the new technology, the new source of supply, the new type of organization. The economics profession did a capital crime: failing to acknowledge that continuous innovation is endogenous to capitalism. It should focus on change, […] with the mistaken idea that monopoly and big business are the same thing. Long-run cases of monopoly are almost non-existent. Technical innovation and organizational remodeling, not monopolistic profits, account for the prosperity of most great companies. Schumpeter identifies capitalist entrepreneurship with technology progress itself. As a matter of historical record, they were “essentially one and the same thing”, the first being the propelling force of the second.

The tendency of some industries to grow into big business while others do not has seldom been well understood, either today or during Schumpeter’s time. […] The economics literature on why firms grow large is very extensive and often controversial. [Note 55, page 613] Many scholars debated whether Schumpeter believed innovation to be helped or hindered by the rise of big business (see the Economist post – https://www.startup-book.com/2012/01/11/innovation-is-not-about-small-or-large-its-about-fast/ ). Indeed Schumpeter could seem inconsistent. He usually argued that size in and of itself does not preclude innovation, and can promote it in ways that would not occur in small businesses. He did not usually argue that small business was inherently less innovative and he admired entrepreneurial startups throughout his career. A typical misreading: “Schumpeter believed that technological innovations are more likely to be initiated by large rather than small firms” is inaccurate, but plausible! [Note 25, page 639].

His political analysis of capitalism, socialism and democracy may look dated even if it has interesting points. But I see bias as we all have when we talk about convictions or faith… [indeed see below!] Still, let me go on quoting. “Capitalism has developed the seeds of its own destruction. Persons of supernormal ability and ambition can reach a much higher standard of living, provided they would pursue business careers. Capitalism substituted impersonal efficiency to the feudal features. So that people have “the individualistic rope” to hang themselves. The bourgeoisie is politically helpless and unable not only to lead its nation, but even to take care of its particular class interest. Furthermore capitalism and in particular big business undercut not only the aristocracy, but also many small producers and merchants. A share of stock for tangible assets takes the life out of the property. And if this trend goes on long enough, there will be nobody left to defend the bourgeois values” [Page 357].

Large businesses do not command the same degree of loyalty from their workers. Employees take economic progress for granted but they have little emotional attachment to the success of their companies. (And because of the uncertainty), they feel personally insecure. Because people have come to expect a continuous flow of new products and methods, innovation itself is being reduced to routine, progress is depersonalized and automatized. Individual entrepreneurship becomes less salient. By reducing everything to a calculus of costs and benefits, it rationalizes. Economic efficiency is only one of the many human goals and not necessarily the most important to every individual so that the future of capitalism cannot be assured on the basis of is superior economic performance. (And do not forget, there are always cycles and crises…) [Page 358]

His criticism of socialism is also dated, but here it is: a socialist system must replace an economy based on mature big-business capitalism, through routine governmental action and will take 50 to 100 years to complete. The noneconomic attributes need to be primary motives but worth the price of reduced economic efficiency. Can innovation impulses be released as in capitalism this way? Furthermore, it has to be assumed that uncertainties or imperfect information are not an issue, that improvements can be disseminated by a central authority, that business cycles are eliminated, that unemployment does not exist, that the disappearance of the private sphere eliminates friction and antagonism. One way is to nationalize big business while neglecting small producers with a way to motivate managers. (Comment: Schumpeter analyzed Germany, the UK and the USA; not France, which in a way has some attributes of his description). [Page 360]

Then he switches to the analysis of democracy. Schumpeter is not sure of what common good is as it may mean different things for individuals. And it is not the same thing as the choice of the majority. He compares voters and voting to customers and buying, with advertising/marketing as similar. McCraw adds “it is as if he were discussing capitalism in America and democracy in Europe.” “He wrote on democracy as simply a mechanism, while ignoring its powerful ethical dimension.” [Pages 369-71]

[In an over-simplistic manner we can see the old tension between left-weak-collective- equality and right-strong-individual-freedom. In the French motto, I am not sure where we put fraternity.] McCraw quotes Churchill for this chapter: “The inherent vice of capitalism is the unequal sharing of blessings; the inherent vice of socialism is the equal sharing of miseries”. But as a conclusion, imperfect competition is according to Joan Robinson the most brilliant part of the book. (With a background in math, I particularly appreciate Schumpeter’s comment: “There is nothing in my structures that has not a living piece of reality behind it. This is not an advantage in every respect. It makes, for instance, my theories so refractory to mathematical formulation.” Indeed, there may have been far too much math in economy and not enough history…)

The part on World War II shows that the combination of high public investment (military spending) and individual entrepreneurship & large scale business may be the winning recipe, a combination of Keynes and Schumpeter, even if they were academic adversaries… [Pages 383-389]. What makes the book really interesting is indeed noticed by the author himself: “by comparison with other major theorists stretching from Adam Smith to Keynes, he insisted on giving opposing arguments not only their due, but far more.” And this will be confirmed by his History of Economic Analysis published posthumously in 1952.

For Schumpeter, the troubling issue was not economic at all but ideological; widespread prejudice against business, held over from the New Deal. Thus entrepreneurs would have to do their work “in the face of public antagonism, under burdens which eliminate capitalist motivations and make it impossible to accumulate venture capital”. (In these last two words, Schumpeter made early use of a term that became commonplace four decades later. He did not invent the phrase – its origin is obscure – but was one of the first economists to use it.) [Page 424]

The History of Economic Analysis is his grand ‘oeuvre. McCraw quotes Moby Dick’s Melville: “To produce a mighty work, you must choose a mighty theme”. The book “tracks important thinkers down both productive and non productive paths. It shows how potentially seminal ideas often get lost, only to be rediscovered decades or even centuries later.” He also describes bias. “All human beings grow up having subconsciously developed a sense of how the world works. […] All analysis begins with a distinct intuition that is almost inherently ideological, and usually our way of seeing them “can hardly be distinguished from the way in which we wish to see them. This is a dangerous situation for researchers.” […] “The first thing a man will do for his ideals is lie.” [Page 456]

As an example, Schumpeter notes that starting with Adam Smith, the classical economists made use of the term “stationary state” to describe both an existing situation and some condition they thought would materialize in the future, persisting to the stagnationist thesis – the notion that the age of innovation has passed and “mature” capitalism was at hand. And Mill’s ill-advised identification of the entrepreneur with the risk-bearer “only served to push the car still further on the wrong track.” Today in the twenty-first century, many economists add entrepreneurship to the three factors of production as traditionally conceived; land, labor and capital. That addition owes a very great deal to Schumpeter’s own work. [However] entrepreneurship is very difficult to measure and virtually impossible to express mathematically. Gains, returns only emerge when an entrepreneur innovates in some important way – and then disappear as the innovation spreads. Meanwhile they have contributed to general economic growth. The best example is the offering of a new product or a new brand. There are means available to the successful entrepreneurs – patents, strategy and son on for prolonging the life of his monopolistic or quasi-monopolistic position and for rendering it more difficult for competitors to close up on him. By connecting strategy to entrepreneurship in his History, Schumpeter shows that he has come to understand the connection far better than he did before. [Page 458] On the anecdotal side, Schumpeter understands better Keynes: “the arteriosclerotic economy whose opportunities for rejuvenating venture[s] decline while the old habits of saving form in times of plentiful opportunity persist.” Keynes saw the need to invest, Schumpeter the need for innovation. The problem is you need both at the same time.

Schumpeter represents advances in economy reasoning as nonlinear. History of Economic Analysis succeeds where much economic writing of our own time fails, having sacrificed the messy humanity of its subject on the altar of mathematical rigor. Above all else, Schumpeter’s History is an epic analytical narrative. It is about real human beings, moored in their own time, struggling like characters in a novel to resolve difficult problems. [Page 461]. Compared to Keynes, Schumpeter had no reason to think that life was something a person could be expected to enjoy automatically. It was one thing to grow up in Britain – stable, prosperous and ever-victorious – and quite another to be a child of vanquished and vanished Austria. No wonder his vision differed so thoroughly from that of sedentary Keynes as well as those of Smith, Ricardo or Mill. Unlike any of them, Schumpeter had to reinvent himself multiple times. For every episode of destruction, he tried to convert his experience intro a recreation or reinvention of some aspect of economics. [Page 468]

As an intermediate conclusion, again his famous quote in Business Cycles: “Without innovations, no entrepreneurs; without entrepreneurial achievement, no capitalist returns and no capital propulsion. The atmosphere of industrial revolutions – of “progress” – is the only one in which capitalism can survive”

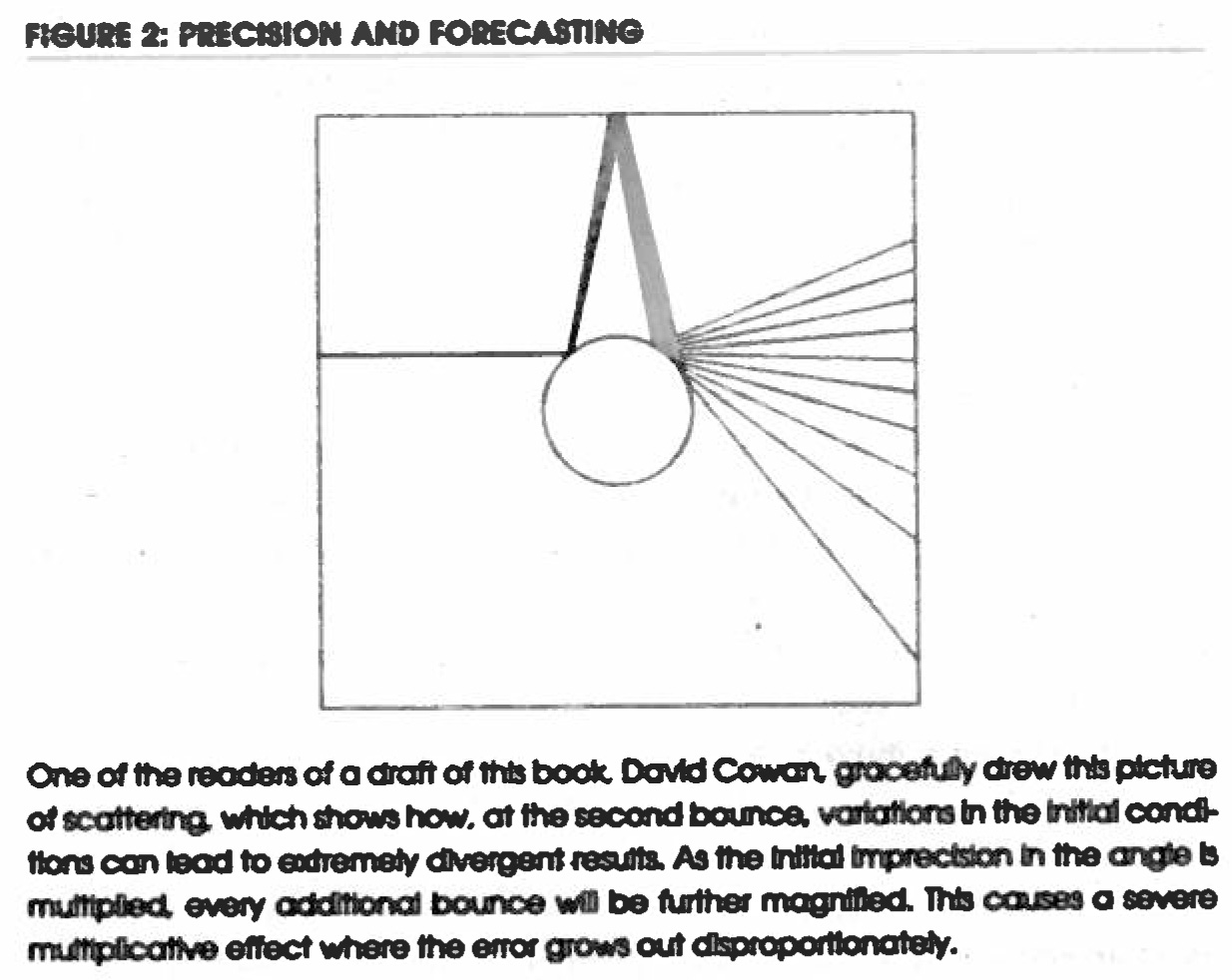

In the last years of his life, he analyzed again what economics is about. The combination of narrative, numbers and theory could exercise a power that none of the three could do alone. Theories are stylized stories; but without real stories and statistics to back them up, they lose much of their force. He also emphasized a “principle of indeterminateness”, contrasting it with Marx economic determinism and one-size-fits-all fiscal Keynesian prescriptions. Time and chance made most economic predictions risky and all determinism futile. Wars and natural disasters disrupted even the most sophisticated forecasts. Equally important for this principle, is the human element of leadership. “Without committing ourselves either to hero worship or to its hardly less absurd opposite, we have got to realize that, since the emergence of exceptional individuals does not lend itself to scientific generalization, there is here an element that, together with the element of random occurrences with which it may be amalgamated, seriously limits our ability to forecast the future.” Schumpeter quest for exact economics had finally ended. [Pages 475-476].

After Schumpeter’s death, comments were many. “Schumpeter’s writings provided an ideal corrective to Keynes’s fatal omission of innovation’s important role in capitalist evolution. Conversely, Schumpeter’s own shortcomings lay exactly in the areas that Keynes’s theories illuminated – where consumption and investment could be considered as aggregates; where analysts could think in macro-economical terms about the total output of national economies.” On entrepreneurship, “his vision of the innovating entrepreneur, who did have glamour and was not dominated by middle-class values, could grow.” [Page 492].

Finally McCraw summarizes Schumpeter contributions:

“Innovation in the form of creative destruction is the driving force not only of capitalism but of material progress in general. Almost all businesses ultimately fail and almost always because they fail to innovate. Only through innovation and entrepreneurship can any business except a government-sponsored monopoly survive over the long term.” Schumpeter finally thought that entrepreneurship could occur within large and medium-sized firms as well as in small ones, despite bureaucratic obstacles. Thus “new men” founding “new firms” were still vital but they were no longer they only agents of innovation. “The history of the information technology industry confirms his thinking especially well – both the scrappy young firms in Silicon Valley that either perished or remained small-to-medium-sized and others that grew to be giants (Hewlett-Packard, Intel, Oracle, Cisco Systems, Amazon [sic], Google, Yahoo). Outside of Silicon Valley, the same pattern obviously holds for Microsoft and Dell Computer, founded by the teenagers Bill Gates in 1975 and Michael Dell in 1984”.

Two other topics were important, the money question and business cycles. “Daily transactions totaling trillions of dollars are driven by intra-corporate repositioning on currencies, by trading in stocks and bonds by funds management. This pattern fits perfectly Schumpeter’s theory of innovation and credit creation as the touchstones of capitalism.” […] “The rise of mixed economies both in industrialized and emerging countries (the major legacy of Keynes) has tended to flatten the business cycles” [Page 499]. He adds on a related note that we may have forgotten the deepness of “the crises in the 1780s, 1810s, 1830s, 1850s, 1870s, 1890s, 1907-08, 1920-21 and of course 1929-39. In 1929, the Dow Jones peaked at 381, in 1932, it was at 41. After the 40s, the business cycles were much smoother and brought under greater control”. Clearly the 2000 Internet crisis and 2008 financial crisis seem to be smoother.

At the same time, in the new world of academic economics, neither the Schumpeterian entrepreneur as an individual nor entrepreneurship as a phenomenon attracts much attention. A focus on the topic would be a quick ticket out of a job. But paradoxically, they’ve been broad enquiries into the nature of innovation. What is it that drives innovation? Several hundred case studies confirm Schumpeter’s thesis. [Page 500] He further adds a long bibliographical note, an opportunity for new readings! I noticed authors I do not know [yet!], such as Frederic Scherer and Mark Perlman [3].

“Schumpeter regarded inequality of opportunity as unacceptable, but he also held that the results produced by inequality of effort were deserved. He found disparity inevitable and effective in stimulating innovation Schumpeter made also a very subtle point: that the benefits to society of important innovations and the lavish profits accruing to winning entrepreneurs must be measured against the total cost of time and money invested in the same industry by unsuccessful entrepreneurs as well. They receive no returns for their efforts, but their competitive pressure spurs the winners to victory – to the great benefit of society. That the winners receive all the rewards is a mere detail – and a temporary one at that, since the “competing-down” element eventually diminishes that profit, as imitators copy the innovation”. [See my post scriptum on bias]

Not until the late twentieth century, long after Schumpeter’s death, did the significance of his emphasis on innovation, entrepreneurship, business strategy, creative destruction, and ample credit as the wellsprings for economic growth become fully clear.

Post-Scriptum: McCraw’s provides also many and interesting comments about Schumpeter views on the academic world: “A scholar’s most creative years came between the ages of twenty and thirty. For this reason, he urged students and colleagues to avoid the distractions of marrying young. Instead, they should concentrate on their work – sifting their brains for fresh ideas.”

About universities [page 416]: “the layman thinks he knows what a professor is. However, this term denotes a group of people who differ widely in type, function, and mentality. There is the academic administrator; the university politician; the teacher in the sense of a man who imparts current knowledge; the teacher in the sense of a man who imparts distinctive doctrines or methods; the scholar in the sense implied by “learnedness”; the organizer of research; the research worker whose strong point I ideas; the research worker whose strong point is skillful technique, experimentation and its counterparts in the social sciences. And all these – and others – are very different chaps and hardly ever fully understand and appreciate one another. Yet it takes all of them to make a modern university and it takes recognition of all these types and the way they cooperate or fail to cooperate in order to understand what a university is and how it works. And he who insists on merging them into a unitary professorial type and leaves it at that will obliterate not only secondary details, but essentials.”

About mathematics: Schumpeter apparently was never at ease with mathematics even if on his own, he performed daily exercises in calculus and tried to master advanced techniques such as matrix algebra. “Whatever the other advantages math may have, it is certainly the purest of human pleasures.” [Page 470]

About scientific bias: During a famous conference in 1948, he accused his fellow professionals in blindness to their own subjective prejudices. In economic analysis, the outcome of “science” depended in large part on the social situation of the individual thinker. “Logic, mathematics, physics and so on deal with experience that is largely invariant to the observer’s social location and practically invariant to historical change: for capitalist and proletarian, a falling stone looks alike. The social sciences do not share this advantage. It is possible, or so it seems, to challenge their findings not only on all the grounds on which the propositions of all sciences may be challenged but also on the additional one that they cannot convey more than a writer’s class affiliations and that, without reference to such class affiliations, there is no room for the categories of true or false. He adds “Model building consists in picking out certain facts rather than others”. [Page 477]

During that conference, he said that Marx was wrong in the increasing misery of the masses, Keynes was wrong on stagnationism and a state of permanent inanition without government stimulus. He criticized the distaste for big business, where only monopolies should be fought. “Schumpeter had come to realize, that like all other analysts, he had his own vision and accompanying ideology. […] What should be done? Nothing! So long as intellectual freedom reigns, one economist’s skewed vision will be balanced by another’s. Ideological vision is a good thing which motivates the scholars to do their work. [Pages 479-483].

About social “sciences”: The relationship of economics to the other social sciences is a complex story. There has been an on-going de-emphasis of courses in economic history in favor of ever more refined mathematical techniques, which have also invaded sister disciplines such as political science, sociology and economic history. After a lifelong struggle, he concluded that exact economics can no more be achieved than exact history, because no human story with a foreordained plot can be anything but fiction. Because of the infinite mixture of influences on human behavior, no two real economic situations are ever exactly alike [Page 504].

Notes: [1] “Passion is considered as something which is not good, which is more or less bad: humankind should not have any passion. But passion is not exactly the right word for what I just designated here. According to me, human activity derives in general from individual interests, from special aims or, if one prefers, from selfish intents. I mean that mankind puts all the energy of its will and of its nature to serve its goals, while sacrificing any other ambition, or rather while sacrificing everything else. […] We shall say therefore that nothing was ever done without being supported by the interest of those who collaborated. This interest, we shall call it passion when, while pushing back all other interests or goals, the entire individuality projects itself on its objective with all the inner fibers of its will and concentrates on this goal with all its strengths and all its needs. With this meaning, we must say that nothing great in this world has ever been accomplished without passion.” Hegel in Reason in History.

[2] Analysis never yields more than a statement about the tendencies present in an observable pattern. And these never tell us what will happen, but what would happen if the continued to act as they have [Note 11 page 636].

[3] Here are some books mentioned by McCraw

– Entrepreneurship, Technological Innovation, and Economic Growth: Studies in the Schumpeterian Tradition (The International Schumpeter Society Series) Frederic M. Scherer (Editor), Mark Perlman (Editor), 1992

– New Perspectives on Economic Growth and Technological Innovation. Frederic M. Scherer, 1999

– The Growth of the Firm: The Legacy of Edith Penrose by Christos Pitelis (with a chapter on Penrose and Joseph Schumpeter on innovation, profits, and growth).