Thiel’s concludes his Class Notes Essays (CS183 —Stanford, Spring 2012) with philosophical considerations about the uniqueness of founders (class 18) and the singularity of technology (class 19). Founders are a topic I regularly covered, for example with European Founders at Work or Founders at Work.

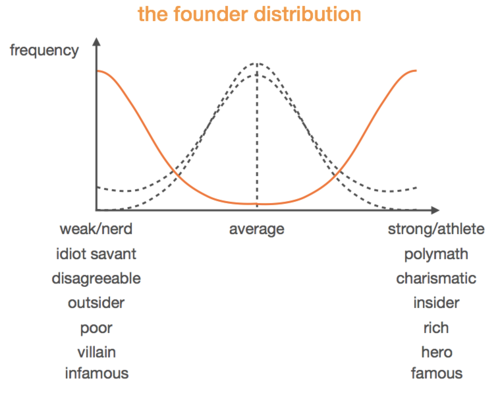

Again Thiel presents unusual ideas about founders. He sees them as a combination of extreme outsiders and extreme insiders.

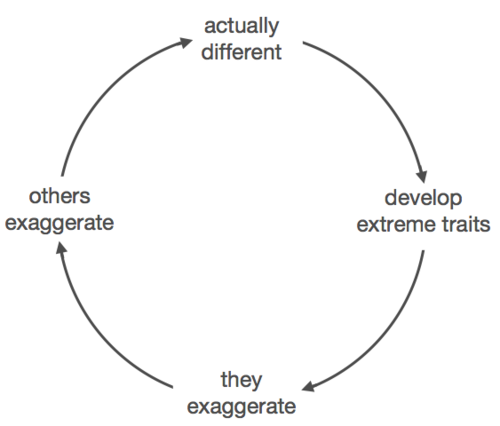

which he reinforces with this virtuous/vicious circle:

If this is not clear, two examples may help:

– “All [these] questions apply to Gates. Was it nature or nurture? He was a Harvard insider but a dropout outsider. He wore big glasses. Did he become a nerd unwillingly? Did he prosper by accentuating his nerdiness? It’s hard to tell.”

– “And then there’s the Steve Jobs version. […] He had all the classic extreme outsider and extreme insider traits. He dropped out of college. He was eccentric and had all these crazy diets. He started out phreaking phones with Steve Wozniak. He took LSD.”

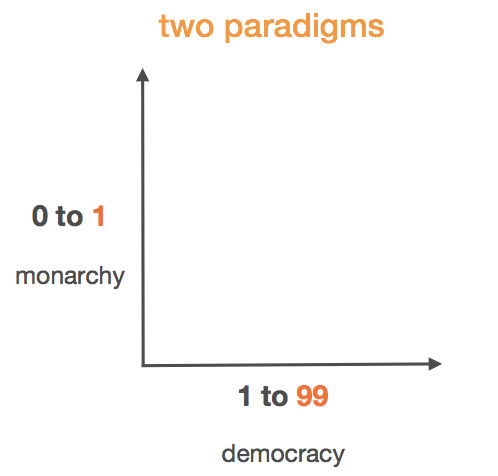

Thiel is convincing when he explains that a start-up is not a democracy. Founders are Kings, and Thiel may have followed René Girard at Stanford since he then develops a theory of scapegoats. The god may become a victim.

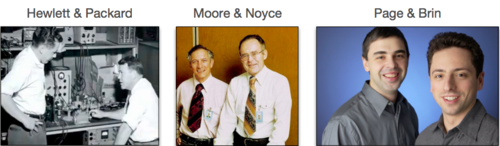

Thiel is a little short about the dual-founder situation: “The dual founder thing is worth mentioning. Co-founders seem to get in a lot less trouble than more unbalanced single founders. Think Hewlett and Packard, Moore and Noyce, and Page and Brin. There are all sorts of theoretical benefits to having multiple founders such as more brainstorming power, collaboration, etc. But the really decisive difference between one founder and more is that with multiple founders, it’s much harder to isolate a scapegoat. Is it Larry Page? Or is it Sergey Brin? It is very hard for a mob-like board to unite against multiple people—and remember, the scapegoat must be singular. The more singular and isolated the founder, the more dangerous the scapegoating phenomenon. For the skeptic who is inclined to spot fiction masquerading as truth, this raises some interesting questions. Are Page and Brin, for instance, really as equal as advertised? Or was it a strategy for safety? We’ll leave those questions unanswered and hardly asked.”

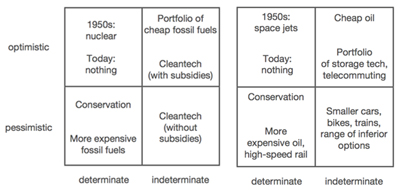

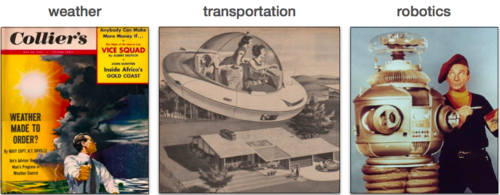

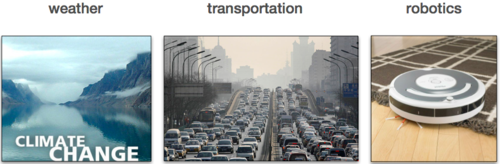

Thiel’s vision (as well as the visions of his guests – I mixed them here) of technology was mentioned in my previous post. Again quite fascinating. “People do tend have some view of the future. They usually project relative stagnation. People tend to believe that, not only will most things not change, but what will change won’t change very quickly.” But “there’s a compelling case that we’ll very likely see extraordinary or accelerated progress in the decades ahead.”

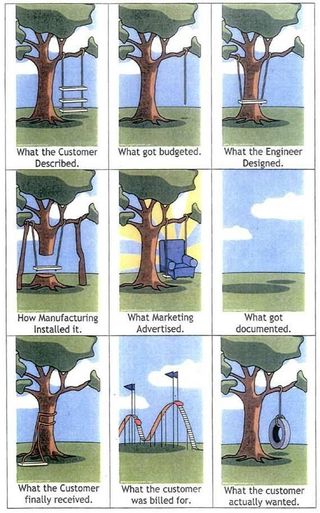

One guest: “My take is that innovation comes from two places: top-down and bottom-up. There’s a huge DIY community. These hobbyists are working in labs they set up in their kitchens and basements. On the other end of the spectrum you have DARPA spending tons of money. Scientists are talking to each other from different countries, collaborating. All this interconnectedness matters. All these interactions in the aggregate will bring the change.

Another guest: “I disagree. There are a very few visionary people who can make a real difference at the formative early stage. This is why mainstream opinion formers are absolutely pivotal. Perhaps no other subset of people could do more to further radical technology. By overpowering public reluctance and influencing the discourse, these people can enable everyone else to build the technology. If we change public thinking, the big benefactors can drive the gears.”

The third guest: “I do not think that progress will come from the top-down or from the bottom-up, really. Individual benefactors who focus on one thing, like Paul Allen, are certainly doing good. But they’re not really pushing on future; they’re more pushing on individual thread in homes that it will make the future come faster. The sense is that these people are not really coordinating with each other. Historically, the big top-down approaches haven’t worked. And the bottom-up approach doesn’t usually work either. It’s the middle that makes change—tribes like the Quakers, the Founding Fathers, or the Royal Society. These effective groups were dozens or small hundreds in size. It’s almost never lone geniuses working solo. And it’s almost never defense departments or big institutions. You need dependency and trust. Those traits cannot exist in one person or amongst thousands.”

Peter Thiel: “That’s three different opinions on who makes the future: a top-down bottom-up combo, social opinion molders, and tribes.”

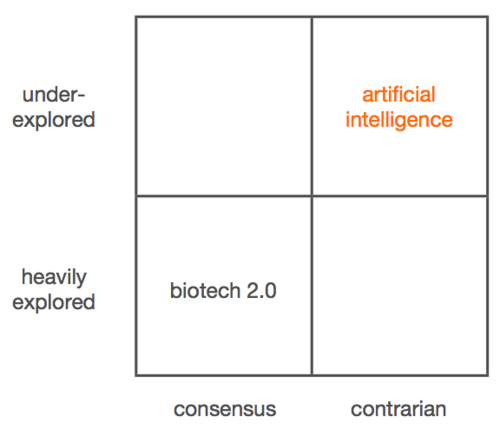

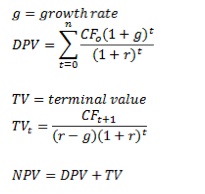

To be honest, I was more convinced with his analysis of founders than of technologies. His conclusion is worth reading as inspiration: “This course has largely been about going from 0 to 1. We’ve talked a lot about how to create new technology, and how radically better technology may build toward singularity. But we can apply the 0 to 1 framework more broadly than that. There is something importantly singular about each new thing in the world. There is a mini singularity whenever you start a company or make a key life decision. In a very real sense, the life of every person is a singularity. The obvious question is what you should do with your singularity. The obvious answer, unfortunately, has been to follow the well-trodden path. You are constantly encouraged to play it safe and be conventional. The future, we are told, is just probabilities and statistics. You are a statistic. But the obvious answer is wrong. That is selling yourself short. Statistical processes, the law of large numbers, and globalization—these things are timeless, probabilistic, and maybe random. But, like technology, your life is a story of one-time events. By their nature, singular events are hard to teach or generalize about. But the big secret is that there are many secrets left to uncover. There are still many large white spaces on the map of human knowledge. You can go discover them. So do it. Get out there and fill in the blank spaces. Every single moment is a possibility to go to these new places and explore them. There is perhaps no specific time that is necessarily right to start your company or start your life. But some times and some moments seem more auspicious than others. Now is such a moment. If we don’t take charge and usher in the future—if you don’t take charge of your life—there is the sense that no one else will. So go find a frontier and go for it. Choose to do something important and different. Don’t be deterred by notions of luck, impossibility, or futility. Use your power to shape your own life and go and do new things.”

Reading these last lines, I remembered the conclusion of my book: “And I suddenly remembered an essay by Wilhelm Reich, the great psychoanalyst, which he wrote in 1945: “Listen, Little Man”. A small essay by the number of pages, a big one in the impact it creates. “I want to tell you something, Little Man; you lost the meaning of what is best inside yourself. You strangled it. You kill it wherever you find it inside others, inside your children, inside your wife, inside your husband, inside your father and inside your mother. You are little and you want to remain little.” The Little Man, it’s you, it’s me. The Little Man is afraid, he only dreams of normality; it is inside all of us. We hide under the umbrella of authority and do not see our freedom anymore. Nothing comes without effort, without risk, without failure sometimes. “You look for happiness, but you prefer security, even at the cost of your spinal cord, even at the cost of your life”.