I remember hesitating to buy Homo Deus. I never really appreciated people trying to analyze what the future might be. I have similar concerns with Harari’s book. I am not the only one as the New Yorker was not all positive: Then he announces his bald thesis: that “once technology enables us to re-engineer human minds, Homo sapiens will disappear, human history will come to an end, and a completely new process will begin, which people like you and me cannot comprehend.” Now, any big book on big ideas will inevitably turn out to have lots of little flaws in argument and detail along the way. No one can master every finicky footnote. As readers, we blow past the details of subjects in which we are inexpert, and don’t care if hominins get confused with hominids or the Jurassic with the Mesozoic. (The in-group readers do, and grouse all the way to the author’s next big advance.) Yet, with Harari’s move from mostly prehistoric cultural history to modern cultural history, even the most complacent reader becomes uneasy encountering historical and empirical claims so coarse, bizarre, or tendentious. […] Harari’s larger contention is that our homocentric creed, devoted to human liberty and happiness, will be destroyed by the approaching post-humanist horizon. Free will and individualism are, he says, illusions. We must reconceive ourselves as mere meat machines running algorithms, soon to be overtaken by metal machines running better ones.

If I feel the same unease, I still beleive Harari asks important questions and he might even have been misunderstood in his real motivation… I link this reading to my recent great readings of Piketty, Fleury and Stiegler.

Whatever some more extracts:

“Because science does not deal with questions of value, it cannot determine whether liberals are right in valuing liberty more than equality, or in valuing the individual more than the collective.” [Page 281]

A strange section is the following: The experiment changed Sally’s life. In the following days, she realised she has been through a ‘near-spiritual experience… what defined the experience was not feeling smarter or learning faster: the thing that made the earth drop out from under my feet was that for the first time in my life, everything in my head had finally shut up… My brain without self-doubt was a revelation. There was suddenly this incredible silence in my head… I hope you can sympathise with me when I tell you that the thing I wanted most acutely for the weeks following my experience was to go back and strap on those electrodes. I also started to have a lot of questions. Who was I apart the angry bitter gnomes that populate my mind and drive me to failure because I’m too scared to try? And where did the voices come from?’

Some of those voices repeat society’s prejudices, some echo our personal history, and some articulate our genetic legacy. [Page 289] Again individual, society and evolution…

We see then that the self too is an imaginary story, just like nations, gods and money. Each of us has a sophisticated system that throws away most of our experiences, keeps only a few choice samples, mixes them up with bits from movies we saw, novels we read, speeches we heard, and from our own daydreams, and weaves out of all that jumble a seemingly coherent story about who I am, where I came from and where I am going. This story tells me what to love, whom to hate and what to do with myself. This story may even cause to sacrifice my life, if that’s what the plot requires. We all gave our genre. Some people live a tragedy, others inhabit a never-ending religious drama, some approach life as if it were an action film, and not a few act as in a comedy. But in the end, they are all just stories.

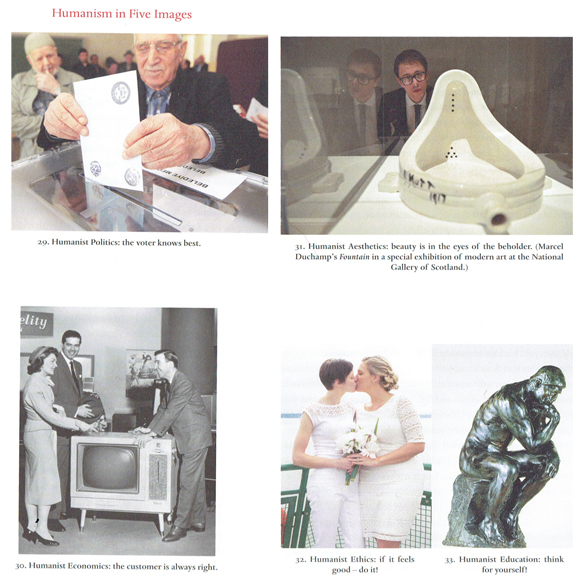

What, then, is the meaning of life? Liberalism maintains that we shouldn’t expect an external entity to provide us with some ready-made meaning. Rather, each individual voter, customer and viewer ought to use his or her free will in order to create meaning not just for his or her life, but for the entire universe.

The life sciences undermine liberalism, arguing that the free individual is just a fictional tale concocted by an assembly of biochemical algorithms. Every moment, the biochemical mechanisms of the brain create a flash of experience, which immediately disappears. The more flashes appear and fade, in quick succession. These momentary experiences do not add up to any enduring essence, The narrating self tries to impose order on this chaos by spinning a never-ending story, in which every such experience has its place, and hence every experience has some lasting meaning. But, as convincing and tempting as it may be, this story is a fiction. [Pages 304-5]

At the beginning of the third millennium, liberalism is threatened not by the philosophical idea that ‘there are no free individuals’ but rather by concrete technologies. We are about to face a flood of extremely useful devices., tools and structures that make no allowance for the free will of individual humans. Can democracy, the free market and human rights survive this flood? [Page 306]

The great decoupling

The practical developments might make this belief [liberalism] obsolete:

1. Humans will lose their economic and military usefulness, hence the economic and political system will stop attaching much value to them.

2. The system will still find value in humans collectively, but not in unique individuals.

3. The system will still find value in some unique individuals, but these will be a new elite of upgraded superhumans rather than the mass of the population. [page 307]

Humans are in danger of losing their value, because intelligence is decoupling from consciousness. [Page 311]

Intelligence is mandatory, but consciousness is optional. [Page 312]

The current scientific answer to this pipe dream can be summarized in three simple principles:

1. Organisms are algorithms. Every animal – including Homo Sapiens – is an assemblage of organic algorithms shaped by natural selection over millions of years of evolution.

2. Algorithmic calculations are not affected by the materials from which you build the calculator. Whether you build an abacus from wood, iron or plastic, two beads plus two beads equal four beads.

3. Hence there is not reason to think that organic algorithms can do things that non-organic algorithms will never be able to replicate or surpass. [Page 319]

As algorithms push humans out of the job market, wealth might become concentrated in the hands of the tiny elite that owns the all-powerful algorithms creating unprecedented social inequality. [Page 323]

Is there too much story telling with Harari’s new book. Is the cashier replaced by a robot, or by the customer? What about the Google flu tool, that is mentioned page 335. Did it really work?

The Ocean of Consciousness

The new religions are unlikely to emerge from the caves of Afghanistan or from the madrasas of the Middle East. Rather, they will emerge from research laboratories. Just as socialism took over the world by promising salvation through steam and electricity, so in the coming decades new techno-religions may conquer the world by promising salvation through algorithms and genes. Despite all the talk of radical Islam and Christian fundamentalism, the most interesting place in the world from a religious perspective is not the Islamic State or the Bible Belt, but Silicon Valley. [Page 351]

The humanist revolution caused modern Western culture to lose faith and interest in superior mental states, and to sanctify the mundane experiences of the average Joe. Modern Western culture is therefore unique in lacking a special class of people who seek to experience extraordinary mental states. It believes anyone attempting to do so is a drug addict, mental patient or charlatan. Consequently, though we have a detailed map of the mental landscape of Harvard psychology students, we know far less about the mental landscape of Native American shamans, Buddhist monks or Sufi mystics. And that is just the Sapiens mind. Fifty thousand years ago, we shared this planet with our Neanderthal cousins. They didn’t launch spaceships, build pyramids or establish empire. They obviously had very different mental abilities, and lacked many of our talents. Nevertheless, they had bigger brains than us Sapiens. What exactly did they do with all those neurons? We have absolutely no idea. But they might well have many mental states that no Sapiens had ever experienced. [Page 356]

Techno-humanism faces an impossible dilemma here. It considers the human will to be the most important thing in the universe, hence it pushes humankind to develop technologies that can control and redesign our will. After all, it’s tempting to gain control over the most important thing in the world. Yet once we have such control, techno-humanism would not know what to do with it, because the sacred human will would become just another designer product. We can never deal with such technologeis as long as we believe that the human will and the human experience are the supreme source of authority and meaning.[Page 366]

The Data Religion

[Dataism] is very attractive. It gives all scientists a common language, builds bridges over academic rifts and easily exports insights across disciplinary borders. Musicologists, political scientists and cell biologists can finally understand each other. […] Dataists are sceptical about human knowledge and wisdom, and prefer to put their trust in Big Data and computer algorithms. [Page 368]

Capitalism won the Cold War because distributed data processing works better than centralised data processing, at least in periods of accelerating technological changes. [Page 372] The Industrial Revolution unfolded slowly enough for politicians and voters to remain one step ahead. […] Technological revolutions now outpace political processes, causing MPs and voters alike to lose control. [See Stiegler again] […] The Internet is a free and lawless zone that erodes state sovereignty, ignores borders, abolishes privacy and poses perhaps the most formidable global security risk. [Here see Beaude] […] The NSA may be spying on your every word, but to judge by the repeated failures of American foreign policy, nobody in Washington knows what to do with all the data. [Page 374]

Dataism is also missionary. Its second commandment is to connect everything to the system, including heretics who don’t want to be connected. And ‘every-thing’ means more than just humans. It means every thing. My body, of course, but also the cars on the street, the refrigerators in the kitchen, the chickens in their coop and the trees in the jungle – all should be connected to the Internet-of-All-Things. […] Conversely, the greatest sin is to block the data flow. What is death, if not a situation when information doesn’t flow? […] Dataism is the first movement since 1789 that created a really novel value: freedom of information [Page 382] which has Harari correctly explains in neither freedom nor freedom of expression.

Humanism thought that experiences occur inside us. Dataists believe that experiences are valueless if they are not shared. Twenty years ago Japanese tourists were a universal laughing stock because they always carried cameras and took pictures of everything in sight. Now everyone is doing it. […] Writing a private diary sounds to many utterly pointless. The new moot says: ‘If you experience something – record it. If you record something – upload it. if you upload something – share it.’ [Page 386] Should I blog?

Dataism is neither liberal nor humanist. It isn’t anti-humanist. [Page 387] By equating the human experience with data patterns, Dataism undermines our main source of authority and meaning, and heralds a tremendous religious revolution. […] ‘Yes God is a product of the human imagination, but human imagination in turn is the product of biochemical algorithms.’ In the eighteenth century, humanism sidelined God by shifting from a deo-centric to a homo-centric world view. In the twenty-first century, Dataism may sideline humans by shifting from a homo-centric to a data-centric view. The Dataist revolution will probably take a few decades, if not a century or two. But then the humanist revolution too did not happen overnight. [Page 389]

A critical examination of the Dataist dogma is likely to be not only the greatest scientific challenge of the twenty-first century, but also the most urgent political and economic project. Scholars in the life sciences and social sciences should ask themselves whether we miss anything when we understand life as data processing and decision-making. Is there perhaps something in the universe that cannot be reduced to data? Suppose non-conscious algorithms could eventually outperform conscious intelligence in all known data-processing tasks – what, if anything, would be lost by replacing conscious intelligence with superior non-conscious algorithms? Of course, even if Dataism is wrong and organisms aren’t just algorithms, it won’t necessarily prevent Dataism from taking over the world. Many previous religions gained enormous popularity and power despite their factual mistakes. If Christianity and communism could do it, why not Dataism? [Page 394]

Humans relinquish authority to the free market, to crowd wisdom and to external algorithms partly because they cannot deal with the deluge of data. [Page 396]

As a conclusion, Harari ends his book with the 3 following questions:

1. Are organisms really just algorithms, and is life really just data processing?

2. What is more valuable – intelligence or consciousness?

3. What will happen to society, politics and daily life when non-conscious but highly intelligent algorithms know us better than we know ourselves?

If reading is not for you, you can still listen to Harari in a recent Ted Talk: Nationalism vs. globalism: the new political divide.