I listened to Xavier Niel on France Culture on December 6th and I had the confirmation of a relatively atypical character. Asked in particular about Elon Musk, here is his answer: Xavier Niel distinguishes between the entrepreneur, “probably the best in the world”, and the character, “completely crazy and potentially dangerous”. He praises his willingness to consider savings for the American state: “if he applies these savings in a reasoned way, to reduce the operating costs of the American state, I am sure that it will go very well. If, after that, we start to overflow, that’s nonsense!”, he qualifies. According to Xavier Niel, it is not so much the fact of paying fot Twitter 45 billion to own the social network that poses a problem, but rather the fact that the product takes on the image of its owner, “which is less exciting”, considers the boss of Free. The price doesn’t shock me if he sets up a plan that will make this company generate money. The purpose of a company is to bring together three parties: employees, customers and shareholders. Consequently, these three parties must be happy. However, the customers are not happy in his case.” In the dialogue he establishes with Jean-Louis Missika, we find a rather fascinating character who uses “ouais” (yeah) and “nan” (nope) as if he were still the kid from Crétail where he grew up. The character is a billionaire but his career has not prevented him from (or perhaps helped him to) staying down to earth unlike some of his counterparts in Silicon Valley.

I liked this book which doesn’t give advice but allows you to understand certain things about his character and his vision of entrepreneurship. A first example: I believe that youthfulness as a state of mind is essential. It is found more often in young people, because when we get older, we become richer, we harden. Youthfulness allows you to create incredible things. You don’t yet have the constraints that are imposed on you when you get older. With age, society imposes limits on you, you no longer have the optimism or the attitude towards risk that you had in youth. Whereas when you are 20 years old, when you leave school, you want to eat the world; you want to do crazy things. [Page 35]

Beyond the usual explanations about this world, Niel expresses unfailing optimism. When I started investing in startups, I was convinced that all entrepreneurs were going to be successful, that they were all going to create huge companies. Well, there were a few disappointments, but you get the idea. In another genre, I thought that Putin was threatening to invade Ukraine but would never act. Just like I thought that Covid would be over in 3 days, and that Brexit would never happen. I am a walking disaster when it comes to forecasts, because I am too optimistic. There are people who use the word “genius” to talk about me; it’s ridiculous, I am absolutely not a genius. I have two strengths, which are based precisely on my lack of intelligence: the simplification of problems, and naivety. […]

JLM: And when it fails?

XN: And when it fails, I forget and move on. Because if you let yourself get discouraged by your failures, or if you listen to everyone who tells you “it’s impossible”, you do nothing. […] When I created Station F, I hoped to welcome 1000 start-ups. And François Hollande, to whom I presented the project, said to me: “But are you sure there are 1000 start-ups in France?” Well, you know what, at the time, I had never asked myself the question! Yet it’s a logical question, I should have thought about it, done a market study, that kind of thing. [Page 39]

The important thing is not the project, it’s the founder. [Page 133]

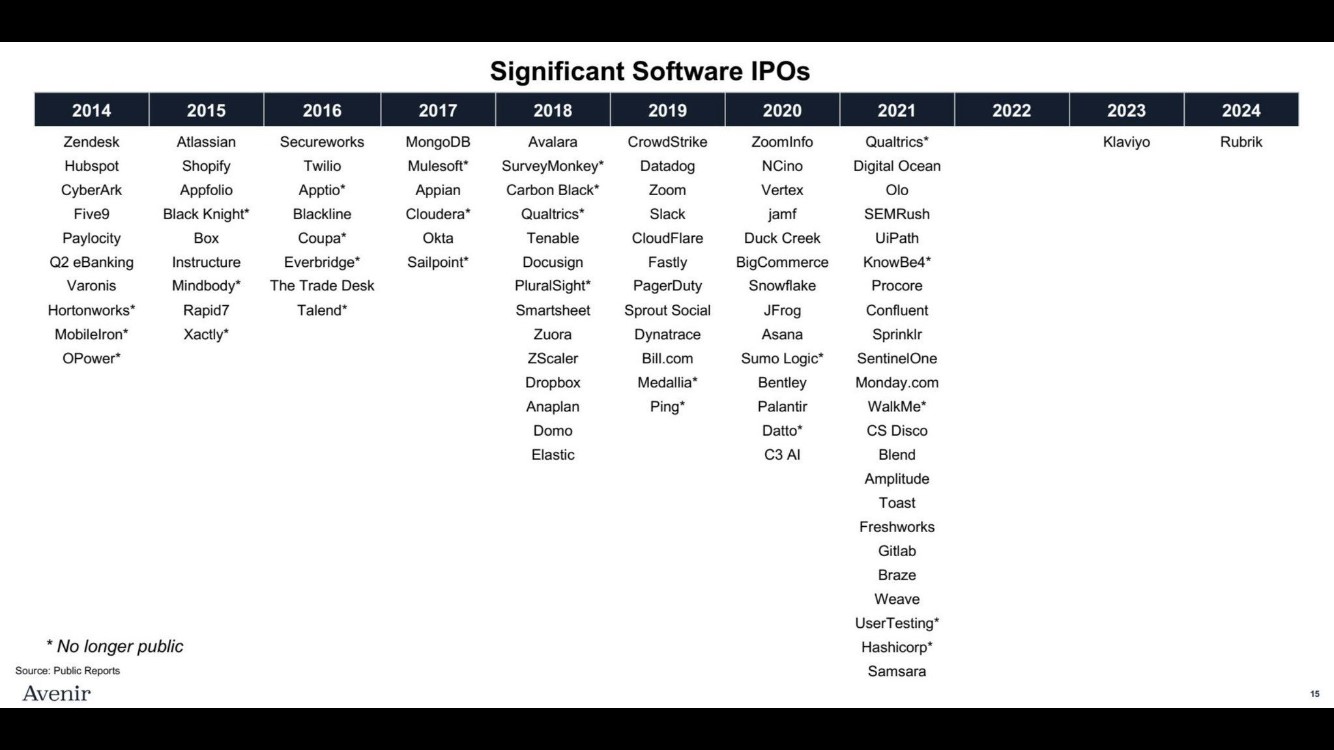

With Kima, yeah, we have a method. We spread the risks. We invest small amounts – around 150,000 euros – in a hundred start-ups each year. Between failures and trade sales, we must have 1,500 participations.

JLM: Less than fifty that work out of 1,500, that’s not a lot…

XN: It’s part of the game. Yes, you’re wrong, and you’re wrong often. […] We don’t finance success, we finance progress. […] Of all my investments, [Square] is the most spectacular performance. I think we did x1,000. […]

The Americans I know who had success with their start-ups were all developers. [Page 139]

Not only did they have the idea for their product, but they also developed their own software, website or app. Google, Facebook, Snapchat, they were all created like that: by people who coded their own products. Hence this idea that a start-up has a better chance of succeeding when there is a coder among its founders. That’s why I created 42.

[whereas] unicorn founders, I love them, but they always have the same faces: three white guys who went to business school [page 145]

Being an entrepreneur is [page 146]

choosing what you do during the day. If you don’t want to make something, you don’t do it. You create your own job. There’s no greater freedom. Is that okay, is that convincing enough?

JLM: Rather. But you’re forgetting the pressure…

XN: That’s not what’s important. What’s important is what you’re capable of creating. […] For me, this desire to create something from an idea, to bring together different people to bring something to society, create value, invent a different product, help the most disadvantaged. Entrepreneurship is an attitude, a state of mind. You don’t need to start a company to be an entrepreneur. Are you launching an association, a project, a social media account with a real editorial line? For me, you’re an entrepreneur. Entrepreneurship isn’t just about business. You can be an entrepreneur in humanitarian, social, educational, environmental, and so on.

A desire for revenge? [Page 204]

The taste for the game is enough in itself. No need for psychology. Everyone likes to play; it’s the playing fields that differ. Mine was the telecom market. Everything is a fucking game. An eternal game, that people have been playing since the beginning of the world. So I play, and whatever the game, I want to win. I want to be first. It’s more or less long, sometimes you get overtaken. And then you catch up. That’s what gives life spice.

[…] When I try to understand why I failed, it’s not because I regret having lost money. It’s because I want to be number one. […] Nope, I just like winning. Money is just a signal that you have won a game, because you are playing with money. [page 205]

Niel is not naive. He is even a fighter. When he returned to Créteil to talk to the “kids” It is not easy to catch their attention. We are mostly white, old, even old fools. So I have a trick to wake them up. I tell them: “I also went to school here in Créteil, and then I went to jail.” And then all of a sudden, the kids wake up. [Page 22] He also admits “Me, since I was little, I wanted to earn money” [page 15] while his first words of the interview are “Frankly, I had the happiest childhood in the world. We were a very close-knit family. I swear, everything was perfect. I was so happy that I thought I was the king of the world, and that my parents hid it from me so that I could have a normal life.”

My closest friends are entrepreneurs, some are Americans, some of whom have created social networks or others are investors. I like entrepreneurs because they are different, because they have a little grain of madness, because I am never bored with them: people see me as a billionaire, but I see myself as an entrepreneur. [Page 222]

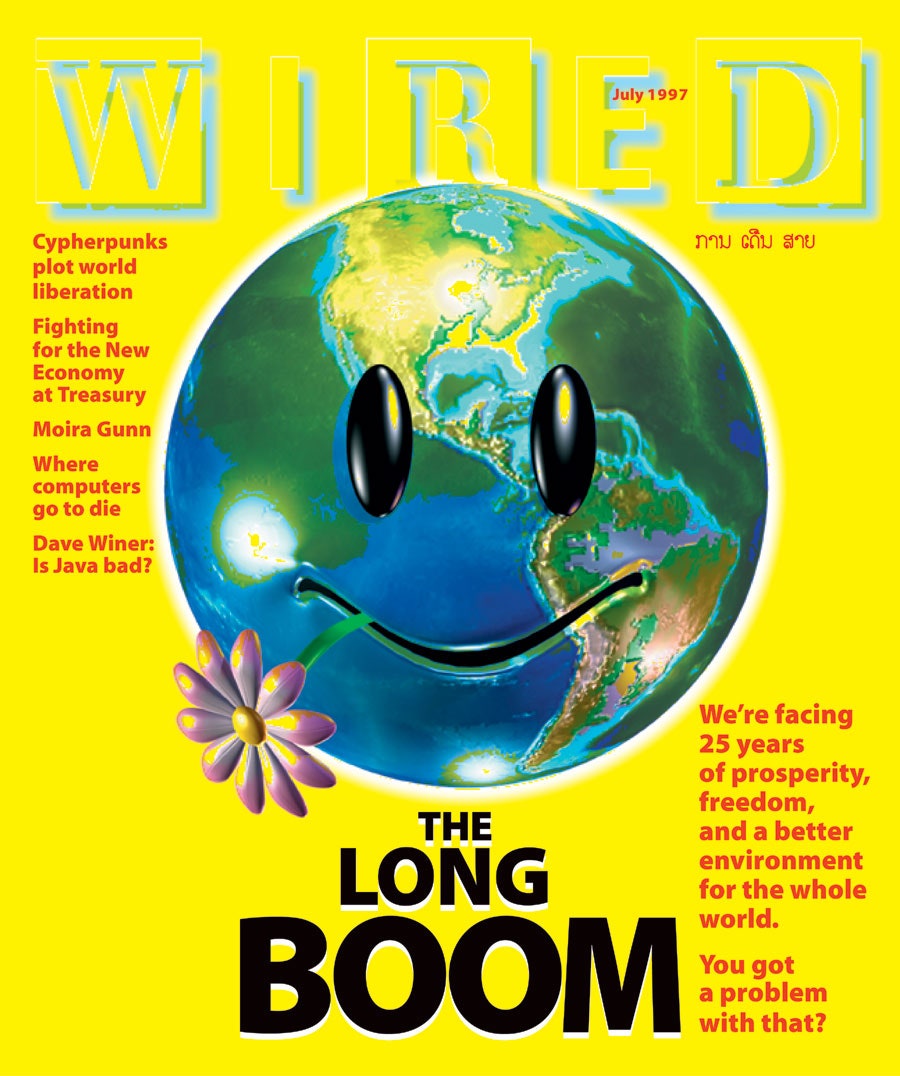

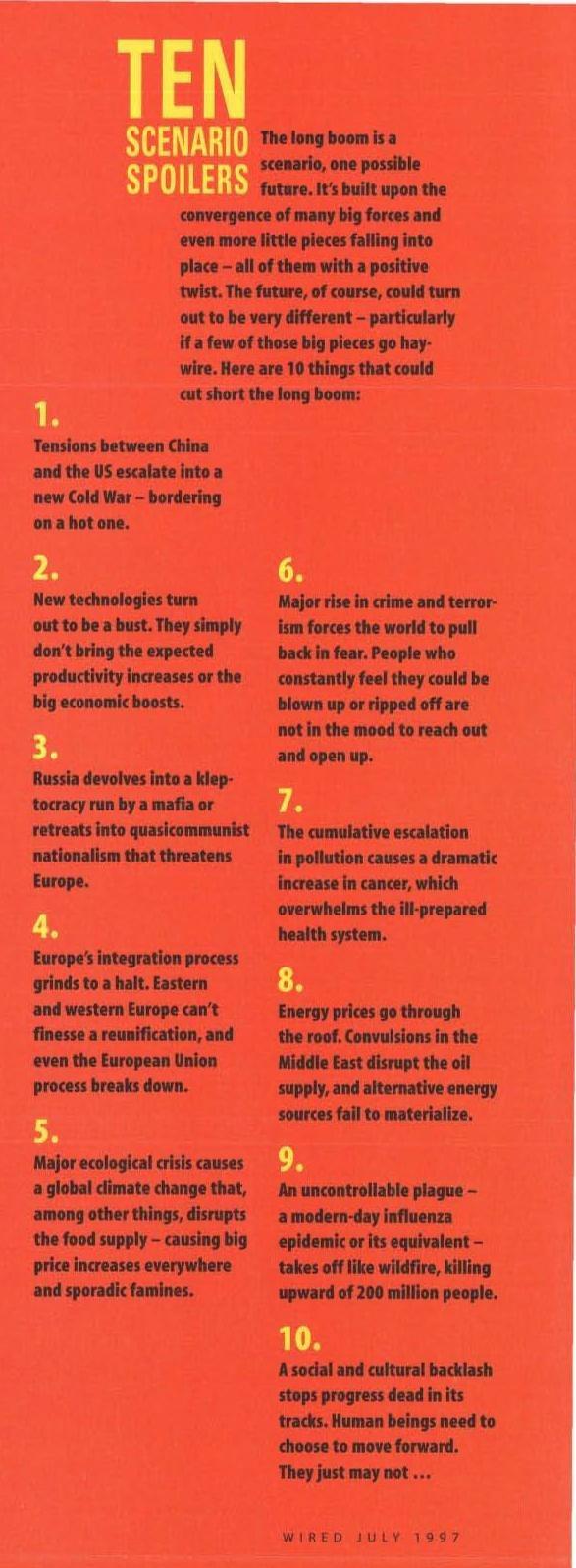

How do you explain the excesses of entrepreneurs? [Page 227]

JLM: When Elon Musk challenges Mark Zuckerberg to an MMA fight, everyone laughs but he ridicules the ecosystem. In a less visible way, the positions taken by Peter Thiel or Marc Andreessen are just as sulphurous, and give the impression of a caste that believes itself above ordinary mortals. You know them a little, how do you explain these excesses?

XN: The people you mentioned are very different from each other. There are some who are a little crazy and who believe they have superior intelligence. And there are others who are a little like children in the playground. It’s… special: But that doesn’t prevent them from having their charm and being interesting. […] But they’re not all like that. And besides, they left Silicon Valley. It’s a part of the ecosystem. Very noisy, yes, but only a part of it.

JLM: We don’t hear the others anymore. They’re nowhere to be seen.

XN: That’s not true, they just do something else. And then if you take the current boss of Google, Sundar Pichai, he’s an Indian immigrant who doesn’t consider himself superior to the rest of humanity. I don’t know his political ideas, but I’m sure they’re quite different from Elon Musk’s. […] Elon Musk only represents himself. He’s locked himself into a transgressive extremist persona and I don’t know how he’s going to get out of it, because by talking bullshit, the time comes when you pay for it. The moral is that you can be both a brilliant entrepreneur and a dirty jerk.

You know when you talk to them, you find yourself in an unreal world, where disruptive innovation is always for tomorrow morning. How many times have I heard that nuclear fusion is in a year. Same for carbon capture. That’s what makes entrepreneurs strong: for them, if you don’t try, you have no chance of succeeding: So they try, again and again. That’s why, despite all their questionable attitudes, I love these people so much.

As a conclusion

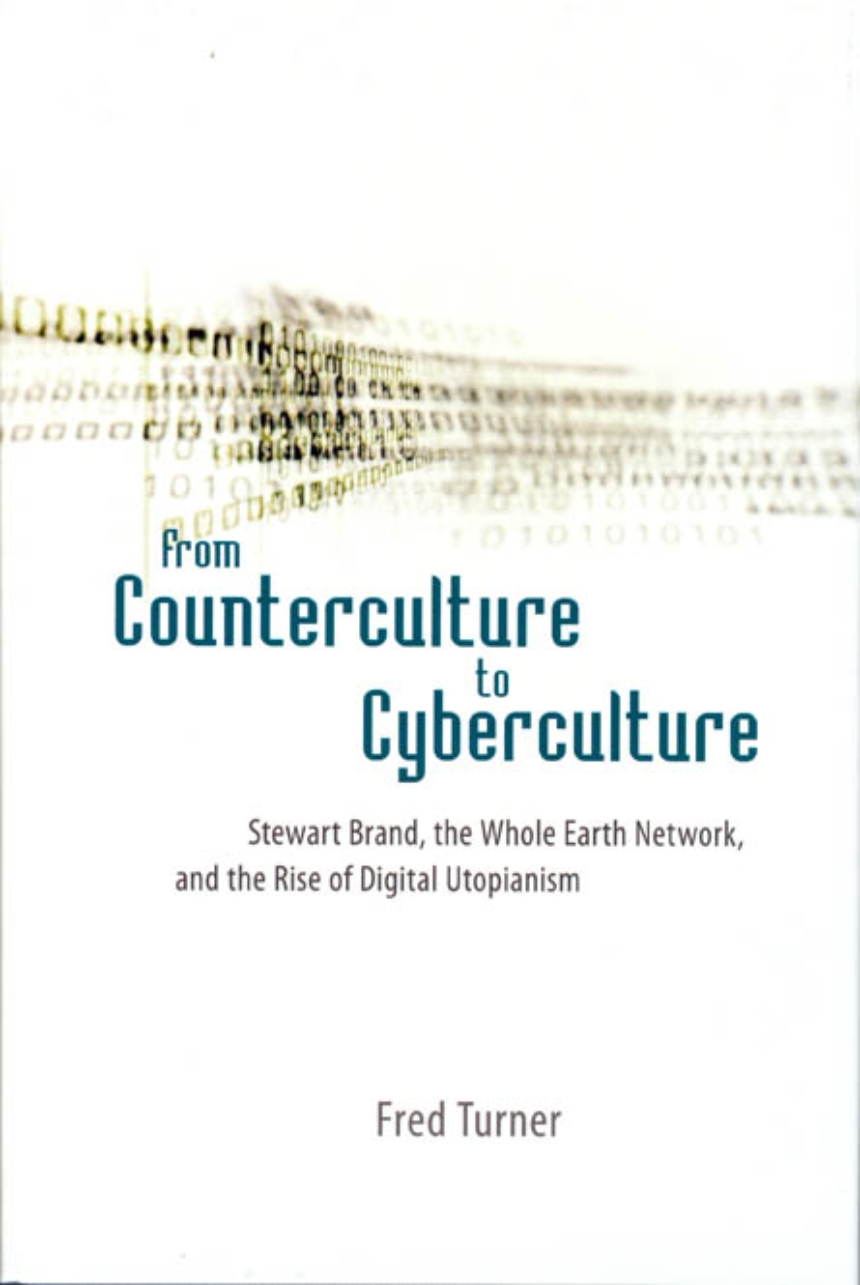

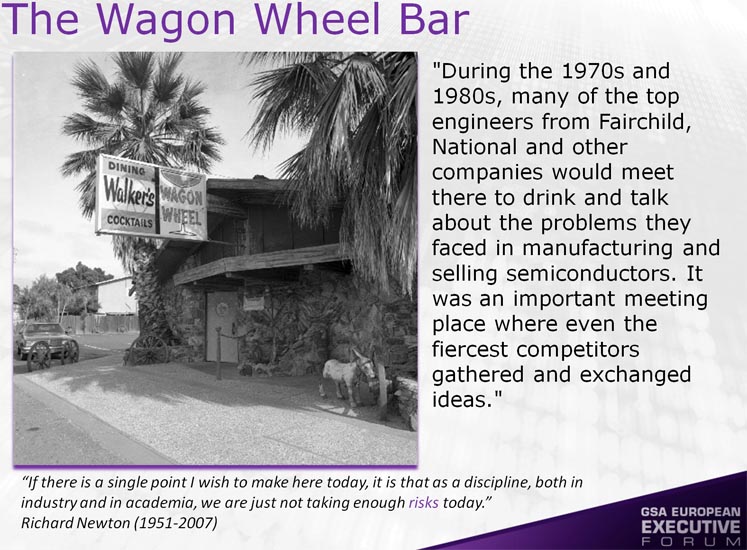

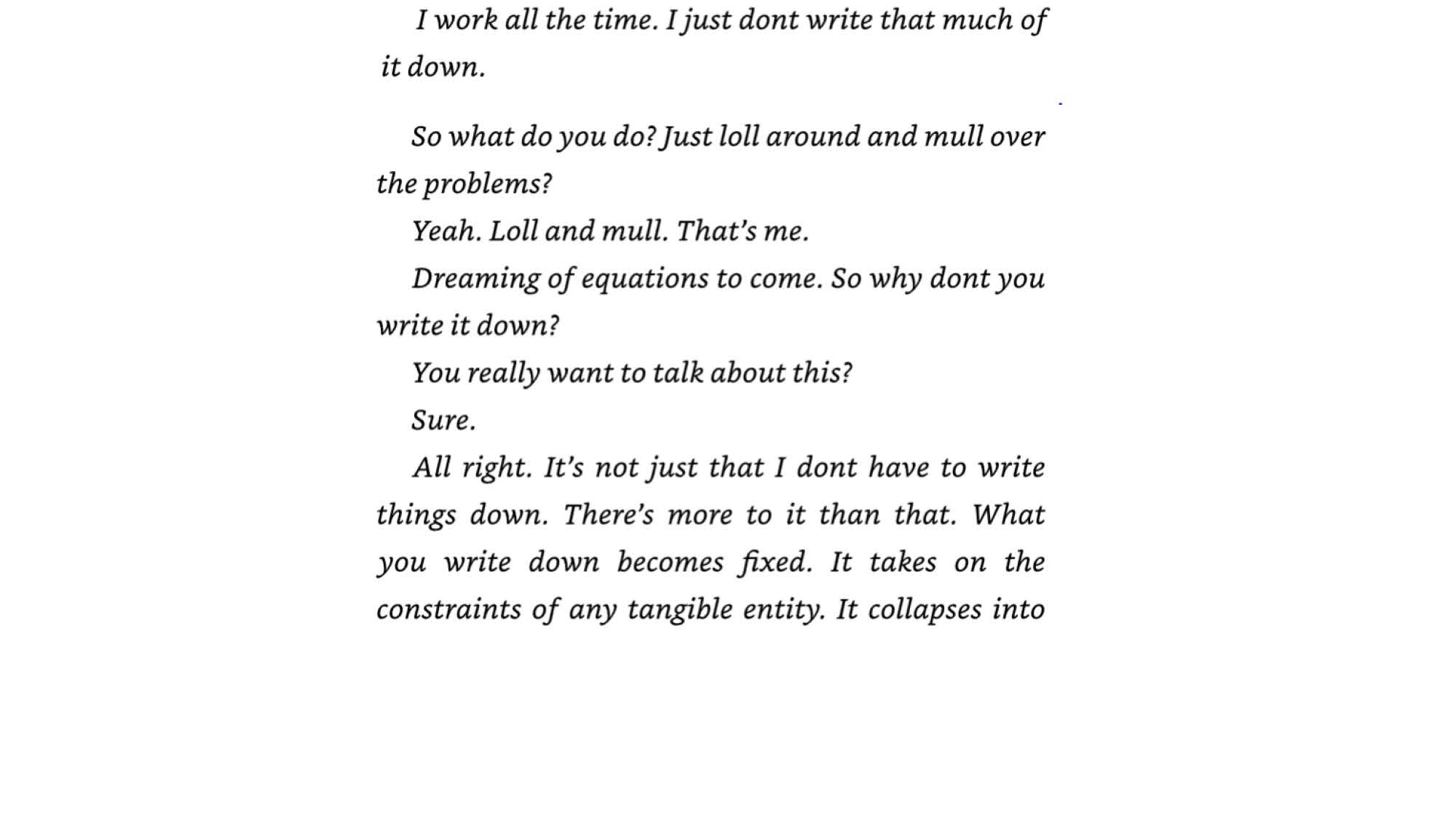

I have already discussed the excesses of Silicon Valley, for example here. Its excesses sadden me and yet, I have a certain fascination for the achievements of its entrepreneurs. This is probably the same reason why I also enjoyed reading Une sacrée envie de foutre le bordel (A real desire to cause trouble). We may not agree at all with Xavier Niel. We may not agree with everything Xavier Niel says. The book is full of exciting anecdotes and also of questionable points of view, we must simply remember that the man is optimistic and defends freedom almost without limits. His limit is the law, and even that… not at the beginning.

I take a step aside. My darling made me discover the beginnings of the MGMT band through an article of FIP MGMT: a magical video of “Kids” in 2003 surfaces

Xavier Niel’s book has a bit of this effect. We often find the child behind the billionaire, his style, his passions. We discover that the entrepreneur is a cataphile. He ventures there about once a month, much more when he was younger…

The last sentence of the book [page 300]: F…!, it’s still indecent, how lucky I was!

PS. For those interested in politics and Silicon Valley, a seminar throughout the first half of 2025 seems to have an enticing program, Digital Capitalism and Ideologies.