The Innovation Illusion: How So Little is Created by So Many Working So Hard by Fredrik Erixon, Bjorn Weigel is a rather strange book but very interesting. I fully agree with most of the authors’ analyses about the illusions we have created around innovation. Less sure I agree with some of their important claims. Their “very liberal” point of view, not to say libertarian, makes their claims sometimes extreme, but in the end, I am not even sure my own claim…

But before beginning, let me mention another interesting piece of analysis from Steve Blank about the innovators. In a recent article in the Harvard Business Review, (The Fatal Flaw That Steve Jobs and Bill Gates Shared), an article that he developed further on his blog, Why Tim Cook is Steve Ballmer and Why He Still Has His Job at Apple, Blank explains how difficult it is to replace a visionary entrepreneur and how they are mostly replaced by executors. I don’t disagree with an answer / analysis on Forbes, Why Apple CEO Tim Cook Is Doing Fine: A Response To Steve Blank’s Critique Of Execution . In a way nobody knows how to innovate in a disruptive manner so the rational decision is to focus on execution.

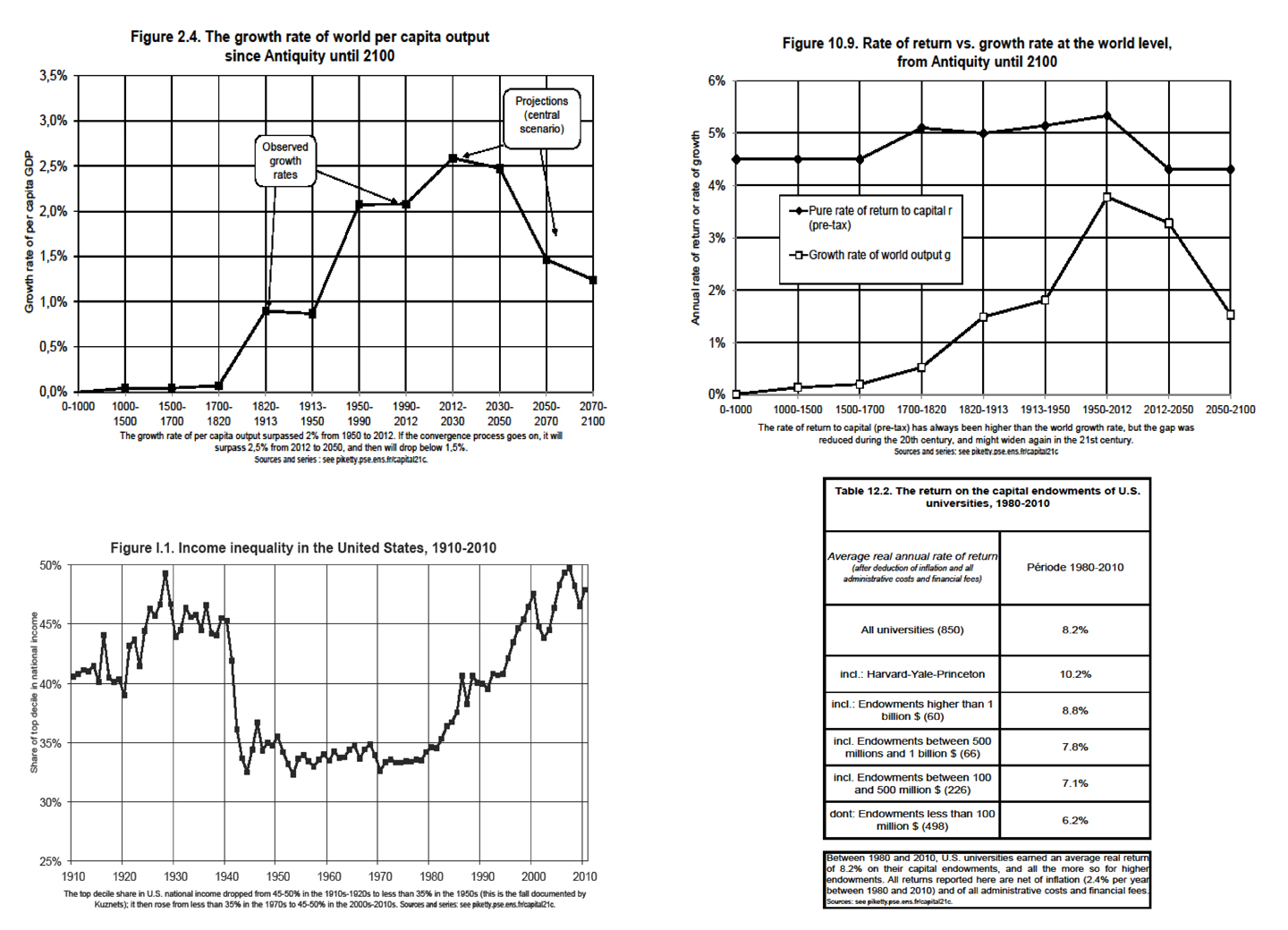

Which brings me back to the Innovation Illusion. My main concern is that the authors claim capitalism has lost its soul, and they explain how, but I am not sure we have answers, in the same way nobody knew how to replace Steve Jobs so that Apple would still innovate… Below, I will quote the authors a lot. I begin first with a brief synthesis of which you will find the elements again later. Basically, the authors could have titled their book Innovation in the XXIst Century (by reference to Piketty’s extraordinary work on capital). Their work probably has the same ambition but may not have had the same means.

– Chapters 3 to 6 describe the reasons why innovation has slowed down, dedicated to capital, managerialism, globalization and regulation respectively.

– Chapter 8 – Capitalism and Robots – is one of the most interesting and I feel much closer to the authors here: “Should we prepare for a technological blitz? The troubling reality is that we should fear an innovation famine rather than an innovation feast.”

– Chapter 9 – The Future and How to Prevent It – is a convincing conclusion, although it is slightly disappointing. Analysis is one thing. The recommendations are much more difficult. I cannot help but feel embarrassed about the main argument that more liberalism will improve the situation. But the richness of the analysis makes this book an unavoidable reading (even if it is demanding …)

Their final recommendation summarize in: “To spark new life in capitalism, attention must be given to, first, severing the link between gray capital and corporate ownership; second, giving competition a real boost; and third, nurturing a culture of dissent and eccentricity.”

Now my usual way of commenting, i.e. by quoting:

[Pages 10-11] In Germany’s DAX30 index of leading companies, only two were founded after 1970. In France’s CAC40 there is only one. In Sweden, 30 of the 50 biggest companies were created before the start of World War I in 1914 and the remaining 20 were founded prior to 1970. If you compile a list of Europe’s 100 most valuable companies, none were actually created in the past 40 years. America is different, but less different from Europe than it used to be.

Their initial analysis [page 16]: The four factors that have made Western capitalism dull and hidebound are gray capital, corporate managerialism, globalization, and complex regulation.

Chapter 2 – When Capitalism became Middle-aged – describes the lack of investment (in innovation) and the slowing GDP growth. The authors show they are different reasons if you look at Italy, France, Germany or the USA.

[Page 29] Take the example of telecommunications. The telecom sector has expanded fast in the past three decades. But for that expansion to happen, companies and governments needed to invest in network infrastructure and other fixed capital – and that is exactly what they did. Likewise, to use these networks, companies and households had to lay out capital expenditures in buying telecommunications equipment like mobile phones and broadband routers. And that is exactly what they did. The telecom example, however, is not representative for entire Western economies. Business investment growth in Western economies is declining and does not follow the pattern you would expect from an economy moving in the direction of rapid innovation fast [productivity] growth.

[Page 33] Moreover, like the rest of society, the concept of “research” in the corporate sector has changed. While the image of corporate research still evokes places like AT&T’s Bell Labs (whose scholars have received eight Nobel Prizes) and Xerox’s Palo Alto research center (PARC), the reality is that a declining share of R&D budgets is spent on research.

[Page 34] Many companies have reacted to problems with their R&D strategy (some of which relate to increasing regulatory costs) by “outsourcing” their R&D to smaller firms that can take bigger risks. Once the R&D investments have begun to mature into innovative products, large companies have acquired them and integrated them into their sales and marketing infrastructure. Pharmaceuticals is one such sector. Time will tell if this strategy works or not. Perhaps it is efficient at the corporate level; perhaps it will destroy the innovation ethos.

[Page 38] Indeed, Studying 15 years of delistings, a group of economists showed that from 1997 to 2012, the US had 8327 delists, of which 4957 were due to mergers. (Cf my own post Cisco’s A&D)

I will not enter into much detail about Chapters 3-6 which describes the reasons why innovation has slowed, chapters dedicated respectively to gray capital, corporate managerialism, globalization, and regulation. Here are some interesting extracts though:

[Page 43] “Capitalists should not be the targets of the angry left or right. People with money and capitalists are not the same thing. […] The tenor of ownership in the capitalist system has changed profoundly, and not for the better. Big capitalists still exist, and some new ones have been minted too, especially in the digital sector. Yet the color of capitalism has turned gray.”

[Page 45] Where market and regulatory trends lead to far greater homogenization of investor behavior, the general profile of corporate ownership gradually comes to reflect broad macro trends and issues around systemic risks rather than the actual merits of a company and its future.

[Page 86] The authors criticize the common negative view about entrepreneurship, i.e. “today we talk about entrepreneurship versus bureaucracy. The entrepreneur represents all beauty in life. It represents progress, optimism and eternal success. The entrepreneur does not need to care about the rest of society. This constant talk about entrepreneurs is dangerous. We can’t afford many of them… The main part of industrial activity and societal maintenance is not built on so-called entrepreneurship.” Or is it?

[Page 89-90] The authors remind us of the difference between risk and uncertainty. Risks can be priced, for instance, just as is done in an insurance contract. […] Uncertainty however is different, in the sense that it cannot be contracted out, neither internally within a firm nor to the market. […] While companies have grown skilled at measuring and handling risks, they have crippled their ability to deal with uncertainty.

[Page 93] Performance tools are great for augmenting operational performance. There is nothing wrong with that aspiration or the tools themselves; all companies can perpetually need to improve, and using best practice is indisputably efficient. But apart from connecting measurements with actual improvements, the platoon of executives graduating from business schools came to believe that the tools were the answer to everything, including how a company should strategize for something new to make money in the future. While the recipe for corporate success cannot be found in a text-book, and not everyone is an entrepreneur just because they have read a book on entrepreneurship, the dominating notion was that strategizing for something new was almost equal to finessing costs by a few percent every year, gradually improving sales tactics, analyzing a key performance ratio here and adding another staffer there, and generally being opportunistic.

(I must quote Blank here again: Over the last decade we assumed that once we found repeatable methodologies to build early stage ventures, entrepreneurship would become a “science,” and anyone could do it. I’m beginning to suspect this assumption may be wrong. It’s not that the tools are wrong. Where I think we have gone wrong is the belief that anyone can use these tools equally well. When page-layout programs came out with the Macintosh in 1984, everyone thought it was going to be the end of graphic artists and designers. “Now everyone can do design,” was the mantra. Users quickly learned how hard it was do design well and again hired professionals. The same thing happened with the first bit-mapped word processors. We didn’t get more or better authors. Instead we ended up with poorly written documents that looked like ransom notes. It may be we can increase the number of founders and entrepreneurial employees, with better tools, more money, and greater education. But it’s more likely that until we truly understand how to teach creativity, their numbers are limited. Not everyone is an artist, after all.”)

[Page 95] To look beyond what is quantifiable from current markets and aim for something new is pretty much the whole idea behind innovation. […] Before penicillin was invented, the market for it did not exist. Before the internet, the market for domain names or web designers was unknown. Before the automobile, who could calculate the return on investment in the car market?

[Page 105] Executive recruiters were not scouting for entrepreneurial people like Elon Musk or Mark Zuckerberg to take up key positions in multinationals. They wanted executives with specialisms in optimization, management, logistics, capital markets, and other key operative functions of a firm. […] And these partners were planners, not entrepreneurs.

[Page 107] Clearly, the era of globalization deserves a central place in future history textbooks. Markets were liberalized. Inflation was brought under control. New forces of productivity were unleashed, lowering the price of goods and raising real income.

[Page 110] Standing behind the fast growth had been, first and foremost, the expansion of emerging markets as sources and destinations of trade, especially China’s move into the global economy. The country’s share of global exports doubled between 1990 and 1996. And then it doubled again between 1996 and 2001, and doubled yet again between in 2001 and 2006. Since 2006, it has grown by just 50 percent. For China and other countries the development was extraordinary. In 2014, China’s GDP per capita was 13 times higher than in 1990, when measured in purchasing power.

[Page 119-121] Second-generation globalization could spur efficiency rather than contestable innovation. […] The patterns of competition emerging under the second-generation globalization period increasingly resembled so-called oligopolistic and monopolistic competition. In a nutshell, globalization enabled concentration and slowed innovation…

[Page 125] A start-up based on a new drug, chemical, battery, turbine technology, or toothbrush for that matter, will have to invest far more today than 20 years ago in order to get into the market and reach scale. It is not just that the price of entry has gone up, but that production is so tightly knitted and efficient that it is difficult to contest the market without stepping into one of the production networks. The more firms have tightened their boundaries, the more they have had to focus on repelling boarders and preventing intruders.

[Page 128-130] Specialized organizations are often better than less specialized organizations at accommodating incremental technological change and the results of investment in research and development with that profile. However, when inventions and discoveries challenge the profile of specialization and the boundaries of the prevailing economic organization, specialization often turns out into a cost. When that happens – as in the case of Nokia and Microsoft – specialization can actually become a factor of resistance to any innovation that disrupts and charts a different future than the one a firm has invested in. […] The high degree of specialization in today’s economy both spurs incremental innovation and slows down radical innovation. […] Technical complexity, social risk management (including lower tolerance for unintended consequences), diminishing returns, and talent challenges have all combined to raise the cost threshold of breakthrough innovation, even as downstream the costs of proliferation – reproducing, replicating, diffusing, disseminating, and indeed hacking innovation – have decreased. Big companies know this by heart. They learnt to navigate this landscape of innovation a long time ago – and thus lost their “Schumpetarian” dispositions.

[Page 146] The flip side of the coin is that the rate of knowledge obsolescence has increased. […] Economist Edwin Mansfield, a scholar of knowledge diffusion, found in a 1985 study of industrial technology that 70 percent of product innovations were known and understood by competitors 12 months after the innovation. That process now works much faster. In later studies, several economists have found the economic lifetime of patents to be much shorter than their duration. [For example…] half of the computer patents are worthless within ten years of their application date.

[Page 149] While there is much that speaks for the narrative of accelerating diffusion, […] the bigger the economic effect of an innovation, the more old capital needs to be retired to make space for the new technology and new capital. With declining levels of investment, the diffusion of new innovation has no necessarily accelerated in the past decade or had a greater economic impact than in the past.

Chapter 7 – Killing Frontier Innovation – claims that the precautionary principle is also killing innovation. The authors give examples about the use of Cadmium & Quantum Dots, about Genetically Modified organisms (GMOs) and their impact on BASF and Monsanto’s strategy, and about coolants in Mercedes Benz cars. It is also true that emerging self-driving cars have created new philosophical debates about “assignments of liability in the events of accidents” [Page 167].

I have to admit that it is a topic where I am not fully convinced by the authors. They give the feeling that innovators and experts should not be blocked by policy makers. With the risk of alienation from society and people… a tough topic. It is true that “uncertainty changes the composition of business investments and expenditure to the disadvantage of R&D and innovation.” [Page169]

But they also acknowledge that “in fact, sometimes innovation can be encouraged by regulation. [..] Take the example of US regulations enacted in the 1970s to lift the environmental standard of automobiles. Several scholars have found that these regulations prompted greater innovation activity among American automobile firms and that they had to shift the allocation of the R&D budget from D to R. […] However [they claim], there are limits to what regulation can achieve. […] Regulation that deters innovation tends to be more frequent in sectors that are important for pushing the technological frontier and that could lift productivity and economic growth” [Pages 170-72].

Chapter 8- Capitalism and Robots – is one of the most interesting one and I feel much closer to the authors here: “Should we prepare for a technological blitz? The troubling reality is that we should fear an innovation famine rather than an innovation feast. The thesis of a New Machine Age radically contradicts our view of stagnating economies, increasingly incapable of catering for their own future. Perhaps we are the old men out, but for us the thesis is a utopian rather than a dystopian vision of the future” [Page 179]. “Undoubtedly, many of the coming innovations in big data, the Internet of Things, machine intelligence, robotics, and more should be commended, yet they fail to impress, at least our technology-frustrated generation. […] We do not get around in flying cars. Nor do we have home fusion reactors. […] New knowledge does not automatically translate into innovation.” [Page 180]

Automation, like previous technological shifts, destroyed jobs, but it also created new ones, and much safer and better-paid jobs at that. […] Contemporary prophets of the New Machine Age make the same mistake. They judge the speed and quality of future innovation on the technological creation they see today, not on how the economy works. […] Intriguingly, they also seem to share the key economic gospels of previous eras of technology: fascination and fear. […] Finally they worry that employment opportunities will be destroyed in the wake of new innovations. […] they ignore two key features about radical innovation. For new technology to power fast-and-furious innovation there has to be, first, entrepreneurship, and second, a general economic dynamism that promotes the contestability of markets. [Page 184]

Innovation comes mainly from its adoption, not from its creation. […] In the example of the global warming, reductions of carbon emissions take longer because of costs and limits in quickly substituting new capital for old. […] Entrepreneurs control their own performance, but they cannot control unpredictable markets; if they could, business failures would be a matter of choice. Innovation based only on its own technological or corporate merits does not have the power to break intro markets. Markets are far too complex for that to happen. [Page 185]

The authors remind us of the recent failure of the Google Glass and also that Ericsson had presented a tablet (the Cordless Web Screen) in 2000. Or the slow evolution of electronic payments since the first plastic cards in 1959. “Tech failures are just one of the problems faced by new innovations. New technologies have to fight for a place in the market. […] The reason is market complexity. […] Think about the infrastructure and how long it took to create that. It is very difficult to change merchant behavior. No one knows how this market will evolve, but markets, competition and consumer behavior – not only the technology itself – will determine its future success. The same is true for another promising technology that can be applied to the payment markets: blockchain. […] Some have billed it as a greater technological leap than the internet for capital markets. Perhaps it will be, but the hype around the technology is premature and the expectation of big market changes is an aspiration.” [Page 187]

Markets are becoming increasingly complex because of vertical and horizontal specialization and a confluence of perpetual trial-and-error processes and generations of technologies, traditions, and customer values. [Page 188]

Don’t get us wrong: the passion of entrepreneurs is exactly why societies should appreciate and encourage them. If they were not, few new companies would make it past their first birthday. Passion is why they sacrifice time with family and friends or neglect private interests and put their money and reputation on the line. […] But the “hockey-stick world” is a fantasy. […] George Foster has analyzed 158,000 early companies and almost two thirds of them experienced one or more consecutive years of decline in the third to fifth year of existence. (Cf “Are Startups Really Jobs Engines?”) […] Markets are difficult to read, let alone manoeuver, even for skilled entrepreneurs. [Pages 189-90]

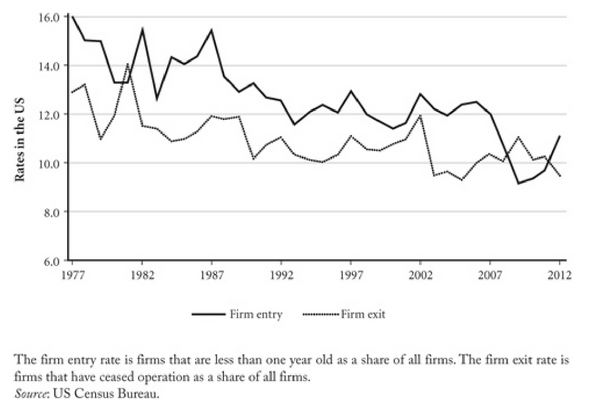

The proportion of firms less than a year old as a share of all firms in the American economy has steadily abated, from a level of approximately 16 percent, to slightly over 10 percent today. […] Only one-third of all firms were 11 or older in 1987, compared to nearly half of all firms in 2012. […] Entrepreneurship is also on an aging trend. […] In 1996, people aged between 20 and 30launched approximately 35 percent of all start-ups in America; in 2014, they only launched 18 percent of them. […] Around 3 percent of all firms qualified as high-growth companies in 1994-97, but in 2008-11 that share had been cut by half. True the latter period came amid a crisis-recovery cycle and it may be that declining business dynamism followed on the heels of the general downturn. However, that is not the lesson from history: crises, for sure tend to hit output and corporate size, but they also create good opportunities for new firms with the capacity to grow. [Pages 191-2]

And the authors go much further [Pages 195-6]: There is even more conclusive evidence against the hypothesis of discriminate dynamism. Investment in ICT equipment when measured as a share of GDP has been on the decline since the beginning of the millennium. […] Big claims require big evidence. And should make people doubt rather than accept the promise of fast-and-furious innovation is that it is thin in actual confirmation. […] The argument comes in three different instalments. First […] cyclical effects have hidden the structural shifts taking place in the Western economy. Second, there is a growing disconnect between recorded data and the real improvements. […] Third the decoupling of productivity and labor incomes prove the transformational change of technology.

But the authors dismiss the arguments. [Page 196-8] The cyclical effects have substantially weakened over time to become acyclical. Technology optimists like Brynjolfsson and McAfee would disagree, but [their] propositions do not stand up scrutiny. The second argument is more intriguing. But the problem of measuring innovation was settled a long time ago. The real debate should be about whether the problem has increased or decreased over time. […] Unfortunately, those who make the claim about the growing mismeasurement of innovation do not have much conclusive evidence supporting their thesis. […] The productivity slowdown has been universal for Western economies and it shows next to no variation when compared to ICT intensity in the economy. […] Moreover, if it were true that recorded economic output was significantly below the actual value, there would be at least one sector where that relationship did not hold – the sector that produces and services all the digital hardware and software. It is difficult to find evidence supporting that view. The growth in revenues and productivity is simply too small to account even a fraction of the mismeasurement.

[Page 201] Like so much else in the gospel of the New Machine Age, the criticism about productivity, real GDP and consumer surplus fails to appreciate other periods in history than our current time. It is as if the period of innovation is a recent phenomenon, something that merged via the internet.

Here a side comment, of interest only for those interested in start-up valuation, [page 200]: Such valuations rather reflect smart structures of financing. Equity investors are in the business of buying and selling company shares. And the price of a share is the result of both internal and external factors – such as capital market trends, regulatory frameworks, and substitute goods. To safeguard investments from the changing dynamics of markets, investors naturally protect themselves. Later investors (referring to investment stages) routinely use liquidation preferences to guarantee returns even if future liquidation valuations disappoint. Layers upon layers of liquidation preferences are virtually the norm and it helps drive private company valuation by allowing for investors to accept higher valuations. If expectations are not met, investors are still protected and get their money back before founders and employers. And it all looks good from the outside; it shows business strength and attracts employees, customers, partners and new investors. But many times it is a house of cards.

Technology and income – are they decoupling? Even there, the authors disagree with authors such as William Galston, Martin Ford or Brynjolfsson and McAfee again [page 202] adding there seems to be growing support for the proposition that productivity growth destroys jobs. [But] the thrust of serious analysis suggests that productivity growth does not decrease demand for labor and that the relationship between productivity and unemployment is trivial. Productivity growth, however, changes the composition of labor. Naturally, productivity growth and innovation can lead to capital substituting for labor, and it is generally acknowledged that economies have technological unemployment. […] but about the decoupling story: is that thesis more convincing? No, is the simple answer.

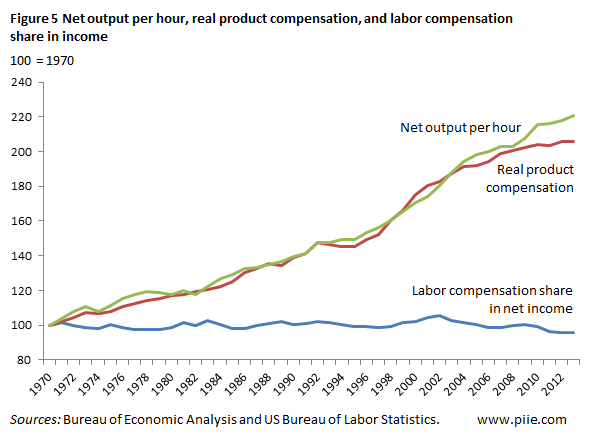

“Harvard economist Robert Lawrence has measured net output per hour and adjusted compensation with the same deflator, to allow for comparison over time, and comes to a sobering conclusion for the United States. All things taken together, the gap between productivity and compensation growth between 1970 and 2000 generally does support the thesis of a dramatic decoupling”. [Page 205]

But the authors again show the complexity of the causes, in Germany, in the USA, in the UK, in Sweden. “Three sectors explain about two-thirds of the falling share of labor income in the US manufacturing sector, and in all three sectors new technology tends to augment labor rather than capital. In other words, the marginal output of labor has gone up faster than the marginal product of capital.” [Page 206] In Sweden, “While income inequality has accelerated rapidly, the real cost of labor closely follows productivity.” [Page 207]

What is dramatic however is the long-term effect of lower productivity growth. White House economists, comparing various effects on pay from different sources of growth, suggest that if productivity growth between 1973 and 2013 had been the same as productivity growth prior to 1973, incomes would have been 58 percent (or 30,000) higher in the United States. By contrast, if income equality has stayed the same, incomes today would “only” be 18 percent (or $9,000) higher. [Page 207]

And what about the Foxconn legend! “In 2011 its Chief Executive Officer, Terry Gou, announced it was aiming for 1 million robots. […] Its 1.2 million workers assemble products for Apple, Sony, Nokia, Motorola, and others. The example of Foxconn became the smoking gun for believers in the New Machine Age. […] In early 2015, Gou was still on the offensive, claiming that 70 percent of assembly-line work would be automated within three years. […] later Gou’s story changed. In fact, after his bold announcement, Foxconn had not installed more than 50,000 “automated employees” well into 2015. That summer, Gou suddenly retracted his claim and blamed the media for having misunderstood the original announcement. Robots, he now claimed, would substitute for only 30 percent of Foxconn’s manpower – and it would happen in five, not three years. […] the jury is still out on Foxconn, but the chronicle of its robotization is revealing. [Pages 209-10]

And the authors add, “it is not technology we should worry about, but economic behavior determined or aided by regulatory uncertainty and corporate leaders whose lives are too focused on rentier returns.” [Page 214]

Chapter 9 – the Future and How to Prevent It – is a convincing even if slightly disappointing conclusion. Analysis is one thing. Recommendations are much more challenging. They convincingly use the BRIC acronym for a Bloody Ridiculous Investment Concept. They focus a lot on regulations as a critical blocking point. Regulatory uncertainty has three main sources: political leaders have become a very anxious species, occupied as much with the Twitter reaction to policy as with the quality of the policy itself. Second. Regulation has become much more prescriptive and less proscriptive.

As of their final recommendations:

– Severing the link between gray capital and corporate ownership

First action is needed to prevent investment institutions from draining companies of capital. […] One way to sever the link is to grant companies greater freedom to discriminate between owners by expanding the usage of dual class stock. […] Both google and Facebook have dual share structures, something that arguably helped to maintain a culture of innovation in those firms. A few days after Facebook’s initial public offering, founder mark Zuckerberg owned 18 percent of Facebook, but controlled 57 percent of the share-votes. The reason is obvious: maintaining entrepreneurial spirit. [Page 233]

– Boosting the contestability of markets

Greater competition should also help to speed up the exit of low productivity firms. […] In the US, for instance, there is greater variation in pay between firms than within firms. […] Related to that, market regulation has generally skewed the market, favoring older firms over new, leading to more consolidation of markets and higher entry barriers. [Page 235]

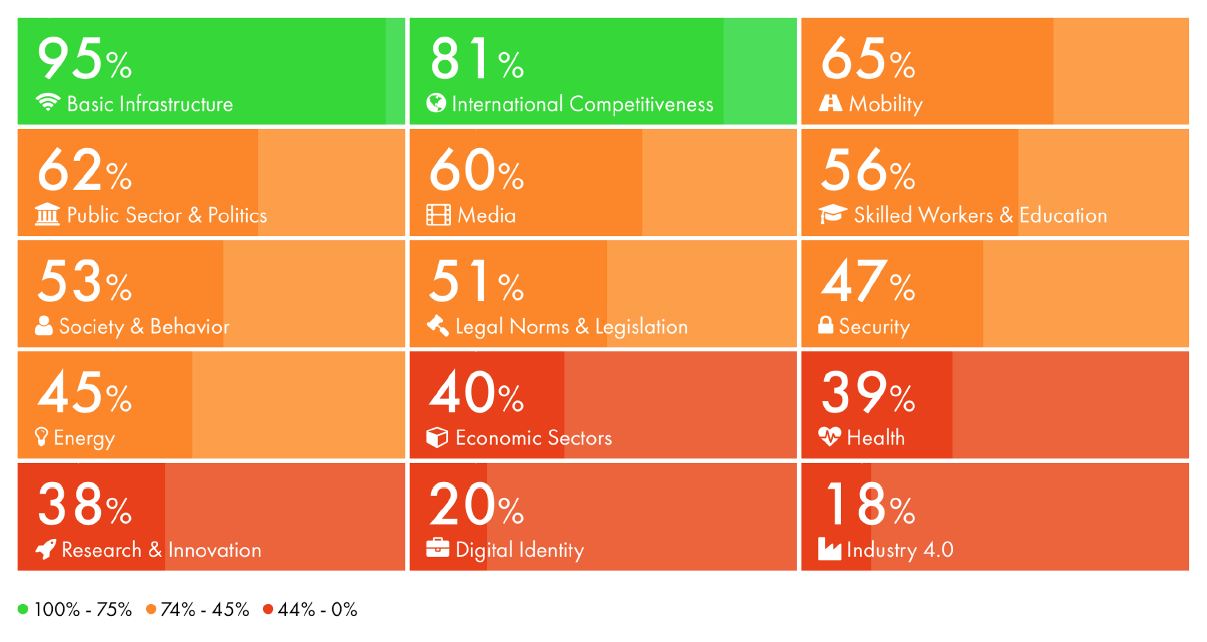

Take the example of Europe’s digital economy. Its size, growth, and contribution to GDP have been far less impressive than in other comparable economic regions like the United States. While Europe has a problem with fragmented markets in the field of digital services, a far bigger hindrance to growth is the highly regulated services sector that inhibits the diffusion of new digital technology from rippling through economies. […However ] past lessons of dynamics competition, especially in sectors where technology has driven competition, suggest that temporarily high market shares for some companies are beneficial. [Page 236] [Again a complex situation]

– Nurturing a culture of dissent and eccentricity

There is a final point to be made. Because it is more about culture than policy, it does not lend itself to a program of reforms. It concerns eccentricity, or the leeway given to these innovators and entrepreneurs who do not conform to the norm. And it is about dissent, and the freedom people enjoy to articulate and pursue their ideas. A culture of dissent and eccentricity is of great importance to innovation – and not just to invention or technology creation. For economies to be innovative, there has to be tolerance of the unknown and acceptance of experimentation. [Page 237]

After this too long presentation, I must end with two quotes, one famous and the other almost unknown. If you have arrived here, you have the right to ask me who are the authors…

Here’s to the crazy ones. The misfits. The rebels. The troublemakers. The round pegs in the square holes. The ones who see things differently. They’re not fond of rules. And they have no respect for the status quo. You can quote them, disagree with them, glorify or vilify them. About the only thing you can’t do is ignore them. Because they change things. They push the human race forward. While some may see them as the crazy ones, we see genius. Because the people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world, are the ones who do.

“Entrepreneurs are the revolutionaries of our time. Democracy works best when there is this kind of turbulence in the society, when those not well-off have a chance to climb the economic ladder by using brains, energy and skills to create new markets or serve existing markets better then their old competitors”