Do you know Morten Lund? You just need to know he was a early investor in Skype.

He was recently in St Gallen, you can watch his talk or read the interview below. Nothing really new, but quite interesting. Thanks to Jordi, for the link 🙂

Jordi apparently read it on the new platform Inno-Swiss

All that follows are Morten’s words, not mine…

Here is a pretty good interview from the programme (with my comments):

Speaking of “the entrepreneur” is always tricky, as there is no clear-cut definition. One way of approaching this problem is to ask entrepreneurs themselves what they think entrepreneurship is all about. Let us hear first from the serial entrepreneur Morten Lund (DK) who covers this year’s topic in a most comprehensive way. He is young, he is famous for having invested very early in the VoIP service Skype, he learnt the ups and downs of entrepreneurship the hard way and he is realistic about the outcome of entrepreneurial endeavours – even those of the St. Gallen Symposium.

Morten Lund, there are a lot of investment opportunities out there right now. You, as an entrepreneur, must enjoy yourself a lot.

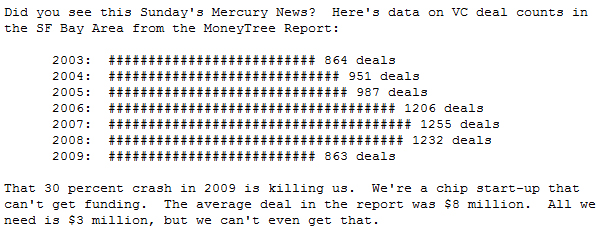

I am bankrupt at the moment (I was when I did the interview), so I cannot do a lot, but then, on the other hand, I can help other people start mind-blowing businesses. In a downturn like this, most entrepreneurs move in the opposite direction to the cycle. When everything collapsed two years ago, a lot of people where investing in start-ups they did not know anything about. (Including myself)

How this?

The clever guys, they cashed in two and a half years ago ( I know quite some) and they are now buying up like crazy from all the bankrupt guys (idiots) like me. For real start-ups, like what I have been doing in technology, this time is, of course, amazing. The reason is that this technology is now mature. Both from the consumer side, as people are using computers all the time and they buy a lot online, and from the technology side, where it has become so easy to develop a website or a web service or to rent servers.

For instance, you have the world’s biggest infrastructure at Amazon which you can just tap into with no set-up fee. So those two components, the e-side and the consumer side, work now and the developers and infrastructure are amazing, and then combine this with the fact that you can actually get developers because they have been fired and are much more realistic salary price-wise – that is all together probably the biggest opportunity in technology history.

What is your part in this game?

Imagine how we would have gone to the cattle market a hundred years ago and seen that perfect cow that gives milk, delivers some good babies and lots of meat you can eat. These are all the processes in the game in which I have been for over 15 years, creating companies, and through trial and error, finding those perfect cows that actually deliver (Christian and Assen – dont be offended :). And now, the technology and the people who want to buy and use it have combined in a way that suits someone like me perfectly. And that is, of course, a dream.

Is it the right time for entrepreneurs? Are they agents of change?

An agent of change for me is more somebody who is standing outside and wants to label people like me. But it is impossible to put a label on me. I am not a consultant, I am not an investor, I am not even an entrepreneur, I am many things in one.

So what are you?

I am mostly a guy facilitating a trampoline. I am the guy who dares to jump the crazy jumps on the trampoline and that people try out like a trampoline. I am facilitating a catapult. The best you can do now is to launch start-ups with good people, but you do have to have simply amazing, crazy, smart, good, cool, nice people, because these kinds of people can challenge SAP in one of their niches. But they have to be amazingly smart, hard working, into their stuff and vibrant. And they have to complement each other perfectly. Then, with added luck, it is possible.

What are the ingredients of entrepreneurial success?

Entrepreneurs are executing a vision and turning it into reality. You need a lot of skills in that process – accounting skills, sales skills, people skills, science skills, presentation skills and so on. The entrepreneur closes his eyes and lowers his hands, then uses all he has himself and reaches out to the world for the best of the competences to make it happen.

He has to be smart and trustworthy and socially strong enough to make his thing take off. How many times have you drawn your small ideas on a piece of paper for your friend but they never became reality. It is the entrepreneur who has the (mental) capital to get the idea off the piece of paper and into sales.

It is about skills, but it is also about luck, is it not?

In my world everybody knows that you have to work superhard (and be disciplined like hell). But then remember, there are global opportunities with technologies and the internet, but there is also global competition.

There will be another two hundred start-ups, some in the same market as you, so you also have to be lucky to break through or to find the right people or to chose the right strategy or to find the first client and adapt all of those things as you go along. You always have to acknowledge luck as part of your entrepreneurial success.

And sometime you fail.

That is why I am apparently so interesting. A lot of people tried what I tried, they have been categorised either as geniuses or losers. If you are one of those people in history who actually dares to talk about the fact that you failed, it seems very strange. And Ooh! If you are honest and talk about failure, that seems to be very new.

Do we need more of a failure culture?

Maybe we do have to be more realistic. So when we have an entrepreneur symposium at St. Gallen, we could also have a failure symposium because failure is much, much more likely than success if you are an entrepreneur. But you do not want to talk about it. I mean, eight out of ten seminars fail. It is very important for you to have the courage to say “I will”, “I can”, “I dare to do this”, but also “I can and dare and see that I can fail”. Then you become really strong.

But is the entrepreneur as an individual not massively overrated?

Again, you want to put a label on it, you want to categorise people. There are very few one-man brands in the world. Michael Jackson did it. (But)Everybody would acknowledge that he needed the band to create the music. In entrepreneurship, as well, you have the initial guy who starts something or who finds the team. But entrepreneurship is much more about team work and group effort.

There is a saying that true entrepreneurs are long-term oriented. But your entrepreneurial career does not reflect that in any way.

I would love to have a long-lasting business that I could keep forever (EVEBREAD = Everlasting Bread and is my dream of a such company). I would love to have this green tech company that purifies water of which I would be the proud owner forever. I think we all would love that. But with entrepreneurship you really have to remember that the entrepreneur can take the idea off a table and turn it into some kind of sales or product. The big corporations will then be so happy to buy this when it works, because they know how to make a critical thing huge. That is why they have a big corporation.

They do not believe they can be innovative at the same level, so they want to buy as soon as an entrepreneur has started. And they are much better at the managing game when you get to a certain level. So I get in quick, get out quick, it is true. Because it pretty often happens that you cannot say no if somebody wants to buy your stuff. The entrepreneurs in charge can get a lot of money, and most of the entrepreneurs, me especially, will take this money and do more of what they did before, meaning turning ideas into reality.

In your opinion, what is the best political and social context for entrepreneurship?

Put crudely, the best model for entrepreneurship in history is the model of American society, because it has created the Gates, the Carnegies and most of the biggest companies we know in a very short time. The Americans can beat anyone and every start-up because they always have the best start-ups and the most successful (financial eco-system until now). Talking about the best social model or political climate for entrepreneurship, I think we have been pretty lucky in the Scandinavian countries, but I doubt whether it is sustainable. (China and India will eat us alive :)

You have to be hungry to be a successful entrepreneur. You have to want to prove to the world, especially coming from small countries like Switzerland (and Denmark), that you can do it. The Nordic model makes people too demanding, they are not hungry any more (dinner is served for free no matter how stupid you behave). That is unfortunate, because I love to live here. Denmark is facing some real shit now. It will be very difficult to keep up all these crazy standards of social living.

Are entrepreneurs role models?

Yes, because we think that entrepreneurship is something we want (have) to do. But we forget that being an entrepreneur can mean failure. Successful entrepreneurs are role models, but seven out of ten entrepreneurs are not role models because they fail.

Interview: Johannes Berchtold

40th St. Gallen Symposium