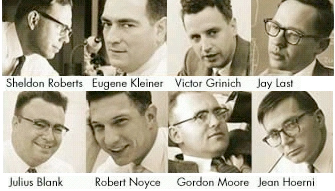

A short quiz: who are the people on the picture?

The answer can be found here. I also tried to do the exercise and you just have to scroll down.

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

A short quiz: who are the people on the picture?

The answer can be found here. I also tried to do the exercise and you just have to scroll down.

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

When I heard about a talk on innovation at Google, I was obiously interested all the more that the brief summary looked great. here is the video on youtube, and below the summary:

>

It was given by Dan Russell, Research Scientist and Search Anthropologist, Google and was part of the Series of the CITRIS Research Exchange from UC Berkeley on March 16, 2011.

12:00 p.m.

Wednesday, March 16

Banatao Aud., 3rd floor, Sutardja Dai Hall, UC Berkeley

http://events.berkeley.edu/?event_ID=39124

About the talk:

As a company, Google clearly relies on innovation to keep our business alive and growing. Translating that desire into a continual innovation practice is central to the outlook and world-view that Google has as a corporate culture. Innovation isn’t just for the futurists, but a part of what everyone in the company is expected to do on a day-to-day basis.

People who work on internal processes, for example, are expected to be as innovative as engineers and product managers who drive externally visible products. Innovation isn’t something that the company can just leave to a few bright minds, but is deeply embedded in the culture of the company.

Beyond culture, though, there are a few pragmatic behaviors that help Google be innovative. A commonplace belief is that innovation originates with an identified market or user need. While we design for the user, we recognize that innovative ideas originate in many places—sometimes with user needs, but also occasionally from technology opportunities that suddenly become available. In these cases, the user need might not be clearly identified at the outset of research, but become evident only over time. Ultimately, of course, an innovation has to be user-relevant, but we understand that not everything starts that way.

One of the key drivers of Google innovation is our focus on data-driven analytics of our products. We instrument just about everything we can think of, log the data (anonymizing along the way to preserve privacy), then analyze it extensively. We recognize that innovation often proceeds in an evolutionary fashion, and that apparently large leaps in design and novel concepts are often hidden beneath a great deal of under-the-covers work the precedes the public announcement.

In user-interface design, for example, we don’t just do A/B testing, but often A/B/C/D/E/F/… testing. And one of the deep lessons of such an extensive testing program is that we recognize that our intuitions are often incorrect. Large changes in the design may very well lead to poor performance shifts, while tiny, sometimes imperceptible changes can have profound consequences. In many of our products, the UI changes significantly over time, particularly as we learn from our experiments, but also as new technology and data becomes available.

Innovation is thus often smoothly evolutionary, albeit looking like punctuated evolution from the outside, but driven by continual rapid iteration and redesign, always driven by an objective function that includes goodness-of-fit to the environment and exaptation of opportunities as they arise.

Finally, we find that innovative products really are the product of many minds. A very small team might drive the initial design and creation of the concept, but having multiple people look at, evaluate, comment-upon and lend supporting insights is valuable. The trick is to allow these additional insights to be supportive, and not weigh the original ideas down with extraneous freight. Keeping an innovation clear, clean and useful to the consumer is an important practice to avoid losing the key insight and value in the innovation.

Thanks to a conversation with an EPFL colleague, I was recently reminded the early history of Silicon Valley. I knew about Shockley, Fairchild and the Traitorous Eight. I did not know Shockley had been funded by Beckman (thanks Andrea :-)), that was the point of the recent conversation.

What is interesting is to have a look at the Traitorous 8 also. Their history (cf Wikipédia) is well-known, what may be less known is their background.

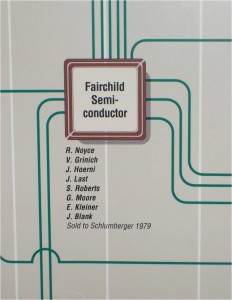

The next table gives the origin, education and age of the 8 traitors, the 8 engineers who left Shockley labs to found Fairchild Semiconductor in 1957 (click on it to enlarge).

They can be considered as the real fathers of Silicon Valley. The famous poster entitled Silicon Valley Genealogy is certainly a convincing illustration of it as well as their Post-Fairchild activities.

The next image is extracted from the one above (left, mid-height level, corresponding to 1957).

A few comments:

– 5 were educated on the East Coast, 2 on the West Coast and 1 in Europe.

– Indeed, three were from Europe.

– 6 had a PhD (3 from MIT), all had a bachelor.

– They were between 28 and 34-year old in 1957.

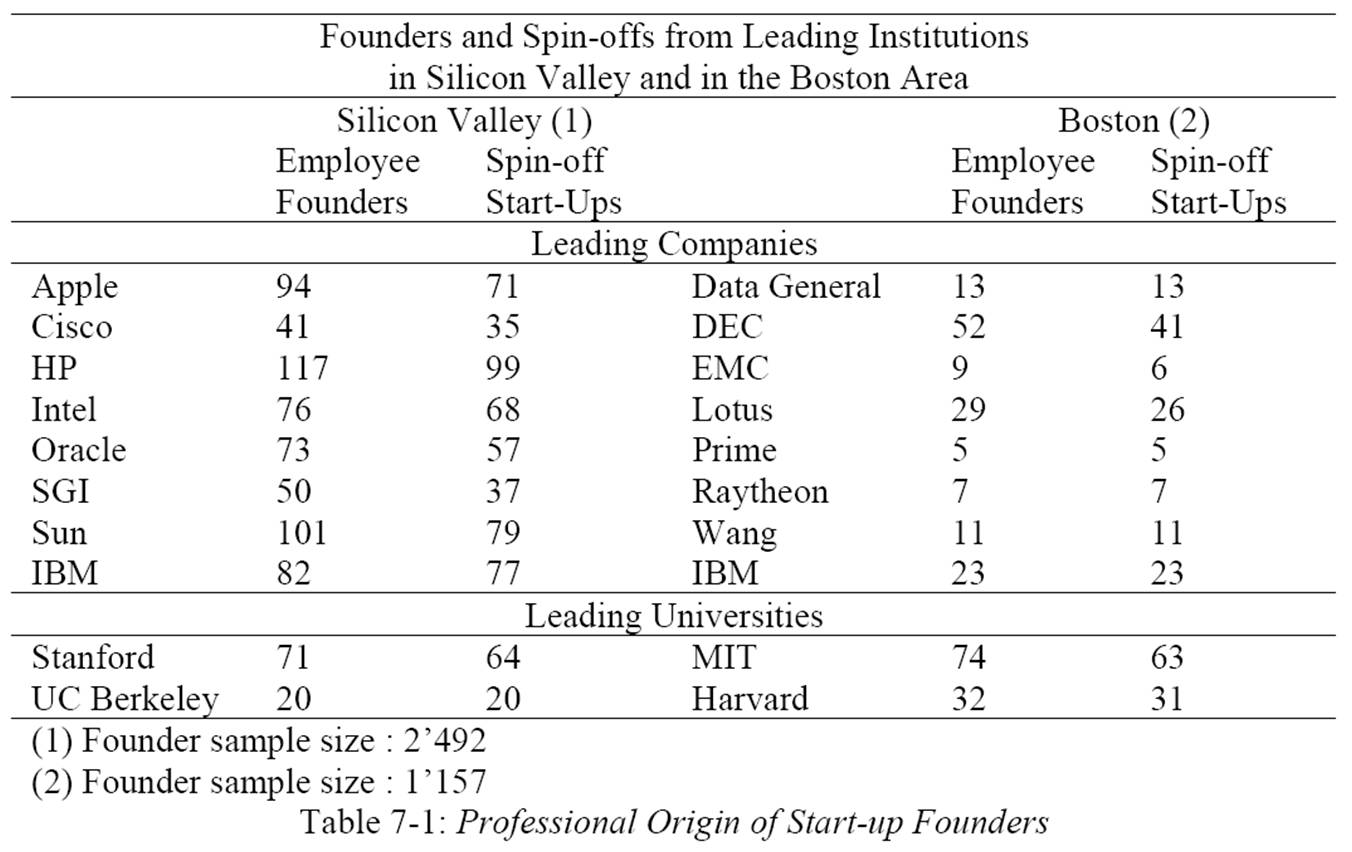

It’s one of Silicon Valley strongest assets: entrepreneurs do not stay for long in established companies and create new ones. And it is accepted as a fact. Let us just me quote again Richard Newton: “The Bay Area is the Corporation. […When people change jobs here in the Bay Area], they’re actually just moving among the various divisions of the Bay Area Corporation.”

And what about the famous Wagon Wheel bar: “During the 1970s and 1980s, many of the top engineers from Fairchild, National and other companies would meet there to drink and talk about the problems they faced in manufacturing and selling semiconductors. It was an important meeting place where even the fiercest competitors gathered and exchanged ideas.”

The story goes on. I read today (thanks to Burton Lee) 15 Interesting Startups From Ex-Googlers from Jay Yarow. He found that since 2004, 49 spin-offs were created by former “Googlers”. Because it was a work in progress, apparently the number has increased to more than 70. See slide 2 of the pdf.

As a conclusion, let me add a study by Junfu Zhang who compared Silicon Valley to the Boston Cluster, in terms of how many entrepreneurs left their big company. He showed the big difference there was between the two regions that both Newton and the Wagon Wheel bar explain in terms of culture.

Source: High-Tech Start-Ups and Industry Dynamics in Silicon Valley – Junfu Zhang – Public Policy Institute of California – 2003

Thanks to an opportunity I got to meet with the Israel Chief Scientist, and the fact I was offered Start-Up Nation at the end of the meeting, let me give you my views on this very interesting book. But first a few things about Israel and innovation.

As the map (adapted from John Kao, Harvard and showed at the OCS meeting) indicates, Israel is an innovation superpower. Cisco, Intel, Microsoft, Novartis, Nestle and many others are located there. Check Point is just one of the many start-up success stories. Israel has more start-ups quoted on Nasdaq than Europe and venture capital is very active there. Finally the office of the chief scientist manages and funds the public side of innovation in Israel. All this is perfectly analyzed in the book Start-Up Nation that I have just read.

I thought I knew a lot about Israel, but the book is rich in anecdotes. The history of Israel is well described and innovation was probably a necessity to survive. If there is a point I appreciated less is the importance the authors give to the military. They may be right, that’s not the point, but I thought the topic came too often in the chapters. This remains a great book and a must read for anyone interested in high-tech innovation and entrepreneurship.

I’d like now to quote a few things I liked. It’s not structured at all, but I invite you to read the book!

From the Introduction

Google’s CEO and chairman, Eric Schmidt said that the United States is the number one place in the world for entrepreneurs, but “after the U.S., Israel is the best.” Microsoft’s Steve Ballmer has called Microsoft “an Israeli company as much as an American company” because of the size and centrality of its Israeli teams.”

The authors begin by explaining that adversity and multidimensionality as much as the talent of individuals, are critical: “it is a story not just of talent but of tenacity, of insatiable questioning of authority, of determined informality, combined with a unique attitude toward failure, teamwork, mission, risk, and cross-disciplinary creativity.”

Chapter 1- Persistence

The usual joke Americans need to put, but it is a good one!

Four guys are standing on a street corner . . .

an American, a Russian, a Chinese man, and an Israeli. . . .

A reporter comes up to the group and says to them:

“Excuse me. . . . What’s your opinion on the meat shortage?”

The American says: What’s a shortage?

The Russian says: What’s meat?

The Chinese man says: What’s an opinion?

The Israeli says: What’s “Excuse me”?

—MIKE LEIGH, Two Thousand Years

– No inhibition about challenging the logic behind the way things have been done for years.

– A rude, aggressive culture which tolerates failure.

– Israeli attitude and informality flow also from a cultural tolerance for what some Israelis call “constructive failures” or “intelligent failures.”

– It is critical to distinguish between “a well-planned experiment and a roulette wheel

(During the meeting with the chief scientist, there was a similar argument: “if we have a 5% success rate, we’d better give the responsability to donkeys to choose and if it is 70% success rate, we do not take enough risks”)

– Amos Oz talks about “a culture of doubt and argument, an open-ended game of interpretations, counter-interpretations, reinterpretations, opposing interpretations. From the very beginning of the existence of the Jewish civilization, it was recognized by its argumentativeness.”

Chapter 2- Lesson from the military

– Narrow hierarchy and autonomy gives a lot of responsibility to individuals, authority is discussed

– People are mature earlier.

– No need to wait for order to act.

– “The key for leadership is the soldiers’ confidence in their commander. If you don’t trust him, if you’re not confident in him, you can’t follow him.”

– “If you aren’t even aware that the people in the organization disagree with you, then you are in trouble”

– “Real experience also typically comes with age or maturity. But in Israel, you get experience, perspective, and maturity at a younger age, because the society jams so many transformative experiences into Israelis when they’re barely out of high school. By the time they get to college, their heads are in a different place than those of their American counterparts.”… “The notion that one should accumulate credentials before launching a venture simply does not exist.”

A dense network – the whole country is one degree of separation (Yossi Vardi)

Chapter 5- Order and chaos

– Singapore’s leaders have failed to keep up in a world that puts a high premium on a trio of attributes historically alien to Singapore’s culture: initiative, risk-taking, and agility; in addition to being real experts who can improvise in situations of crisis.

– Innovation is fundamentally an experimental endeavor (improvisation over discipline)

– Learn from mistake with no fear of losing face.

– Nobody learns from someone who is being self defensive

– Fluidity, according to a new school of economists studying key ingredients for entrepreneurialism, is produced when people can cross boundaries, turn societal norms upside down, and agitate in a free-market economy, all to catalyze radical ideas.

Chapter 7 – Immigration

Immigrants are not averse to starting over. They are, by definition, risk takers. A nation of immigrants is a nation of entrepreneurs.—GIDI GRINSTEIN

Sergey Brin spoke in an Israeli high school: “Ladies and gentlemen, girls and boys,” he said in Russian, his choice of language prompting spontaneous applause. “I emigrated from Russia when I was six,” Brin continued. “I went to the United States. Similar to you, I have standard Russian-Jewish parents. My dad is a math professor. They have a certain attitude about studies. And I think I can relate that here, because I was told that your school recently got seven out of the top ten places in a math competition throughout all Israel.” This time the students clapped for their own achievement. “But what I have to say,” Brin continued, cutting through the applause, “is what my father would say—‘What about the other three?

The authors mention the seminal work of AnnaLee Saxenian (Regional advantage, the New Argonauts). As a few examples of Israel tech. diaspora mentioned in the book:

– Dov Frohman – Intel – 1974 – Wikipedia link. Apparently Israel has been the core of Intel innovation in the past decade and Intel is the largest private employer in Israel.

– Michael Laor – Cisco – 1997 – Linkedin profile. Cisco has acquired 9 israeli start-ups since Laor came back (more acquisitions than in any other country except the USA)

– Yoelle Maarek – Google – http://yoelle.com now at Yahoo!

But one should not forget Mirabilis/ICQ (see below) or Check Point. Check Point was established in 1993, by the company’s current Chairman & CEO Gil Shwed, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gil_Shwed at the age of 25, together with two of his friends, Marius Nacht (currently serving as Vice Chairman) and Shlomo Kramer (who left Check Point in 2003 to set up a new company).

Chapter 9 – Yozma

Another member of the tech. diaspora: Orna Berry – PhD USC – Unisys-IBM then Ornet and Gemini then OCS chief… The VC industry was really launched through the Yozma effort as well as Israeli incubators. Gemini was the first Israel fund. See the wikipedia article about venture capital in Israel.

Another quote on start-ups vs. more mature industries: “In aerospace, you can’t be an entrepreneur,” he explained. “The government owns the industry, and the projects are huge. But I learned a lot of technical things there that helped me immensely later on.”

Chapter 12 – Transdisciplinarity

“There’s a multitask mentality here.” The multitasking mentality produces an environment in which job titles—and the compartmentalization that goes along with them—don’t mean much.

– “Combining mathematics, biology, computer science, and organic chemistry at Compugen”

– “Putting this together required an unorthodox combination of engineering skills.”

The term in the United States for this kind of crossover is a mashup. And the term itself has been rapidly morphing and acquiring new meanings. … An even more powerful mashup, in our view, is when innovation is born from the combination of radically different technologies and disciplines. The companies where mashups are most common in Israel are in the medical-device and biotech sectors, where you find wind tunnel engineers and doctors collaborating on a credit card–sized device.

But the authors do not forget to mention that Israel is A country with a motive

Role models

Though Israel was already well into its high-tech swing by then, the ICQ sale was a national phenomenon. It inspired many more Israelis to become entrepreneurs. The founders, after all, were a group of young hippies. Exhibiting the common Israeli response to all forms of success, many figured, If these guys did it, I can do it better. Further, the sale was a source of national pride, like winning a gold medal in the world’s technology Olympics.

“There’s a legitimate way to make a profit because you’re inventing something,” says Erel Margalit “You talk about a way of life—not necessarily about how much money you’re going to make, though it’s obviously also about that.”

“Indeed, what makes the current Israeli blend so powerful is that it is a mashup of the founders’ patriotism, drive, and constant consciousness of scarcity and adversity and the curiosity and restlessness that have deep roots in Israeli and Jewish history. “The greatest contribution of the Jewish people in history is dissatisfaction,” Peres explained.

Again “Not just talent, but tenacity, insatiable questioning of authority, determined informality, unique attitude toward failure, teamwork, mission, risk and cross-disciplinary creativity.”

As a conclusion

“So what is the answer to the central question of this book: What makes Israel so innovative and entrepreneurial? The most obvious explanation lies in a classic cluster of the type Harvard professor Michael Porter has championed, Silicon Valley embodies. It consists of the tight proximity of great universities, large companies, start-ups, and the ecosystem that connects them—including everything from suppliers, an engineering talent pool, and venture capital. Part of this more visible part of the cluster is the role of the military in pumping R&D funds into cutting-edge systems and elite technological units, and the spillover from this substantial investment, both in technologies and human resources, into the civilian economy. … But this outside layer does not fully explain Israel’s success. Singapore has a strong educational system. Korea has conscription and has been facing a massive security threat for its entire existence. Finland, Sweden, Denmark, and Ireland are relatively small countries with advanced technology and excellent infrastructure; they have produced lots of patents and reaped robust economic growth. Some of these countries have grown faster for longer than Israel has and enjoy higher standards of living, but none of them have produced anywhere near the number of start-ups or have attracted similarly high levels of venture capital investments. What’s missing in these other countries is a cultural core built on a rich stew of aggressiveness and team orientation, on isolation and connectedness, and on being small and aiming big. Quantifying that hidden, cultural part of an economy is no easy feat. An unusual combination of cultural attributes. In fact, Israel scores high on egalitarianism, nurturing, and individualism. In Israel, the seemingly contradictory attributes of being both driven and “flat,” both ambitious and collectivist make sense when you throw in the experience that so many Israelis go through in the military. There is no leadership without personal example and without inspiring your team. The secret, then, of Israel’s success is the combination of classic elements of technology clusters with some unique Israeli elements that enhance the skills and experience of individuals, make them work together more effectively as teams, and provide tight and readily available connections within an established and growing community.

If you have arrived here, you were interested enough in this long article. Logically, your next move would be to buy Start-Up Nation!

I found instructive to compare two short videos from the STVP. The first one is dated 2002 and shows Larry Page, the co-founder of Google. The seconde one, with Aaron Levie, has just been published on january 19, 2011.

And here is a comparaison

| Larry Page | vs. | Aaron Levie |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Clearly passion, ambition but also self-confidence are ingredients of entrepreneurship.

Another very good post on the topic is Should You Really Be A Startup Entrepreneur? by Mark Suster, where the reality of entrepreneurship is superbly described.

Following my recent post, Is there something rotten in the state of IP, I could not avoid to add this provocative statement despite all my respect for venture capital. When Kleiner Perkins, one of the best West Coast VC (not to say one of the best VC ever), Charles River, one of the best East Coast VC and Index, one of the best European VC co-invest in an IP company (a “Patent Risk Manager”) such as RPX, I thought there had been a major event. And Randy Komisar who is mentioned in my latest post is on the board… Now RPX is filing to go public so as I do usually, here is the cap. table. All these data remain subject to the IPO date and share price which I just had to imagine… You may also be interested to know that the founders of RPX come from Intellectual Ventures…

I have been surprised not to read more about Intellectual Ventures’ recent legal actions. You can read more about the companies they are suing for infringing IV’s IP.

If you do not know about Intellectual Ventures, you should know they have filed or bought about 30’000 patents or patent applications and raised billions of dollars. Until now, nobody really knew why, but their recent actions show IV is just another patent troll.

Around the same period, Paul Allen has been dismissed by a judge about the complaint he had filed for another patent infringment. More here. I should add I read about both pieces of news thanks to the Xconomy web site.

This is an opportunity to say that I have never been a big fan of IP, intellectual property, patent applications and copyrights. I do not have good alternatives to propose, but innovation is often more a matter of speed and being more advanced that being protected by IP. I am aware it is not so simple though. I have worked in the field for a while and I still give general courses on the topic. Those interested may click on the picture below or on this link.

Intellectual Ventures was founded by Nathan Myhrvold, who was formerly CTO at Microsoft. Not need to add which role Paul Allen had at Microsoft. All this could be funny when you think about the fact Microsoft success was not based on patents (and Microsoft did not suffer that much from all the people who copied all their software…)

I was invited this morning on RSR, the (french-speaking) Swiss National Radio, to talk about innovation and start-ups in their morning (5am to 6am!) Petits Matins. For those who know about the topic, nothing fundamentally new, with the slight exception that I learnt recently that a common feature to many entrepreneurs would be dyslexia (two studies were made in the USA and the UK). In total, a 30-minute conversation on my favorite topic, that you may listen on the RSR website if French is a language you like. Many thanks to Manuela Salvi, the talended RSR journalist.

More importantly, I could invite a guest on the phone at 5:45am (what a gift!) I was delighted to let Peter Harboe-Schmidt talk about his novel The Ultimate Cure, a beautiful thriller with a Lausanne-based biotech start-up as the background. I had already mentioned that book on this blog. Peter just announced the novel had just been translated in French.

Steve Blank is famous in Silicon Valley as an entrepreneur and teacher of entrepreneurship. In particular, he has a Secret History of Silicon Valley which shows the importance of the military and cold war in its development.

He recently published a very optimistic blog When It’s Darkest Men See the Stars.

He claims entrepreneurship barriers are changing. These were:

1. long technology development cycles (how long it takes from idea to product),

2. the high cost of getting to first customers (how many dollars to build the product),

3. the structure of the venture capital industry (a limited number of VC firms each needing to invest millions per startups),

4. the expertise about how to build startups (clustered in specific regions like Silicon Valley, Boston, New York, etc.),

5. the failure rate of new ventures (startups had no formal rules and were a hit or miss proposition),

6. the slow adoption rate of new technologies by the government and large companies.

And we are facing a new world he calls “The Democratization of Entrepreneurship” and he sees

– A Compression of the Product Development Cycle

– Startups Built For Thousands Rather than Millions of Dollars

– A New Structure of the Venture Capital industry

– Entrepreneurship as Its Own Management Science

– Consumer Internet Driving Innovation

I reacted on his blog and wrote this: I have to admit I am puzzled. Let me elaborate.

On the positive side, the optimism expressed is very refreshing and I felt really good after reading it. I tend to agree with the lower barriers to entrepreneurship, and probably I kept my sun glasses in the dark too long, so I do not see the stars. (But I will think this is a great article that I want to mention to my own little network.) But on the other side, I am concerned that the same barriers still exist in biotech, semiconductor (and most hardware products if they embed radical innovations) or even in cleantech/greentech (which by the way maybe be more a bubble than a real new field). In these fields, product development is as long, VCs are afraid sometimes of the capital requirements, Richard Newton, the Berkeley professor (http://www.eecs.berkeley.edu/~newton/presentations), had noticed a long time ago, that most talents go out of these tough fields to easier or more promising fields (it was from electronics to internet in the 90s). It might be that we do not (have to) innovate as much in these classical fields anymore, in which case you are totally right. But if not, we are just moving to the low hanging fruits of innovation, and we are blinded by superstars but do not see the myriads of others (needs, opportunities) we should also focus on…