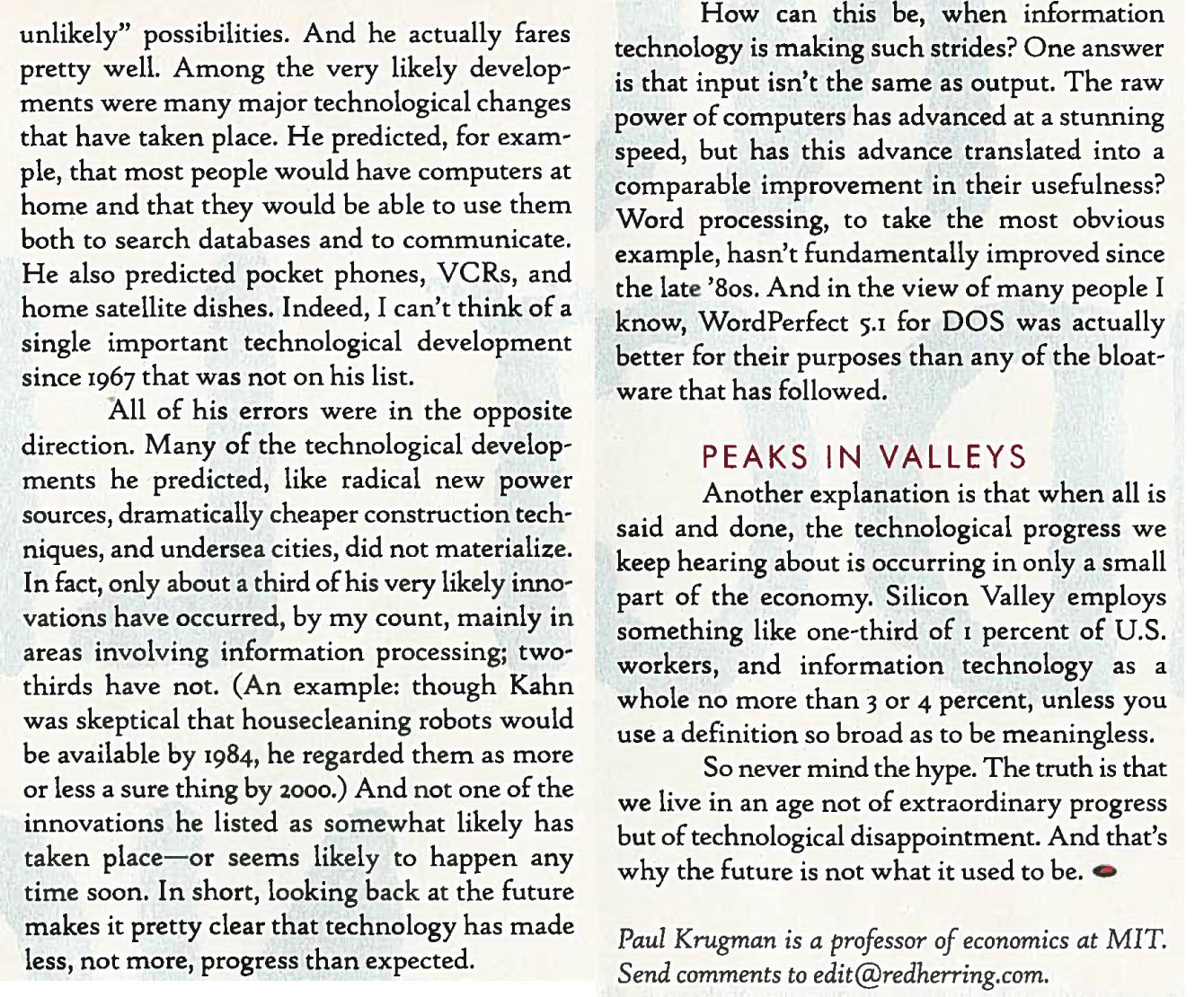

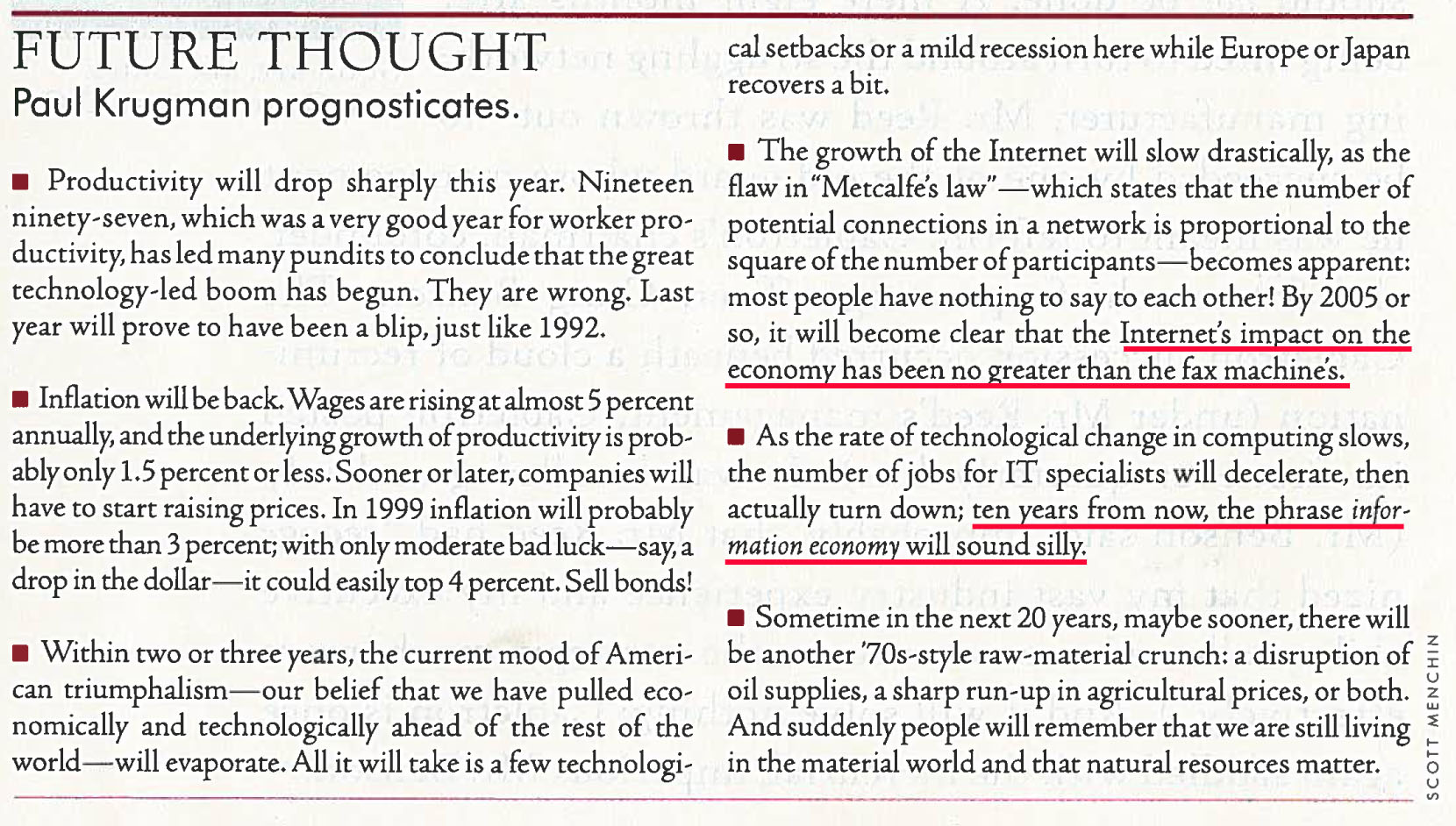

Another fo my recent reading from old Red gerring magazines. The analysis and predictions are great and provide good lessons for our days… In the same feature, October 98, I found small articles about companies we backed at Index. These three companies went public later on… so a small additional piece for nostalgia.

Prepare for dramatic Internet company wreckage.

By Anthony B. Perkins

ONE 0F THE surest reality checks in the technology business is a visit with Don Valentine of Sequoia Capital. Mr. Valentine’s seed money and sound advice have been instrumental in many of Silicon Valley’s greatest success stories, including Apple, 3Com, Cisco, and Yahoo. He, along with Netscape founder Jim Clark, was the first to proclaim in our pages, back in 1994, that Internet was indeed the information highway, and not just a “TV with a pizza box sitting on top” (see “Don Valentine’s Next Big Bet Is on C-Cube Microsystems,” May 1994 page 58). We recently prodded the curmudgeonly Mr. Valentine to tell us how he thinks the Internet market will play out. His insights are instructive.

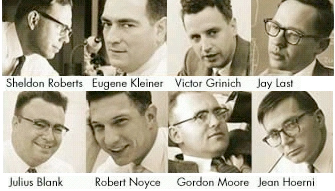

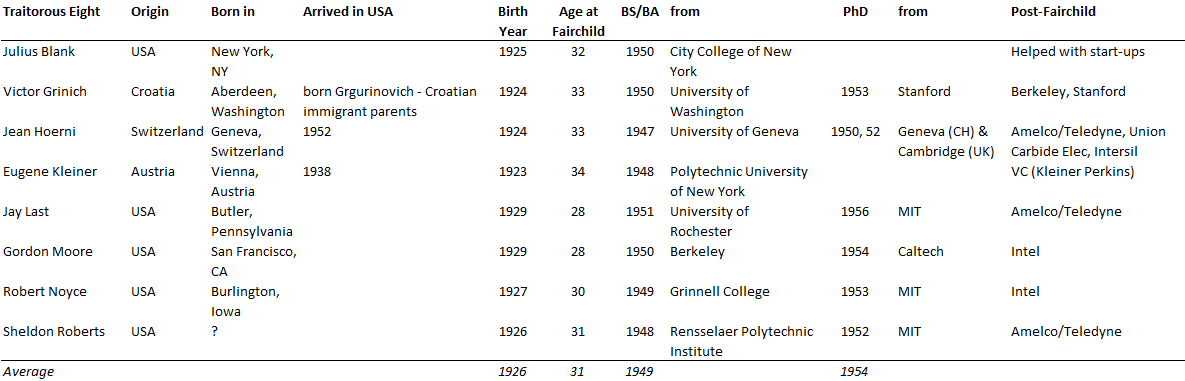

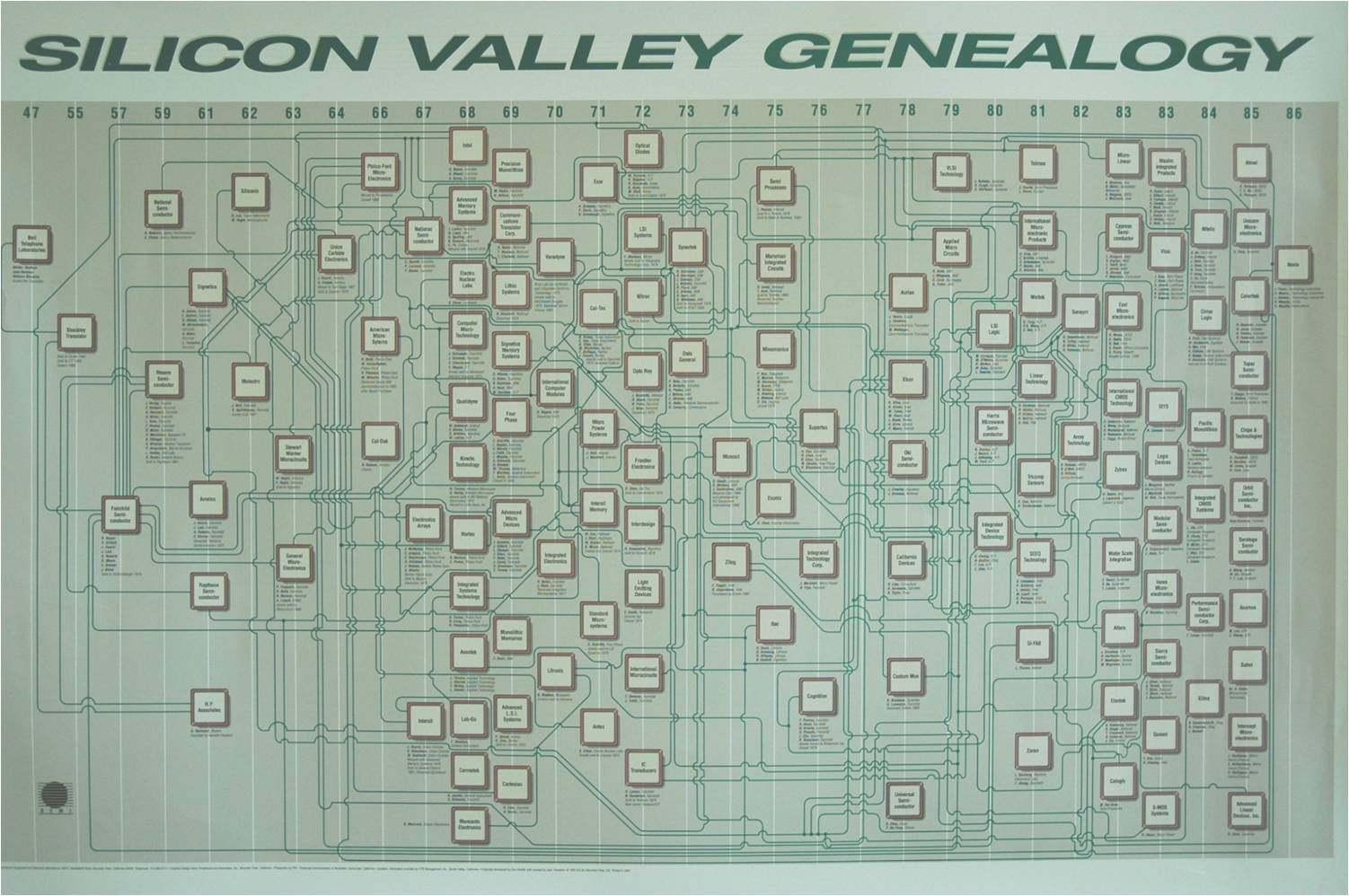

First he notes that, like the microchip and PC markets, the Internet market grew organically rather than because it solved any obvious problem that was important to a large group of people who had a lot of money. Mr. Valentine recounts being at Fairchild Semiconductor when he and future Intel founder Bob Noyce marveled at the invention of the microchip but at the same time wondered what it was good for. The early days at Apple were much the same. “I remember wondering what people were going to do with the Apple II. There was no answer!” Mr. Valentine declares. In contrast, the networking boom was about solving big, important problems for corporations. “When Cisco came along, it was addressing an environment desperately in need of a solution,” he explains.

From a venture capital perspective, Mr. Valentine believes that it is better to invest in markets clamoring for new products than in creating new markets. “In the two previous eras—microchips and PCs—lots of companies went over a cliff,” he says. “Uniquely in the networking world, there are almost no busts.” Extending his logic, Mr. Valentine foresees what we have been predicting for a couple of years now that the Internet space will suffer dramatic company wreckage as well. Another veteran VC, Jim Breyer of Accel Partners, concurs with this analysis: “Ninety percent of the Internet companies that exist today will eventually go out of business.” And Mary Meeker of Morgan Stanley Dean Witter says that roughly 75 percent of the Internet companies that went public in the past four years are now trading below their initial public offering prices.

According to Mr. Valentine, part of the overfunding of these markets-in-creation can be attributed to the infamous herd mentality within the VC community. “We financed 6o disk drive companies because each venture firm wanted to have a disk drive investment in its portfolio,” he tells us. “The reason we have so many search engines is that Yahoo got visible. Lots of VCs didn’t have one of those. So they created an Infoseek or an Excite or whatever, and jumped on the back of the train. We are making the same mistake in the Internet era that we made in the PC era. Just think about the environment. There is no application in which the Internet solves a problem. What does the Interne do so far? It sort of reminds me of the Apple computer in 1978. It doesn’t do anything.”

Mr. Valentine feels certain about one aspect of the Internet: that it represents the most efficient marketplace for goods and services on the planet. “Never before has the consumer had all the cards dealt face up where he can make choices and decisions knowing all the facts,” he says. “In traditional marketplaces, consumers have always had to deal with confusion, arcane language, and obfuscation. Buying something is often a hassle. Insurance is a great example of this; dealing with car salesmen is another. Now consumers are being put in a position in which they have phenomenal access to whatever they want.” This may seem of obvious value to businesses—especially when you look at the revenue trajectory of an Amazon.com or contemplate the 10 million’s worth of computer equipment that Michael Dell is selling online every day— but the only thing that is really obvious is the value to the consumer. We ask the same question that the salty Mr. Valentine does: “How do you make money in this perfect marketplace?” Our problem with Arnazon.com has never been its sales potential; rather, we wonder whether it will make technology-industry-level margins.

I threw Mr. Valentine’s comments out for discussion at dinner last night with Broadview CEO Paul Deninger and Red Herring editor Jason Pontin, inciting a lively debate. From Mr. Deninger’s perspective, Amazon.com may well be the exception, not the rule. “Look, Jeff Bezos at the right place at the right time with the right product,” he said. “But for every Amazon.com, there will be 20 flameouts.” His main point was that “e-commerce is a new way of conducting commerce electronically, but not necessarily a new industry.” Jason piped in with his theory that the disaggregation effect of the Internet “creates room for re-aggregation.” (By this time we had gone through our fourth bottle of wine.) And I believe Jason is quite right. Now that portals have better organized the Web, and Amazon.com has shown everyone how to conduct Internet commerce successfully, it’s time for the rest of the world to jump into the game. Instead of relying on Yahoo and the major portals to organize your experience, you will build your home page with links into the “miniportals” representing your specific interests. Eventually, all major product and service distributors will go online and fend off startups like Arnazon.com that are eyeing their lunch.

One defender of the miniportal revolution is Jim Moloshok, senior vice president of Warner Brothers Online. At our recent Herring on Hollywood conference in Santa Monica, California, Mr. Moloshok au but declared war on Sillcon Valley’s search-engine geeks. He warned Hollywood’s studio producers and new-media types that they are in danger of losing control of their online destinies if they don’t stop giving away their valuable television-, film-, and music-related content to Internet companies starved for programming, and that they should start demanding better licensing terms. “Entertainment companies are mortgaging their online future,” said Mr. Moloshok. “They’re giving away their content in exchange for exposure. But the entertainment companies are basically underwriting these Internet companies by throwing away their intellectual currency.” All this debate left me agreeing with Mr. Valentine’s basic premise: the Internet is still a market-in-creation. Although we have our arms around the idea that it represents a vast and efficient distribution channel and will provide a stream for investment news and entertainment content, its real value has yet to come into focus. And as we grope along this trail, we will continue to see fledgling companies like Broadcast.com and GeoCities go public. But we’ll have to wait a while to sec which cars stay on the road and which ones fly off the cliff.

[For Tony Perkins’s free weekly newsletter, send an email with subscribe in the suhject line to tonynet@redherring.com.]