I enjoyed reading Un paléoanthropologue dans l’entreprise, i.e. a paleoanthropologist in the corporate world, the last book of Pascal Picq, a paleoanthropologist who explores the world of innovation. He applies his knowledge of evolution to compare two types of innovation: by simplifying, Continental Europe, rather Lamarckian and the Anglo-Saxon world and especially the United States, of Darwinian type.

I warn the reader by quoting Picq’s conclusion (page 236): “the Darwinian corporation has nothing to do with all the stupid stereotypes erroneously expressed about evolution. It is a corporation that adapts to changes by mobilizing innovation mechanisms, which are based on the torque variation / selection ”

From the very beginning, we dive into the heart of the matter: “The public officials who are working to open up our French vertical society will see, in the opposition between Lamarck and Darwin, the ineffectiveness of competent organizations facing the fruitful “bricolage” (do-it-yourself) of the networks which create new sources of innovation and development.” And he adds: “Diversity is a prerequisite for innovation.” (Page 12)

Picq explains (page 44): “Natural selection works in two steps, the production of variations – ithat is variability – and, secondly, the selection. It is the Darwinian algorithm.” There is neither chance nor necessity. At each stage of evolution, innovations appear as random variations constrained by history. That’s the game of possibilities.

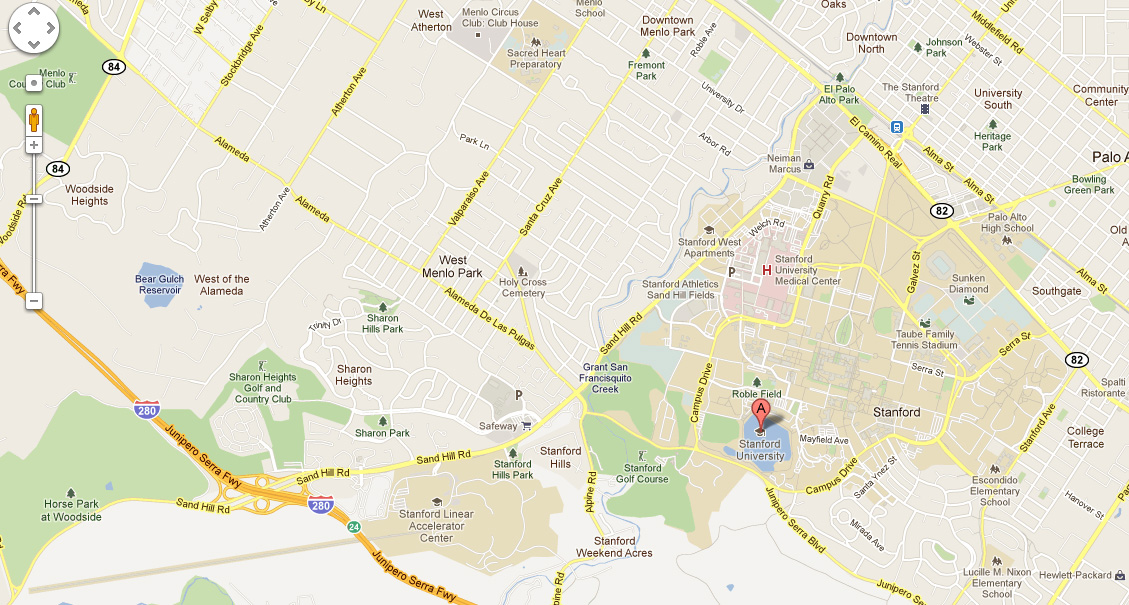

He is well aware that the use of biology to economics analogies is dangerous (page 51): “the concepts of corporations and species are not defined easily.” And the analogy of evolution has probably its limits. “But there’s an important message: variability” (page 52) “If the environment is favorable, there is no selection. If there is competition for resources, then it manifests itself by playing variations. Adaptation comes from this mechanism.” There is no perfect Adaptation, but (page 55) “isolationism is the penultimate step before extinction.” I can not help thinking of the work of Saxenian who has shown that the more closed culture of the Boston area partly explains its lag behind Silicon Valley and the demise of Digital Equipment (DEC).

“There is no perfect adaptation; even if we create the best products, the success or failure depends on many other contextual and contingent factors. The ways of coping are not impenetrable, but take paths and sometimes difficult to predict detours: crafts, breakthrough innovations, and also the return of products once thought obsolete which find new niches. There would be a solution, that of a planned model of needs and uses. Except that between Thomas Edison and Steve Jobs, no major innovation came out of directed economic systems. On the other hand, do we fit in an existing market or do we create new markets? For structural and historical reasons – i.e. cultural – the best European companies are excellent in markets already structured but have difficulty inventing new markets such as U.S. companies.” (Page 84). Earlier, he wrote: “The dominant idea of a technological change that is linear and accumulative obscures a much neglected field of innovation: history.” (Page 63)

“If a new market emerges, everyone has a chance. The absence of pressure from competition and selection admits all possibilities, giving the false impression that one is great. But when the market is saturated or shrinks, this is where selection has a role. This was the case with mobile phones in the mid-1990s. A company like Nokia, historically out of the field of electronics, was able to find its place. In today’s highly competitive market, it would be simply impossible.” (Page 87)

I let the reader discover the concepts of preadaptation, transaptation, exaptation. Picq also describes the K and r strategies which I quote from wikipedia:

– The r-selection: In unstable or unpredictable environments, r-selection predominates as the ability to reproduce quickly is crucial. There is little advantage in adaptations that permit successful competition with other organisms, because the environment is likely to change again. Traits that are thought to be characteristic of r-selection include: high fecundity, small body size, early maturity onset, short generation time, and the ability to disperse offspring widely.

– The K-selection: In stable or predictable environments, K-selection predominates as the ability to compete successfully for limited resources is crucial and populations of K-selected organisms typically are very constant and close to the maximum that the environment can bear (unlike r-selected populations, where population sizes can change much more rapidly). Traits that are thought to be characteristic of K-selection include: large body size, long life expectancy, and the production of fewer offspring, which require extensive parental care until they mature. Organisms whose life history is subject to K-selection are often referred to as K-strategists or K-selected. Organisms with K-selected traits include large organisms such as elephants, trees, humans and whales, but also smaller, long-lived organisms such as Arctic Terns.

Here we are in the heart of the matter:

– Lamarckian innovation (page 158) is active. It responds to a solicitation of the environment and tend to the improvement. “The function creates the organ.”… “Inventions are the daughters of necessity.” It works to improve products in established industries: automotive, aerospace, rail, space, telephone, water, construction, petrochemicals …

– Darwinian innovation (page 160), initially produces diversity without thinking of the advantages or disadvantages of what emerges, then in a second step, there is the action of selection. In such a context, you have to waste time, set the conditions for the production of ideas. It allows serendipity.

These are the 20% free time at Google. He also explains (page 98) the dangers of rationalizing research expenditures (see my post on the need for wasting ideas). Then (on page 103) “Steve Jobs launched Next, without much success, in a culture of the trial and error; it allowed him to propose and test new ideas that led him to come back to Apple – which would have been inconceivable in Europe.”

And here’s his summary (page 139):

| Lamarckian Culture |

Darwinian Culture |

| Continental Europe |

USA |

| Hierarchy of Schools |

Diversity in excellence |

| “I did Polytechnique” |

“I created a business” |

| Uniformity of elites |

Diversity of elites |

| Large Corporations |

“Small Business Act”

|

| Culture of Engineering |

Culture of Research |

| “Agrégés” (teaching) |

PhD (research) |

| Culture of Compliance |

Culture trial and error |

| Managed innovation |

Darwinian algorithm |

| Selection on IQ |

Selection on creativity |

| Applied R&D |

R&D by emergence |

| Colbertism |

Freedom of territories |

| Career |

Entrepreneurship |

| CAC40 |

Top25 |

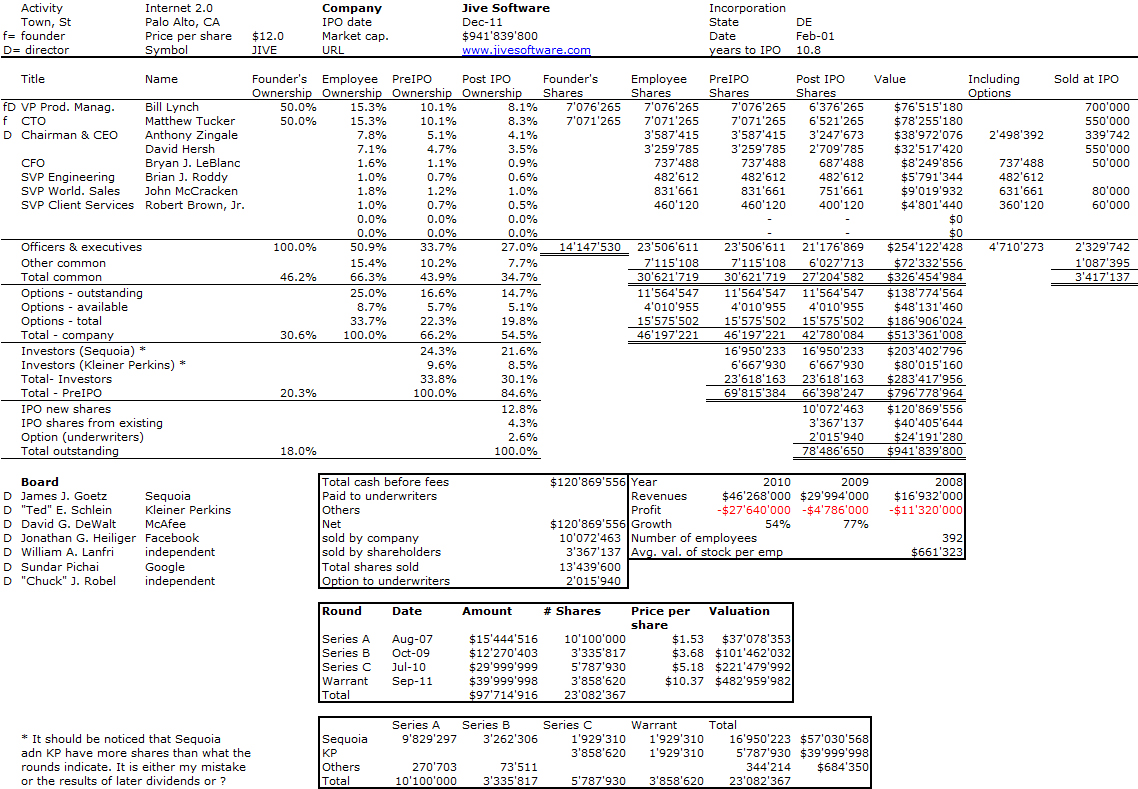

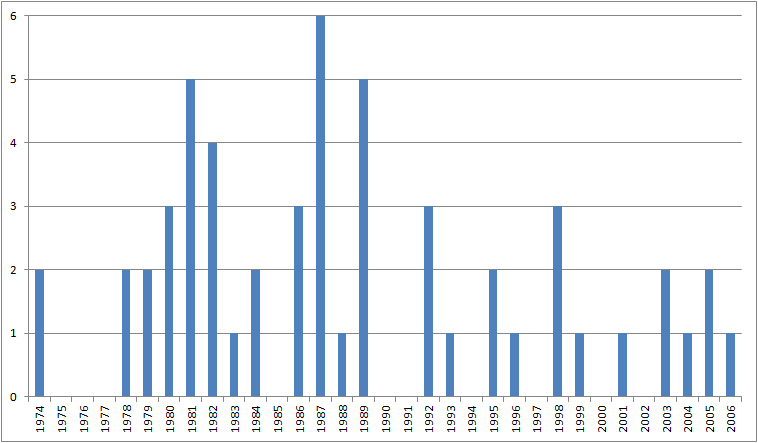

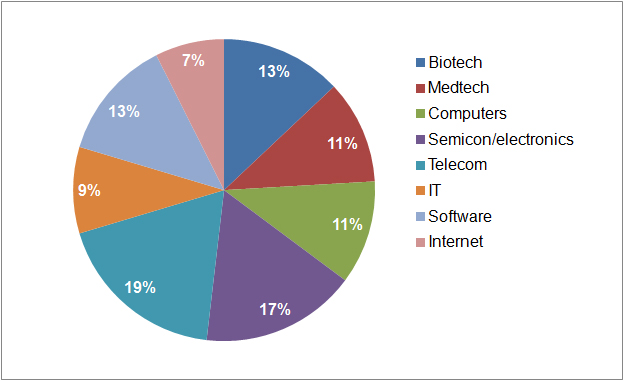

I could have added his distinction (page 222) between Owner/manager of a company and Entrepreneur. Another interesting anecdote: “If you look at the French CAC 40, almost all have been around for half a century. Bertlesmann is the only one being less than 40 years in the European TOP25 whereas there is one third in the United States.” I mentioned this in Start-Up by citing the work of Zhang Junfu. “Zhang also analyzed this astonishing dynamics by comparing the 40 biggest high-tech Silicon Valley companies in 1982 and in 2002 as provided by Dun & Bradstreet. Twenty of the 1982 companies did not exist anymore in 2002 and twenty one of the 2002 companies had not been created in 1982.” Here it is in full:

Forty Largest Technology Companies in Silicon Valley

| 1982 |

2002 |

| 1. Hewlett-Packard |

1. Hewlett-Packard |

| 2. National Semiconductor

|

2. Intel |

| 3. Intel |

3. Cisco b |

| 4. Memorex |

4. Sun b |

| 5. Varian |

5. Solectron |

| 6. Environtech a |

6. Oracle |

| 7. Ampex |

7. Agilent b |

| 8. Raychem a |

8. Applied Materials |

| 9. Amdahl a |

9. Apple |

| 10. Tymshare a |

10. Seagate Technology |

| 11. AMD |

11. AMD |

| 12. Rolm a |

12. Sanmina-SCI |

| 13. Four-Phase Systems a |

13. JDS Uniphase |

| 14. Cooper Lab a |

14. 3Com |

| 15. Intersil |

15. LSI Logic |

| 16. SRI International |

16. Maxtor b |

| 17. Spectra-Physics |

17. National Semiconductor |

| 18. American Microsystems a |

18. KLA Tencor |

| 19. Watkins-Johnson a |

19. Atmel b |

| 20. Qume a |

20. SGI |

| 21. Measurex a |

21. Bell Microproducts b |

| 22. Tandem a |

22. Siebel b |

| 23. Plantronic a |

23. Xilinx b |

| 24. Monolithic |

24. Maxim Integrated b |

| 25. URS |

25. Palm b |

| 26. Tab Products |

26. Lam Research |

| 27. Siliconix |

27. Quantum |

| 28. Dysan a |

28. Altera b |

| 29. Racal-Vadic a |

29. Electronic Arts b |

| 30. Triad Systems a |

30. Cypress Semiconductor b |

| 31. Xidex a |

31. Cadence Design b |

| 32. Avantek a |

32. Adobe Systems b |

| 33. Siltec a |

33. Intuit b |

| 34. Quadrex a |

34. Veritas Software b |

| 35. Coherent |

35. Novellus Systems b |

| 36. Verbatim |

36. Yahoo b |

| 37. Anderson-Jacobson a |

37. Network Appliance b |

| 38. Stanford Applied Engineering |

38. Integrated Device |

| 39. Acurex a |

39. Linear Technology |

| 40. Finnigan |

40. Symantec b |

NOTES: This table was compiled using 1982 and 2002 Dun & Bradstreet (D&B) Business Rankings data. Companies are ranked by sales.

a – No longer existed by 2002.

b – Did not exist before 1982.

In conclusion, Europe is characterized by a very Lamarckian entrepreneurial culture, promoting and supporting the established sectors, very much organized and structured for businesses, schools, unions, governments, banks, etc.. It excels in active innovation for engineers, in highly technical fields with great success in structured markets. Obviously, (page 164) “there is a real difficulty, which is the transfer of innovation in the entrepreneurial phase.” It means to (page 168) “take risks, foster a culture of trial / error” and not to penalize failure. “There is an urgent need to develop an entrepreneurial culture at all levels of our society: schools, colleges and universities, of course, but also in business and society in general.”

This is not about to be Lamarckian or Darwinian. “And remember that R&D is research and development, R for Darwin and D for Lamarck, the two steps of the Darwinian algorithm.” All the talent is in the balance between the two phases. (Page 170)

Here Picq might be wrong. Darwin and Lamarck should both be applied to the D and it may be where we have failed in Europe. We forgot Darwin needs to be in the development phase too.

Picq develops his concept of “bricolage” (page 174): “We have too long believed that the complexity of organisms depended on the number of genes.” … “In fact, the structures are simplified by successive integration during evolution (optimization) but they allow a variety of functions (plasticity).” (Page 175) “Animals and children are not Cartesian machines, we learn to walk, eat, especially for species of type K.” (Page 179) “In addition the machine Hydra which was never beaten by the best [chess] champions was beaten in 2005 by very good players – but not the great Masters – who used computers that were connected to standard sites and other players. This is Bricolage!” … “A combination of intelligent entities, but simpler and fed with external information is more effective than the best and most sophisticated machines with its programs, routines, software and internal databases.”

I could repeat here his warning on the misunderstanding of Darwinian theory that I put in the beginning. He added: “There is a grotesque conception of the war of all against all [in ecology as well as in innovation]” (page 185). “One must think competition not to eliminate, but with a strategy of coopetition.” … “This requires an open culture, with intricate collaborations.” … “Silicon Valley is the most paradigmatic model” while Sophia Antipolis is a juxtaposition of companies. “The territories and generally peripheral populations set innovations more easily and thus evolve more rapidly.” And again (page 236) “To be Darwinian does not mean to eliminate the other, but to exclude practices and models with deleterious effects on the economy and society as a whole. Darwinian theory has never been the law of the jungle, or the selfish individualism, or the war of all against all. Life is not a Rousseau-like world, but we live much less in the world of Hobbes. ”

One last anecdote: “In the early 1980s, IBM had been reluctant to enter the market of the computer. Big Blue has followed a K-strategy with great expertise on large computer systems. Then the management decided to “isolate” a small group of very creative engineers, without the constraints of the usual processes. This led to the IBM-PC, a perfect example of rapid innovation by genetic drift in a population of small size and placed in the periphery.” This is exactly the illustration of the Innovator’s Dilemma theory from Clayton Christensen.

I’ll let you read his conclusion on why humankind went to Australia. And I have not taken the time to talk about his description of gazelles, antelopes, buffaloes and other elephants, or his defense of a Small Business Act for France (or Europe). Picq might be criticized for inaccuracies, misstatements, a little fast and simple description of a complex situation, but it would be wrong to stop at this, because this is a book extremely stimulating not to say enthusiastic.