So I asked Gates: “What do you think of the idea that we’re not seeing as much innovation and scientific progress as we should? That the rate of progress has stalled?”

“Oh you guys are full of shit. Total shit…”

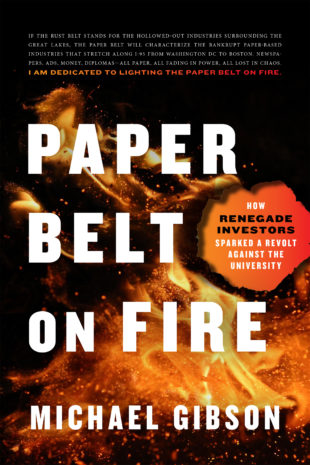

This is how Bill Gates reacts on page XI of Paper Belt on Fire, How Renegade Investors Sparked a Revolt against the University to author Michael Gibson’s ideas that he describes in detail in his recent book.

The book is both exciting and frustrating, convincing sometimes and unnerving at others. But let me mention what was questioning [to me].

The central thesis of the book has four parts. The first is that science, know-how, and wisdom are the source of almost all that is good: higher living standards; longer, healthier lives; thriving communities; dazzling cities; blue skies; profound philosophies; the flourishing of the arts; and all the rest of it.

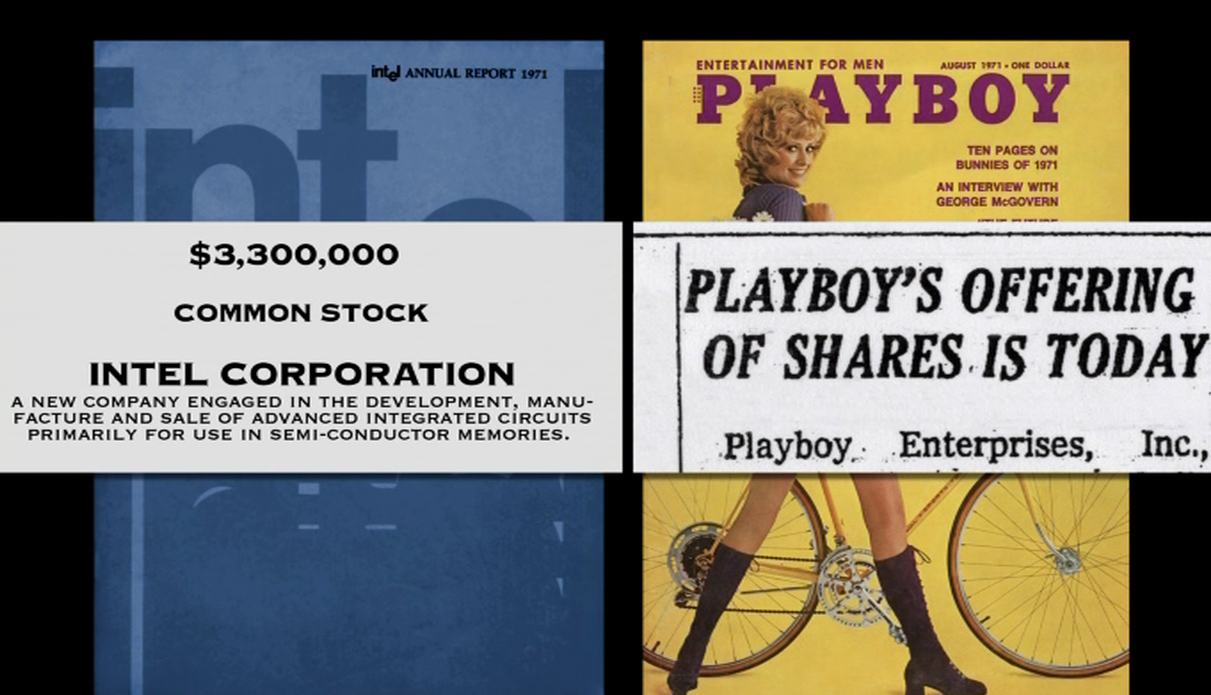

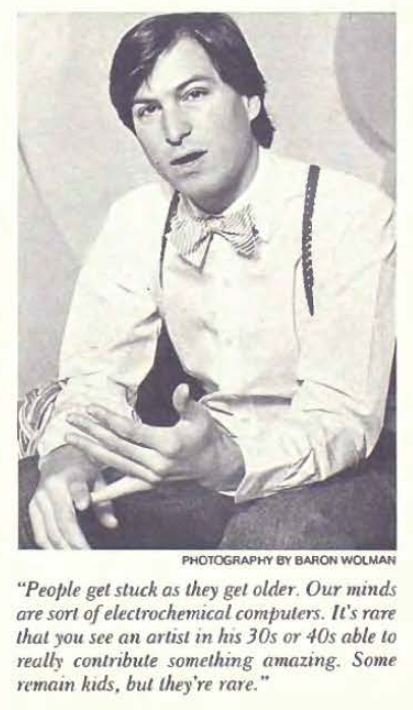

The second is that the rate of progress in science, know-how, and wisdom, has flattened for far too long. We have not been making scientific, technological, or philosophical progress at anything close to the rate we’ve needed to since about 1971. (Computers and smart phones notwithstanding.)

The third claim is that the complete and utter failure of our education, from K-12 up through Harvard, is a case in point of this stagnation. We are not very good at educating people, and we have not improved student learning all that much in more than a generation, despite spending three to four times as much per student at any grade. Our lack of progress in knowing how to improve student outcomes has greatly contributed to the decline in creativity in just about every field.

The last, chief point is that the fate of our civilization depends upon replacing or reforming our unreliable and corrupted institutions, which include both the local public school and the entire Ivy League. My colleagues and I are trying to trailblaze one path in the field of education. We might be misguided in our methods, but our diagnosis is correct. [Pages XIX-XX]

What are the traits of great founders? [Pages 89-96]

Edge control, crawl-walk-run, hyperfluency, emotional depth & resilience, a sustaining motivation, the alpha-gamma tensive brilliance, egoless ambition, and Friday-night-Dyson-sphere.

Edge control: a willingness day after day, to defy the boundary between the known and the unknown, order and disorder, vision and hubris.

Crawl-walk-run: a founding team needs to have the smarts to build what they are going to build. […] The best way to screen for these traits is to see them at play in the wild. It takes some time to see their evolution.

Hyperfluency: the best founders have the charm of a huckster and the rigor of a physicist. […] They speak with fluent competence.

Emotional depth & resilience: the founders of a company have to have the social and emotional intelligence to make hires, work with customers, raise money from investors, and gel with co-founders. The complexity of this total effort is incredibly demanding and emotionally exhausting.

Tensive brilliance: what we’ve noticed is that creative people tend to have a unity born of variety. That unity may have a strong tension to it, as it tries to reconcile opposites. Insider yet outsider, familiar yet foreign, strange, but not a stranger, young in age but older in mind, a member of an institution but a social outcast – all kind of polarities lend themselves to dynamism. This is in part, I believe, why immigrants and first-generation citizens show a strong productivity for entrepreneurship. They are the same, but different.

Egoless ambition: on the one side there is an intense commitment to do great things. But on the other side is an element of detachment, a footloose, untroubled attitude that treats triumph and disaster just the same.

Friday-night-Dyson-sphere: the physicist Freeman Dyson once imagined a sphere of light-absorbing material surrounding our entire solar system on its periphery. One of the most electrifying moments for us is when a team convinces us, through a series of plausible steps backed by evidence, that they are capable of growing a lemonade stand into a company that builds Dyson Spheres. What’s more, it’s clear this is the thing they’d rather be tinkering on during a Friday night when all the cool kids are out partying.

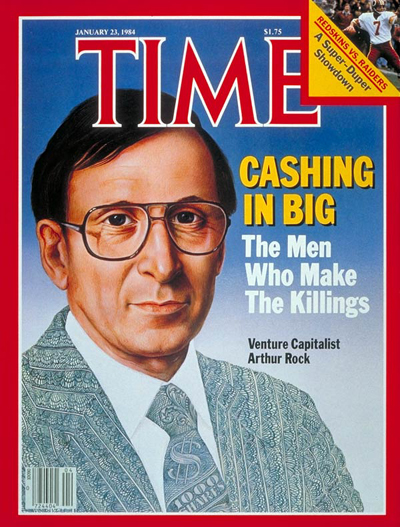

The 1517 fund [1]

“We’re named after the year Martin Luther nailed his ninety-five theses to a church door in a tiny German town. That began a revolution, the Protestant Reformation. But it all started because he was protesting against the sale of a piece of paper called an indulgence. In 1517, the church was saying this expensive piece of paper could save your soul. In 2015, universities are selling another expensive piece of paper, the diploma, saying it’s the only way to save your soul. Well, it was bullshit then. And it’s bullshit now.” [Page 144]

For one thing, most venture capital funds fail. Blind folded monkeys throwing darts to pick stocks would perform better than the investor who picked the average venture capital fund. The median VC returns about 1.6 percent less than if someone just put their money in an index-tracking mutual fund. [Page 147]

To accelerate progress, we need young people working at the frontiers of knowledge sooner than they have in the past. They also need greater freedom. What that means is institutions that trust them to take risks and demonstrate some edge control with their research. We must hold it as a fairly predictable law of creativity that the unknown must always pass through the stranger before we can understand it.

Universities have served this research function in the past and will continue to do so. But they are plagued by four realities. The first is the slow speed of a formal, credential-based education. It takes four years to earn a bachelor’s degree and then another seven or eight to earn a PhD. Second, universities have become hives of groupthink. Third, grant-giving is driven by prestige, credibility, and a cover-your-ass mentality. Fourth, the incentives of academic institutions reward shrewd political calculation, incrementalism, short-term horizons, and a status hierarchy in which demonstrating loyalty earns more reward than advancing knowledge. [Page 261-2]

About education

The good news is that two cheap, relatively easy to use methods stand out as the most effective at boosting student performance: practice testing and distributed practice. Distributed practice is when students establish and stick to a consistent schedule of practice over time. (Its antithesis is cramming.) Practice is not mere repetition, but a deliberate effort to improve performance in the Goldilocks zone where success is neither too easily gained, nor the challenge too hard. Self-resting as a technique should not be confused with high stakes standardized testing but instead as a way of frequently probing the edge of knowledge in a field. […] Consistent self-testing and distributed practice are the most effective learning techniques, but they are also the most painful, as both of these strategies require discipline, energy, and individual effort.

Then there are the more intangible questions that require our attention. How can we encourage students to pursue the truth, independent of other people’s approval? How do we teach civil disobedience, training our young to fight for what’s right? Or how to practice delayed gratification for worthy long-term goals? Are these even possible to teach? No one has bothered to ask. [Pages 301-302]

If you are not unnerved and still intrigued, then you may read his final chapter around James Stockdale and David Foster Wallace.

Now what I found unnerving is the huge difference between exceptions, anecdotes in a system and a social statistical problem. I will only quote a great and rather unknown novel: Les Thibault by Roger Martin du Gard: « Je vous avoue que je ne sais plus très bien ce que je lui ai conseillé. J’ai dû – naturellement – l’engager à ne pas abandonner l’école. Pour des êtres de sa trempe, notre enseignement est, somme toute, inoffensif : ils savent choisir, d’instinct ; ils ont – comment dirais-je – une désinvolture de bonne race, qui ne se laisse pas mettre en lisière. L’Ecole n’est fatale qu’aux timides et aux scrupuleux. Au reste, il m’a paru qu’il venait me consulter pour la forme et que sa résolution était prise. C’est justement l’indice d’une vocation, qu’elle soit impérieuse. C’est bon signe qu’un adolescent soit en révolte, par nature, contre tout. Ceux de mes élèves, qui sont arrivés à quelque chose étaient tous de ces indociles. » [Page 754 of volume 1, collection folio and this gives in English “I confess to you that I no longer really know what I advised him. I had to – naturally – urge him not to drop out of the School. For beings of his caliber, our teaching is, after all, harmless: they know how to choose, instinctively; they have – how shall I put it – a good-natured casualness, which does not allow itself to be put on the edge. The School is fatal only to the timid and the scrupulous. Besides, it seemed to me that he came to consult me for the form and that his resolution was taken. It is precisely the sign of a vocation, that it be imperious. It is a good sign that a teenager is in revolt, by nature, against everything. Those of my students who achieved something were all of these rebellious ones.”]

[1] I did not mention until now and will in this footnote that Gibson, in a way, belongs to the PayPal mafia of anarcho-libertarians that include Peter Thiel and Elon Musk. Gibson co-managed the Thiel Fellowship and now the 1517 fund. There are notable Fellows as shown on Wikipedia. Now quoting Peter Thiel did the recipients did better than what he dreamed of: “We wanted flying cars, we got 140 characters instead” or did they really answer his famous question “What’s something you believe to be true that the rest of the world thinks is false?” [Page 60]