The issue is discussed in the June 2015 issue of Horizons, the research magazine of the Swiss National Science Foundation, to which I was asked to participate.

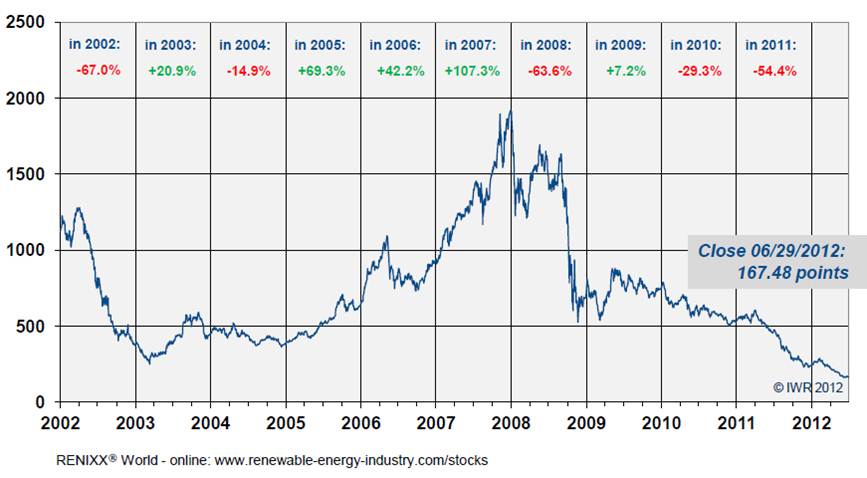

Dozens of startups are launched every year in Switzerland to commercialize the results scientific research funded in large part by the State. Should universities that have supported them become rich in case of commercial success?

Yes, says the politician Jean-François Steiert.

Over the last twenty years, about a thousand companies, mostly small, contributed to the success of Switzerland. The majority of them are successful, although investors, inclined to take risks, are rare in Switzerland as compared for example to the United States. Most of the time the spin-offs are supported by taxpayer money, in terms of infrastructure, social networks, scholarships or coaching services. The objective of this kind of public investment is primarily to encourage employment and research.

With the support from public funds, these innovations generate through sales or patents significant benefits in the order of tens or hundreds of millions of francs. The public, as an investor, must be able to require a portion of those profits. Not to allow the State or the universities to get rich, but to reinvest these funds in fostering the next generation of researchers.

At a time when the Confederation and the cantons implement programs of savings due to exaggerated tax cuts, additional funds must be generated in this way and support young researchers in the economic development of their innovations.

“The public, as an investor, must be able to require a portion of the profit.” Jean-François Steiert

When the sale of patents is concerned, it is not a question of aiming for the maximum return, nor of making profits with a unique key. Universities need flexibility to optimize the return. On the one hand, we need the creation and management of start-ups to remain attractive. On the other, one must reinvest adequately in the next generation of researchers.

What is lacking today is transparency. If universities want to maintain the confidence of the taxpayer, they must declare how much money is generated by their successful startups. This information, they owe it to the taxpayer who, rightly, wants to know if her money is well invested in research, a key area for Switzerland.

Jean-François Steiert (PS) is a member of the National Council since 2007 and member of the Commission for Science, Education and Culture.

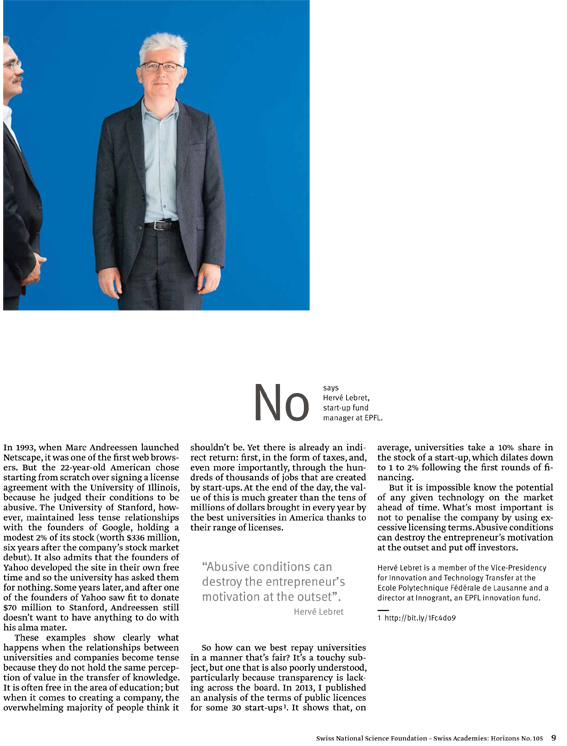

No replies Hervé Lebret, manager of an EPFL investment fund.

When Marc Andreessen launched Netscape in 1993, one of the first Web browsers, the 22-year old American chose to start from scratch rather than sign a license with the University of Illinois, the conditions of which he considered abusive. Instead, Stanford University had less tensed relations with the founders of Google, taking a modest 2% stake (which become $336 million six years later at the company IPO). The same university asked nothing to Yahoo! as it considered that the founders had developed the web ite on their spare time. A few years later, one of the founders of Yahoo! made a gift of $ 70 million to Stanford – whereas Andreessen does not want to hear anything about his alma mater.

These examples show how the relationships between universities and corporations can worsen when they do not share the same perception of the value of a knowledge transfer. The latter is often free when it comes to education; but when it comes to entrepreneurship, the overwhelming majority of people think it should not be. Nevertheless, an indirect return already exists: first in the form of taxes and, more importantly, through the hundreds of thousands of jobs created by start-ups. Their value is ultimately much higher than the tens of millions of dollars reported each year by the best American universities from their licenses.

“Abusive conditions can discourage the entrepreneur even before she starts.” Hervé Lebret

How then to define a fair retribution for universities? The subject is sensitive, but poorly understood, partly because of a lack of transparency from the different actors. In 2013, I published an analysis of the terms of public licenses from thirty startups [1]. It shows that universities hold on average a 10% equity stake at the creation of the start-up, which is diluted to 1-2% after the first financing rounds.

It is impossible to know in advance the commercial potential of a technology. We must first ensure that it is not penalized by excessive license terms. Abusive conditions can discourage the entrepreneur even before she starts and discourage investors. And thus kill the goose in the bud.

[1] http://bit.ly/lebrstart

Hervé Lebret is a member of the Vice President for Innovation and Technology Transfer at EPFL and manager of the Innogrants, an innovation fund from EPFL in Lausanne.