When a young colleague of mine (thanks Amine!) mentioned a paper entitled The Science of Startups: The Impact of Founder Personalities on Company Success, I was intrigued not to say interested. You can find the version published on Nature here and the one on arXiv there.

When I look back on the 741 articles of this blog, 118 are tagged with founders, coming only second after Silicon Valley. Most of them deal with facts and figures but 38 mention the term personality. For example:

– Knowledge, skills and personality of entrepreneurs (dated March 2021) https://www.startup-book.com/2021/03/19/knowledge-skills-and-personality-of-entrepreneurs/ where it is claimed “There’s an entrepreneurial character.”

– The Founder’s Dilemmas – The Answer is “It depends!” (dated December 2013) https://www.startup-book.com/2013/12/12/the-founders-dilemmas-the-answer-is-it-depends/ where the claim is “There are no real pattern in becoming a founder (age, experience, childhood influences, personality, family status, economic status), however early influences and natural motivations seem to be important.”

– Larry Page and Peter Thiel – 2 (different?) Icons of Silicon Valley (date October 2021) https://www.startup-book.com/2021/10/30/larry-page-and-peter-thiel-2 -différentes-icônes-de-la-silicon-valley/

and I would advise anyone interested in the topic to read the book Founders at Work. I put my long notes about this great book at the end of this post.

This new article is long and a little complex. So I just took notes directly in the text and paste them here. But the article is worth reading if you have the time and interested.

Attention has increasingly considered internal factors relating to the firm’s founding team, including their previous experiences and failures, their centrality in a global network of other founders and investors as well as the team’s size. […] The effects of founders’ personalities on the success of new ventures are mainly unknown. […] Here we show that founder personality traits are a significant feature of a firm’s ultimate success.

[…]

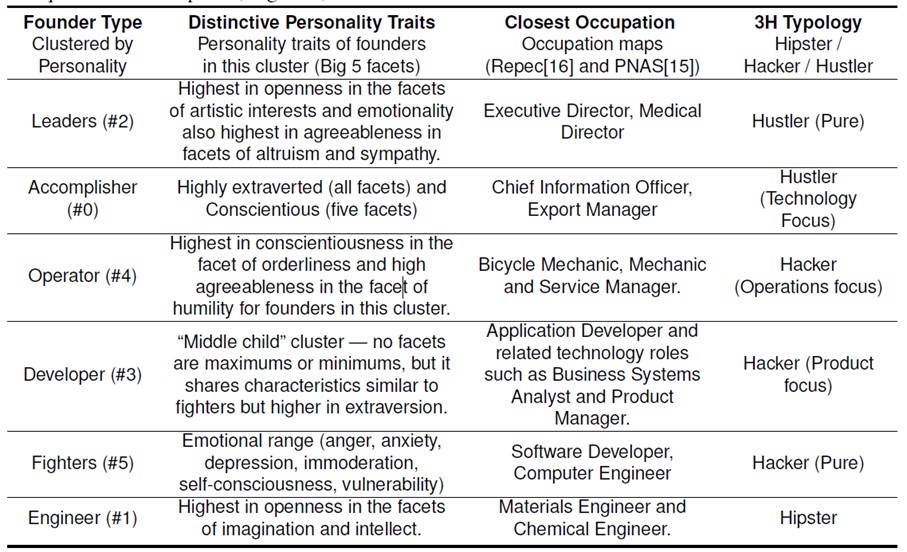

Key personality facets that distinguish successful entrepreneurs include a preference for variety, novelty and starting new things (openness to adventure), like being the centre of attention (lower levels of modesty) and being exuberant (higher activity levels). However, we do not find one Founder-type personality; instead, six different personality types appear, with startups founded by a “Hipster, Hacker and Hustler” being twice as likely to succeed. Our results also demonstrate the benefits of larger, personality-diverse teams in startups.

[…]

In this article, we analyse a variety of firm-level, founder-level and founder-team-level determinants of the success of startups, which are by their very nature experimental, high risk and likely to fail.

Firstly, we examine a range of firm-level determinants of startup success, including location, industry and age of startup to explore to what extent these factors are associated with success. Then building on our previous occupation-personality fit research, we use a large collection of public data on startup companies from Crunchbase to examine the detailed personality profiles of founders.

[…]

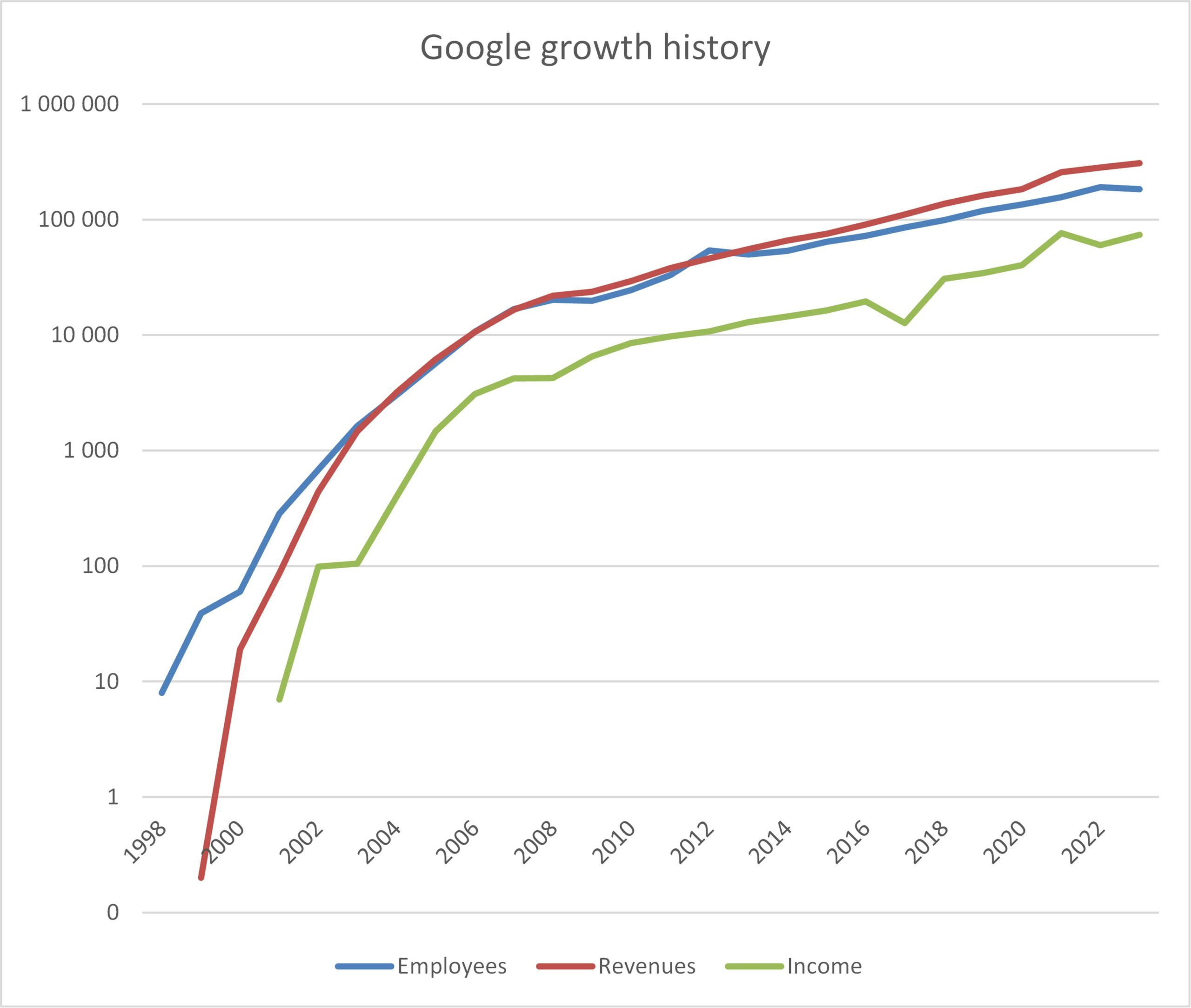

Firm-Level Factors of Startup Success. On a country level, chances for success are highest in the US, Japan, West Europe, and Scandinavian countries. Firms from the payment and software industries have high chances of success. Chances of success are positively related to a firm’s maturity, with firms that are seven years or older having higher chances of success.

[…]

Does the combination of founders and their personalities play a role in startup success, and is there any evidence to support the commonly held view in the venture capital investment community that startups require three types of founders: a Hacker, a Hustler and a Hipster?

[…]

In technology, the categorical roles of Hackers (skillful computer programmers and developers) and Hustlers (entrepreneurial leaders able to win over customers and investors to new

products and ideas) have been around for decades, with […] oppositional tension. For example, when Steve Jobs announced he would take medical leave from Apple in January 2009, Mat “Wilto” Marquis described him as a hacker and a hustler in a well-wishing tweet. However, the first use of Hacker and Hustler in conjunction with Hipster in the context of the putative startup founder dream was coined by influential venture capitalist Elias Bizannes in 2011. It was then popularised in 2012 by an address at the influential technology conference South by Southwest by Rei Inamoto and in a subsequent Forbes article “The Dream Team: Hipster, Hacker, and Hustler”. Hipster is a broad term used to describe members of an urban subculture in many cities in the US and other countries who are design conscious and favour non-mainstream fashions, trendy foods and alternative music. Bizannes co-opted the term to reflect what he perceived was the increasing need for successful startups to have a founder with design-savvy, aesthetic imagination and insider knowledge (Hipster) in addition to the traditional roles of someone good at selling things (Hustler) and creating technology products (Hacker).

[…]

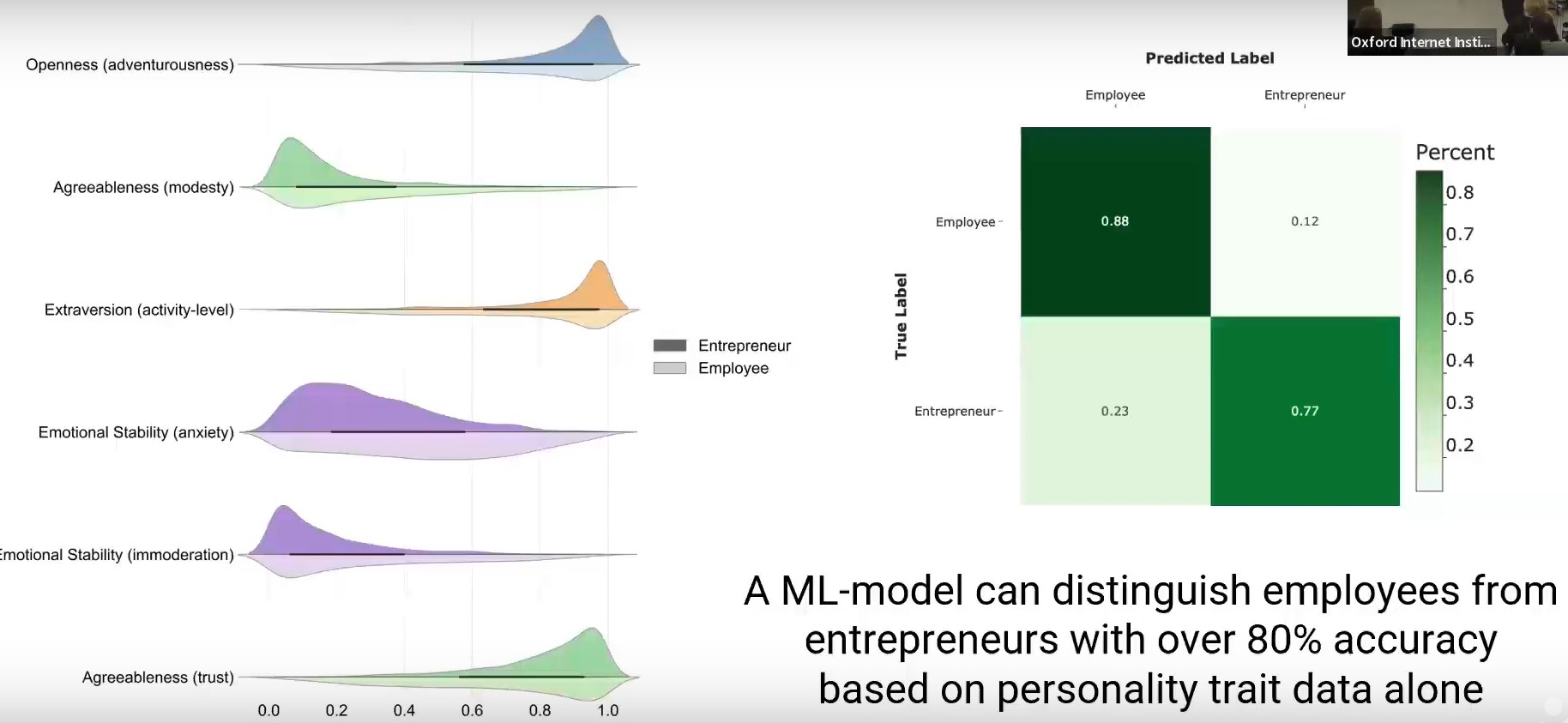

While recent research has demonstrated that many employees in the same occupations share similar personality traits, being a startup founder is not a conventional job. we inferred the personality traits across 30 dimensions (Big 5 facets) of a large global sample (n=4.4k) of successful startup founders.

[…]

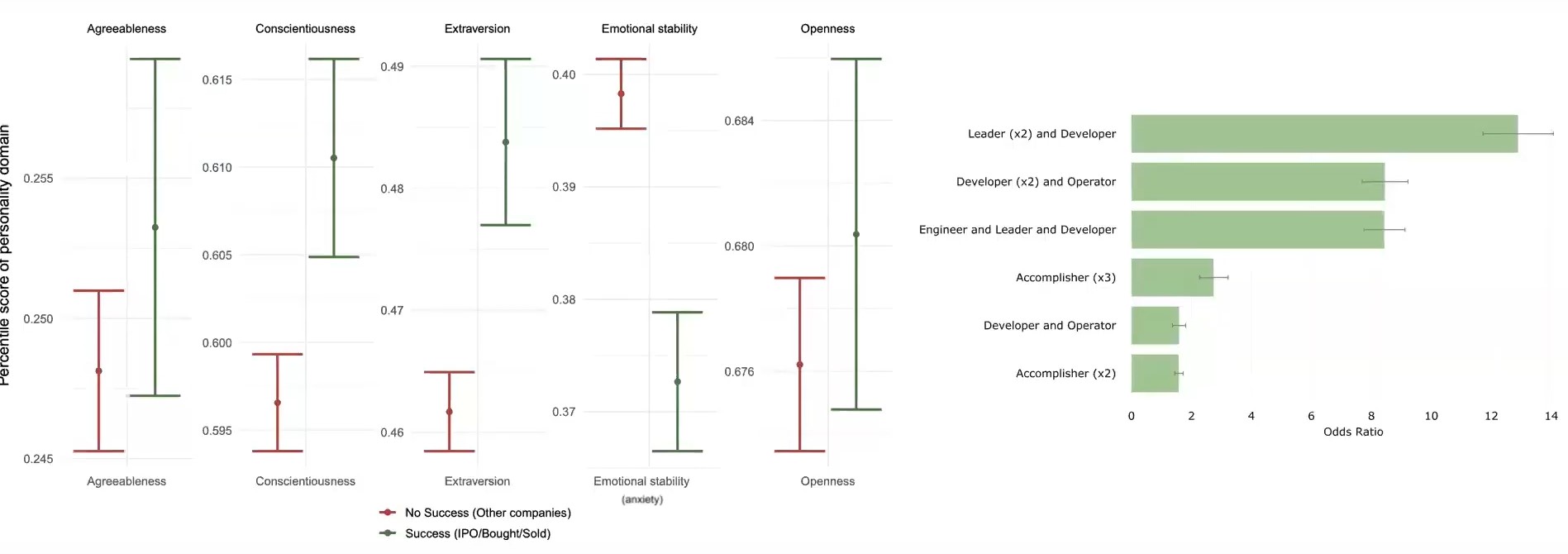

Using two samples together: Successful Entrepreneurs and Successful Employees (unlikely to be founders), we trained and tested a machine learning random forest classifier to distinguish and classify entrepreneurs from employees and vice-versa using inferred personality vectors alone. As a result, we found we could correctly predict Entrepreneurs with 77% accuracy and Employees with 88% accuracy. Thus, based on personality information alone, we correctly predict all unseen new samples with 82.5% accuracy.

[…]

Adventurousness— the key feature

We explored in greater detail which personality features are the most important in distinguishing successful entrepreneurs from successful employees and found that the subdomain or facet of

Adventurousness within the Big 5 Domain of Openness was both significant and had the largest effect size. The facet of Modesty within the Big 5 Domain of Agreeableness and Activity Level within the Big 5 Domain of Extraversion was the subsequent most considerable effect. All thirty dimensions of the Big 5 facet were found to be significantly different in their distribution, with ten features having large effect sizes. […] Adventurousness in the Big 5 framework is defined as the preference for variety, novelty and starting new things

[…]

Six types of startup founders

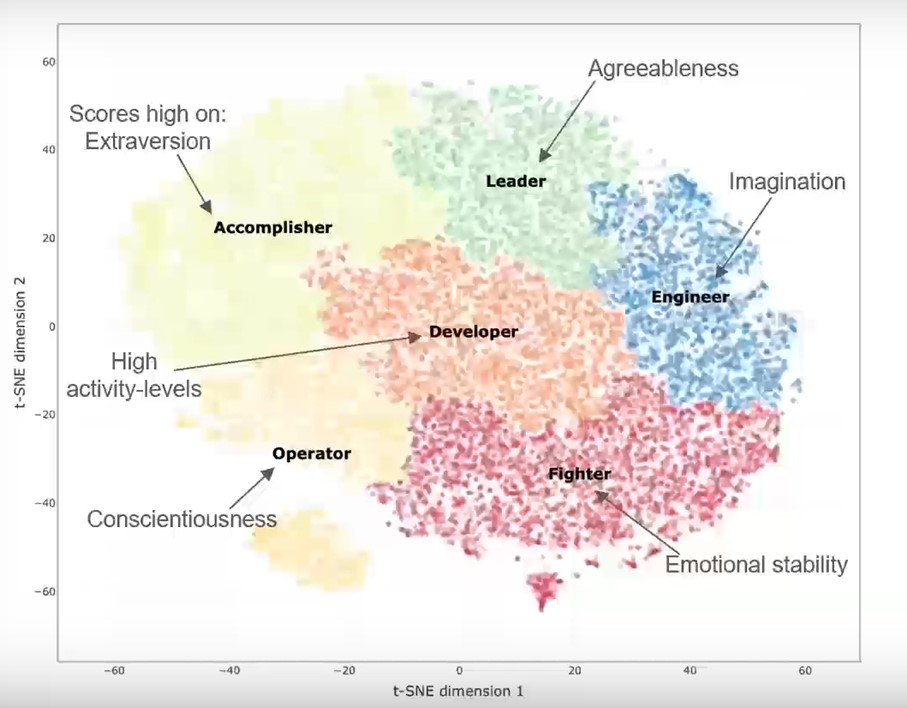

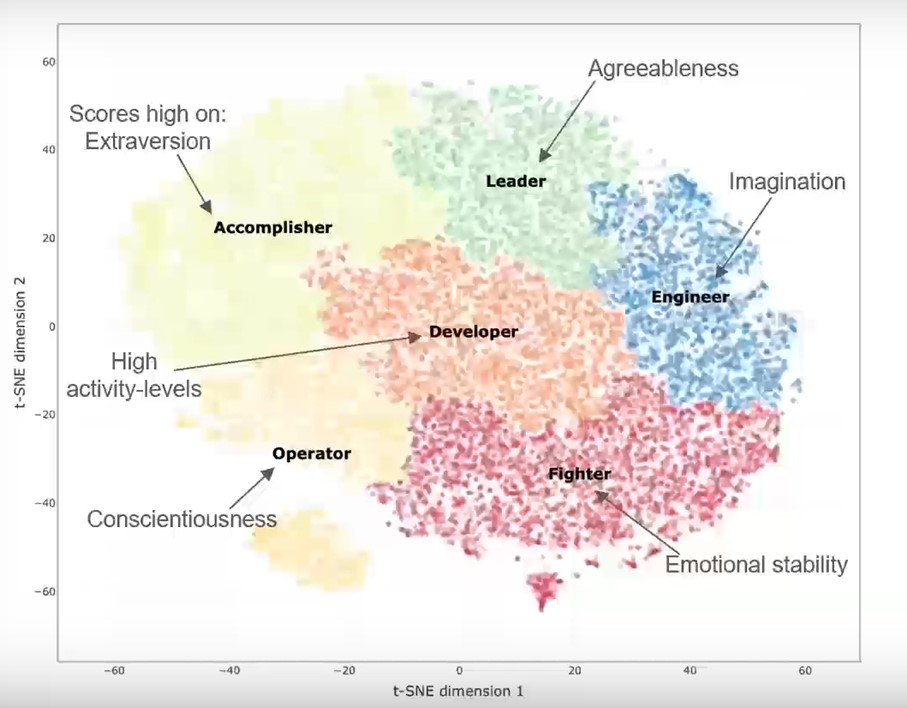

Once we understood that startup founders have distinctive personality features that are different from regular employees, we explored whether there are distinct types of personalities among startup founders.

[…]

We discovered clear clustering tendencies in the data. Then, once we established the founder data clusters, we used agglomerative hierarchical clustering; a “bottom-up” clustering technique that initially treats each observation as an individual cluster and then merges them to create a hierarchy of possible cluster schemes with differing numbers of groups. And lastly, we identified the optimum number of clusters based on the outcome of four different clustering performance measurements. We found that the optimum number of clusters of startup founders based on their personality features is six (labelled #0 through to #5).

[…]

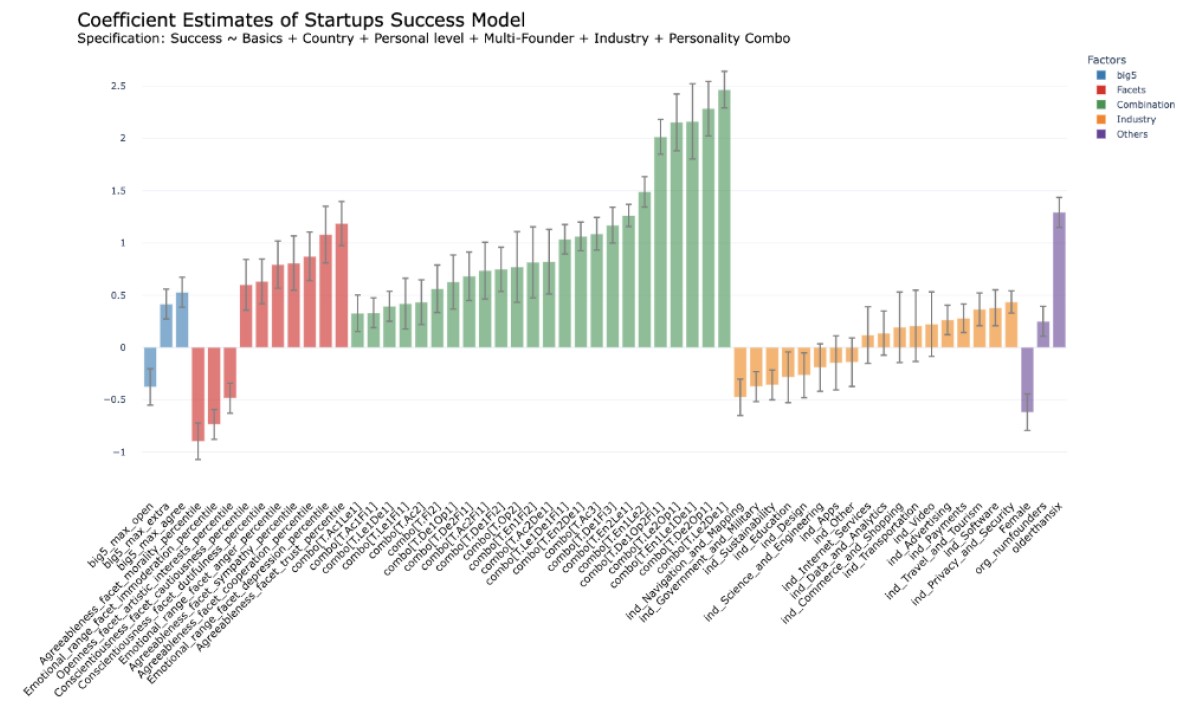

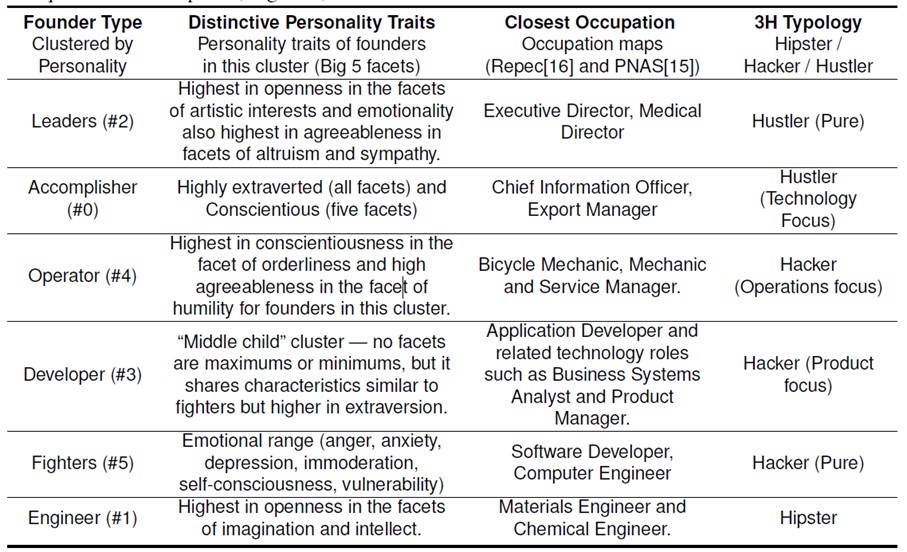

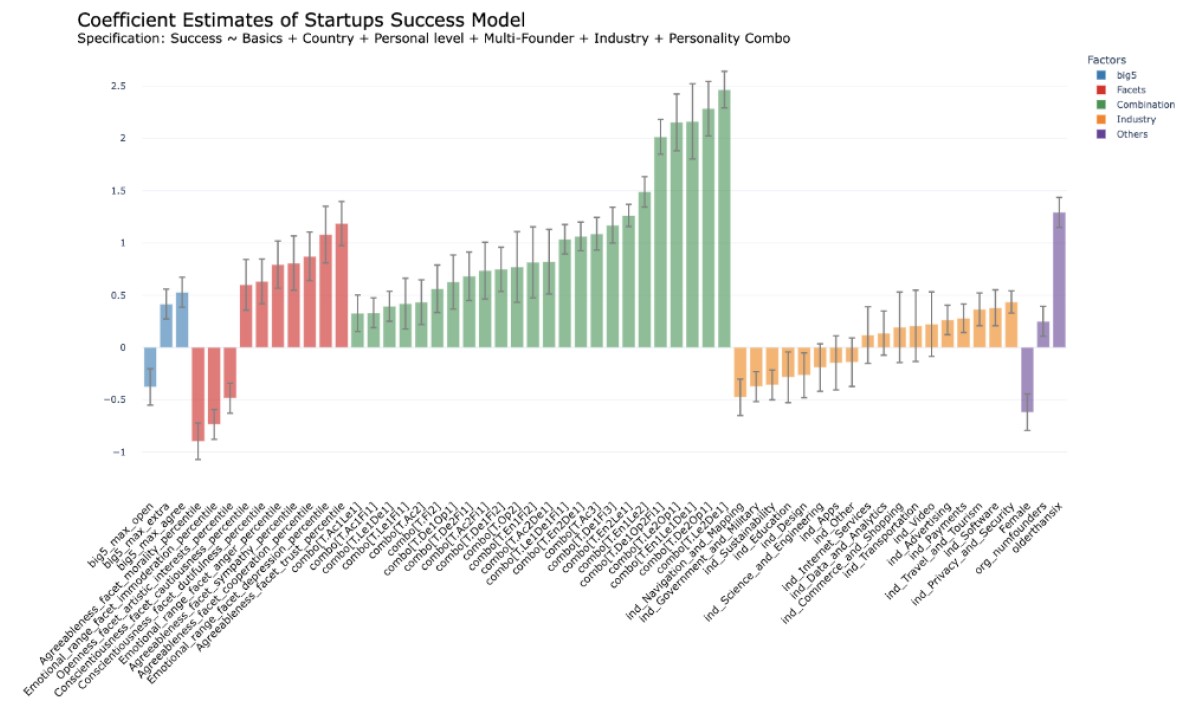

Together, these six different types of startup founders represent a framework we call the FOALED model of founder types—an acronym of Fighters, Operators, Accomplishers, Leaders, Engineers and Developers. Each founder Personality-Type has its distinct facet footprint. Also, we observe a central core of correlated features that are high for all types of entrepreneurs, including intellect, adventurousness and activity level.

[…]

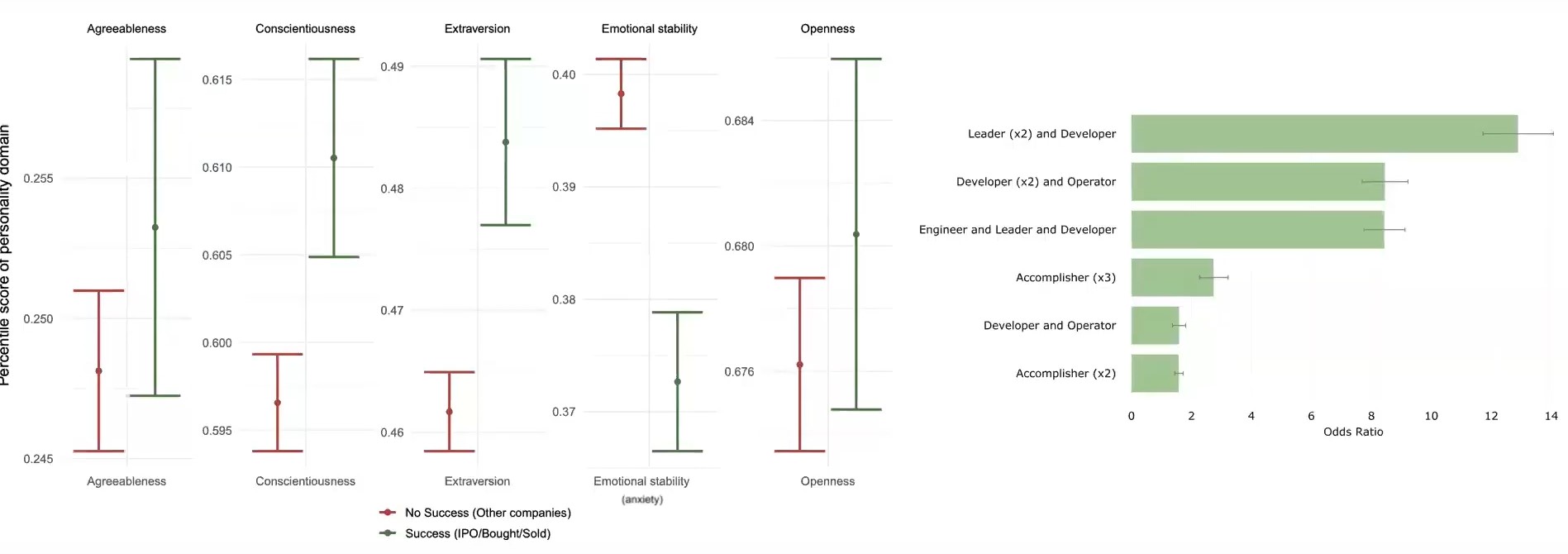

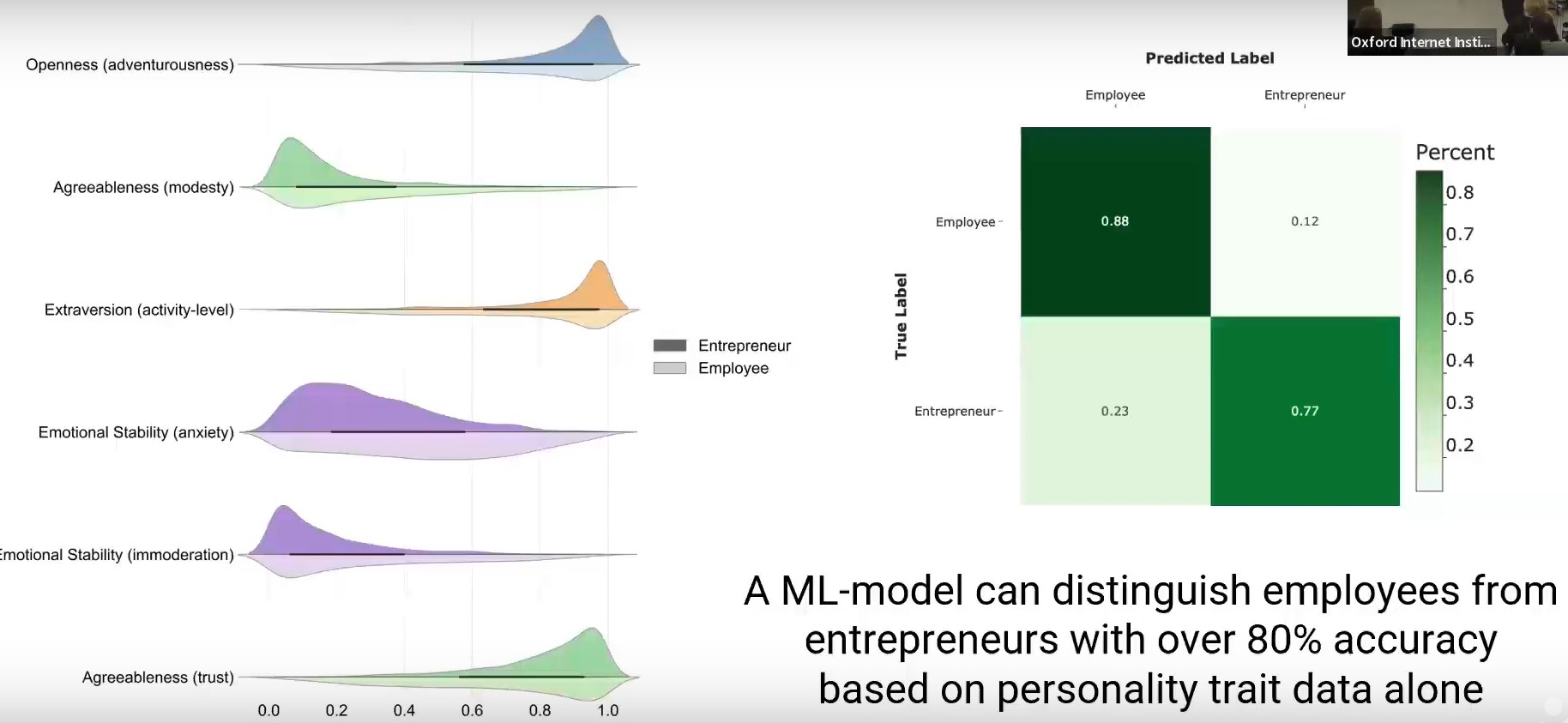

By analysis of the six types of startup founders in our FOALED model within the broader Occupation-Personality landscape, we identify three types to be characterised as types of Hackers (Fighters, Operators and Developers) and two as Hustlers (Accomplishers and Leaders). The remaining type is different in personality to both Hackers and Hustlers. It is more of a subject matter expert whose insider field knowledge and problem-solving design strengths can be seen as a type of Hipster (Engineer). When we subsequently explored the combinations of personality types among founders and their relationship to the probability of the firm’s success, adjusted for a range of other factors in a multi-factorial analysis, we found significantly increased chances of startup success for Hipster, Hacker and Hustler foundation teams.

[…]

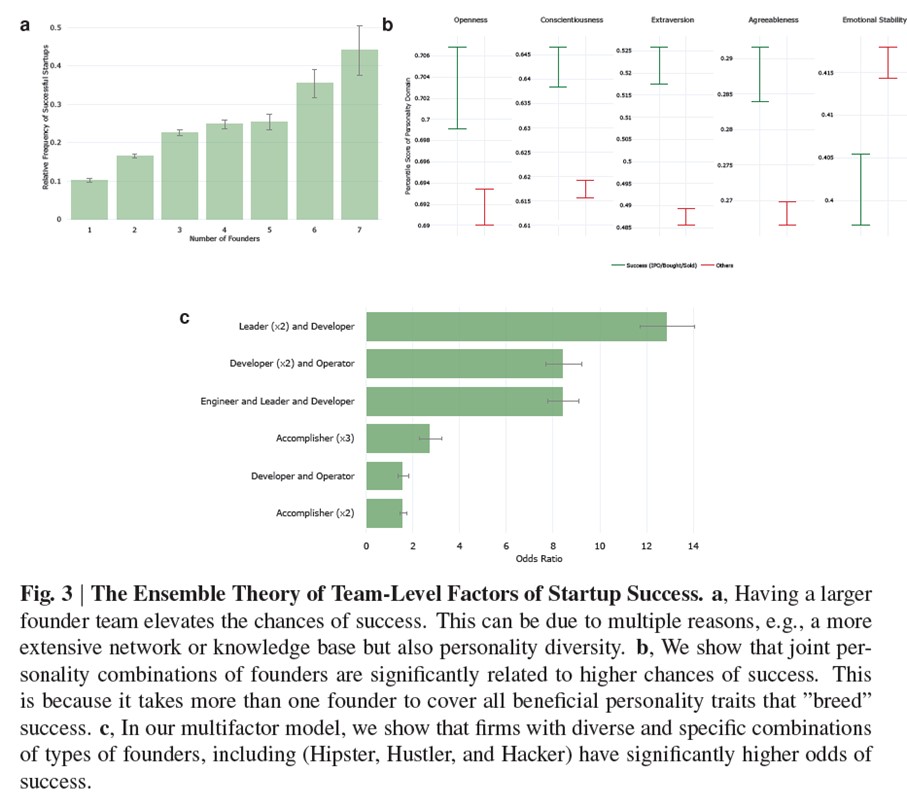

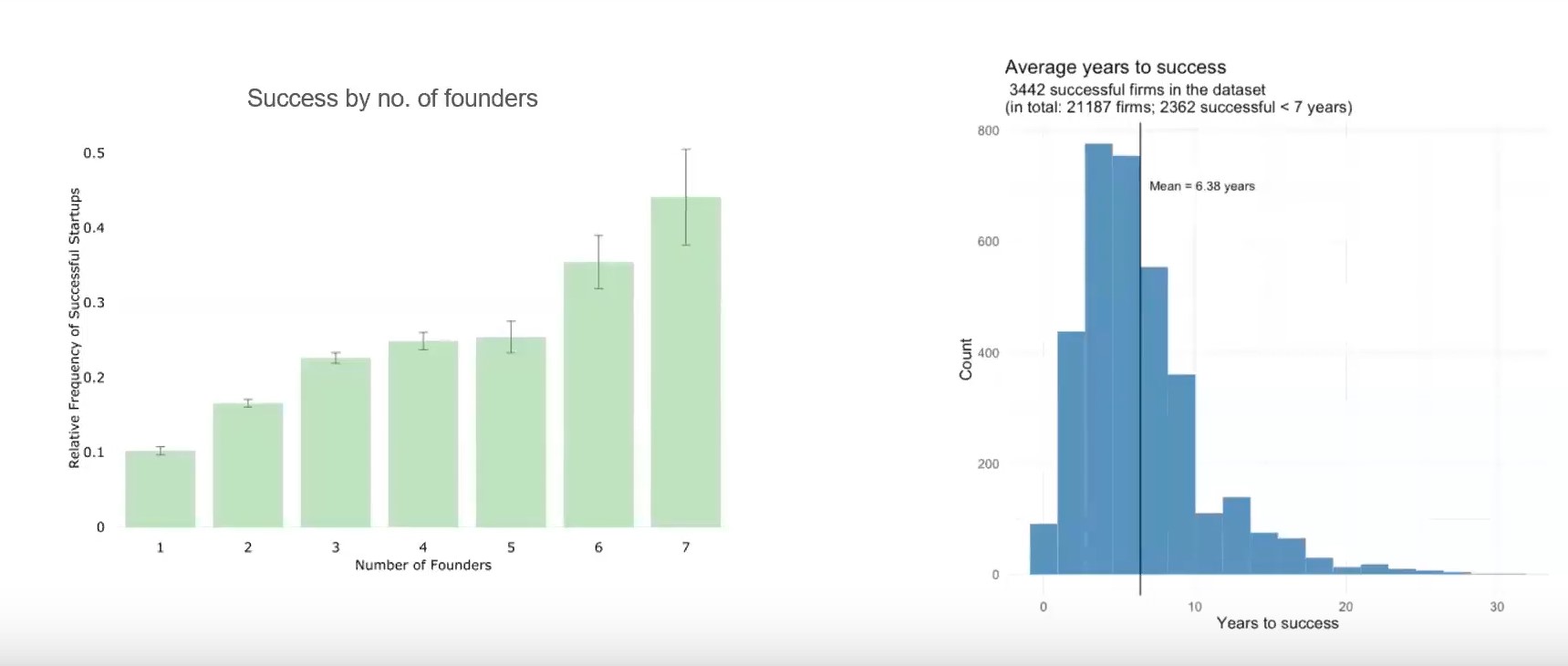

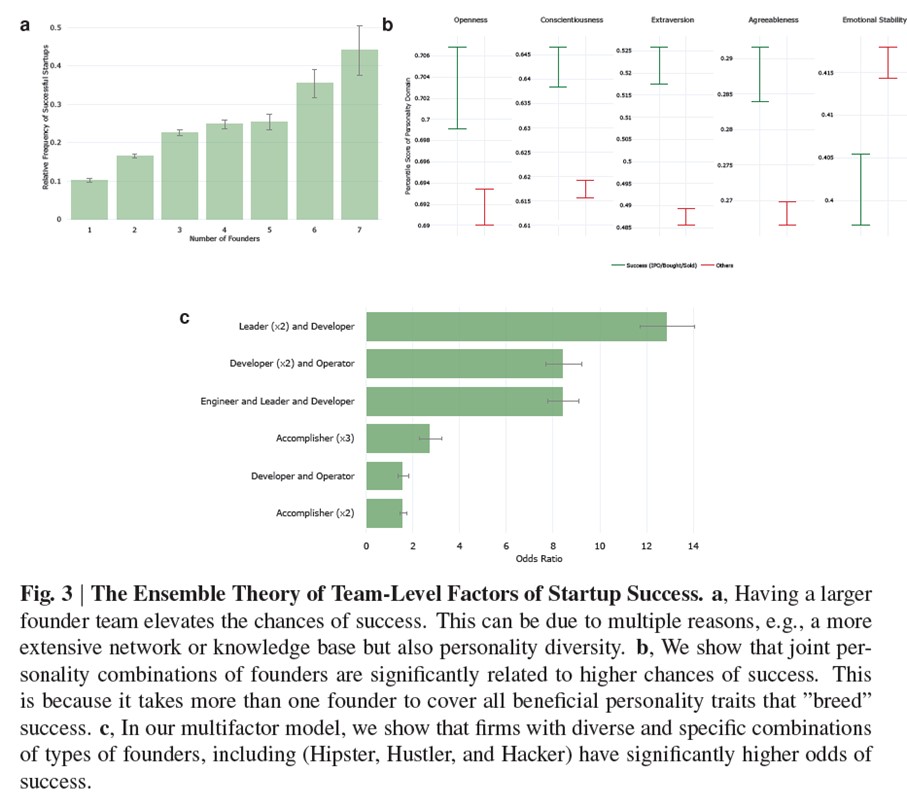

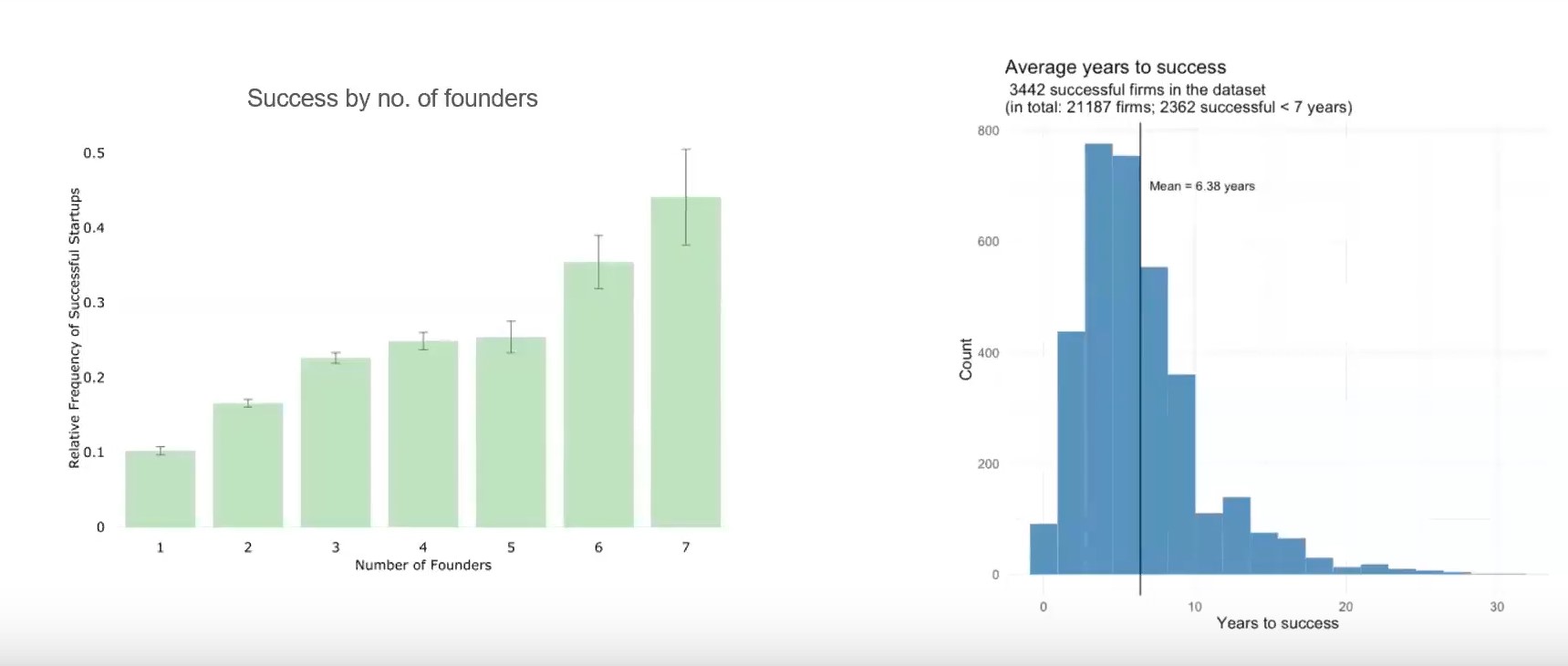

Our modelling shows firms with multiple founders are more likely to succeed, as illustrated in Fig. 3a), which shows firms with three or more founders are more than twice as likely to succeed as solo-founded. The benefits of larger and more personality-diverse foundation teams can be seen in the apparent differences between successful and unsuccessful firms based on their combined Big 5 personality team footprints, illustrated in Figure 3b). Here maximum values within each startup for each Big 5 trait for any of its cofounders are mapped, and the spread of these between sucessful firms — those who have IPOed, been acquired or acquired another firm and the other firms are shown. […] We found that ten combinations of founders with different personality types were significantly correlated with greater chances of startup success when accounting for other variables in the model. The coefficient of each of these factors is illustrated concerning other features that were also found to be significantly associated with success in Figure 3c.

[…]

We have learnt through this research that there is not one type of ideal “entrepreneurial” personality but six different types. Many successful startups have multiple co-founders with a combination of these different personality types. Startups are, to a large extent, a team sport; as such, diversity and complementarity of personalities matter in the foundation team. It has an outsized impact on the company’s likelihood of success. While all startups are high risk, the risk becomes lower with more founders, particularly if they have distinct personality traits. Our work demonstrates the benefits of diversity among the founding team of startups. Greater awareness of these benefits may help create more resilient startups capable of more significant innovation and impact.

More figures

Is there anything to conclude? Are the authors right or wrong? Can this be used for prediction? I do not know. The authors admit themselves there are biases in their research (it is based on the Twitter accounts of the founders…). I missed the element of the relationships between founders and I am a little skeptikal that more founders is better beginning with 3 or 4. My experience is that a team of 2 founders is ideal (you could chekc my long series of studies on startup data here. But who am I say this today ? What is certain is that the article is interesting and its ambtion to be praised !

Founders at Work - May08