Rarely have I read two articles giving a vision as close apparently of the challenges and issues of the future of the planet as I’ll mention in a moment. I say apparently, because behind some consistencies about a confident vision of the future, lie fairly fundamental differences about the challenges.

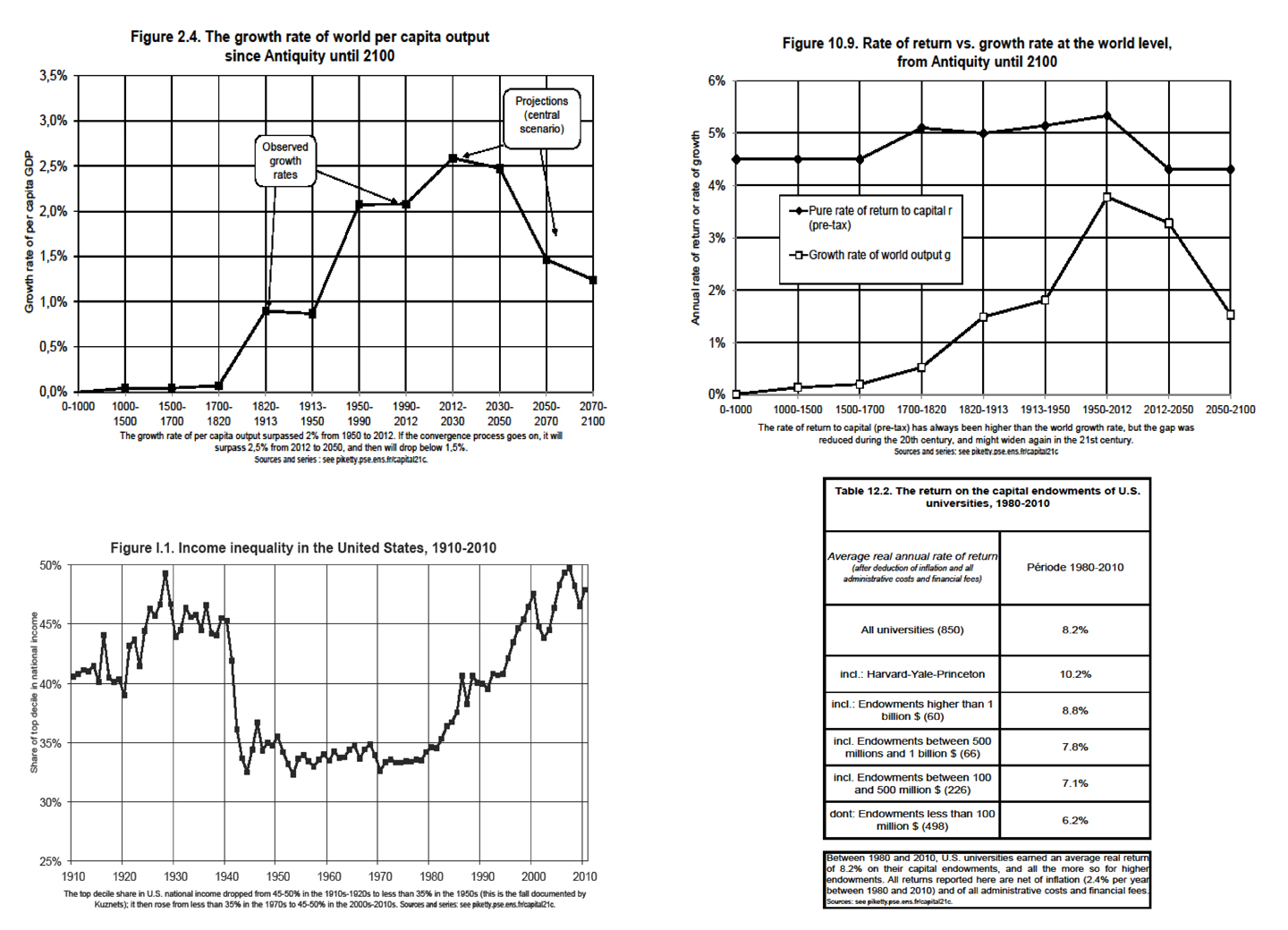

But I will allow myself a digression before commenting these tow articles. A third article was published on a very different subject in the paper edition the New Yorker dated Oct. 10, 2016 – again apparently as it deals about the past and the present! It is entitled He’s Back. This article reminded me that my two most important readings in 2016 (and perhaps in the 21st century) are those that I mentioned in the post Has the world gone crazy? Maybe…, namely the tremendous Capital in the 21st Century by Thomas Piketty and the no less remarkable In the disruption – How not to go crazy? by Bernard Stiegler. I need to give the title of the digital edition that might hopefully inspire you to discover Karl Marx, Yesterday and Today – The nineteenth-century philosopher’s ideas may help us to understand the economic and political inequality of our time.

Back to the point that motivates this post. Barack Obama has just published in The Economist a short text in which he describes the challenges ahead. This is a brilliant article. It also creates a certain mystery for me around the American president. Is he very well surrounded by knowledgeable advisors and / or has he become interested so deeply in topics to the point of finding the time to write (I should say to describe) himself the world’s complexity. An absolute must-read: The Way Ahead.

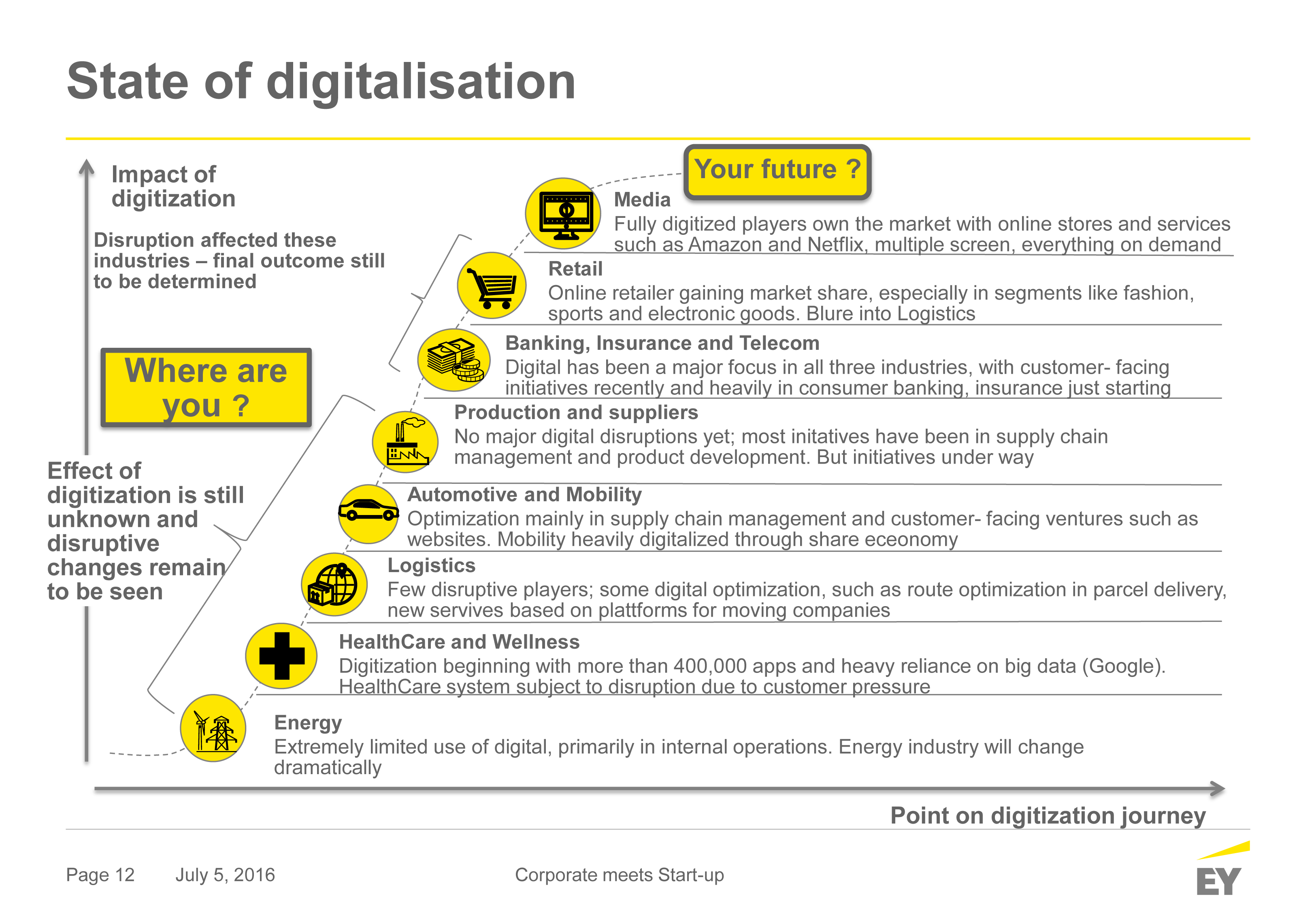

In comparison, Adding a Zero in the same Oct. 10 New Yorker – entitled in the electronic version Sam Altman’s Manifest Destiny with however an identical subtitle Is the head of Y Combinator fixing the world, or try trying to take over Silicon Valley? This very long article describes perfectly the reasons why we can equally love and hate Silicon Valley. It is a Pharmakon (both a remedy and a poison according Stiegler’s words). I encourage you to read it too, but your priority should go to reading Barack Obama.

I’ll try to explain myself. Obama has tried a lot and has not been so successful, but there has a consistency in his acts, I think. In The Economist, he wrote: “Fully restoring faith in an economy where hardworking Americans can get ahead requires addressing four major structural challenges: boosting productivity growth, combating rising inequality, ensuring that everyone who wants a job can get one and building a resilient economy that’s primed for future growth.” Obama is an optimist and a moderate. All but a revolutionary. There is a beautiful sentence in the middle of the article: “The presidency is a relay race, requiring each of us to do our part to bring the country closer to its highest aspirations.” The highest aspirations. I sincerely believe that is why Obama deserved the Nobel Peace Prize despite all the difficulties of his task.

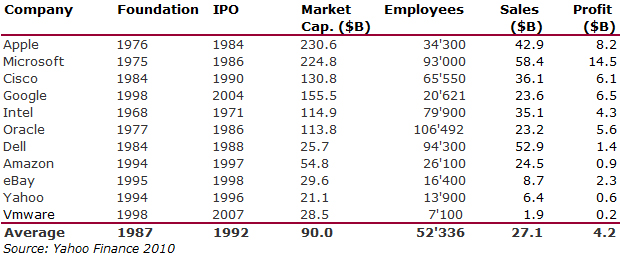

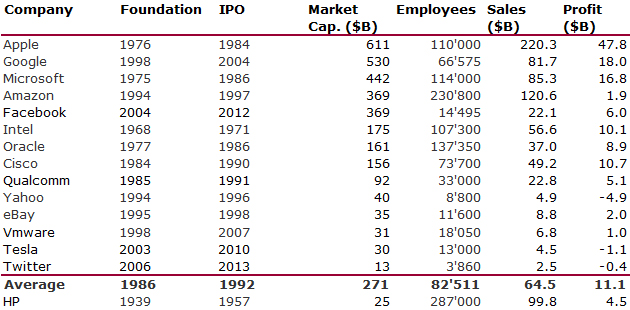

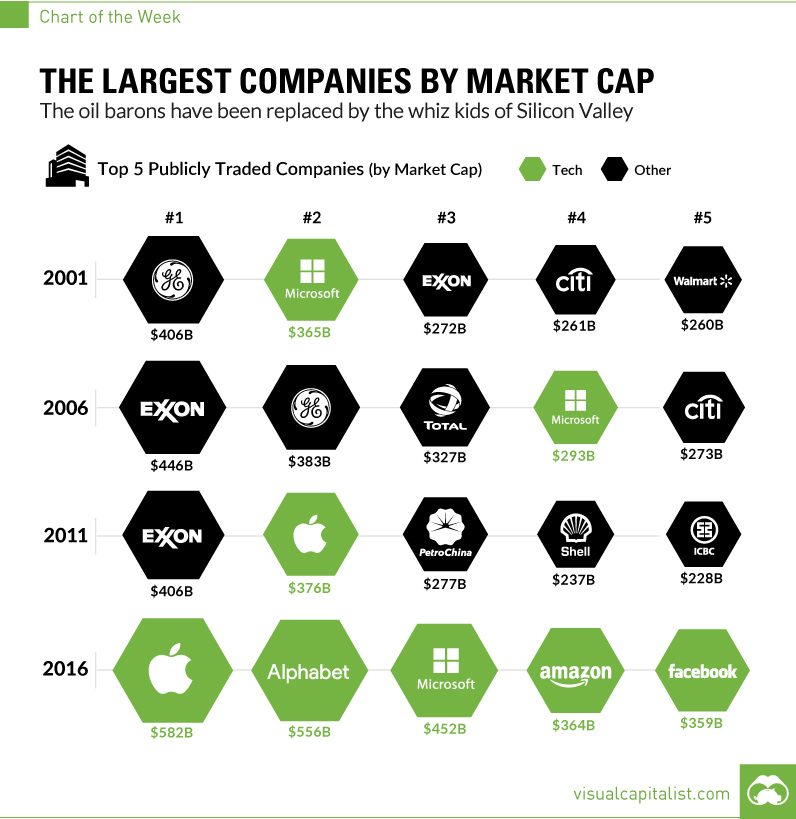

Silicon Valley has the same optimism and the same belief in technological progress and well-being that it brings (or may bring). Growth is a mantra. Sam Altman is no exception to the rule. Here are some examples: “We had limited our projected revenue to thirty million dollars,” Chesky [the founder and CEO of Airbnb] said. “Sam said, ‘Take all the “M”s and make them “B”s.’ ” Altman recalls telling them, “Either you don’t believe everything you said in the rest of the deck, or you’re ashamed, or I can’t do math.” [Page 71] then a little further “It is one of the rarer mistakes to make, trying to be too lean,” Altman said, “Don’t worry about a competitor until they’re beating you in the market,” … “Competitors are one of the last monsters that haunt your dreams.”… “Always think about adding one more zero to whatever you’re doing, but never think beyond that.” [Page 75]

Illustration by R. Kikuo Johnson

Illustration by R. Kikuo Johnson

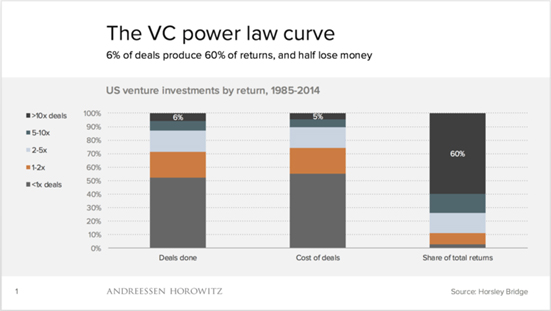

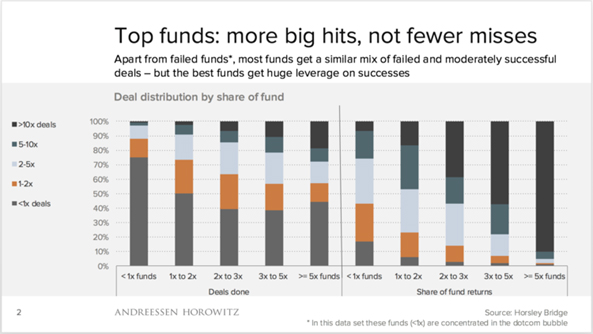

Clearly risk taking steps accordingly: In a class that Altman taught at Stanford in 2014, he remarked that the formula for estimating a startup’s chance of success is “something like Idea times Product times Execution times Team times Luck, where Luck is a random number between zero and ten thousand.” [Page 70] The strategy of accelerators such as Y Combinator looks pretty simple: “What we ask of startups is very simple but very hard to do. One, make something people want”—a phrase of Graham’s, which is emblazoned on gray T-shirts for the founders—“and, two, all you should be doing is talking to your customers and building stuff.” [Page 73] The result of this strategy lies in the performance of these acceleration mechanisms: A 2012 study of North American accelerators found that almost half of them had failed to produce a single startup that went on to raise venture funding. While a few accelerators, such as Tech Stars and 500 Startups, have a handful of alumni worth hundreds of millions of dollars, Y Combinator has graduates worth at least a billion—and it has eleven of them. [Page 71] but Altman is dissatisfied: Venture capitalists believe that their returns follow a “power law,” by which ninety per cent of their profits come from one or two companies. This means that they secretly hope the other startups in their portfolio fail fast, rather than staggering onward as resource-consuming “zombies.” Altman pointed out that only a fifth of YC companies have failed, and said, “We should be taking crazier risks, so that our failure rate would be as high as ninety per cent. [Page 83]

“Under Sam, the level of YC’s ambition has gone up 10x.” Paul Graham, who was leaving soon after the dinner for a sabbatical year in England, told me that Altman, by precipitating progress in “curing cancer, fusion, supersonic airliners, A.I.,” was trying to comprehensively revise the way we live: “I think his goal is to make the whole future.” [Page 70] Recently, YC began planning a pilot project to test the feasibility of building its own experimental city. It would lie somewhere in America, or perhaps abroad, and would be optimized for technological solutions: it might, for instance, permit only self-driving cars. “It could be a college town built out of YC, the university of the future,” Altman said. “A hundred thousand acres, fifty to a hundred thousand residents. We crowdfund the infrastructure and establish a new and affordable way of living around concepts like ‘No one can ever make money off of real estate.’ ” He emphasized that it was just an idea—but he was already looking at potential sites. You could imagine this metropolis as an exemplary post-human city-state, run on A.I. — a twenty-first-century Athens — or as a gated community for the élite, a fortress against the coming chaos. [Page 83] YC’s optimism goes very far: “We’re good at screening out assholes,” Graham told me. “In fact, we’re better at screening out assholes than losers. […] Graham wrote an essay, “Mean People Fail,” in which—ignoring such possible counterexamples as Jeff Bezos and Larry Ellison—he declared that “being mean makes you stupid” and discourages good people from working for you. Thus, in startups, “people with a desire to improve the world have a natural advantage.” Win-win. [Page 73]

Altman is not devoid of social conscience, well not quite. “If you believe that all human lives are equally valuable, and you also believe that 99.5 per cent of lives will take place in the future, we should spend all our time thinking about the future.” [He looks at] the consequences of innovation as a systems question. The immediate challenge is that computers could put most of us out of work. Altman’s fix is YC Research’s Basic Income project, a five-year study, scheduled to begin in 2017, of an old idea that’s suddenly in vogue: giving everyone enough money to live on. … YC will give as many as a thousand people in Oakland an annual sum, probably between twelve thousand and twenty-four thousand dollars. [Page 81] But the conclusion of the article is perhaps the most important sentence of the whole article, which brings us back to Obama’s moderation. Comparing himself to another wildly ambitious project creator, Altman says, “At the end of his life, he did also say that it should all be sunk to the bottom of the ocean. There’s something worth thinking about in there.”

Ultimately, Obama, Altman, Marx, Piketty and Stiegler all have the same faith in the future and progress and the same concern about the growing inequalities. Altman seems to be the only one (together with many people in Silicon Valley) to believe that disruptions and revolutions will solve everything, while the others see their destructive features and prefer a moderate and progressive evolution. Over the years, I tend to prefer moderation too…

PS: if you would not have enough reading, then continue with the series of interviews President Obama gave to Wired: Now Is the Greatest Time to Be Alive.