I just read an excellent interview of Lita Nelsen who has recently retired as head of MIT’s Technology Licensing Office. You should read the full Exit Interview: Lita Nelsen on MIT Tech Transfer, Startups & Culture. I was used to say that MIT was more conservative than Stanford just like the Boston Area has been known to be more conservtaive than California, but things change. So let me just mention a few extracts.

Lita Nelsen (Formerly head of MIT Technology Licensing Office)

About patents:

Patents are needed because the whole idea is if you’re going to get somebody to invest a lot of time and a lot of money, if you succeed you don’t want the other guy, the bigger guy, saying, “Well, thank you very much. Now that you’ve shown the way, get out of the way.” We are primarily using patents as an incentive for investment.

About universities having an investment fund:

[The Technology Licensing Office helps] start about 25 or 30 companies a year. God knows how many [other companies started on campus] go out the back door. No one fund could put that amount of sweat equity into all of them. Now imagine we have MIT’s fund, and I invest in company A, but don’t have the resources to do B, or maybe not C. Then I go with C to [an outside venture capital firm] and say, “How would you like my leftovers?” There’s a negative selection bias there for what we don’t invest in. So, better to let a level playing field for anybody who wants to play.

But one thing any institution doing it has to decide is, are we primarily in it for return on investment? Or are we primarily in it for getting companies started that wouldn’t otherwise get started? You usually get a mixed message if you ask people which it is. And as everybody knows, when you get mixed missions, things get very hard to manage.

About equity in licensing:

How much equity does the Technology Licensing Office usually take when it spins out a company? Usually in the lower single digits, maybe a little higher if you have a software spinout. And it’s common shares.

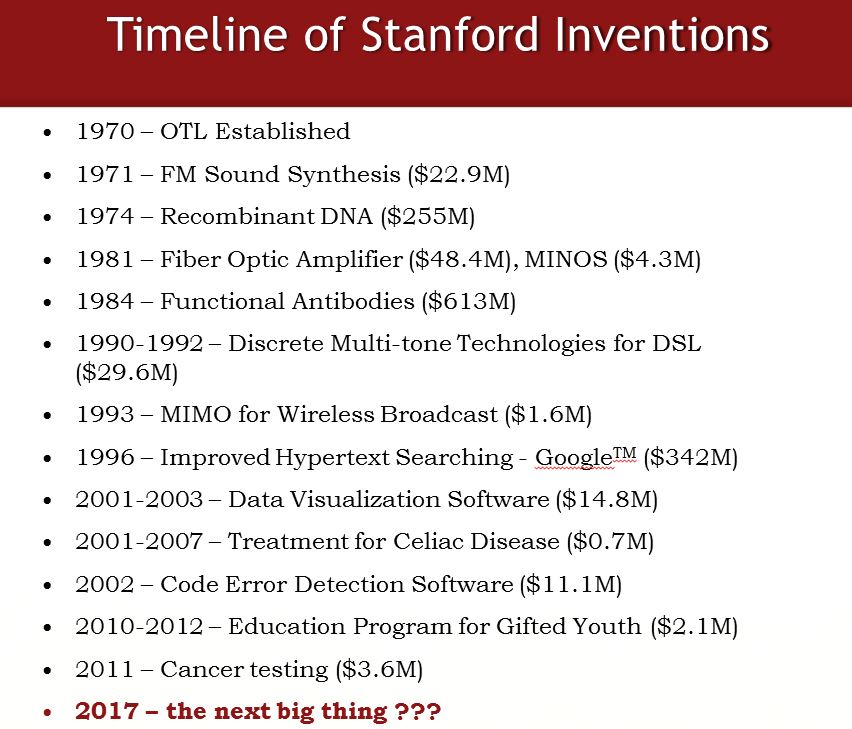

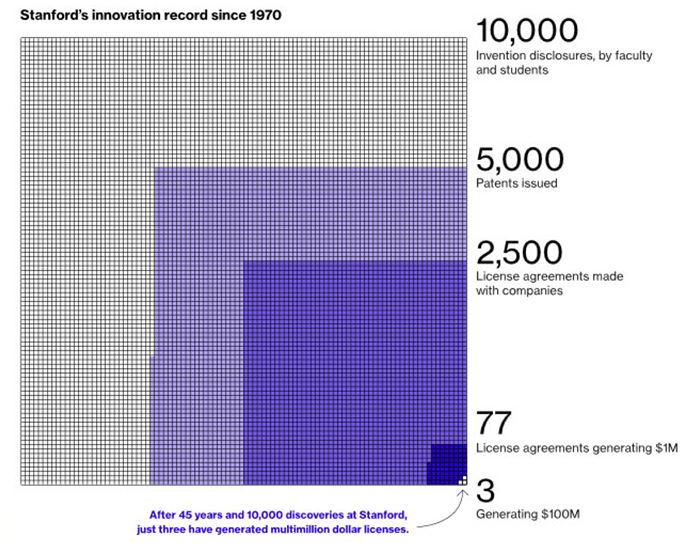

If it’s research-intensive stuff—biotech, things that take multiple rounds of funding—[our stake] usually gets demoted down to [tiny] portions. You make a little money; you don’t make a lot. Except in cases when the Wall Street bubble is totally irrational. Even nationwide, you can show that tech transfer is, at best, a lottery if you want to make an ability to influence [a university’s financial position]. The primary winners—not 100 percent of them, but damn close—are single pharmaceuticals. Because if a pharmaceutical hits the market, it’s going to be in the multi-billon dollar [range]. The equity is seldom worth a lot, unless of course you can follow up with preferred investments. But that’s not what we’re in the business of doing. Any university that counts on its tech transfer to make a significant change in its finances is statistically going to be in trouble.

About accelerators:

“Does MIT have an incubator?” And my classic answer has been, “Yes, it’s called the city of Cambridge.”

The problem with accelerators is the definition has become as broad and varied as incubators, which range from science parks to little projects within universities, so you don’t know what the word means until you dig in. But some of them are putting money into product development. Some of them are venture funds expecting ROI. Some of them are [funded] through donations, as we did with Deshpande and Harvard did with their accelerator.

It’s going to be interesting to look at the mechanisms that people are trying. Because the problem is there: How do we get from the stage of which the university has done its research and maybe even gotten on the cover of Science magazine, to where somebody is going to invest in that ripening process before it actually turns into true product development, short-term product development? How do you get from the petri dish to full-scale clinical trials? You’ve got to get pretty far along before pharma’s going to do that for you. So people are looking both within universities and outside of universities as to how you fill the gap.

About teaching entrepreneurship:

now MIT, with its emphasis on innovation, is investing officially in training students in innovation and entrepreneurship, along with, not separate from, their intense technical educations. It’s not “you go and learn how to be an entrepreneur,” it’s you learn biology or chemistry or electrical engineering or computer science, but you also learn how entrepreneurship and innovation and moving technology out into the marketplace works—rather than having to learn that after you graduate.