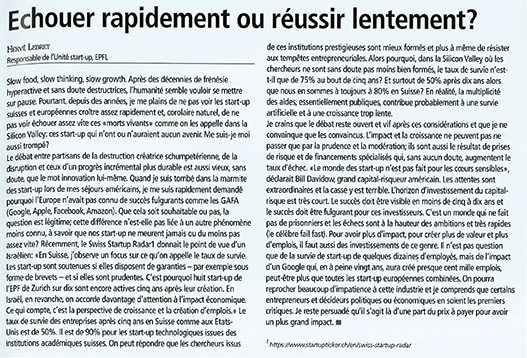

While looking at old files, I found a letter, written by a family member in october 1993. At the time, I was living in California. I read it again, loved it so much for personal reasons but also found it so farseeing that I decided to share it here. Hopefully some of you will like it. If you read French, go to the French page, if not forgive my awkward translation…

Tell me, my good friends, what is America? The roughness of the confines, this impossible frontier where humans find themselves by violence stripped of lies, where the truth is revealed? The old southern lands, so carnal, so indolent, so cruel? The devastating wind gusts and hurricanes in the business that are moving people across the country? The Blacks, the Yellows, the Darks, the Goldens and the Indians who open casinos in their reservations, just to take some power from the Whites? The Indians are a faded dream, like Route 66, like the Rocky Mountain train. In Europe, paradoxically, we experience America in a visual mode more than in writing or thinking. Everyone does not read Tocqueville, but then, who is Tocqueville’s successor? There remains the image. Fake images where violence and melodrama reigned, between popcorn and ice cream, the tanned men of westerns, statues of dust and wind, the dazzling comedians of the musicals, Miles Davies, head down, dark glasses, emaciated face, pushing on his trumpet in a corner, excited suffragettes and delusional sodomites. The true and the false mix, merge. The memory stutters. De Niro continues to return to his companions, the steelmakers, on a rainy night, climbing a muddy street lined with small pavilions, in the blue-gray, monstrous and motley decor of foundries; Kennedy collapses again in the back of his big convertible car, under the bewildered look of Jackie; and I still go around Long Island and Brooklyn to approach the arrogant challenge of the Manhattan Towers. Or I fly high mountains, deserts, lakes, endless plains, where the eye hangs, staking the immensity, pressed and tight clusters of skyscrapers, mounds of the day, monuments of glass and concrete in the silence of nights, built to the glory of which unknown dead god.

I watch sometimes CBS Evening News, I see people worry about everything and anything, to the obsession. Haunted by cancer, cellulite, poisoned milk, fast weight loss, tobacco smoke, the nimble hands of men and the eyes of others. I wonder: what has become of proud America? Or did it ever exist only in presidents’ speeches on the state of the Union? What is America? Thoreau and the transcendentalists, Charles Ives, the musician insurer, who has captured better than anyone else the roar of the choral society, the feast and the provincial slowness, the immensity of the lands and the simplicity of the beings? Or Blacks who are perhaps the most American of Americans since they have really lost their roots (Africa is not a place, but a myth and rhythms while emigrants still have families, which in Sicily, which in Korea, which in Mexico, which in Ireland)? Or this “melting pot” that does not mix, but that unites because in the manner of the feudal society, the membership is aimed at people, the sworn faith, requests the individual to the noblest of itself? (Perhaps we should not laugh too much at the Bibles deposited in the hotel rooms, which symbolize the direct and intimate relationship that Protestants establish between man and his creator. Transposed, we perceive the direct relationship, transcendent of all the administrative, legal, institutional mediations that unite the American man to America: God is America. Like God, would it be inaccessible to our intellect?) We find everything, apparently in America. Would it be the store of the creator, La Samaritaine of eternity? Is America out of time? Alice in the land of rubble wanders among abandoned silos, deserted factories, discarded jerrycans, worn tires, rusted bodies, to discover in the spreading fields the unexpected, the surprising, the eternally new. America, pioneering and tired.

I say this to myself, but maybe I’m wrong. The ambiguous attitude that we Old Europeans have towards America is rather a parent-child relationship that combines ambition, hope, expectation and disappointment, surprise and misunderstanding, rapture and exasperation, tenderness and anger. Recognition, ignorance. A new being has come out of us, which prolongs us but which is not ourselves and whose destiny escapes us. America, America, the dream of the emigrant, but also in some way our dream to all of us. The new Jerusalem or the new Babylon. Something strikes, if one tries to fly over the centuries. The other side. The other side of the hills, the other side of the mountains. We are people of little witnesses, of limited horizons. Who have often quarreled, fought, gorged from valley to valley, from castle to castle, from village to village, from country to country. Less to take, if not rapine, less to enlarge than to establish a place, a domain, a territory as part of oneself, from which the other will be excluded, tolerated at best, always in an extraneous situation. And suddenly, these Lilliputians are leaving. Do you realize, my friends, what such a departure represents? It is not exactly a question of travel, of the traveler’s curiosity – there has always been Herodotus, Marco Polo. No more the trade or the wandering that follows the path of exchange. Demographics, economics, politics of the powers, religion can nourish the motivations and satisfy the historian. Still, there needs to be a higher determination that guides choices. How to name it? The call of the unknown, the will to force the destiny, the ability to face the mystery? We are lacking beings, says the philosopher. Beings of desire. To miss is to have the desire of something else, which can not be defined since one has a negative idea of it. An incredible audacity: to deny the present to open oneself to the mystery. Standing, eyes open on the horizon. To confront the immensity of the ocean and its fury, to approach lands as vast as the sea, to sink deep in immense forests, shadow cathedrals swarming with a strange life, to follow the trace of the sun in the mirages of gold of the desert, to discover bizarre, incomprehensible, wild manners, and peoples more numerous than grains of sand on the beach. But above all to be in front of the excess in the excess without yielding. And to stay, or to come back, with in the head, the distant little world, so far away, left so long ago, whose tiny outlines slowly become numb in the sleep of remembrance. What was at the heart of this obstinate will? Perhaps the secret trace of a very long memory. After all, each of us goes down more or less from distant invaders. Celts, Franks, Germans, Goths, who were our ancestors? And have we kept in the recesses of our desires the imprint of these ancient migrations?

Asia, Africa, America, all these continents were not equally offered to the coming settlers. Asia, Africa, worlds too full already or natures too difficult, too hostile. There remained America, and particularly North America, with a cowardly occupation whose Atlantic coast, at the 40th parallel, was not altogether so exotic for Europeans. The spirit of enterprise of Protestants did the rest. One could build a New England and imagine that one would reproduce while purging it in a sort of Virgilian dream the old mother Europe. What is America then? Viewed retrospectively, it can appear as the development of a simple historical conjuncture, as the fruit of chance and necessity. Or would one say such was the fate inscribed, almost from all eternity, on this piece of continent? Why do I think that, thinking of America, I have the feeling of an infinitely old reality and an unfinished promise? In this sense, if America stems from a destiny, this destiny is always to come, always remains an opening on the unexpected.

This for example, which is about understanding. We Frenchmen have the religion of a well-conducted text, according to the order of the reasons: we like a well-conducted reflection and what is more amiable than to go from the idea to its consequences; we are legislators of writing. American pragmatism tends to advance general ideas that are supported by the analysis of facts. [I put this in bold, it was not in the letter.] This does not free them from prejudices, but gives them a powerful mobility and protects them against the excess of systems. But I believe that in the intellectual crisis that we are going through, we will not be able to find the way if we do not find a satisfactory understanding of the multiple and multiplicity, which is blocked, or at least thwarted, by the need for a unitary interpretation, a deeply rooted need as it comes from Christian theology and its Hebrew antecedents. Because America is essentially multiple, because the unitary is at home only the means to associate and coordinate these multiplicities in the faith in America and the faith in the individual, perhaps the novel thoughts will come from across the Atlantic. And as usual, we will systematize them. For the pleasure of order. Eternal youth of America? But what is America?

Forgive me for writing to you so late. (I hope this overloaded letter will come to you.) Thank you for giving me some news. So few people do it. But I am a bad letter-writer. I run after the money that runs after clever evils and I miss the time.

I kiss you,

Georges, October 2, 1993.