I have already written in a recent post all the happiness that the discovery of Jón Kalman Stefánsson and in particular his Romanesque Trilogy had brought me.

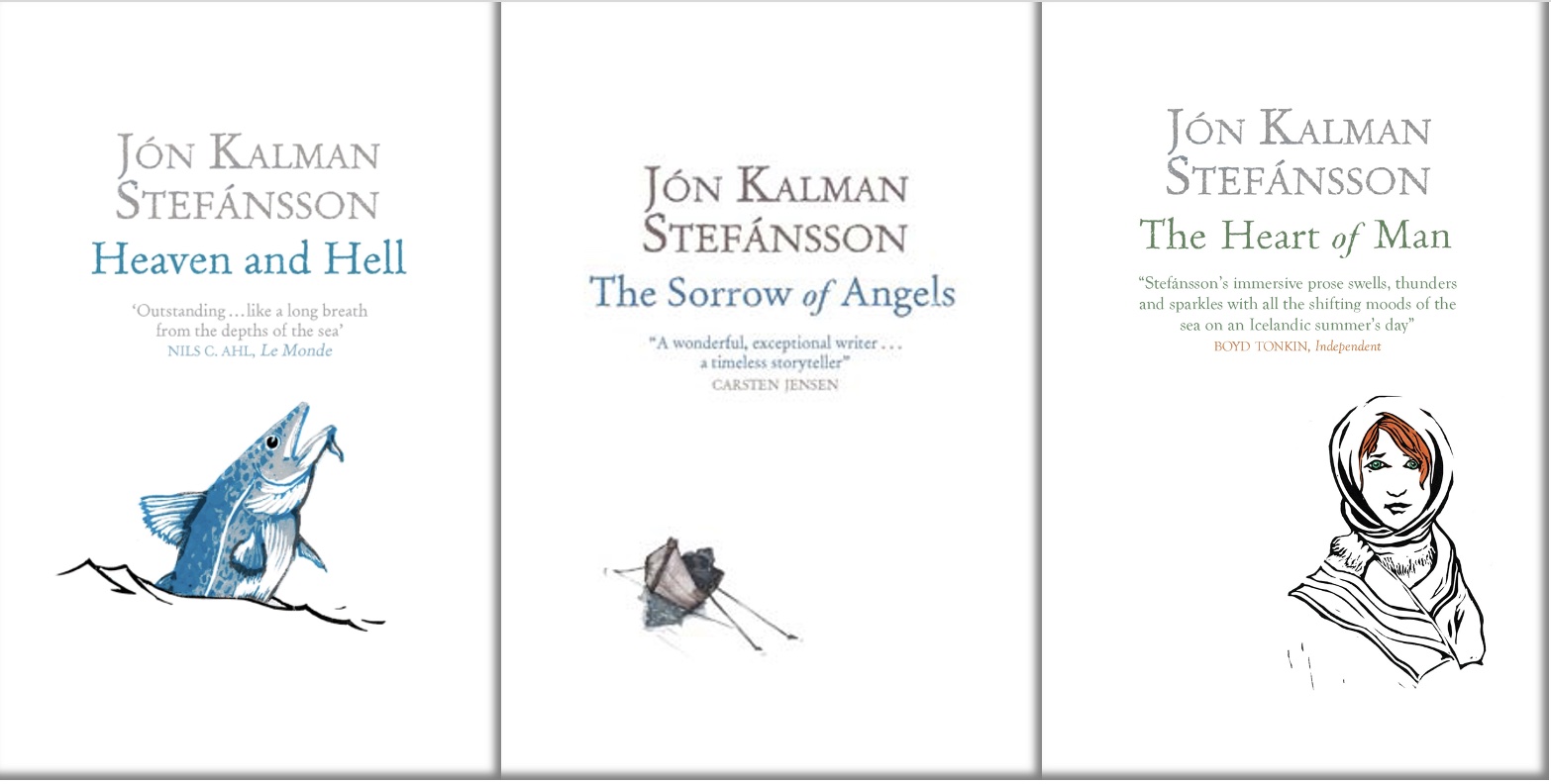

- Himnaríki og helvíti (2007) / Heaven and Hell (MacLehose Press, 2010)

- Harmur englanna (2009) / The Sorrow of Angels (MacLehose Press, 2013)

- Hjarta mannsins (2011) / The Heart of Man (MacLehose Press, 2015)

I am lucky to have enjoyed the same happiness with the equally magnificent Family Chronicle:

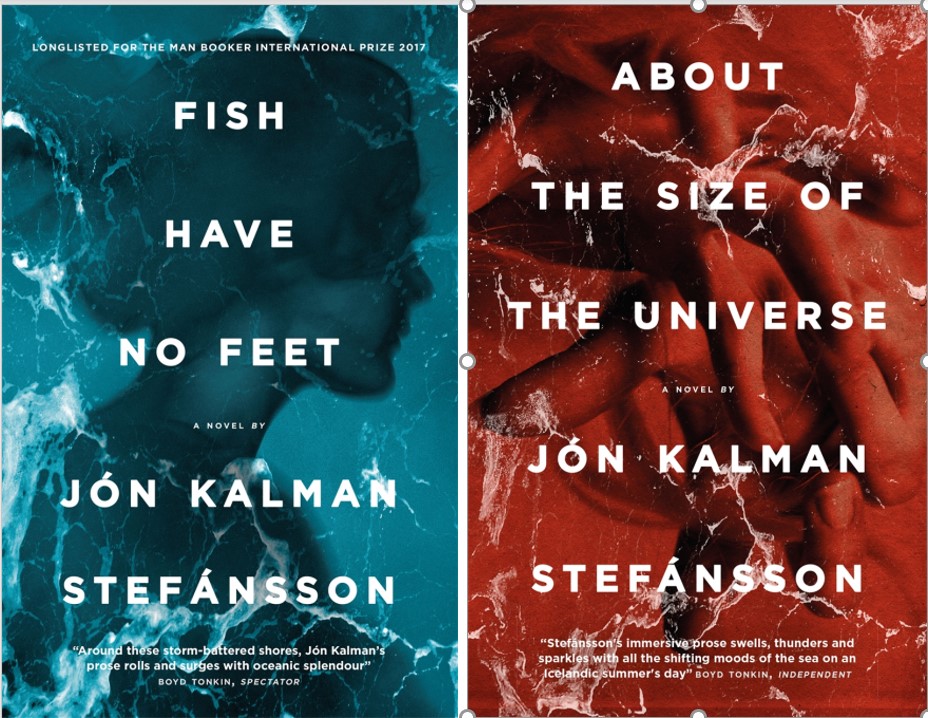

- Fiskarnir hafa enga fætur (2013) / Fish Have No Feet (MacLehose Press, 25 August 2016)

- Eitthvað á stærð við alheiminn: ættarsaga (2015) / About the Size of the Universe (MacLehose Press, 2019, translator Philip Roughton)

It’s difficult for me to talk about literature. A friend recently asked me what “explaining” meant, and after some exchanges, we arrived at “giving to see”, “making luminous”, “giving a particular perspective”, and obviously there can be an infinity of perspectives. We were talking about science and mathematics. Literature, novels, poetry explain often and much better than the human or even exact sciences… Stefánsson does.

So here are two short extracts:

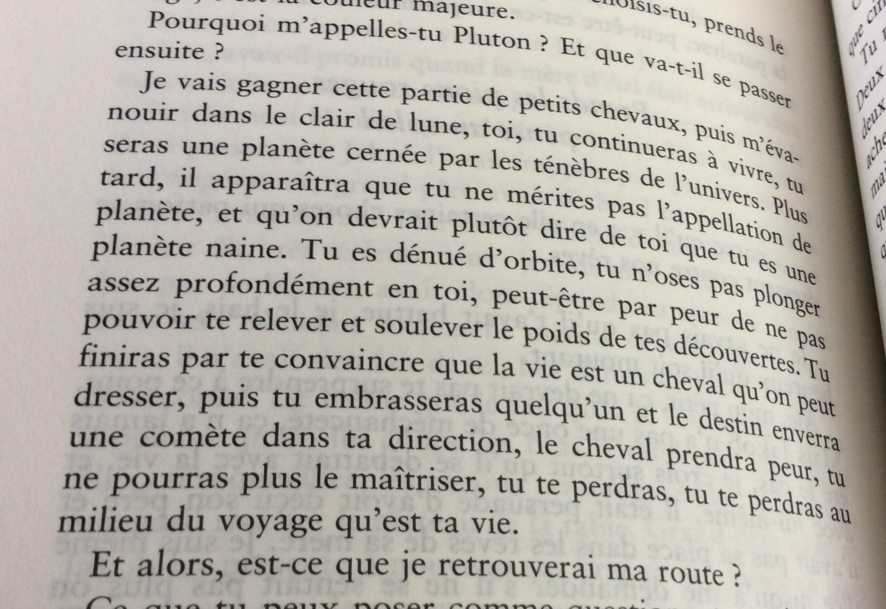

Why do you call me Pluto? And what will happen next?

I will win this game of small horses, then disappear into the moonlight, you will continue to live, you will be a planet surrounded by the darkness of the universe. Later, it will appear that it does not deserve the name of planet; and that we should rather say of you that you are a dwarf planet. You are devoid of orbit, you do not dare to dive deep enough within yourself, perhaps for fear of not being able to get up and lift the weight of your discoveries. You will eventually convince yourself that life is a horse that can be trained, then you will kiss someone and destiny will send a comet in your direction, the horse will get scared, you will no longer be able to control it, you will get lost in the middle of the journey that is your life.

And then, will I find my way back?

This reminds me of a beautiful and terrible quote by Wilhelm Reich in Listen Little Man. Then there is this feminine side of the author. Not only in his themes, but also in his way of writing. There is no better argument, no better response to this hatred against the woke movement or of the loss of the masculinist power. It is by loving what is not like us that we love better and that we can lose or abandon our part of darkness, by developing or seeing better what is luminous.

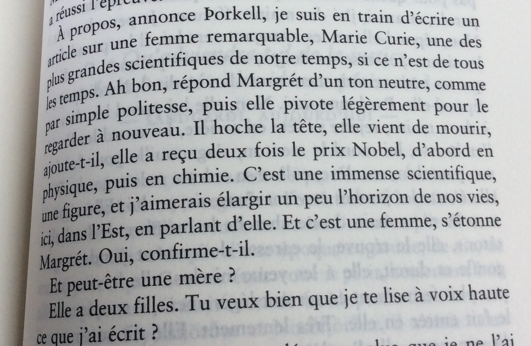

By the way, Þorkell announces, I am writing an article about a remarkable woman, Marie Curie, one of the greatest scientists of our time, if not all time. Oh good, Margrét replies in a neutral tone, as if out of simple politeness, then she turns slightly to look at him again. He nods, she has just died, he adds, she received the Nobel Prize twice, first in physics, then in chemistry. She is an immense scientist, a figure, and I would like to broaden the horizon of our lives a little; here in the East, talking about her. Is it a woman, Margrét is surprised. Yes, he confirms.

And maybe a mother?

She has two daughters.

And as I finished my other post with Cynthia Fleury, I will end this one with another discovery, that of the filmmaker Terence Davies, author among others Of Time and the City, Benediction and the very beautiful short film Passing Time.