I advertise this book to my friends and colleagues. This is definitely the book I wish I had written. Everything is said, as we sometimes say! You will find previous articles here and there.

The workers of Silicon Valley

Chapter 6 is dedicated to developers, coders. Historian Alfred Chandler has shed light on how the centralization of information and decision-making by top and head managers, located at the top of separate divisions, constituted a comparative advantage for the leading companies that emerged in the 19th century in the fields of transport, energy and communications. Managers prevail as intermediaries between producers-suppliers and customers-demanders. They embody and concentrate power for functional reasons, because they allow the coherent, hierarchical and vertical circulation of information and decision-making within companies.

Through the writings and conclusions of F. Brooks ([in The Mythical Man-Month] shows an inverse pattern. According to him, to give free rein to the iteration process necessary for software production, the work must be coordinated horizontally, to favor support for the continuity of software development. He pleads in favor of small teams gathered around a central worker, whom he compares to a “chief surgeon” placed, no longer upstream and overhanging as in the large companies analyzed by A. Chandler, but at the heart of the action.

This mode of organization aims to adapt to the type of product that is the software and its characteristics in terms of production. Developers project themselves into a job without knowing the outcome, the time required, or the final properties of the production process. Software design thus necessarily proceeds via projections. If the developers can rely on scenarios, visions, schemes, diagrams, these do not allow a lasting and stable coordination unlike scripts in the cinema or scores in the field of music. This dimension explains the role assigned to managers in Silicon Valley companies. It is not a question of circulating information between managers at the top of different divisions to control the work of subordinates but of ensuring the coherence and coordination of the team within the framework of a project. […] If the developers cannot rely on downstream continuity supports, they mobilize a series of tools upstream of the production process [Pages 316-18].

Start a business

Founding a business is a more radical choice. […] This entrepreneurial move to action turns out to be paradoxical if we consider the treatment that developers are given within Silicon Valley companies and the low chances of leading a company to success, i.e., according to the criteria of investors, a sale or an IPO. For those who work for the big names in tech, leaving to start your own company means giving up, for an unknown period of tim,e a high salary, bonuses, health insurance, free catering and transport services, maternity and paternity leave, child care systems, etc., all for a greater amount of work. From this point of view, the creation of a business does not meet the criteria of rational choice within a professional group that is nevertheless attached to objectivity, reason and logic.

While many cite Silicon Valley’s entrepreneurial culture to justify this shift, they also point to the desire to retain control of the value possibly generated by their work. Indeed, the creation of a business proves for the developers not the surest means of enrichment but the one which represents the greatest potential [Page 335].

Burning man, an inverted carnival

When I started reading the last part of his book, I wondered why Olivier Alexandre devoted so many pages to this very special event that is the Burning Man festival. The chapter devoted to it therefore deserves careful reading, starting with a note on page 529: “The habitus is a set of enduring dispositions which consists of categories of appreciation and judgment and engenders social practices adjusted to social positions. Acquired during the early education and the first social experiences, it also reflects the trajectory and later experiences: the habitus results from a progressive integration of social habits. This explains why, placed in similar conditions, the agents have the same vision of the world, the same idea of what can be done and what cannnot be done, the same criteria for choosing their hobbies and their friends, the same clothing or aesthetic tastes” [Anne-Catherine Wagner in Les 100 mots de la sociologie].

It is from this remarkable point of view that the term “connection” finds multiple uses in Burning Man: connecting with others, reconnecting with oneself, connecting with the festival, connecting the different stages of one’s life (or according to Steve Jobs’ formula “connect the dots”) or take MDMA or LSD to better “feel the connection” (with other people, the environment, etc.), etc. This mode of engagement, which is based on immediacy and interaction, ultimately leads to bringing into play habits, stabilized and incorporated representations, including in terms of self-representation. This bringing into play of habitus proceeds from a series of tests [Pages 361-62].

As seen above, Silicon Valley is characterized by a significant turnover of workers. Their high geographic mobility poses uncertainty about the sustainability of relations. The idea that a departure almost overnight is within the realm of possibility remains deeply rooted in people’s minds. Especially since Silicon Valley has had one of the highest divorce rates in the country since the 1980s and expatriates rarely see their families. For these various reasons, the Burning Man represents for certain participants a “family” of substitution. In 2008, 67% of participants were in contact with Burners outside the festival [Page 380].

For the participants, the festival tends in different ways to enchant a world that they contribute the rest of the year to disenchant through the production of digital tools, measuring instruments, calculation methods and a rationalist approach. Art is not considered an object but a support for interaction. As a component of an environment, it allows the development of skills before, during and after the festival. The latter confronts the Burners with a series of tests whose learning and experiences are reinvested during the rest of the year, within the framework of projects. In this, the Burning Man is not a simple party, a festival or a laboratory, but a device that makes possible the interconnection between individuals, repertoires of skills and communities of practice. It leads to the construction of an ethos oriented towards change. [Page 382]

Silicon Valley, a political project?

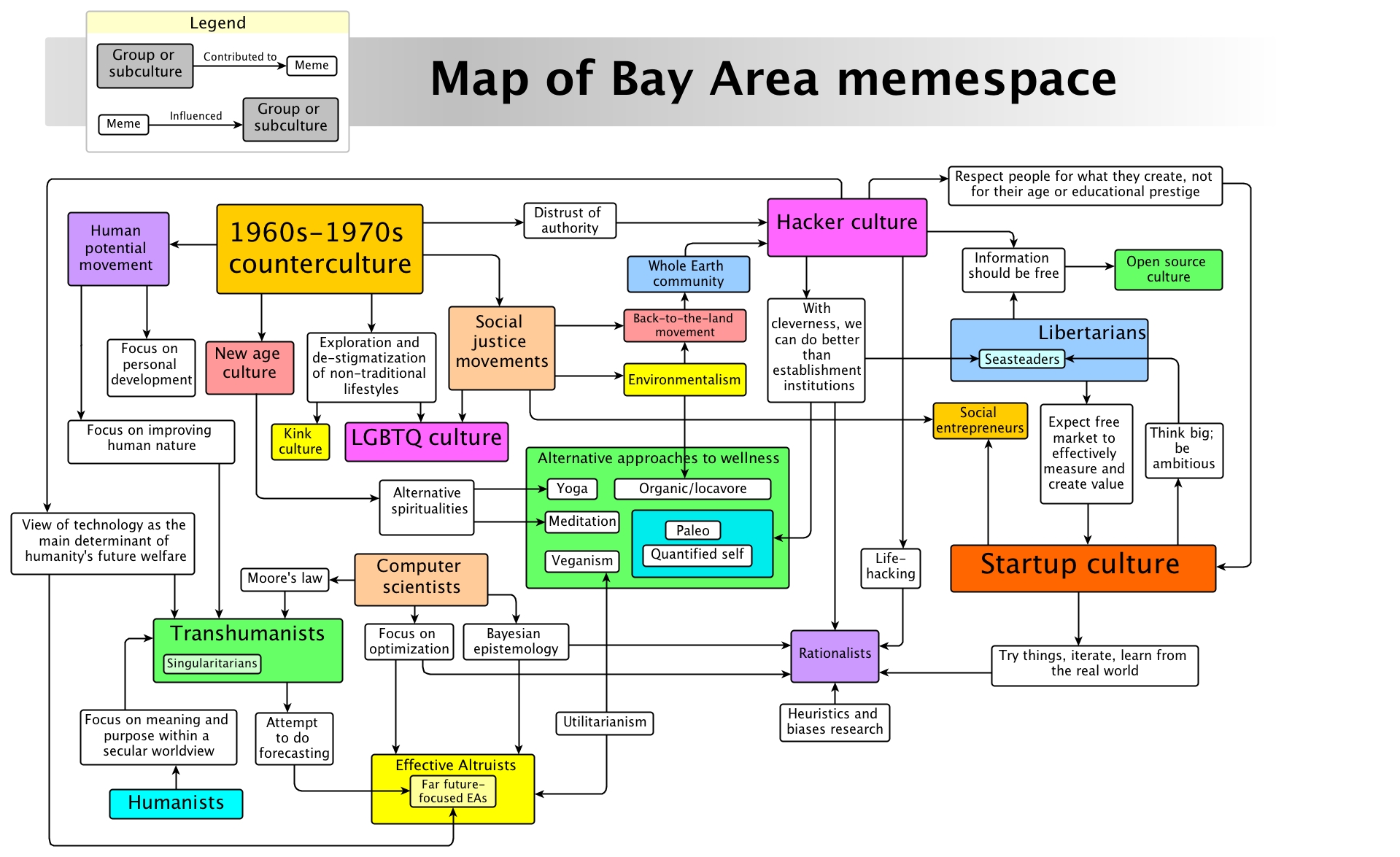

Olivier Alexandre ends his book with what the region represents from a political point of view. A place of experimentation par excellence, this region is also at the origin or development of movements such as libertarianism, transhumanism and long-termism, whose influences and relationships are shown in the following figure (see page 361 and original source dated 2013 on Julia Galef’s blog). They are themselves mixtures or synthesis of anarchism, liberalism and isolationism [Page 387]. Their political vision would be characterized by a lack of empathy as well as a willingness to go beyond the boundaries of mind and body [Page 388].

Once again, Olivier Alexandre gives a subtle description of the region: one can legitimately wonder about the novelty, the coherence of this constellation within a region which has a majority of pragmatist progressives, pro-government libertarians, liberals voting mostly Democrats, who (like Elon Musk) favor the investor state while demanding tax cuts [Page 394]. And adding in note 12, page 501: Libertarians are only a minority in Northern California. The Libertarian Party had 2,600 registered voters out of 468,000 voters in the city of San Francisco in the early 2010s.

I can’t resist adding here some additional references for my own archives:

– The vast majority of tech entrepreneurs are Democrats — but a different kind of Democrat. A big new survey tells us a lot about Silicon Valley’s politics by Dylan Matthews, Sep 6, 2017

– Techno-feudalism by Cédric Durand. See a review by Jérémy Lucas on Dygest (in French).

– Mouvement syndical et critique écologique des industries numériques dans la Silicon Valley (Labor movement and ecological criticism of the digital industries in Silicon Valley) by Christophe Lécuyer dans Réseaux 2022/1 (N° 231), pages 41 à 70

– Some articles with the #politics tag on this blog, including the recent work of Anthony Galluzzo who participated with Olivier Alexandre in programs on France Culture.

The impact on the region is known and is not new even if it has increased. The attractiveness of the region has left too many people behind and the observation already existed in … 1979. See for example Silicon Valley, more of the same that I published in the early days of this blog. The following extract deserves to be copied here again: “In 1979, I was a graduate student at Berkeley and I was one of the first scholars to study Silicon Valley. I culminated my master’s program by writing a thesis in which I confidently predicted that Silicon Valley would stop growing. I argued that housing and labor were too expensive and the roads were too congested, and while corporate headquarters and research might remain, I was convinced that the region had reached its physical limits and that innovation and job growth would occur elsewhere during the 1980s. As it turns out I was wrong” by AnnaLee Saxenian.

“I don’t necessarily blame the workers. […] By and large the real people in the tech industry don’t seek to do harm. In fact, they seek to do good, at least in the way they see it, especially the elders, the OPs [the Old Programmers]. But they are just one small piece in a larger system that is sinister. One of the things that I try to explain to people I work with about this industry is that one of the best parts of it is working with very smart people on projects you devote yourselves totally. When you work like that, there is something that happens… that makes you forget everything else. It’s like in a war… it causes people to develop a psychology where they become myopic to what surrounds them. That’s passionate work, and it’s wonderful. But if you go nearsighted, you can’t see anything outside your field of vision because you’re immersed in it. As a result, they are not against the right to housing, or more social justice. It’s just that it’s not part of their consciousness, they don’t feel like they have the ability to care or think about it, because they’re so focused on the task in front of them. When we started this organization, I had the good fortune to have a few experiences that opened my eyes to the corrupting influence of money. So we don’t do high-priced galas, I don’t go to wealthy family foundations, corporations or anything else to raise funds [Page 438, Brian Basinger, July 2016].

It is difficult to finish reading such a book and to review it. I can only encourage one last time to read it. I will limit myself to a few additional quotes: “The painful paradox of modern technology is that it has been so successful, but it has also failed miserably. We live in this paradox that challenges the very meaning of being modern” [Page 455, by Lee Bailey in The Enchantments of Technology].

This book is a description of an ultra-competitive but enchanted world, Balzacian in that the grandeur of ambitions meets the fragility of solutions. The analysis will serve those wishing to “change the world” as well as their critics determined to think of new models [Page 456].

Many thanks to Olivier Alexandre.