Degroof has produced one of the best books describing entrepreneurial ecosystems as I have already mentioned in 2 previous posts including Part 2 : Ecosystems & Culture.

In the last part of his book, he switches to the impact of MIT and its ecosystem.

This is a well-known topic as you could read in Entrepreneurial Impact: The Role of MIT. Degroof reminds us (pages 183-89) of the biotech startups around Kendall Square (Biogen, Genzyme) as well as the R&D of big pharma relocating around, such as Swiss Novartis. It’s not only about biotech as Lotus Development or Akamai exemplify. He also mentions some alumni who became famous entrepreneurs or investors, Hewlett (36), Perkins (53) or Swanson (69). He does not mention Noyce (53) though, and his tinkerings (more here and there) or Haren (80) for French people. There could be hundreds of others!

He also adds about the impact of local accelerators from CIC in the late 90s to MassChallenge and TechStars. I am a little less convinced about the international impact MIT had in a more topdown institutional way. What is the exact outcome of partnerships in Singapore, Hong Kong, Abu Dhabi, Spain or Portugal. The Deshpande Center certainly inspired many initiatives including the Innogrants I managed at EPFL in the mid 2000s or even what I do today.

Degroof also develops the importance of teaching and training: “In trying to reconcile the tension between rigor and relevance, Aulet argues convincingly that entrepreneurship should be framed as a craft as opposed to a science or an art. Like a craft, it is built on fundamental concepts. A potter, for instance, needs to master the basic mechanical and chemical principles of his craft. Knowing those does not guarantee success, but they considerably improve the chances. Like a craft, entrepreneurship is best learned through apprenticeship, or learning by doing, rather than relying only on lectures or manuals.” [Page 212]

Again I am a little less convinced about this generally-mentioned point: “There is a strong belief at MIT that entrepreneurship is a team sport. It is based on the evidence that teams of founders tend to perform better than individual founders, and that complementary teams tend to do better than homogeneous teams. Following on the heels of the I-Teams class, nowadays, most teams in entrepreneurship-related courses or contests are required to be composed of a mix of engineering or science students with management students. This has become an important feature and a great strength of entrepreneurship training at MIT. Both groups benefit from each other’s contributions. Engineering and science students discover the market dimensions of the projects with the help of their peers from the business school and learn that it is not enough to build a better mousetrap, while the latter benefit from scientific and engineering insights. Both groups are forced to deal with cultural differences and with more complex team dynamics than what occurs in homogeneous teams. The results are stronger teams and more effective projects.” [Page 214]

Entrepreneurship is a complex venture and entrepreneurial ecosystems are complex and fragile settings. Degroof convincingly describes why Boston has become a model. He does not really develop why it has not been as succesful as Silicon Valley, with a similar culture though. Paul Graham’s Ycombinator had moved from Boston to Silicon Valley as mentioned in Why Boston Should Worry. When I visited Novartis people in Boston, some claimed that Silicon Valley was to Boston what Boston was to Europe. Yes, Boston was more innovative than Europe and that is why Novartis moved some R&D to the West, but when Novartis bought Chiron in Silicon Valley, Novartis discovered going further West was again more adventurous. (See Myths and Realities of Innovation in Switzerland).

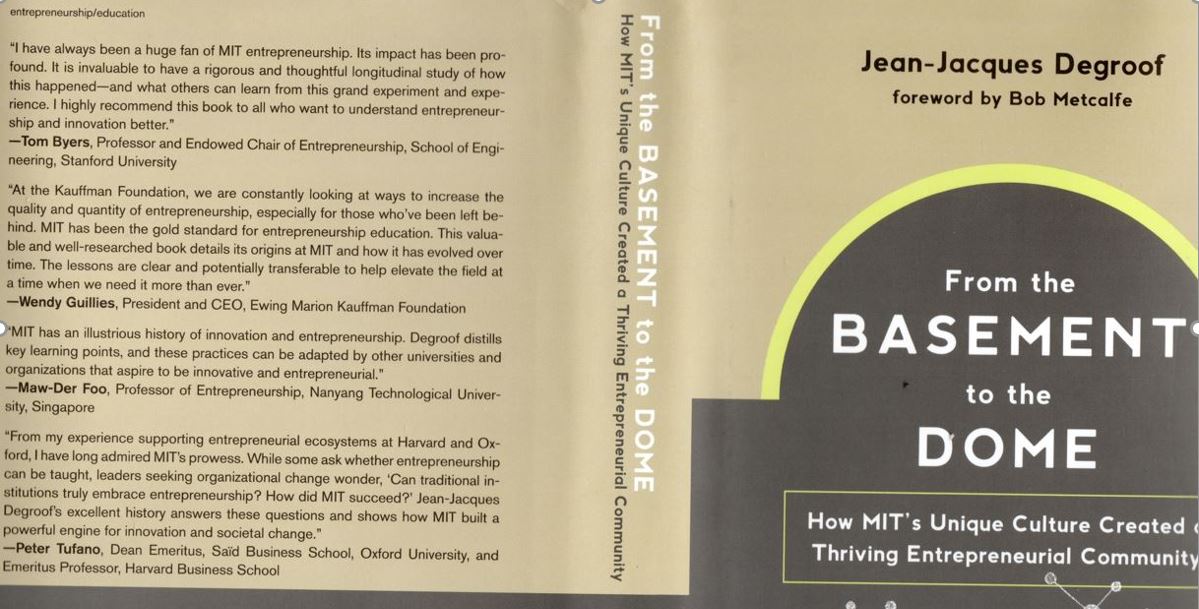

But these debates are secondary to the lessons learnt and synthesized by Degroof. A lot of inspiration is to be found. And coming back to the great foreword by Metcalfe : recreating MIT’s renowned entrepreneurial ecosystem is not a simple task. There is no copying MIT’s ecosystem and pasting it into another institution. The founding principles and unique cultural elements that came together to create the “secret sauce,” as Jean-Jacques calls it, the ground-up nature of what has grown and thrived at MIT, are not easy to duplicate. That does not mean that there are no concrete lessons to be learned, that there is not knowledge that can be translated and adapted for other universities and economies. Today, as a successful and seasoned entrepreneur, I still frequently look to MIT in my efforts to build a thriving entrepreneurial ecosystem at the University of Texas. I don’t hesitate to reach out to my extensive network at MIT for answers to questions of theory and practice. From there, I have been able to make great strides in my goal. I may not be recreating MIT, but I am modeling what I do after the very best and adapting it to the specifics I have here in Austin.”