This new episode of Philippe Mustar’s book relates to the history of Criteo, a startup already mentioned on this blog here and there.

For once, I disagree slightly with a quote from the book (which is not from the author): “The profile of the team formed by the three creators of Criteo is a perfect example of the one described theoretically by Kathleen M. Eisenhardt (Professor of Management at Stanford University and Co-Director of the Stanford Technology Ventures Program) as “the best it can be.” Kathleen Eisenhardt, based on a lot of research on the subject, defines (somewhat mechanically she herself admits) what a great team is:

– it initially consists of three, four or five people. If there are only two, it is not enough because there are so many things to do in a start-up and above all, being two does not offer a wide enough diversity of opinions, of points of view. If there are six, seven or eight, it is no longer a team, it is a group whose management and coordination take too much time.

– it is multidisciplinary and transversal, that is to say it combines skills in engineering, marketing, finance. But, these skills must be real, that is to say not based only on a diploma, but on actual experience.

– it includes people who have already worked together, this is an important asset because the creation of a start-up is made up of stressful situations, which are easier to share with people you know.

– finally, and this is more surprising, the “best teams” are those which have people of various ages, not only young people in their twenties but also others who have more experience. This often allows you to see different aspects of the same problem.

For Kathleen Eisenhardt, teams that meet these criteria are the ones that perform best. ” [Page 199]

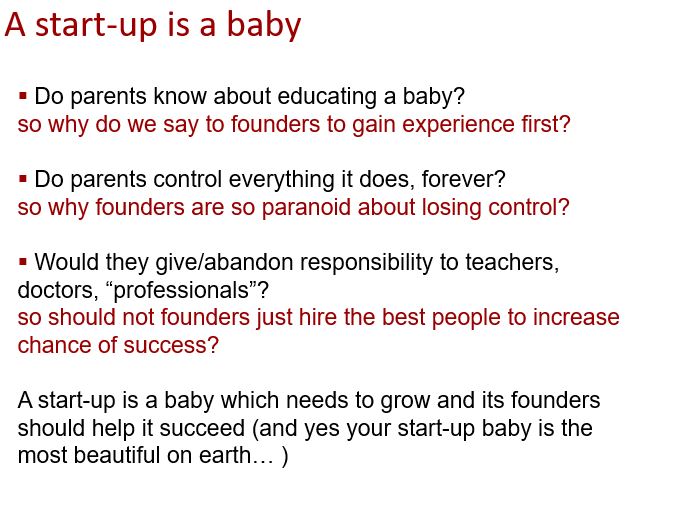

As much as I can agree if we talk about the management team, I believe that at the time of creation, the founders have different pedigrees. As I wrote in my own book in 2008, “A start-up is a baby created by its parents – the founders. They are responsible for its development and to help it adapt to an evolving world. It does not mean that a founder has to give up control of his start-up. Would a parent give up his child just because he has no experience in feeding and educating? Is the analogy of little value? There is also a responsibility in succeeding in the development. Experts will be used, medical doctors, teachers for the child, professionals, and consultants for the start-up. The Google founders kept such “ownership” during the company’s growth. Eric Schmidt has become CEO but he is more a partner of the two founders. Start-ups seldom develop that well and investors sometimes have to make tough decisions when they take away the “parent” power from the founders. Investors do not like to do this in general and only do it when they consider it absolutely necessary. This is an ideal world but everyone knows reality is more complex”. And I could add, two parents is probably the ideal model.

On the other hand, I fully agree with the sources of innovation: The sociology of innovation has shown that the sources of innovation, like those of the Nile, are multiple and sometimes difficult to identify. It also pointed out that ideas for new products or services are the most common things in the world, and even that they are always bad, always poorly framed and approximate at the origin. As Bruno Latour says: “All important discoveries are born ineffective: they are hopeful monsters,“ promising monsters ”. [Page 251] and the French text by Latour http://www.bruno-latour.fr/sites/default/files/P-92-PROTEE.pdf . [A short parenthesis about Hopeful Monsters, a term I knew only from one of my favorite novels, and I blogged about it here.]