If you missed Part I, it’s here. All the culture of Silicon Valley was born in these early years. Here are a few examples.

In the early days of the semiconductor, it was mainly about high-quality research: With an absentee boss, Sherman Fairchild, on the East Coast, the group could focus mainly on doing pure research, with no boss to bug them. Their main direction came from intense competition between each other. No VC or corporation would finance anything like this now! [Page 14] The authors are right. Only Google maybe is doing it with or without VC or boss approval and peer pressure is similar.

They finally make and ship their first product in 1958, 100 transistors to IBM. [Page 17]

Jack Kilby was awarded the Nobel prize in physics in 2000 for the invention of the integrated circuit. Unfortunately Bob Noyce had died 10 years earlier and Jean Hoerni passed away 3 years earlier. The Nobel prize is never awarded posthumously. The scientific community informally agreed that both Kilby and Noyce had invented the chip and that they both deserved credit. [Page 21]

Chapter 2 is about a non-startup, Hughes Research Labs, based in Los Angeles.

We did not have stock options; few of us even knew what they were. [Page 48]

Having dynamic leaders who gave free rein to ambitious young engineers and scientists meant that the engineers and researchers were stimulated by competition among themselves rather than by management layers above, which helped create an explosion of papers and patents. However, in both cases [at Fairchild and Hughes RL], the transfer of technologies from R&D to production was not easy. Although they were distinctly different organizations, both were very large corporate structures. But in the case of HRL, having R&D and production in the same physical location meant that discussions between the two groups were quite frequent.

Another difficulty was the lack of stock option program at HRL. This definitely caused significant personal turnover, especially among the non-attached young scientists who were hearing about the new utopic world, and its lucrative stock option packages, up in Silicon Valley. [Page 67]

Chapter 3: Intersil, a lost opportunity.

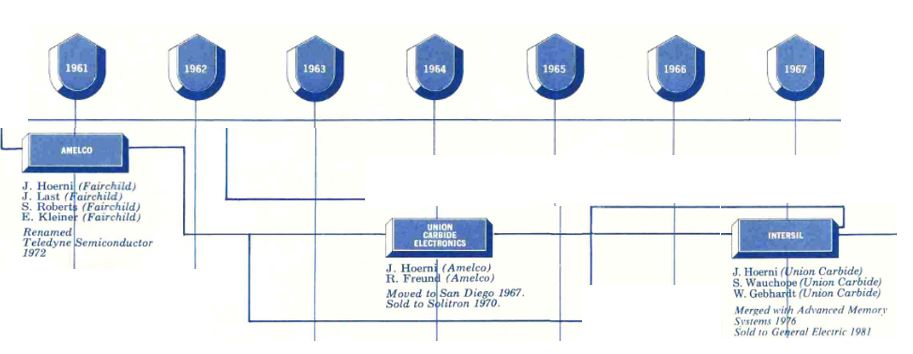

Another genealogy of Silicon Valley and extracted, the impact of Jean Hoerni.

Intersil was founded by Jean Hoerni, one of the eight traitors. The early days are best described as a mix of genius and chaos. The two most versatile personalities were Jean Hoerni and Don Rodgers, the VP Sales and also ex-Fairchild. Hoerni with 2 PhDs in physics was a shy genius quite the introvert but given to unpredictable mood swings. Rodgers was an extrovert. He came from the rough and tumble, hard-drinking, hard-living Fairchild sales team of the 1960s. One of the early frustrations was the ineffectiveness of the marketing department. [Page 71]

Hoerni’s contentious and rebellious personality often appealed to the young managers and engineers who were also looking for the next opportunity and also rejected conformism and authority, in part to the traumatism of the Vietnam war.

When I [Luc Bauer] started working with Hoerni, he strongly advised me not to be blindly loyal to any company, but only to my own ambition and goals. He said that if your employer doesn’t help you reach them, then you better change companies or start your own because life is too short. [Page 74]

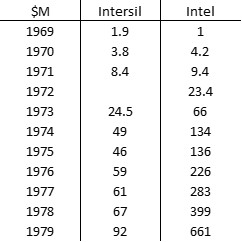

But Bauer talks about a missed opportunity and the reason follows: just have a look at the revenue growth of Intersil (founded in 67, IPO 72) and Intel (founded in 68, IPO 71):

Joe Rizzi, one of Intersil founders summarized his seven years at Intersil with two words: Lost opportunity. He said that all, or most of the seven product categories could have become sizeable businesses on their own, given enough care and focus to nurture their growth.

At the time, uncertainty in the market pushed to diversity of products. Intel’s narrow product focus was a risky gamble. [Page 102]. Intersil had $572M in sales in 2014 and was acquired by Renesas in 2017. Intel is now a $71.9B business…