In venture capital, returns on investments is the ultimate metric and although it is not very difficult to understand, there are many little tricks worth knowing about!

The reason of this short post is a recent article my friend Fuad advised me to read from the Financial Times : The parallel universe of private equity returns by Jonathan Ford. If you are not a subsciber to the FT (and I am not), you may not be able to read the article so here are short extracts: “Ever wondered about the extraordinary performance figures that listed private equity firms trumpet in their official stock market filings? […] Not only do the firms generate stratospheric numbers — far higher than anything produced by the boring old stock market — but they can apparently do it year in, year out, with no decay in returns. […] The reality is that these consistent IRRs show nothing of the kind. What they actually demonstrate is a big flaw in the way the IRR itself is calculated.”

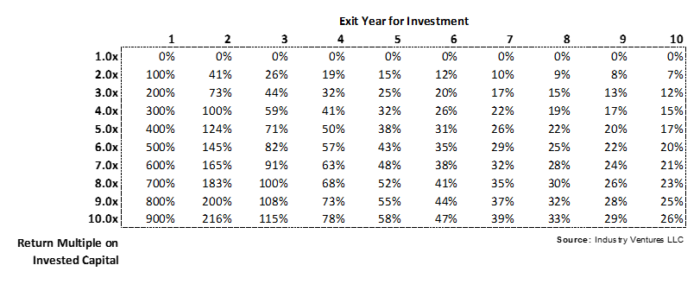

When I looked at venture capital (VC) returns in the past, I learned you must carefully look at what IRR means. It looks simple at first sight as the next table shows, just simple math:

So the first question you care about is what matters: IRRs or multiples? And my simple answer is “it depends”. Up to you!

Secondly, measuring returns makes a lot of sense when you have your money back. Of course! But IRR and multiples can also be measured while you are still invested and when your investment is not liquid, which is the case for private companies in which invests private equity (PE) – venture capital belongs to PE. You can have a look at a former post of mine, Is the Venture Capital model broken? and among other figures look at this:

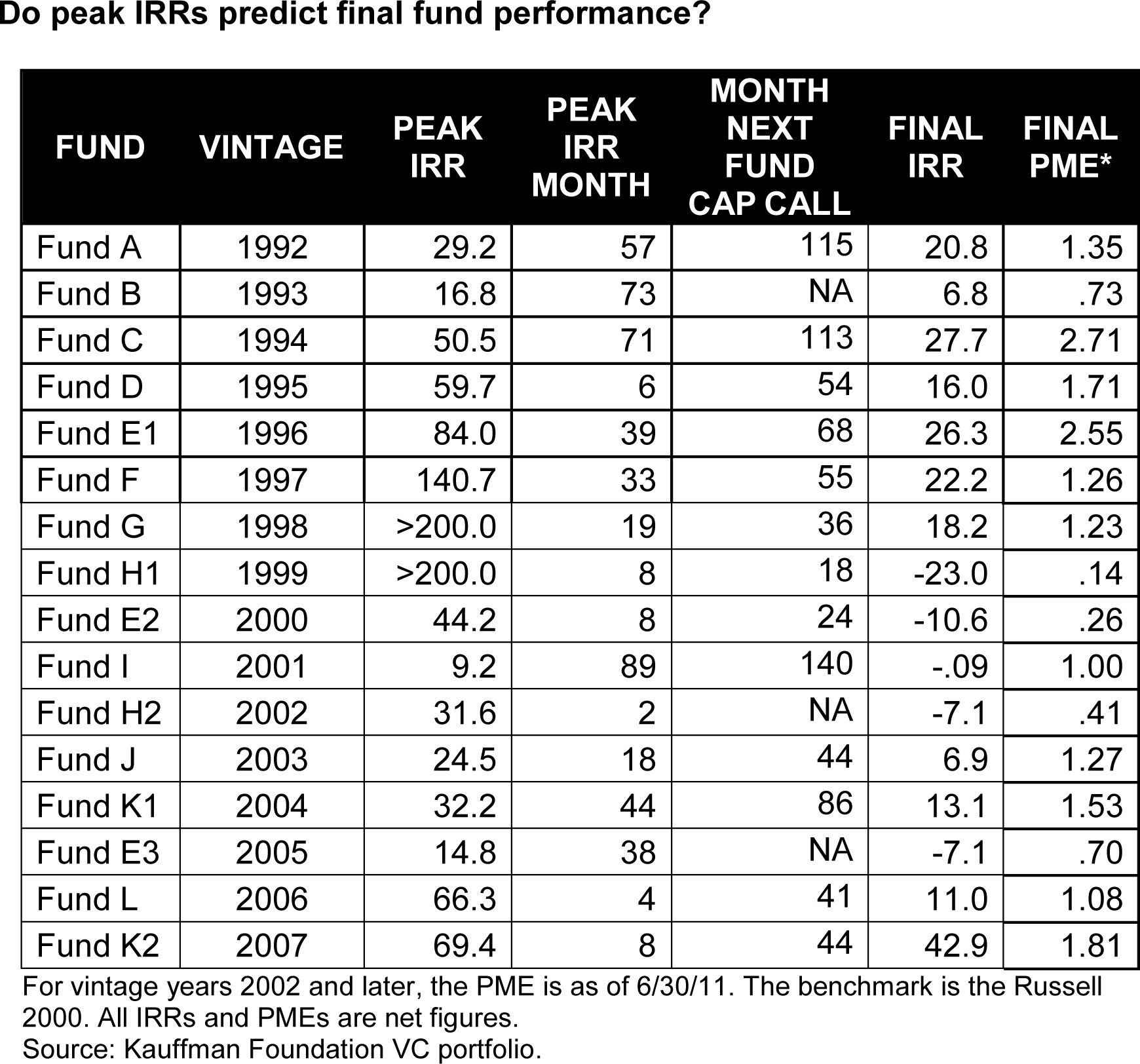

The VC performance according to the Kauffman foundation

The peak IRR is measured when your assets are not liquid whereas the final IRR is when you have your money back… A fund as usually a 10-year life (or 120 months) and you can check the peak IRR month.

Even more tricky, the money is called by periods to make the holding as short as possible: basically, when the money is needed to invest, though you commit to it for the full life of the fund. Measuring the real IRR begins to be complicated but what matters to me is the multiple from the day of commitment to the finaldah when the money is back… And to you?

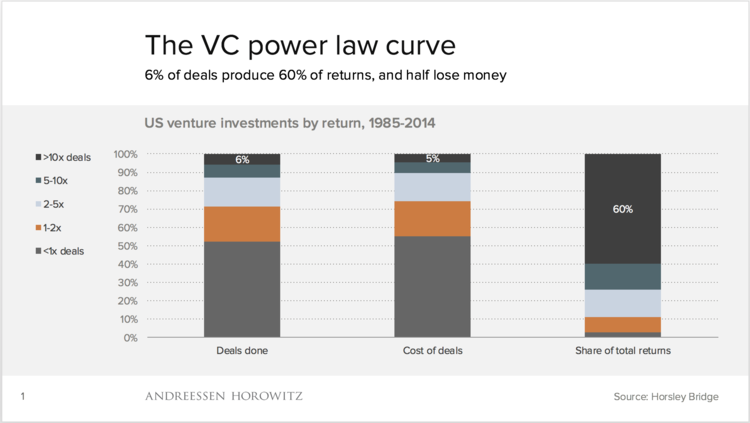

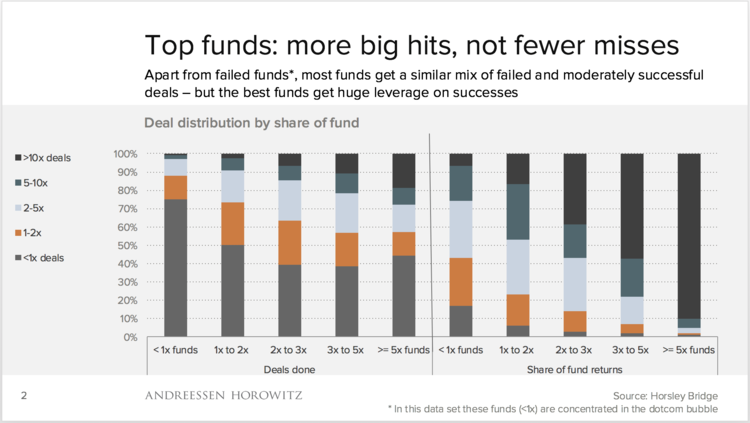

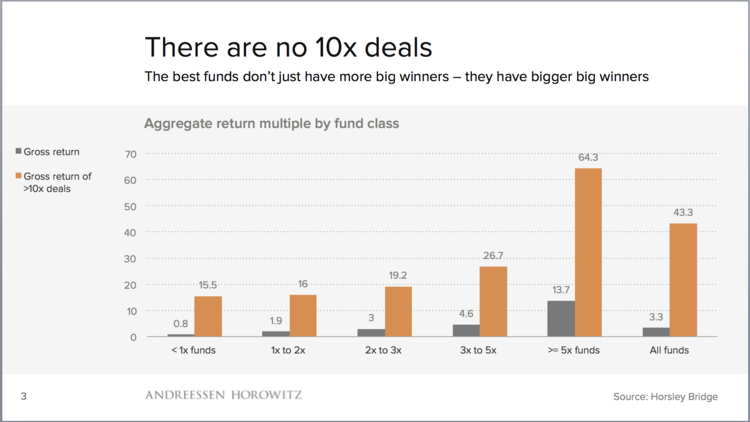

A final point I love to mention all the time is that VC is not so much about a portfolio of balanced investments. In the same post mentioned above, I added two links, and one of the best quote is “Venture capital is not even a home run business. It’s a grand slam business.”

Have a look at The Babe Ruth Effect in Venture Capital or In praise of failure. VC statistics are not gaussian, they follow a power law: