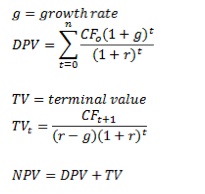

As promised, here are additional comments from my reading Peter Thiel’s class notes on start-ups at Stanford University (after the general ones in part 1 about innovation). And today, it’s about value creation. When I teach valuation techniques at EPFL, I provide similar information: value creation is future cash flows adjusted for time value (check Wikipedia for valuation using DCF). The difficulty with DCF is that in the case of start-ups most of the value appears in the very long term and given the uncertainty of start-up projection revenues, it makes DCF nearly useless… This is why, for start-ups, it is often easier to use techniques based on multiples & comparables (again check Wikipedia for valuation using multiples.)

Thiel enlighted me here by providing a very interesting explanation of why DCF still makes sense for start-ups. First he defines “Great Technology Companies”: “Great companies do three things. First, they create value. Second, they are lasting or permanent in a meaningful way. Finally, they capture at least some of the value they create.” Surprisingly (for me), the second thing is the most important: they are lasting or permanent in a meaningful way. He then introduces DCF with a growth rate:

and then he adds: “Tech and other high growth companies are different. At first, most of them lose money. When the growth rate—g, in our calculations above—is higher than the discount rate r, a lot of the value in tech businesses exists pretty far in the future. Indeed, a typical model could see 2/3 of the value being created in years 10 through 15. This is counterintuitive. Most people—even people working in startups today—think in Old Economy mode where you have to create value right off the bat. The focus, particularly in companies with exploding growth, is on next months, quarters, or, less frequently, years. That is too short a timeline. Old Economy mode works in the Old Economy. It does not work for thinking about tech and high growth businesses. Yet startup culture today pointedly ignores, and even resists, 10-15 year thinking.”

I will not add much more here but just mention that Thiel has in this Class 3 & 4 very interesting arguments about why competition may not be that good and monopoly not that bad for the economy and individuals… “Whether competition is good or bad is an interesting (and usually overlooked) question. Most people just assume it’s good. The standard economic narrative, with all its focus on perfect competition, identifies competition as the source of all progress. If competition is good, then the default view on its opposite—monopoly—is that it must be very bad. But exactly why monopoly is bad is hard to tease out. It’s usually just accepted as a given. But it’s probably worth questioning in greater detail.”

He does the analysis not only for companies but also for individuals with a moving section about fierce competition at Princeton, Yale or Harvard with an interesting comparison with Stanford: “Of all the top universities, Stanford is the farthest from perfect competition. Maybe that’s by chance or maybe it’s by design. The geography probably helps, since the east coast doesn’t have to pay much attention to us, and vice versa. But there’s a sense of structured heterogeneity too; there’s a strong engineering piece, the strong humanities piece, and even the best athletics piece in the country. To the extent there’s competition, it’s often a joke. Consider the Stanford-Berkeley rivalry. That’s pretty asymmetric too. In football, Stanford usually wins. But take something that really matters, like starting tech companies. If you ask the question, “Graduates from which of the two universities started the most valuable company?” for each of the last 40 years, Stanford probably wins by something like 40 to zero. It’s monopoly capitalism, far away from a world of perfect competition.”

He finishes with an analysis consistent with his first class on zero to one: “If globalization had to have a tagline, it might be that “the world is flat.” Technology, by contrast, starts from the idea that the world is Mount Everest. If the world is truly flat, it’s just crazed competition. (…) And yet, the single business idea that you hear most often is: the bigger the market, the better. That is utterly, totally wrong. The restaurant business is a huge market. It is also not a very good way to make money.

(…)

Where does venture capital fit in? VCs tend not to have a very large pool of business. Rather, they rely on very discreet networks of people. That is, they have access to a unique network of entrepreneurs. So VC is anti-commoditized. That kind of dynamic arguably characterizes all great tech companies, i.e. last mover monopolies. Last movers build non-commoditized businesses. They are relationship-driven. They create value. They last. And they make money.”

More to come…