Xavier Comtesse has just published an excellent report The Health of the Swiss innovation – Ideas for its strengthening, which he gave a summary on his blog, Innovation in Switzerland: it is primarily the domain of Health! This is a very interesting report and it is challenging for me because it “proves” that Silicon Valley is not and should not be a model for innovation in Switzerland: in his introduction he states that “the success of Switzerland in this area is still largely and for many people a mystery, especially since the only model actually known and studied is that of Silicon Valley and it does not fit, as we shall demonstrate, that of Switzerland. Although this model has made California the envy of all, it seems to have finally not been fully copied by anyone.”

But as Comtesse is a bit “Contrarian” (as I am also – my friends often accuse me of debating with myself), he cannot be satisfied with the health of the Swiss innovation. “As soon as the lines of the Swiss model will emerge, it will also show its weaknesses. This will allow us to propose changes to the current situation for a successful future evolution.”

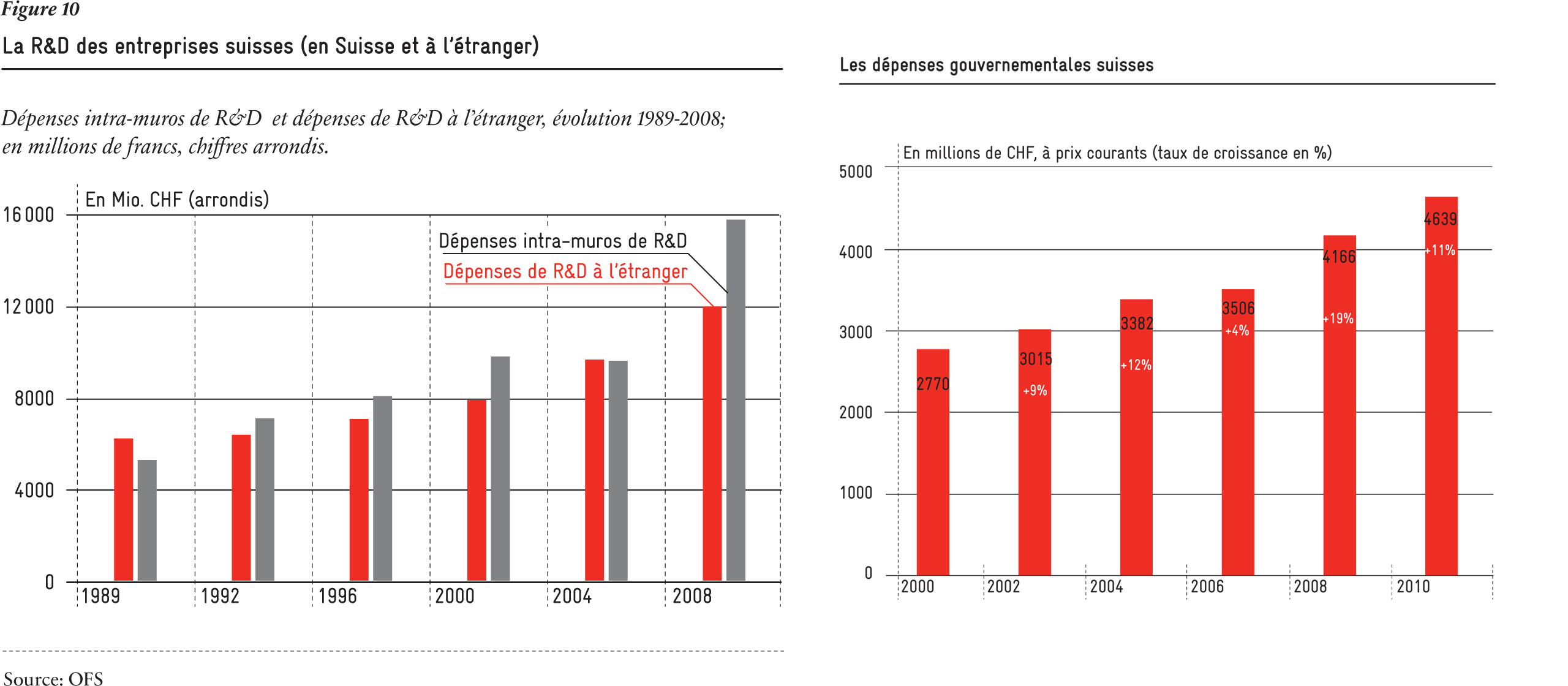

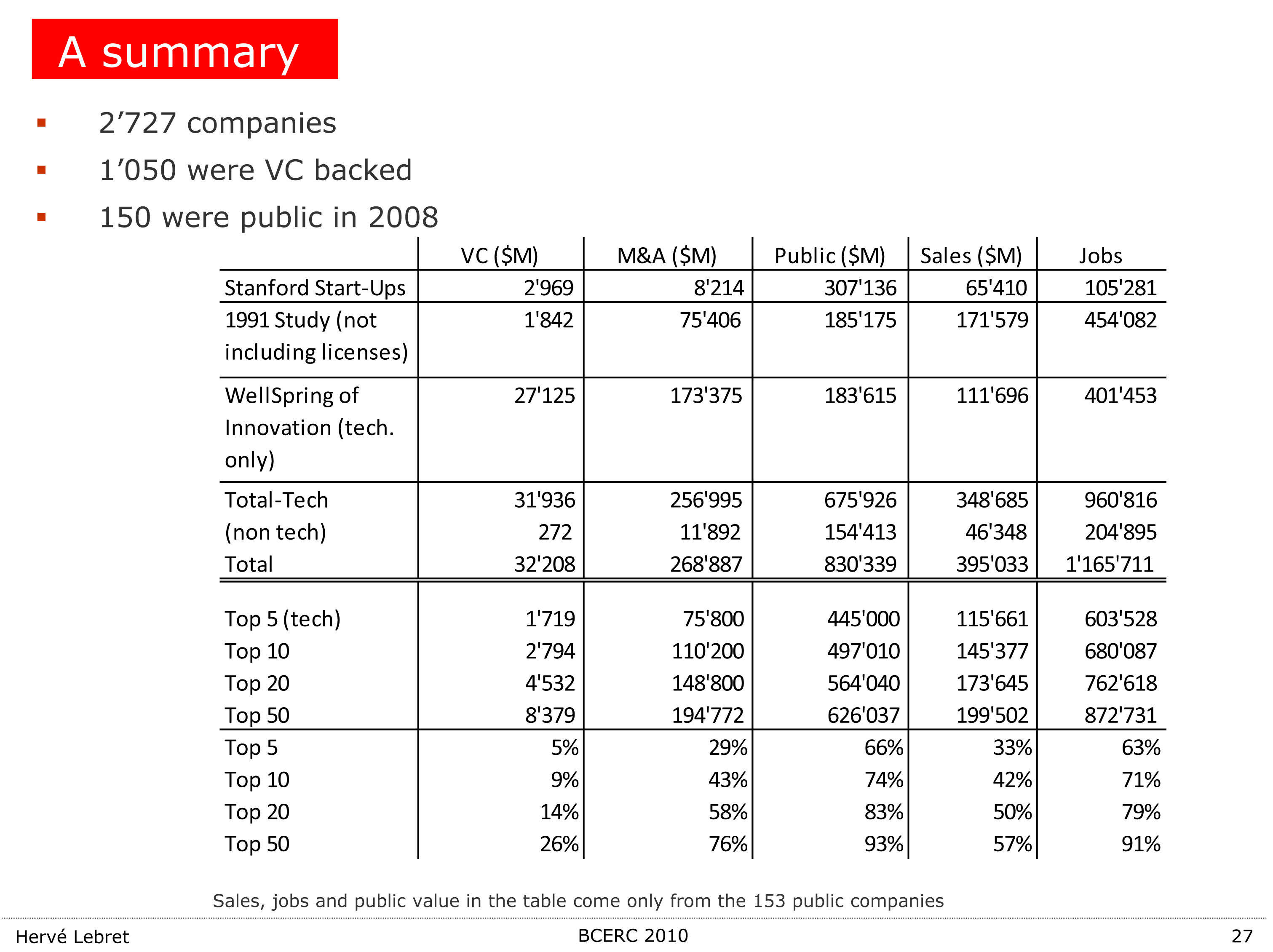

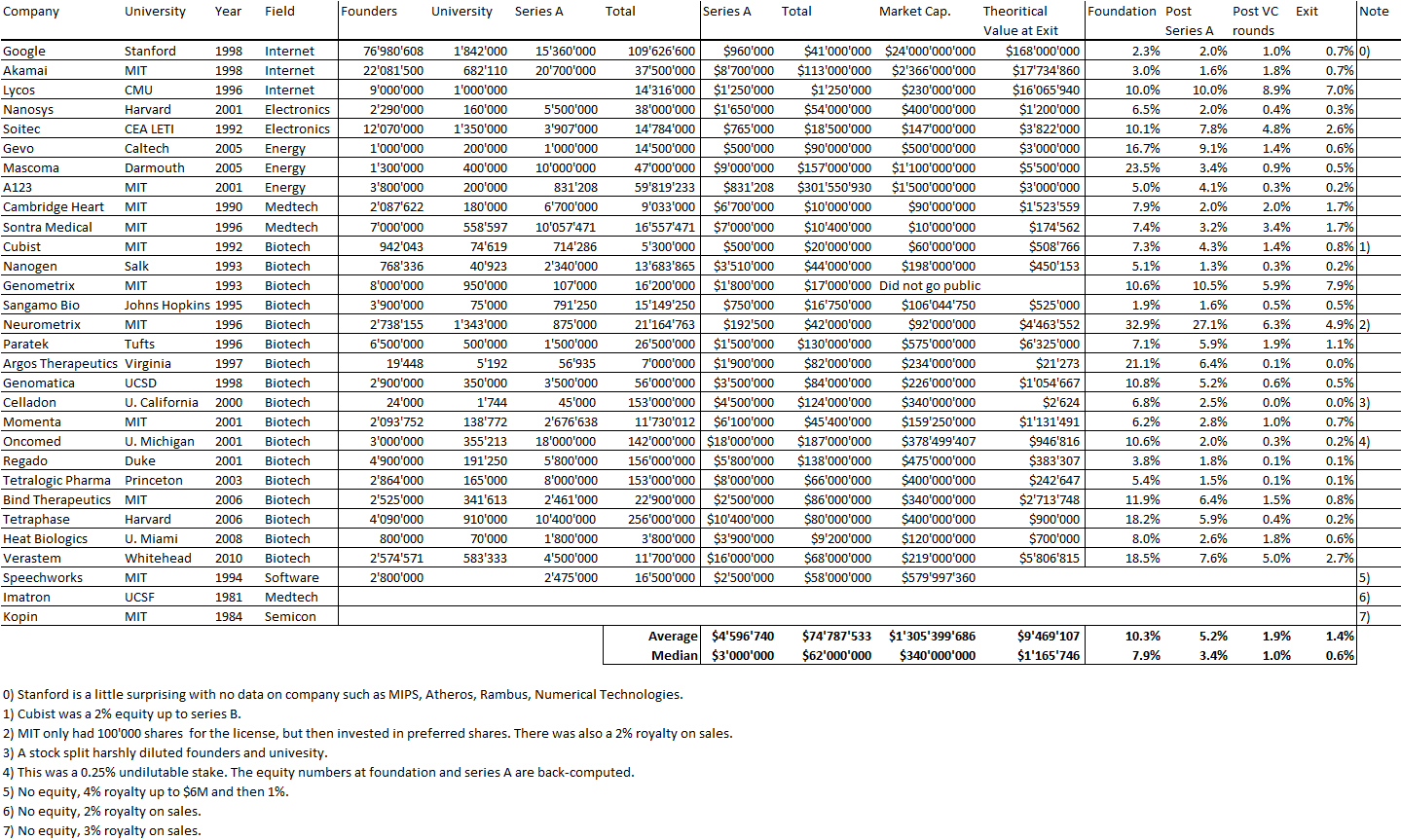

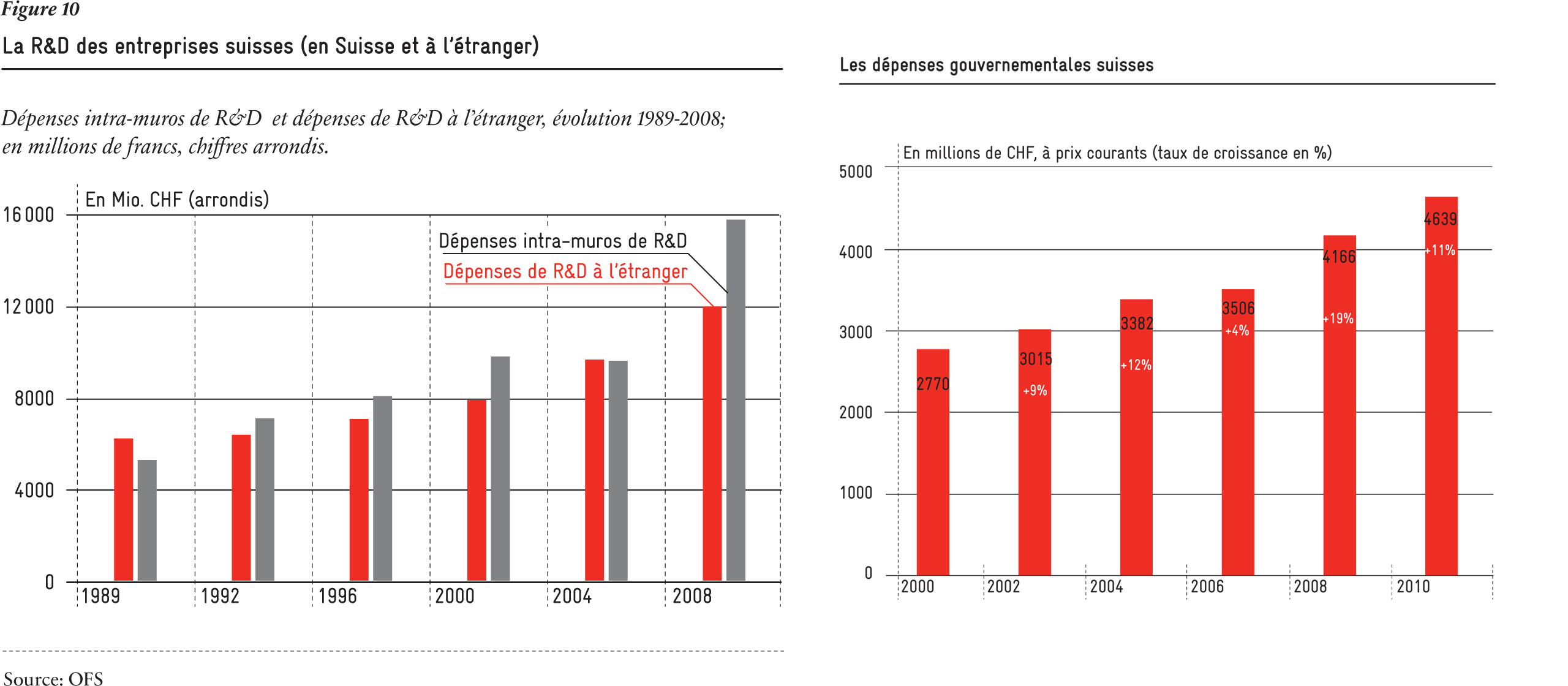

He begins by showing the strength of R&D from the private sector – 75 % of the 16 billion spent in Switzerland. He adds that Roche and Novartis in pharma represent a large portion of this amount (approximately 30% of all R&D spent in Switzerland) and they invest more abroad.

A first point of divergence, R&D is not innovation … In simple terms, innovation is the creation, closer to entrepreneurship than to R&D. Apple has always innovated and much better than other companies, but its R&D ratio is very low.

(Click on image to enlarge)

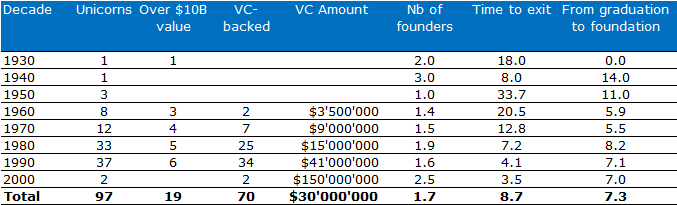

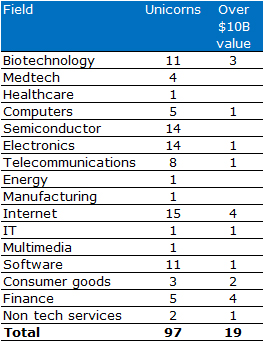

Then he compares Silicon Valley and Switzerland: “Silicon Valley massively encourages the emergence of new actors (start-ups) in the field of information technology and communication (ICT) while the Swiss model promotes rather large incumbents in the field of health.” [Page 20] and even [page 25] “Silicon Valley has deliberately chosen the new technologies of information and telecommunications (including the Internet) as the innovative axis of its development.” He concludes with: “You could say that Switzerland is for health what Silicon Valley is for ICT.”

Second point of divergence: Silicon Valley is not the Mecca of ICT, but that of high-tech entrepreneurship. Genentech and Chiron were the leaders of biotech before being bought by Roche and Novartis respectively. Intuitive Surgical is a leading medical technology company, Tesla Motors could become a major player in the automotive industry and there are hundreds of other start-ups in the fields of energy (massively financed by funds like Khosla or KP), in clean technology and health. Furthermore Silicon Valley has also large established companies such as HP and Intel which are no longer startups.

Comtesse is convinced that Switzerland is less fragile. “As amazing as it may seem, the Swiss model is more robust and efficient over the long term than Silicon Valley because it is less dependent on global rivalries and Silicon Valley may be under threat from Korea, China or any other part of the world. Switzerland is less so because the entry ticket in the field of health, namely the huge investment to develop higher education, university hospitals, research centers, the creation of companies producing blockbusters (products reaching the billion in sales) is so high that few regions can compete in this field.”

Third point of disagreement: I do see how Korea (through Samsung and LG) has indeed become a threat to Silicon Valley but I cannot see why it could not be in the field of health. Investments in electronics and telephony were also huge. Also, the higher and higher reluctance of emerging countries with intellectual property protection (patents) on drugs and the emergence of generics seem to me equally destabilizing.

Finally Comtesse also describes the weaknesses of innovation in Switzerland: “But the question that no politician really wanted to answer was the lack of good projects. If this question is asked the answer is obviously not the creation of science and technology parks, or even the transfer of technology, let alone coaching. It is the creativity that is lacking. How to make Switzerland and especially young people from higher education to be more creative?” Neil Rimer, from Index Ventures, said similar things: “There is innovation in Switzerland, but few entrepreneurs are ready to conquer the world” and “To attract [ … ] you need a critical mass of start-ups so that there are other options available in case of failure. […] Switzerland and its cantons seek to attract traditional companies or the administrative centers of large corporations. […] My biggest wish would be that the authorities encourage the creation of jobs creation in engineering, design, marketing and management. This is how we will attract a critical mass of professionals who create and grow start-ups in Switzerland.” (See L’innovation en Suisse d’après Neil Rimer).

There is a slight difference. Neil Rimer is not talking about good or bad projects, but about ambition. He even said on this blog a few months ago : “I continue to be amazed to hear that there is not enough support in Switzerland for ambitious projects. We and other European investors are perpetually in search of global projects from Switzerland. In my opinion, there are too many projects lacking ambition artificially supported by institutions – who also lack ambition- which gives the impression that there is enough entrepreneurial activity in Switzerland.”

Comtesse then returns to the role of government by distinguishing incremental innovation and disruptive innovation . “Indeed what matters to a nation is its overall innovation capacity including disruptive innovation. But if the State does not take all the risks, then nobody will do it. That is why it is urgent to give further instructions or guidelines to the CTI. Financing incremental innovation should not be its task, or only marginally.” [Page 27] “The Commission for Technology and Innovation (CTI) tends to support incremental innovation projects, which are less risky and easier to implement. These should be the prerogative of private companies and therefore should not benefit from government support. On the contrary, disruptive innovation, similarly to basic research, should be largely the responsibility of government.” [Page 30] “So on the one hand our innovation system is supported by large companies, and on the other hand by innovative SMEs as well, but those do not reach a sufficient critical mass to make often a difference. The idea would be not to finance individual projects as does CTI in general, but multi-partners programs led by one of the major Swiss companies.” [Page 28] “This approach does not preclude the emergence of new start-ups but these would be placed under the protective wing of medium and large Swiss companies. This would avoid start-ups to be immediately sold to the Americans (a phenomenon called “born to be sold”) or and help to counter the fact that they are never able to grow. It should be remembered that over 80 % of our start-ups do not perish in 7 years, while the “normal” rate is 50 % (one might well say that “never die” is another Swiss phenomenon).” [ Page 31]

I agree with him on the analysis, less on the implemention solutions. I find interesting the idea of giving priority of government support to disruptive innovation. It reminds me of the excellent analysis of Mariana Mazzucato about the Entrepreneurial State. I remain much more cautious about the idea of a consortium of major companies to develop and protect our start-ups. I understand the desire to reduce the risk of the sale, but I do not think the concept is realistic. Which real entrepreneur wants to be protected or controlled by a big even if nice brother… I also have some doubts about the ability and entrepreneurial desire of large corporations.

In a little artificial manner, Comtesse adds the idea of a tax incentives for innovation companies. “The Swiss tax system does not explicitly provide incentives for companies that conduct R&D. The simplest solution is the tax credit for innovation that would, in various ways, decease the burden of corporate tax based on their spending in innovation. Many large countries (the United States, Canada, England, Spain and France) have already implemented such an instrument. It is not, however, about encouraging any sector by this tool but rather to create an emulation for long-term innovation in the country. This device must provide to companies, especially SMEs, more freedom of maneuver to face the innovation process.” (See again Comtesse’s blog).

Here I can speak of complete disagreement. You can read again my analysis of Mazzucato denouncing tax optimization in this area. I never believed in tax incentives and I could be wrong. I understand the greater effectiveness of the approach, but I believe there are more perverse effects than real positive ones. Just look at the plight of the American Taxation system of the large technology companies.

Despite my criticism, this is an excellent report. Like all Contrarians, I focus more on disagreements but there are, in this analysis, extremely interesting points about the myths and realities of innovation in Switzerland. A short reminder as a way to end this post: Comtesse published a few months ago a Prezi presentation on the same topic, and you can read my comments about the Swiss model innovation : is it the best?